Every two weeks, nurse Clara Opoxina spends at least seven days inside the Yanomami Indigenous Territory, where around 10,000 Indigenous people live in a vast highland region of Roraima state that has been devastated by an invasion of illegal miners. Clara, as she is called, travels with the teams she coordinates to territory villages, where they collect fingerstick blood samples from every resident to test for malaria, medicate the ill, and airlift out those in critical condition. The teams are also working to reestablish primary care by providing vaccinations, controlling worms and treating malnutrition.

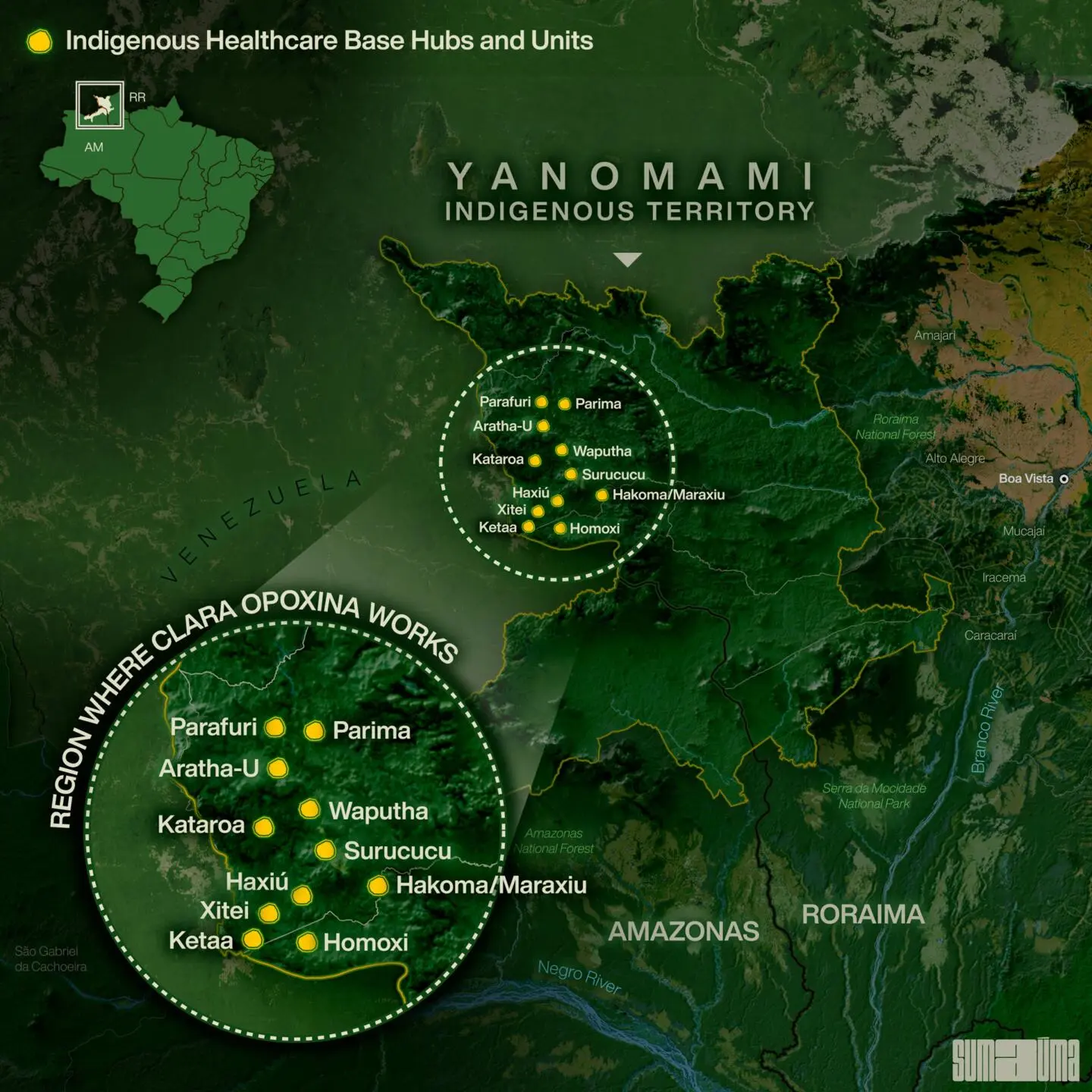

This has been Clara’s life since early last year, when the administration of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva declared a public health emergency in Brazil’s largest Indigenous territory, which covers more than 37,000 square miles and has an estimated population of 31,000. Some of the communities she has visited hadn’t received any healthcare teams for over two years. She also helped reopen four of the seven healthcare units called base hubs that had been abandoned or closed as a result of the invasion of illegal gold miners under the administration of far-right president Jair Bolsonaro. The territory has 37 hubs, and at least one remains closed.

