In November 2023, livestock farmer Leide Gerônimo sent a video to a WhatsApp group made up of residents of Portel, in the heartland of the Brazilian Amazonia state of Pará. It shows a person on the ground, covered in blood and motionless, being stabbed and their skin being ripped off. After a frightened reaction from the group, the video was deleted.

The message was sent during a time when the people living in the area’s two agroextractivist settlement communities – Acangatá and Alto Camarapi – were under extreme pressure. Gerônimo is being investigated by Pará’s government for landgrabbing in the Marajó Archipelago, where Portel is located.

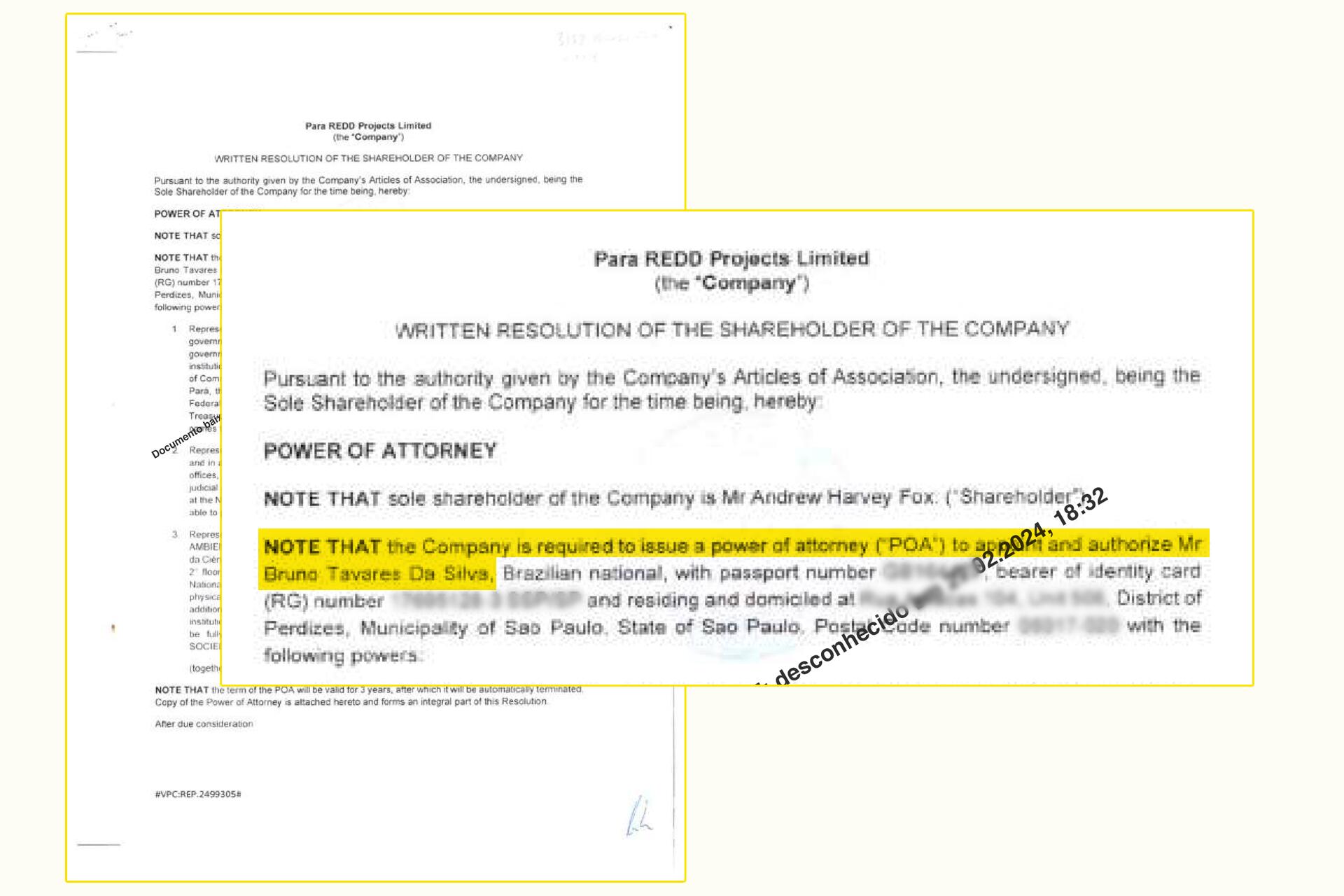

As if this were not enough, a former military police officer from São Paulo, who introduced himself as acting on behalf of investors in the United Arab Emirates, kept going in and out of these traditional territories. Bruno Tavares da Silva sought to assert these investors’ interests in the communities.

Also joining this story is a British executive – but not just any executive. Kevin Tremain is the son of a man who was convicted of one of England’s most infamous crimes, the theft of £ 26 million in gold and diamonds (or R$ 177.6 in today’s money), followed by the murder of a detective. And Tremain himself is also involved in a recent scandal in the Amazon.

What joins these three seemingly far-flung characters are carbon projects entered into with at least five rural communities inside of Pará’s Amazon.

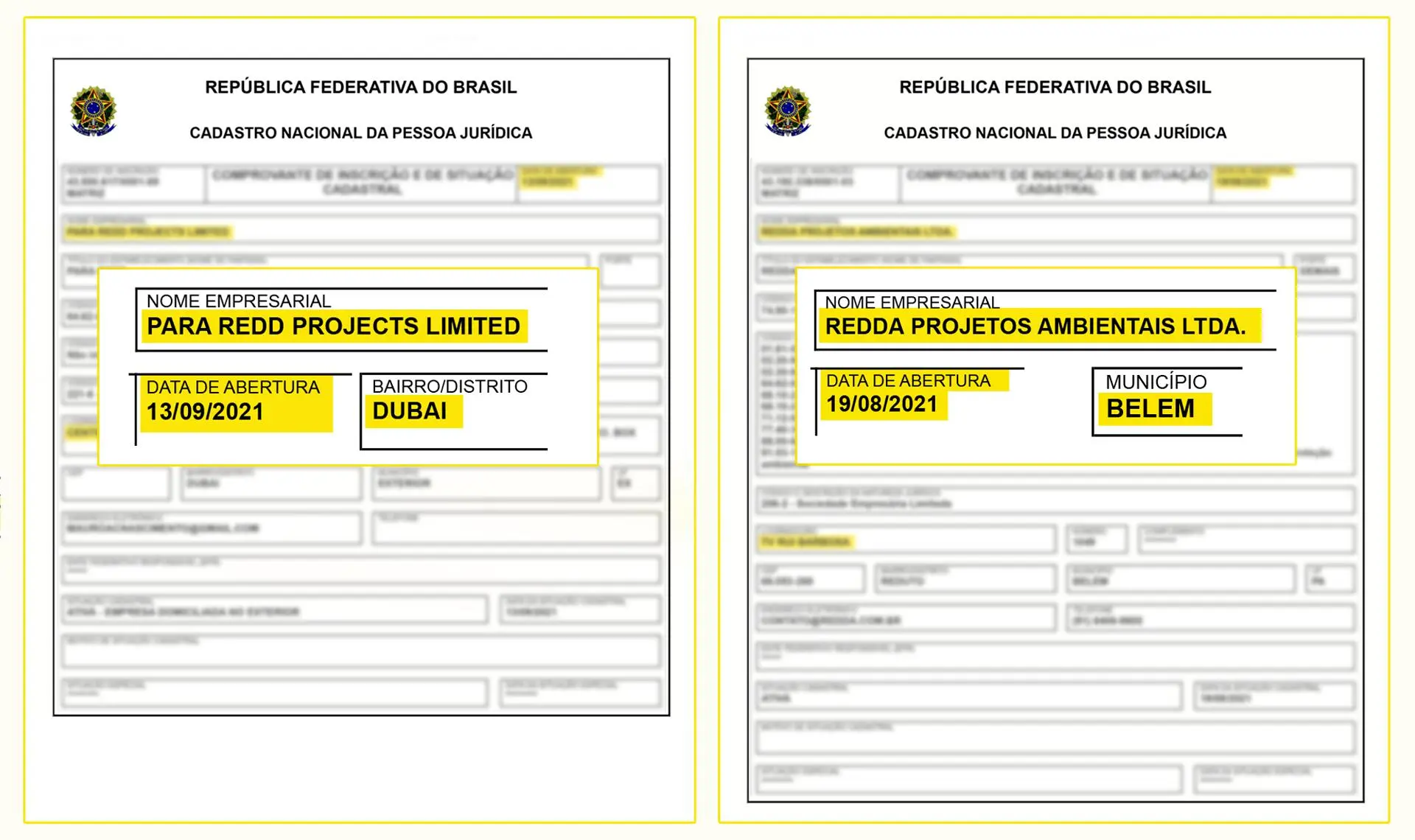

Since 2021, when the companies they are connected with, Pará Redd and Redda+, came to the communities and signed contracts with some of them, the story has produced at least seven lawsuits in Brazil’s courts, thousands of pages of documents, threats, and back-and-forth accusations. But no carbon credits.

Redda+ and Pará Redd are two separately registered companies, but in practice they work together and are connected to the same investors. They operate in the so-called voluntary carbon market, which is not subject to government regulation. In the Amazon, this market’s projects are based on a mechanism known as REDD+, which stands for Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation. The initial idea behind the mechanism, which originated in the United Nations, was to reimburse countries that preserve their forests and to use this tree-stored carbon — which ceases to be released into the atmosphere through deforestation or burning — as a credit to offset gas emissions in the countries that pollute the most. Yet it ended up moving to the private market, which sells credits to companies that want to offset their greenhouse gas emissions. In theory, a carbon credit can only be generated if the project proves it preserves the forest for longer – and therefore prevents more emissions from deforestation – than if the project did not exist.

Long-term contracts, uncertainty about payments, and the non-viability of traditional ways of life are the basic package of allegations that have reached the Public Prosecutor’s Office, the Public Defender’s Office, and agencies that promote traditional peoples’ rights in relation to this carbon rush in the Amazon. In this type of carbon deal prospecting, there is no lack of stories about contracts with abusive clauses. So far, there have been no reports of success on a project of this kind in collectively used territories, that is, on land not held by a single owner, such as extractivist reserves, agrarian settlements, territories belonging to the enslaved rebels known as Quilombolas, and Indigenous Territories. But cases involving Redda+ have drawn attention because of the actors involved and the degree of tension.

the marajó archipelago and communities under pressure. Infographic: Rodolfo Almeida/SUMAÚMA

Amazonian gold

The Redda+ website tells us the company operates “through a responsible and humane approach” with the complete carbon market cycle, “empowering people who care for the planet,” yet not one operational carbon project is shown.

The “Our team” section of the About Us page also fails to mention who works there. The Redda+ LinkedIn page says it is a business of between 50 and 200 employees, but only eight are connected to the profile – and none of them are the owner.

Officially, the carbon seller is a member of three bodies that could vouch for its reliability as a company: the UN Global Compact – Network Brazil, the Brazilian Coalition on Climate, Forests and Agriculture, and the NBS Brazil Alliance – a partnership of dozens of carbon companies operating in the country. On its website, the Alliance says that “the creation of guidelines and best practices to promote integrity in the sector is at the heart of the organization’s work.”

One relevant detail: when negotiations began, neither of these two companies had a corporate taxpayer ID number registered in Brazil. These numbers were only obtained right before contracts were signed with at least five associations in western Pará.

To understand how Marajó entered the carbon route, some historical context is needed. Just like in Portel, Gurupá, another municipality in the Marajó Archipelago, is part of a well-conserved area of the Amazon. Although it was occupied by Portuguese colonizers in the 17th century, and was part of attempts to explore the Amazon, no major economic cycle in the city was attached to deforestation. Nothing compared to the advancement of livestock and soybeans in the state’s east.

With a little luck, it takes twelve hours to travel by ferry along the Amazon River between Macapá (state of Amapá) and Gurupá. For residents of Belém, it’s twice as long. Upon arrival, you need to bounce down a dirt road by car for an hour until reaching the black waters of the Pucuruí River. Now it’s time to catch a motorboat to travel the last leg to Camutá do Pucuruí, the first community in Pará to be recognized at the state level as an extractivist settlement, in 2009. It sits inside of a state conservation area, where only government-authorized individuals may live and only sustainable activities can be developed by the communities.

The Camutá do Pucuruí Rural Workers’ Association is questioning certain terms of the contract signed with the United Arab Emirates company

None of this discouraged a carbon trading company, Pará Redd Projects Limited, which glimpsed a business opportunity in Marajó’s trees all the way from Dubai, in the United Arab Emirates. The confinement imposed by the pandemic also posed no hindrance to contact with the community’s residents.

“We had four meetings with them here,” says José Cândido Gomes da Silva, who goes by the name Mapará. He is the president of the Association of Rural Workers of Camutá do Pucuruí. The meetings took place between 2020 and 2021. “The biggest topic of discussion was the cost spreadsheet. But not the contract. We signed. When we went to look at it, a lot of things we’d asked to remove ended up appearing in the contract.”

During a trip to the area by motorboat, we pass by some homes belonging to Ribeirinhos, a traditional forest people, where children are playing in the water, and by a recently-burned area, punished by fire caused by a drought that hit the region last winter. We also cross paths with some grazing water buffaloes. Upon entering the water-soaked igarapé forest, the plants grow thicker, until we dock in a beautiful village.