Despite these emergency actions, 363 Yanomami from the Indigenous territory died in 2023 on or off their own land (many had to be airlifted to outside hospitals), as announced by the Ministry of Health on February 22. This figure is 6% higher than the 343 deaths recorded in 2022, the last year of the Bolsonaro administration, which encouraged wildcat mining and filled management posts at Special Indigenous Public Health Districts with its own people. The Lula administration argues that deaths were underreported during the previous government, and Clara herself is still trying to document deaths in recent years. Whatever the precise figure, these victims represent a shocking 1% of the population living on Yanomami lands. In earlier reports published by SUMAÚMA, people working in the region blamed the situation on mismanagement and the failure of the Armed Forces to cooperate with efforts to remove the miners.

Clara takes part in a helicopter operation to rescue patients in Haxiú in June 2023 and examines a child in Wathou in March 2024. Photos: personal archives

Clara has been working in the Yanomami Special Indigenous Public Health District for 12 years now. She is an outsourced employee, like everyone in these public health districts. The nurse chooses her words carefully but leaves it clear that the genocide of this people—who have faced intermittent waves of extermination since their first encounters with the napëpë (non-Indigenous) in the last century—will not end until every last illegal miner is expelled. Malaria is not endemic in the highlands of Roraima, within Yanomami territory; rather, the disease was brought in by the illicit miners, estimated to number 20,000 under the Bolsonaro administration.

Worse yet, the craters they dig in their search for gold and cassiterite and the equipment they haul in—dredges, gas cans, stoves—form receptacles for standing water that then become breeding grounds for mosquitoes of the genus Anopheles, whose female is the vector of malaria-causing parasites of the genus Plasmodium. If the miners keep on returning after they’ve been driven out—as happened in the second half of last year and Clara says she saw “with [her] own eyes”—it will be impossible to eliminate the mosquito breeding grounds.

A native of Barbacena, Minas Gerais state, Clara moved to the Amazon right after she graduated college. She is one of the few people in the Yanomami Public Health District who speaks Yanomam, one of the six local languages. When the Yanomami saw how fascinated she was by the necklaces of armadillo tails children wear as amulets, they gave her the name Opoxina, which means armadillo tail. She now wears a necklace with a bigger tail, from a giant armadillo. Clara has caught malaria twice. In fact, she was sick when she gave birth to her older daughter, now eight; her younger child is five.

INFOGRAPHIC: RODOLFO ALMEIDA

INFOGRAPHIC: RODOLFO ALMEIDA

Below are the main excerpts from the interview with Clara held in Rio de Janeiro in February 2024.

SUMAÚMA: What has your work life been like?

CLARA OPOXINA: I’m based in São Gabriel da Cachoeira, which is at the tip of Yanomami territory, in the state of Amazonas, and every two weeks I travel through Yanomami lands. In the region of São Gabriel, a logistics team from the DSEI [Special Indigenous Public Health District] takes medication and providers in every two weeks. It’s a three-hour flight to Boa Vista, capital of Roraima state, in a cargo plane that fits ten, copilot included. In Roraima, I have to arrange things, weigh everything. I usually enter [the territory] the next day. It’s a one-hour, 40-minute flight in a single-engine plane to the base hub in Surucucu. There, I coordinate a region that covers ten base hubs serving nearly 10,000 Yanomami. Last year I spent until September reopening regional posts that had been closed when miners were there. By October we had managed to reopen them, and I began coordinating missions to the more remote villages that weren’t receiving care.

After the government declared an emergency in the territory, it was hoped that the health situation would improve more quickly. But it’s still dramatic in some places.

In some places, yes, because there’s a lot of malaria. By the middle of the year the miners had been driven out but then, as the media showed, they began returning and this had a negative impact again. The situation is very complex; we need a lot of teams to be in a lot of places. And malaria is a dynamic disease. If a Yanomami with malaria goes to another community where they don’t have the disease, then that community will start having cases, so we have to keep going to all these hotspots. In addition to our rescue missions, we try to get there to provide health care.