It is the community of Nossa Senhora de Fátima, also within Gurupá’s municipal limits, where 34 families live on an area of 17,800 hectares. A woman holding an umbrella to shade herself from the sun draws near as a pressure cooker whistles in the background. The heat is intense and sunshine lights up the tidy houses, with their flowery gardens and grassy grounds. We are going to see the community’s cassava flour production facility, where the residents cheerfully peel cassava outside. Inside, others are roasting cassava in the oven.

Traditional communities in the municipality of Gurupá have been caring for the forest for years. Now, residents are being pressured by the carbon market

Inside the community center warehouse, a resident announces: “Carbon is the gold of the Amazon.” A phrase we hear repeated. The “gold” has finally reached these communities that have for centuries cared for the forest. In theory, the more preserved, the more valuable a place is to the companies that hold the negotiations between communities and the corporations that need to buy carbon because of legal requirements – not the case for companies headquartered in Brazil, where there is not yet a regulated carbon market – or, more frequently, for marketing reasons or because of shareholder pressure.

From 2020 to 2021, a few carbon companies came to the region’s villages. The directors of the Camutá do Pucuruí association thought Redda+ and Pará Redd proposal appeared the best.

We asked Mapará if Redda+ explained to them how, technically, a carbon market works. “No. To this day we’re trying to find out. We asked for a translation, because they said they had to fulfill an international standard. I didn’t know which standard it was. They needed to translate it so we could understand if it was true or not. This standard never appeared.”

Carbon credit companies, such as Redd Projects Limited and Redda, approached communities in Pará in 2020 and 2021

Sweet talk and arrogance

In parallel, the company was negotiating with communities in the neighboring municipality of Portel. The result was the Marajó Redd Project, the agreement for which was signed on October 23, 2021. The company’s plans were moving full-steam ahead.

Officially, the Marajó Redd Project was bold and ambitious. The conservation of 130,000 hectares would involve four traditional communities in Portel, preventing nearly 12 million metric tons in carbon emissions. There would be three extractivist communities – Alto Camarapi, Acangatá, and Ilha Grande do Pacajaí – and one Quilombola community – São Tomé Tauçú.

All of the project components were classified as gold-standard: climate, community, and biodiversity. If everything had run smoothly, it would have been Brazil’s largest project involving collective territories – covering an area larger than Pará’s state capital of Belém.

“They said it would make R$ 40 million to R$ 80 million [for the community] over 40 years,” shared someone from one of the communities that followed the project, asking to remain anonymous. “Except that over the course, after the contract was signed, they didn’t do everything they’d promised. They said how much [would be paid], but each month they cut the amount. It was cut in half. Then it was reduced even more.”

These amounts would correspond to an initial payment made while the project was being considered by the certifying body – an organization specialized in verifying whether the carbon project does in fact prevent greenhouse gas emissions – a period when it would still not be possible to issue and sell carbon credits. Two other people, in different locations, confirmed payments were reduced, which is also documented in messages exchanged between the investors – obtained by Joio through a court order, as we will see later.

The story we heard in Gurupá is similar. In this case, the contract was signed in late November 2021, and it is practically the same as the ones signed with the associations in Portel. Based on these contracts, Pará Redd is made the owner of 100% of the carbon credits – usually companies doing carbon projects keep a smaller percentage of credits than the land’s owners, whether they are individuals or a collective. The document does not state how the payment would be made. As the full owners of the credits, these companies could therefore double, triple, or quadruple sales without it resulting in any additional disbursements to residents.

In the case of Camutá do Pucuruí, in Gurupá, the document only says that Pará Redd “intends to make payments to the association, as a provider of environmental services, through the direct, monetary payment modality and, also, by providing social improvements to rural and urban communities.”

In addition, residents would not be responsible for executing resources; this would be the responsibility of Redda+, “considering the specific and most relevant needs of local communities.” Readjustment of payment amounts would depend on “community engagement.”

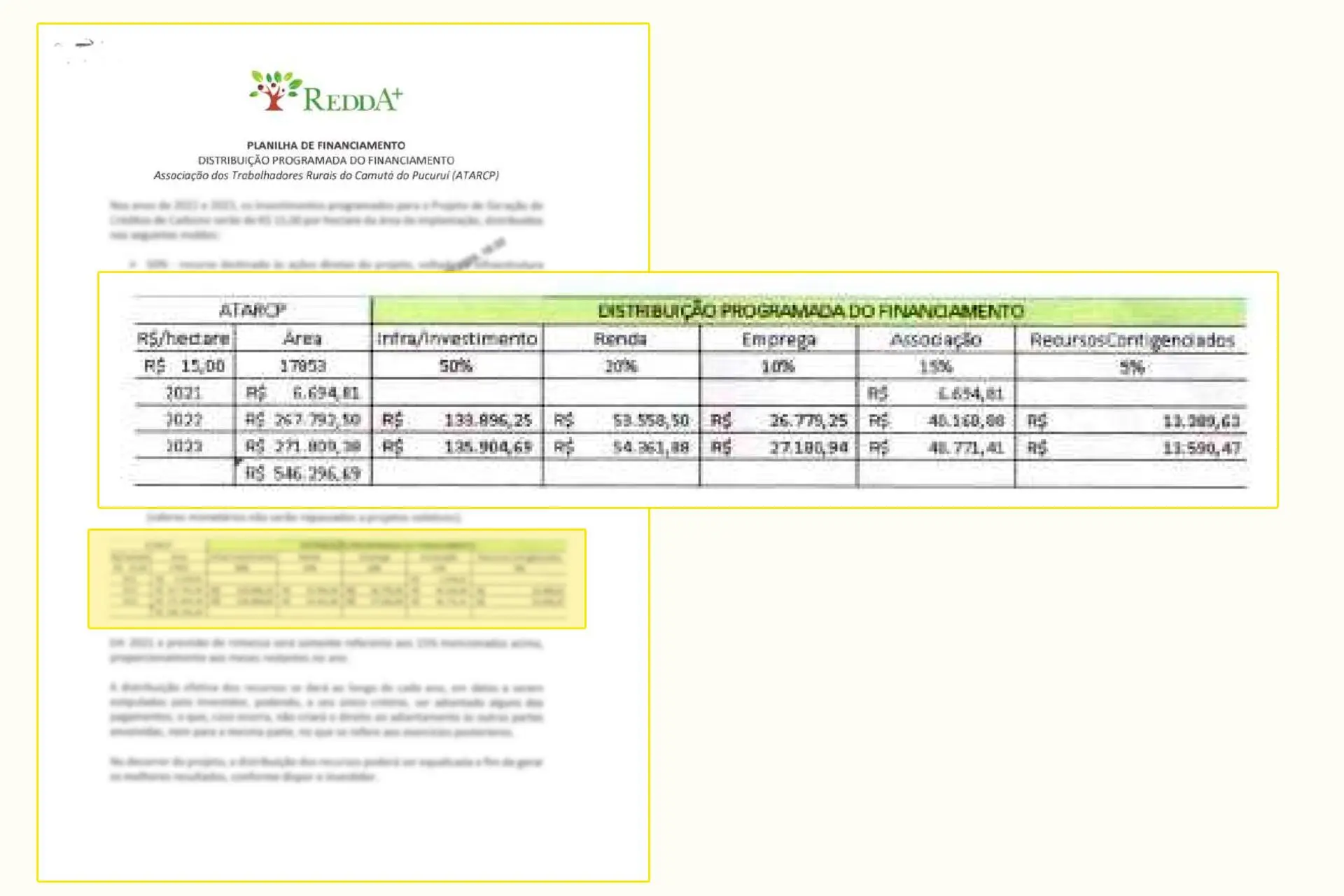

“They talked about paying a Redda Stipend,” says Antônio Gomes Pimentel, the secretary of the Camutá do Pucuruí association. “It was quite a low amount, really. Around US$ 31 a month. And when we went to look, they were the ones who would manage the resources.”

The attached document, which was included in a case before Pará’s courts, contains a spreadsheet with the payments that would be made in the first three years. Actually, the amount was much lower than Antônio reported: US$ 24 per family each month. There would also be a monthly investment of US$ 2,000 in the community, geared specifically toward improvements: building or refurbishing schools and hospitals and installing solar panels and artesian wells.

A spreadsheet containing the values that should be transferred to the community is attached to the ongoing judicial process in Pará

The same promise was made to communities in the municipality of Portel. We spoke to residents of Alto Camarapi and Acangatá, who preferred to remain anonymous for reasons of safety. They said an initial contact was made by Bruno Tavares da Silva, who introduced himself as the owner of Redda+ and began to personally visit the municipality’s various communities.

“He introduced himself by saying it was a very serious company that wanted to do carbon projects. It was the first time I’d heard about carbon credits and so I was a little suspicious,” says one person who followed the discussions.

The contract signed with the Alto Camarapi association stipulated that the companies could access any area in the territory, whenever and as much as they wanted to, for a 40-year period. Residents would be unable to sign contracts with organizations or companies without the consent of the party in charge of the carbon project. Furthermore, they gave up all rights to the project’s creation, development, and execution.

The contract with Gurupá also failed to define the rules for a territory use plan: “The basic principle of the partnership is forest conservation, as a physical and immaterial cultural asset, as protection against deforestation and illegal burns, as incentive for sustainable management and agroforestry, with alternative soil use, in a compensated manner,” the document describes.

The contracts we saw and the documents registered by Redda+ with the certifying body did not contain the boundaries of the area where the territory’s use would be frozen, nor did they clarify whether the residents could continue to use the land to extract timber, hunt, and farm. In an official letter dated April 2022, Redda+ reaffirmed its intention to issue credits for all 17,900 hectares of Camutá do Pucuruí, without explaining what the area’s use plan would be.

“It was there in the contract,” recalls Débora Coutinho Pimentel, a resident of Camutá do Pucuruí. “When they [the association’s directors] brought us the document to read, to explain what the situation was, it was already done. The damage was insane. So it was something that caught everyone very much by surprise.”

Débora Coutinho Pimentel, a Camutá resident, claims that the damage caused by the carbon project to the community was ‘insane’

The residents say the Redda+ representatives claimed to be investors from Dubai. “I didn’t take part in the early meetings, but after a while I started to participate. The company’s representative wouldn’t let us speak. He would talk louder, with a kind of arrogance. And we started to get suspicious,” says Selma França Marques, a resident of Camutá do Pucuruí.

The company’s representative was former military police officer Bruno Tavares. Sources we spoke to in Portel and in Gurupá also commonly reported a change in relations after signing the contract. He was no longer as easy to reach. And pressure from the company ramped up.

“They just completely disappeared. We were getting suspicious, we hired a lawyer, we went to look at it and the mistakes were right there,” Débora explains. “They come with that sweet talk. They knew we didn’t have a lot of wealth, so they wanted to trick us. So they say marvelously good things. And then people fall for their sweet talk.”

Mapará, the president of the association in Camutá, says they were concerned about the contract’s contents and took a motorboat to Gurupá before traveling 24 hours by boat to Belém, where Bruno has a Redda+ office. “But he gave us a pretty shabby welcome,” he recalls. Asked to comment, Bruno did not respond to our questions.

From timber to air

At the turn of the twenty-first century, after being driven out several times by these same residents, timber companies began to sign legal timber management contracts in Gurupá. The term on some had ended right before the carbon companies arrived.

“Timber provided stability in the community’s life,” says Gilberto Gomes da Silva, a former president of the association of Camutá do Pucuruí. “It’s true we had losses, because each person is paid and does what they can do. But we kept making improvements. House, power, internet.”

If there is one aspect on which there is no consensus, it is the timber project’s legacy. According to residents, four extraction phases were authorized. Débora says she was against the project being constantly renewed. “I think it was a good thing, because a lot of people built things with this project. But it’s harmful to Nature. And now, we’re feeling the impact: the low water levels, the dryness. I think a lot about the environment,” she says.

“I want to leave it for my child. What we have today is what the ancestors left for us to enjoy. If they had agreed to let a company come in here, do you think we’d have what we have today?”

Coming out of a cycle of logging, getting paid for the forest that was left standing seemed like a great idea. “We expected as much money as from timber,” says Antônio Pimentel, the association’s secretary. Several residents reported that families were usually paid between US$ 370 to US$ 550 per month for timber extraction.

Bruno Tavares, a former PM and Redda+ representative in Portel and Gurupá, stopped returning calls after signing the contract, according to residents. Photo: Personal archive

Police officers and livestock farmers

It was timber that led Portel’s Marajó Redd Project to unravel. The Alto Camarapi association’s title was recognized in 2019, and it then filed a request with the Pará state government’s Office of the Environment and Sustainability Secretary so that it could legally extract timber.

“We asked Redda+ about this. Could the carbon credit project make it so that we are no longer running management? They said no, that the methodology they were proposing wouldn’t have an impact, it was different. That was why we thought it was a good proposal. That life would only get better,” said one resident, asking to remain anonymous.

Yet that was when the associations found the company had introduced a new methodology that forced them to get rid of their forestry management projects, without consulting them. However, things were to grow even worse. According to this same resident, in September 2023, they called the community to sign a document to change the methodology. “Anyone with [a management plan] would have to cancel [it]. They couldn’t plant any crops. They couldn’t do subsistence farming. It would directly interfere with our way of life. We did not agree.”