What exactly do you do during a rescue operation?

In this region, we get there by helicopter. We perform rescue operations every day. In some places the Yanomami have radios; they advise us who is critically ill, how many people there are. Sometimes they use the miners’ Internet if they can get a signal, which is much less the case now. Sometimes they’ll walk a whole day to reach a community that has a radio. There are various ways these calls reach us, but it happens every day. The distances are enormous. Sometimes the community is a three-day walk from the nearest post. In Surucucu, there are no boats; it’s a mountainous region. Farther north there’s the Parima River, which is navigable; there’s another river in the Parafuri area. But in most of this region, the Yanomami walk a lot. Before they had malaria, they’d go to the post; a day’s walk is easy for them. But now with malaria, it’s a very delicate situation, because they’re debilitated.

If one person in a community catches malaria, does everyone get it?

Not always. Sometimes we go to a community, spend seven days there, do an active search. We’ll take slides of everybody who lives there [the diagnosis is made by testing a drop of blood collected on a slide]; sometimes it’s a hundred people. The Yanomami live scattered across many xaponos [Yanomam word for community houses]. We split up to cover them all. The helicopter pilot leaves us in the largest clearing; we stay in the nearest xapono, and from there we go on foot to collect slides from everybody. Then we come back, and the microscopist reads the slides. On the morning of the second day he starts releasing the results, and we go back to take them the treatment. If someone is really debilitated, in critical condition, we have a satellite telephone to notify [the base hub]. The helicopter will take the person to Surucucu because they have doctors and the basics there, if [the patient] needs to be taken to the hospital. And we stay in these villages seeing people for at least seven days.

Collecting blood to test for malaria in Makabei. The teams test all residents in every collective house they visit. Photo: personal archives

Have you continued to witness a lot of children dying this year, or have things improved a bit?

Things have improved a bit, but there are still problematic cases. Malaria is at a peak, and there are other diseases that were here before. The nutritional issue has improved in some regions.

Does malaria always coincide with the presence of illegal mining?

In this region [the Roraima highlands], yes. Malaria wasn’t endemic.

Are many people coopted and drawn to mining?

Young people are dazzled by the idea of having a cell phone, a boombox. So we have these young people, lost in the forest, and I wonder what the strategy is for showing them a new path. These young people have seen the worst of our society. We have a lost youth, boys who are armed, who’ve had contact with drugs and alcohol, things that lay totally outside this world. [The only white people] they knew were healthcare providers. When there wasn’t any malaria, we’d go into the xapono, weigh the children to check their nutritional status, do mass treatment for onchocerciasis [a parasitic disease of the skin and eyes], which is being eliminated in the territory, and vaccinate them.

Was it more about health maintenance?

It was more about primary care, and now we go in to treat critical cases of malaria and malnutrition. When we go into a xapono, we see these really sick, debilitated, anemic people whose vaccination cards are blank. And the healthcare team is still in emergency mode. We’re making progress; more providers are coming in to the DSEI [Special Indigenous Public Health District]. But what are the long-term measures? Those of us in the healthcare system are also going to have to think about this. I always say that Indigenous health care is not just about primary health care. You take care of a serious accident, someone who got shot, but you don’t have all the medications because supposedly we’re just doing primary care. But if we manage to rein in this major malaria outbreak, it would be possible to step up other actions. Today we’re trying to do everything together, but all spheres of government must bring the State inside the territory, with responsibility. I saw with my own eyes that mining operations really shut down. We could go in, provide care, see who had died so we could issue death certificates, remove them from the population census. But by the end of the year, we couldn’t go back there anymore because [mining operations] had resumed. And what are the proposals? A perpetual [public healthcare] emergency? That’s not going to work.

Did you see it up close when a great number of illegal miners entered under the Bolsonaro administration?

That’s exactly what I saw, what I see—the before and after. In this region [the highlands], there was no mining. People used to say there’s mining going on, way over there, but you never saw it; you didn’t hear the engines. It wasn’t like it was later. It was farther away from us and wasn’t a threat to Yanomami society like it is now—threatening to disrupt their culture, their way of life, and bring in so much disease and suffering. I started at the DSEI [Special Indigenous Public Health District], working in this region, and I came back six years later. Under the Bolsonaro administration, I spent more time in Amazonas state. Back then, everything was lacking.

Back then, were you also able to carry out rescue missions?