Tensions rose until, two months later, Leide Gerônimo sent the threatening video over WhatsApp. Two days later, Wilton and Weldes Gerônimo, his sons, attended meetings in Alto Camarapi with representatives from Redda+. In fact, the meeting took place without authorization from the residents’ association.

Yet why would people suspected of landgrabbing and the carbon company’s employees be holding a meeting? Redda+ wanted support from community members after the associations had filed suit with the state courts asking for the carbon contract to be voided. And the Gerônimo family is constantly clashing with the association in Alto Camarapi, since they raise cattle in a prohibited area, according to enforcement actions by the state of Pará. It was a meeting of interests between people who publicly promote the Amazon’s conservation and people who destroy it.

At the time, with around 20 community members in attendance, one of the Redda+ employees, Reginaldo Lima, said: “No president has the power to remove us [the company] from here [the territories],” he said in reference to the association’s president, Francisco Rodrigues de Melo. He says this in a video we had access to.

The associations say the discussion should have been held collectively, but Redda+ had insisted on maintaining the methodology and on taking part in the community’s internal meetings. That was when the residents decided to suspend partnership activities.

The company’s aggressiveness led two of the four associations, in Alto Camarapi and Acangatá, to try to get out of the contract. “Residents began to experience daily threats. Members and the board started to receive threats inside and outside of the territories, since there were already conflicts and pressure to deforest areas,” attorney Guilherme Sobral writes in a suit brought by the association of Alto Camarapi asking for Redda+ representatives to be blocked from entering the extractivist reserve.

In the petition, Sobral affirms that, instead of protecting Nature in partnership with the communities, the company became “another agent of violence,” promoting “true chaos within the territories.” According to the document: “After the association turned down the contract, the company began to importune, intimidate, and threaten association leaders and workers, to agree to their illegalities and acts of violation of territorial rights and self-governance.” Bruno Tavares, of Redda+, did not answer reporter requests for an interview and for comment.

From security guard to carbon trader

All that was left was to understand who Bruno Tavares da Silva is and if he has a history of working in the environmental area. He does not. Born in 1981, when he was 40 years old, Bruno left the ranks of the Military Police of São Paulo, having reached the rank of captain.

This happened a few weeks after contracts were signed in Portel and Gurupá and four months after Redda+ received a corporate taxpayer ID number. In parallel, corporate taxpayer ID numbers were applied for and received by Pará Redd and a third company, Tav Company Participações Sociedade Unipessoal Ltda, headquartered at Avenida Paulista in São Paulo, which would later be included as a party to the contracts signed with the communities.

There is also a fourth company registered in Bruno’s name. ETS Gerenciamento de Risco Ltda was opened one year earlier and it seemed suspicious to us. The company is connected to a risk management firm headquartered in the United Kingdom and lists as a partner Darren John Aldrich, whose Linkedin profile says he is a former member of the British Armed Forces who is proud of “his 19 years of clandestine and international experience” as an explanation of how a “pragmatic approach” is guaranteed.

Yet this still didn’t explain everything. On October 26, 2021, British executive Naro Nesta Zimmerman signed a power of attorney empowering the Brazilian Bruno to legally represent Redda+. At the time it was signed, Zimmerman was the head of Private Client Services for the JTC Group, a fiduciary industry corporation, or rather, a company specializing in financial asset management.

He also shows up as a representative of Pará Redd in the contract with one of the associations involved in the Marajó Redd Project.

There is no mention in JTC Group financial reports of any company operations in the carbon market, and in recent years, no money was even transacted in Brazil.

Asked for comment, Naro Zimmerman responded by e-mail. “I’d like to clarify that the contract you mentioned earlier was terminated by mutual agreement in June 2023. As a result, no REDD+ project has been initiated in that particular area. We will be making no further comment and reserve all rights,” he said, without clarifying on whose behalf he was speaking.

The Finance Ministry lists Pará Redd and TAV Company as partners in Redda+. Both companies have Bruno as a partner.

Over a few days, we searched for the thread that would lead us to the real owners. The trail began to grow warmer while reading through a lawsuit brought in the Pará state courts. In one of the attached documents, the sole owner of Pará Redd is listed as Andrew Harvey Fox. In Mauritius, where the document granting Bruno power of attorney was signed, Fox is listed as owning eleven companies – none of which are Redda+.

In a document attached to the lawsuit filed in Pará, Andrew Harvey Fox is listed as the sole owner of Pará Redd

A few weeks went by until a new needle turned up in the haystack. A labor suit filed in Pará, which we had found in a bundle of documents, left no question as to who the real owners of Redda+ and Pará Redd were.

If Bruno Tavares had not quarreled with a trusted employee, he would perhaps continue to publicly figure as the sole owner of companies that say very little.

Two sources confirmed that in 2020, Bruno had worked security for English businessman Kevin Tremain, at Avoided Deforestation Project (Manaus) Limited, ADPML, a company headquartered on the British isle of Guernsey.

At 10:35 on September 25, 2023, Kevin Tremain sent an e-mail filled with bad news to Bruno, the supposed owner of Redda+: “Due to the unstable situation and concerns raised, I am forced to take measures to protect my interests and investments (…). We would like to inform you that we’ve sent US$ 400,000 for expenses through the end of 2023, but we will only send US$ 150,000 to Redda+ for expenses.” This was when the communities saw their funds dwindle.

Tremain was worried about the news this former trusted employee had brought to him. He had reported endless problems to investors: communities threatened by Redda+, carbon projects that failed to start, Bruno’s aggressive actions with representatives from traditional peoples’ associations. Two other partners were included in copy in the e-mail attached to the lawsuit to which we had access: Andrew Harvey Fox and Tahsin Choudhury. Choudhury is the owner of NET Zero Sustainability Limited, another carbon company, which opened in 2020.

A cinematic English crime

While dealing internally with the problems involving Bruno, Kevin Tremain got an even bigger headache. On October 3, 2023, the Brazilian press reported that Pará’s Office of the Public Defender had filed suit against four companies working with carbon projects in Portel. Tremain’s ADPML was one of them.

The charges suggest a classic case of “carbon landgrabbing”: the companies would issue credits by taking advantage of smallholder lands registered with the Environmental Registry of Rural Properties. The list of credit buyers shows the size of the problem that has opened up around carbon markets: Boeing, Delta Airlines, Air France, Amazon, Repsol, Samsung, Toshiba, Kingston, and England’s Liverpool Football Club.

One of the companies responsible for the projects was ADPML, renamed as Amazon Forest People. The suggestive name hid the fact that the company is located in Essex, England, and is owned by Tremain. Three weeks later, British newspaper The Mirror broke the news that the company’s registered address is used as a residence by Tremain’s father, Kenneth Noye.

This wouldn’t be a big deal, except that Noye was one of the participants in one of the United Kingdom’s biggest robberies. The so-called Brinks-Mat Robbery took place in November 1983. At the time, £ 26 million in gold and diamonds were stolen from a safe in a warehouse near Heathrow Airport in London. Over the course of the investigation, Noye killed a detective. He was convicted at trial.

Questioned by The Mirror, Tremain said he is just a consultant and claimed his father is in no way related to the carbon project. He said he did not know who the company’s actual owners were, but the records we obtained show he is the owner. A story on Amazon Forest People lists Andrew Harvey Fox as the company’s representative.

“When the reports came out, we could see they were the same group,” says one member of the traditional Ribeirinho community who was involved in negotiations on the Marajó Redd Project. “We fell into a trap. They just changed the name of the company. That was when we understood that they are the real owners of Redda+.”

Among military police and relatives

“The communities think Redda+ intimidates them and that it has Federal Police support,” Fox wrote in an e-mail sent to Bruno on October 16, 2023. At that point, association representatives were staying in touch, without Bruno’s intervention, with the carbon projects’ real investors.

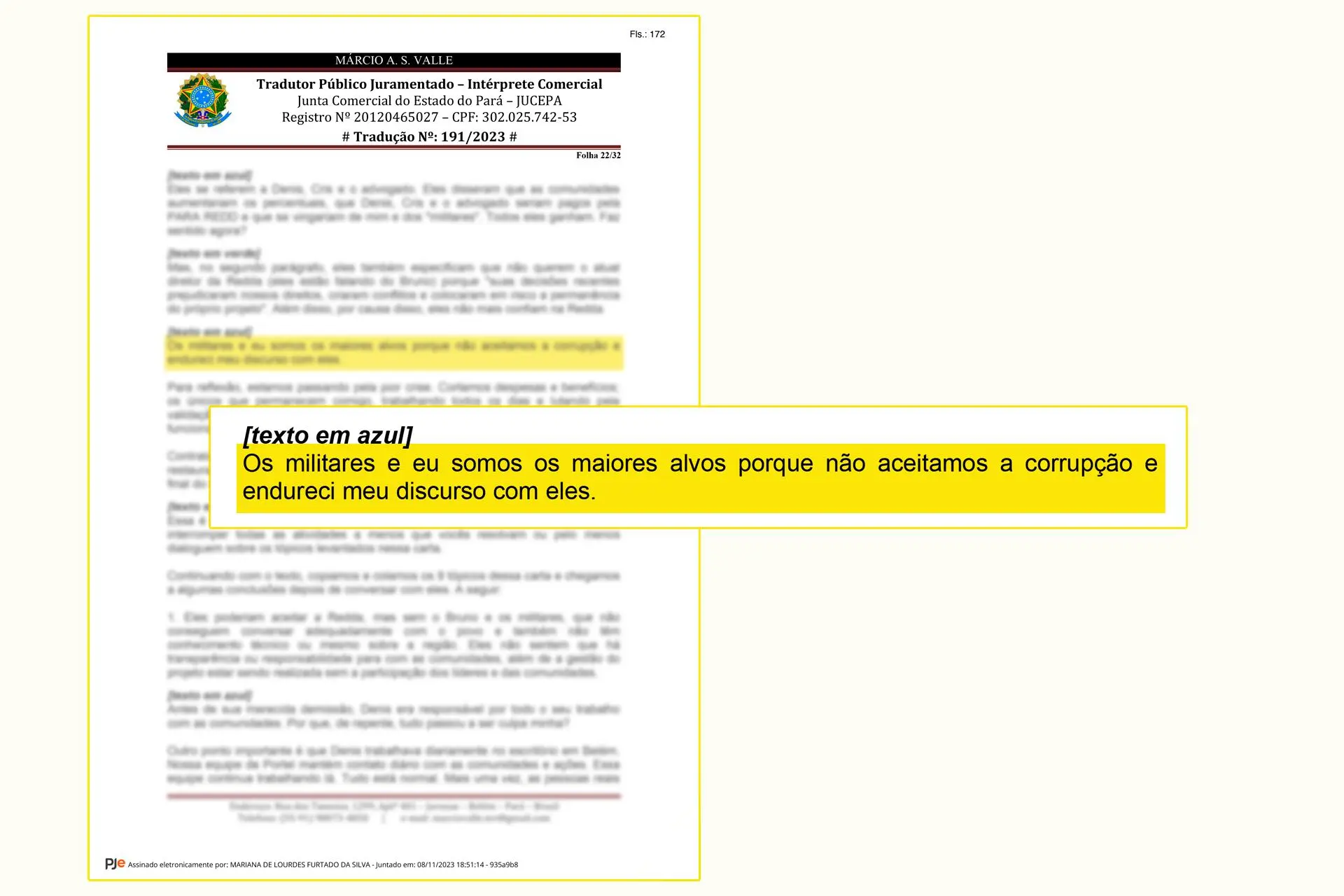

Bruno answered a few hours later: “We’ve had a former police officer who worked in Portel since we started. They [the Redda+ employees] went to (name redacted for protection)’s house to talk, as we normally do. Now, they’re saying this is ‘intimidation,’ but it’s not true.”

“The military [police] officers and I are the biggest targets, because we don’t accept corruption and I’ve hardened my discourse with them [the community members],” Bruno says in his own defense, in October 2023, after being questioned by investors. “Reflecting, we’re going through the worst crisis. We’ve cut expenses and benefits; the only people still with me, working every day and fighting for validation and against lies are the people here today. Relatives, military [police] officers or employees are all capable and honest.”

Among the company’s employees were other members of the military police force, such as Reginaldo Lima, Bruno’s brother Tiago Tavares da Silva, and his wife, Giovana Latorre Tavares. The latter two, assigned to the São Paulo Military Police’s Firefighting Company, each asked to take a one-year leave in August 2022 to deal with private matters.