We were, but sometimes they’d say the helicopter had broken down. It would stay on the ground for 10 days and a whole lot of people would die [because some areas of the territory can only be reached by helicopter].

Are deaths from that period still underreported?

We’re still just starting to enter some communities, and you know the Yanomami have their way of dealing with death, of not talking about whoever has died. It’s not just any provider who can go there and they’ll talk to them. A newcomer won’t be able to write out death certificates. [The new person] will see the name there, and the Yanomami will just say “cross it out because that one died.” They won’t say how or when. That’s why we’ve been mixing more experienced workers with the newbies. Xitei is one place where we managed to do a good job identifying deaths in recent years. It’s an emblematic region, heavily invaded, and there are 1,500 Yanomami spread across 23 villages. I worked there before, and when I returned, I could see that the environmental and social degradation had been really bad.

A community near the Xitei healthcare hub is surrounded by mines. Illegal miners were expelled in early 2023 but returned to the area. Photo: Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

Which base hubs were you involved in reopening?

The ones I have been to were Parafuri, Kataroa, and Haxiu. Since October, we’ve also kept a fixed team in Maraxiu, which is a post that had been closed, formerly called Hakoma, and now we’ve built a house and it’s being inaugurated today [February 16, 2024]. In May 2023, I went into the Rio Parima region, where no one had been for a long time. In June, I spent six days in two Xitei region communities that hadn’t received any services in nearly three years. There had been recent operations, and the area was safe. We made a place for the team to stay, and we considered the possibility of a healthcare unit. Because of [an internal] conflict that started in May 2022, involving alcohol brought in by the miners, these two communities can’t get to the Xitei post, where a fixed team serves 23 communities. But the miners returned in September and reactivated the mining sites next to both communities. Since then we haven’t been able to provide them with care—only when they ask for critical patients to be airlifted out. But we aren’t doing any vaccinations in either community or conducting disease prevention programs, like for onchocerciasis and worms. I was so hopeful about resuming healthcare services, but that hope didn’t last for very many months.

Have you been able to eliminate the breeding grounds of the malaria mosquito?

We use mosquito poison inside houses; it soaks into the walls. If a community agrees to mosquito netting, we offer it. Not everybody likes it. You have to rely on a combination of actions to control malaria. Early diagnosis and treatment are essential, because you treat it and keep other people from getting sick. But it’s hard to talk about vector control in an area that has been ravaged by mining. There are many breeding grounds for mosquitoes because, besides the craters, there’s the garbage. The equipment that was burned is still there. There are gas cans, refrigerators, stoves, beer cans. The miners just leave everything. We don’t know where to start. We can tell them to collect the garbage that’s accumulating water, but then you walk 30 feet, 100 feet, and you’re at the craters.

Many people think you’re Yanomami because of your hair and body paint. Do you feel like a Yanomami or a friend of the Yanomami?

I don’t feel Yanomami because I’m not Yanomami. The Yanomami are the people who were born here, who live on this land. But my relationship with them, giving my life to be inside [the territory] with them… They call me waithërioma, which means courageous woman, because I was one of the first people who came in to set up the teams, who said that’s where they’re needed. They recognize this relationship of struggle, of giving. It’s not just friendship. The fact that I cut my hair like this was, first, because I think the way the Yanomami wear their hair is beautiful, and then also because it’s made my life and work much easier. I arrive in a community where they’ve never seen me before and the children come right over and jump on my lap. A rescue operation has to happen real fast: Who’s sick? This person. Let’s go! So there’s a mother with five kids and you’ve got to help her.

Why does it have to be so fast?

Because a helicopter costs a lot, it’s really expensive; you can’t just stand there chatting while the helicopter engine is running. You have to get there, pick up the sick person, and get out.

Does your appearance make contact easier?

My hair, the feathers, my necklaces. And the language too. If I came in speaking Portuguese with my hair like this, they wouldn’t approach me. I get there and speak to the patient in their language. And the children are calmer when they climb into my lap.

Editing: Claudia Antunes e Talita Bedinelli

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Spanish translation: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Diane Whitty

Infographics: Rodolfo Almeida

Editorial workflow, copyediting and finishing: Viviane Zandonadi and Érica Saboya

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum

Clara with body paint and a giant armadillo tail peeking out from under her arms. Speaking one of the Yanomam languages makes her work easier. Photo: Lela Beltrão/SUMAÚMA