When asked by the investors about relations with the community, Bruno Tavares replied that he didn’t accept corruption

Illegalities

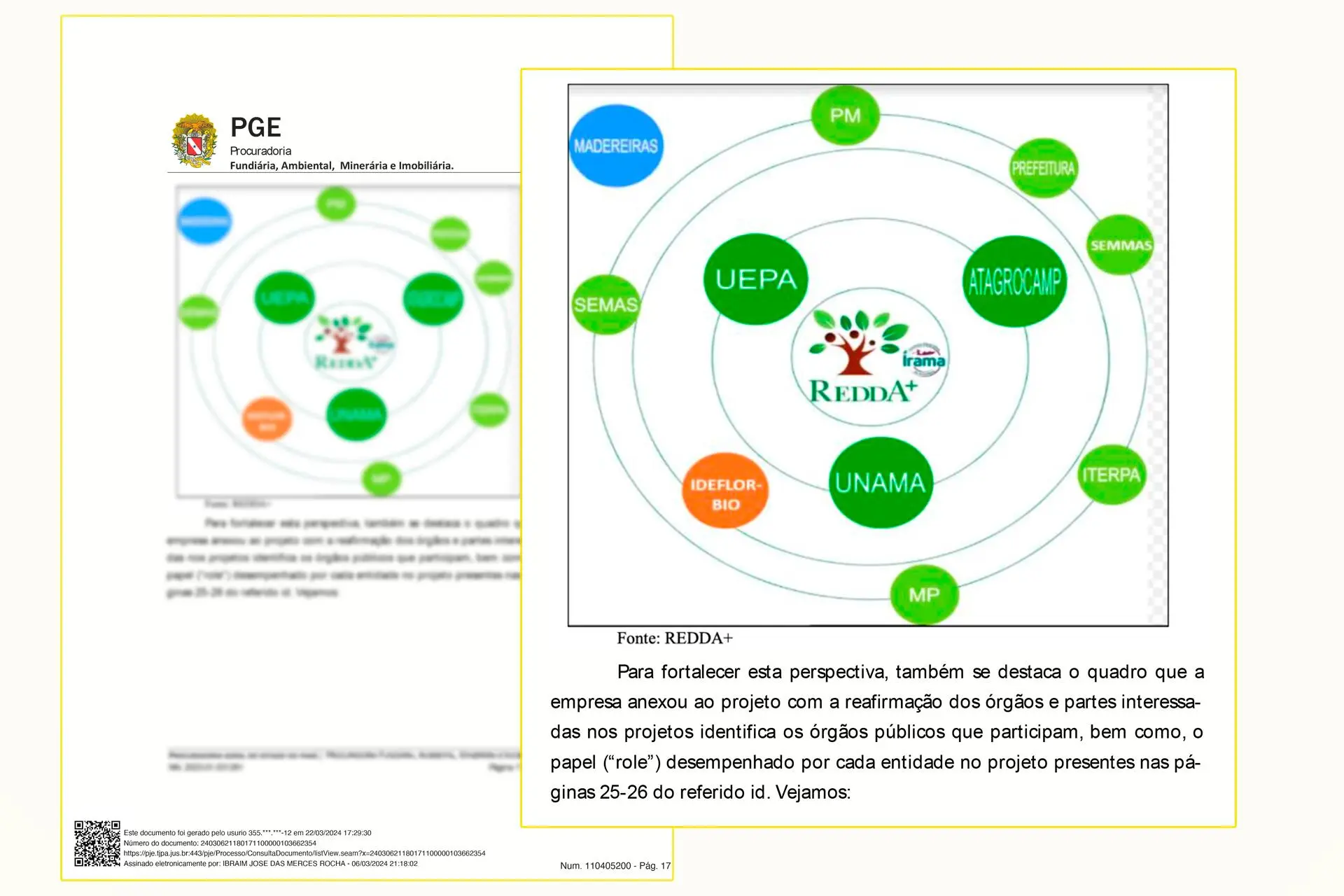

On March 6, 2024, the Prosecutor General of the State of Pará filed a lawsuit asking that contracts signed with Redda+ under the auspices of the Marajó Redd Project be voided. Then-prosecutor Ibraim José das Mercês Rocha understood that the company promoted an attempt to irregularly take ownership by operating on public lands without the consent of the agencies responsible. Worse still: it feigned consent from these agencies – the Pará Land Institute (Iterpa), the Office of the State Environment Secretary, and the Institute of Forest Development and Biodiversity (Ideflor-Bio).

“It is worth noting that this case is one where an exemplary punishment should be handed down,” Rocha writes. He points out that it is easy to understand that the law was violated.

In a document filed with the certification body, Redda+ said it has approval from these public agencies, but at least one of them, the Pará State Institute of Forest Development and Biodiversity, denied, in a document sent to the Prosecutor General’s Office on December 17, 2023, ever being consulted. The Prosecutor’s Office is asking the courts to void the contract signed with two of the four associations and for the state to be paid R$ 4.4 million for property damage and nonpecuniary damages.

Redda+ informed the Pará Public Prosecutor’s Office that it has the consent of public bodies and that it operates in the state in a regular and legal manner

In the prosecutor’s view, even if it is a private contract, the fact that it was executed in relation to public land requires the consultation and involvement of state agencies.

“Therefore, not only does this concern an area that is not private property, but rather is publicly-owned, as well as the agencies responsible not being consulted, and although traditional communities are not necessarily subject to the bidding process to obtain a concession on state public forests, obviously they can only explore and contract in relation to what they were effectively and expressly guaranteed, which is not the case of carbon credit transactions.”

This suit was thrown out because the judge assigned the case understood that the associations should file as plaintiffs instead of the prosecutor.

History repeats itself

The residents of Camutá do Pucuruí even had some “luck.” They were initially in talks with the company to try to get out of the contract. In an official letter sent to the association’s lawyers in April 2022, Redda+ refused to revisit its methods for calculating payments and claimed that it will moreover incur losses from the project in Gurupá if it agrees to allocate 40% for the association, as requested.

“Because Redda+ has an exact cost calculation system, the percentage set in relation to the net earnings from carbon credit sales is much higher than any competitor. And, based on an awareness of this system for capturing resources and presenting results, Redda+ created a proposal, which resulted in the contract signed with the association,” the document reads. According to the company, the project would transact around US$ 1,6 million annually.

As negotiations were unsuccessful, on March 21, 2023, the association appealed to Pará’s courts. “The error is unmistakably there due to the fact that the defendant has taken advantage of a lack, by the plaintiff and its associates, of technical and specific knowledge of the details of the business, so as to insert clearly abusive and unfair clauses into an actual standard contract that was neither negotiated nor discussed, but rather unilaterally imposed,” argues the initial filing, made by attorney Ismael Moraes.

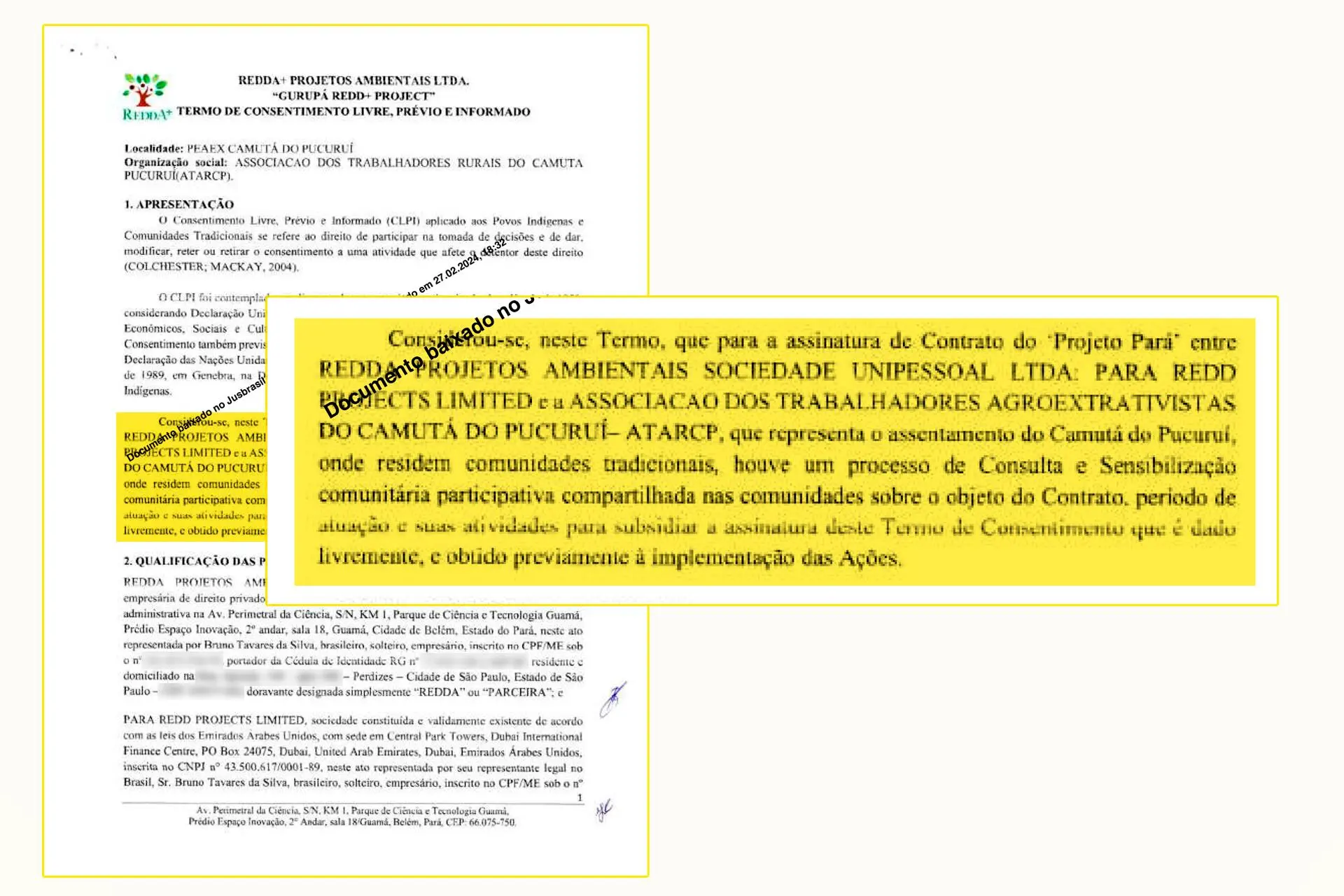

By law, projects in territories that are used collectively in Brazil must be submitted to a prior consultation protocol, as established by the International Labour Organization. In this project, what the company calls a consultation document is, in fact, an official letter signed by the two parties, as if Redda+ were also a participant in this step.

“The settlement does not have its own consultation protocol,” the company argues. “Therefore, Redda+, in common agreement with the interested parties, organized a consultation of the communities along with leaders and the involvement of partners” – the company mentions the Pará State Institute of Forest Development and Biodiversity and the State University of Pará. Although external organizations participated, the consultation excluded the agency legally responsible for the agrarian settlements, the Pará Land Institute (Iterpa).

Projetos em terras de uso coletivo exigem consulta prévia conforme protocolo da OIT, mas a Redda+ só apresentou um ofício assinado pelas duas partes

Regarding Camutá do Pucuruí, the courts decided to revoke the contract on July 12, 2023. Yet anyone who thinks this spells the end of carbon prospecting would be mistaken.

Mapará, the association’s current president, smiles while saying that entering into another carbon contract is inevitable. “Today, we’re free in the market. Because of everything that happened, we’re studying the right way to do it. We’ve already had other companies come to us.”

Bruno Tavares, Kevin Tremain, Andrew Harvey Fox, and Tahsin Choudhury were all asked for comment by e-mail and WhatsApp message. Tavares, Tremain, and Fox did not respond.

By e-mail, Tahsin Choudhury denied being one of the owners of Redda+. “You are mistaken in that I am not an owner of REDDA and therefore your questions are no longer relevant in that context,” he wrote. We sent him messages that were exchanged among the company’s investors, including Tahsin himself. He provided no further response.

We asked Leide Gerônimo and his sons, Weldes and Wilton, for comment. They did not respond.

We also contacted the UN Global Compact – Network Brazil, the Brazilian Coalition on Climate, Forests and Agriculture, and the NBS Brazil Alliance. Their responses may be read in full here.

The Brazilian Coalition on Climate, Forests and Agriculture said it was not made aware of reports about the Redda+ company through formal channels. “We are going to assess the case and bring it to internal authorities to decide on the procedure to adopt and an adequate response. It is worth noting that, in their Statement of Adhesion to the movement, Coalition members undertake a commitment to operate ‘within the ethical parameters required by Brazilian society,'” the company said through its press agent.

While the NBS Brazil Alliance wrote that “The promotion of good practices and integrity is at the core of our action and we take the reports emerging in both the industry and in relation to Alliance members seriously. We will try to look into and understand the case. Moreover, our Ethics Committee can act if there is cause.”

In its response, the UN Global Compact – Network Brazil said: “We are firmly against any action that violates the principles of Human Rights, Labor, Environment, and Anti-Corruption. In light of recent information of reports about the Redda+ company, which we learned about through the press, the UN Global Compact – Network Brazil has begun to discuss the case within the initiative’s competent authorities and has triggered the integrity measures established in its rules.”

This report was done by the team at news outlet O Joio e O Trigo, investigating food, health, and power and is republished here in partnership with SUMAÚMA.

Em julho de 2023, decisão judicial revogou o contrato de projeto de carbono d Camutá do Pucuruí, mas as pressões neste mercado de carbono ainda persistem

Text y photos: João Peres and Tatiana Merlino (O Joio e O Trigo)

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Spanish translation: Denise Bobadilha

English translation: Meritxell Almarza

Photo editor: Lela Beltrão

Page setup and finishing: Natália Chagas

Editorial workflow coordination: Viviane Zandonadi

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum