Caio Pompeia has been conducting a detailed investigation of Brazilian agribusiness as a political phenomenon for over ten years, and is the author of Formação Política do Agronegócio (The Political Formation of Agribusiness), published by Editora Elefante in 2021. In an exclusive interview with SUMAÚMA, the softly spoken researcher meticulously describes how the formation and growth of the Instituto Pensar Agropecuária (the Think Agriculture Institute, or IPA) think tank has strengthened the political clout of agribusiness over the last decade. Based in Brasília, and boasting a specialized team, a permanent and consistent working agenda and a budget of more than half a million reais (around $98,500 US dollars) per month, the IPA is responsible for bringing together the discourses of regional, national and transnational agribusiness elites, and for the actions of the business-parliamentary movement that has increased the influence of the FPA (the Frente Parlamentar da Agropecuária, or Parliamentary Front for Agriculture, a pro-agriculture voting bloc) in Congress.

The IPA has supported concerted actions opposing the demarcation of Indigenous territories and the creation of Conservation Units, and in recent years has turned its attention to government food policies, including through an attempt to alter the Brazilian Dietary Guide, to improve the image of ultra-processed food products, which are related to increases in a number of diseases and public health problems such as obesity.

Understanding the reasons behind the growing strength of the alliance between farmers’ associations and food corporations is a vital part of tackling the climate crisis which has already brought an increase in extreme weather events, such as those that have, in 2023 alone, killed and displaced people and destroyed homes on the coast of São Paulo, in southeastern Brazil, and in the state of Acre, in the Amazon. A recent study by scientists in the USA, entitled Future Warming from Global Food Consumption, reveals that if current consumption patterns are maintained until 2100, the global temperature will increase by one degree Celsius, putting the goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions established in the Paris Agreement under serious threat. The main villains are foods with a high methane content (CH4), such as meat and dairy products

Methane is the second most abundant greenhouse gas, after carbon dioxide, and represents 17.6% of global emissions. Brazil is the fifth biggest producer of methane in the world, with agriculture responsible for 71.8% of such emissions, mostly generated by the digestive processes of cattle, according to data from the country’s System for Estimating Emissions and Removals of Greenhouse Gases. Agriculture is also the second largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in Brazil, and the main driver of deforestation and land conflicts, especially in the Amazon. According to a report by the Global Witness organization, meanwhile, Brazil has been the deadliest country in the world for environmental activists over the last decade.

INDIGENOUS PEOPLE PROTEST IN BRASILIA AGAINST PROPOSED LEGISLATION THAT WOULD INFRINGE THEIR TERRITORIAL RIGHTS, NOVEMBER 2015. Photo: Antonio Cruz/Agência Brasil

Caio Pompeia, currently a visiting professor at the Latin American Centre of the Oxford School of Global and Areas Studies, plans to spend this year studying how the different political strands of agribusiness will reorganize themselves after Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, commonly known as Lula, was elected as Brazilian president for the third time, following a campaign notable for its pro-Amazon, pro-combating-the-climate-crisis stance. Lula’s first weeks in charge have been busy, with agribusiness representatives proposing amendments to the provisional act that restructured certain government ministries, which, if approved, would weaken departments such as the Ministry of the Environment and Funai, the National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples. The sector also reacted to the comments of Jorge Viana, president of the Brazilian Agency for the Promotion of Exports and Investments, and Workers’ Party member, about the link between agribusiness and deforestation in the Amazon, made on a recent visit to China, and published a statement repudiating such claims. And a provisional decree has also just been approved in Brazil’s Chamber of Deputies which allows the deforestation of primary and secondary vegetation in an advanced stage of regeneration in Brazil’s Atlantic Forest, currently the most threatened biome in the country.

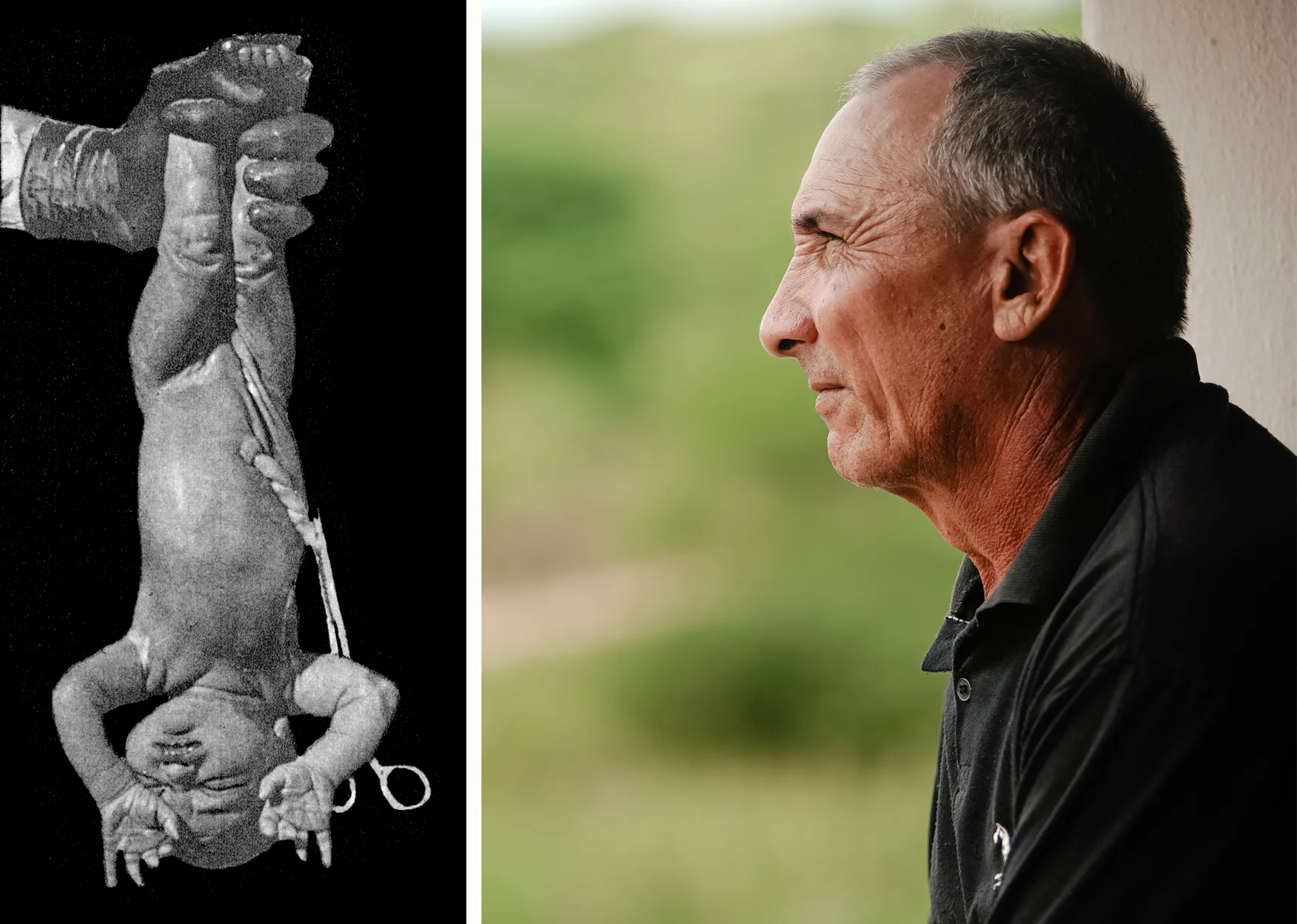

ANTHROPOLOGIST CAIO POMPEIA INVESTIGATES BRAZILIAN AGRIBUSINESS AS A POLITICAL PHENOMENON. HE IS AUTHOR OF THE BOOK ‘THE POLITICAL FORMATION OF AGRIBUSINESS’ RELEASED IN 2021 BY EDITORA ELEFANTE. Photo: publicity

According to Caio Pompeia, the term “ruralism” is not sufficient to explain the complexity of the power bloc that involves Brazil’s agribusiness sector but also “protects the reputation of corporations that exercise significant political influence, but prefer not to be visible.” “Evidently, (the term ruralism) has historical and current importance in Brazil, but it is far from capable of describing the participation, alongside farmers, of large agri-food corporations in areas of political consultation in Brasília, the role of which is to establish positions that will later be defended by the FPA,” says the anthropologist.

SEPTEMBER 2020: TRIBUTE TO THE FORMER PRESIDENT, THE RIGHT-WING EXTREMIST JAIR BOLSONARO, IN SINOP, MATO GROSSO. PHOTO: CLAUBER CLEBER CAETANO/PR

SUMAÚMA: What does your research reveal about the political agenda of agribusiness in Brazil?

CAIO POMPEIA: in my analysis, agribusiness is a dynamic and heterogeneous political phenomenon, characterized by both conflict and unity between its actors, such as that which led to the removal of (then Brazilian president) Dilma Rousseff from power (in 2016). The movement against her government began with segments of cattle farmers, who adopted more extremist and ideologically distant positions from Workers’ Party governments, and took approximately a year to gain significant space within the FPA, in the Agribusiness Council of the Federation of Industries of the State of São Paulo, and even within the Brazilian Agribusiness Association. In 2023, I plan to research how the different strands of agribusiness will reorganize themselves after Lula’s victory.

How has the political union of agribusiness been strengthened in Brasilia?

There was an informal political office maintained by cotton and soybean representatives from Mato Grosso, together with a few members of the so-called ruralist caucus in Congress. It was this office that, in 2011, became the IPA. And when the IPA grew in the mid-2010s, there were important changes in how agribusiness interests were represented in Brasília. The first was to place Brazil’s food system elites within a process of convergence, bringing discipline to the process of securing funding, unifying political discourses and organizing a more robust technical structure. Another important change was the renting of a mansion in Lago Sul [an affluent neighborhood in Brasília, with the highest per capita income in Brazil] and the creation of a team focused on representing business interests, which encouraged greater specialization in how these actors defended their interests. The third major change was the strengthening of the FPA’s strategic nucleus, which is made up of approximately two dozen members of Congress. This nucleus expanded its capacity, allowing it to act in a series of areas where it did not have the same power of influence. It is because of the IPA that agribusiness has been strengthened in such an unparalleled manner.

BRASILIA, OCTOBER 6, 2021: BOLSONARO HAS BREAKFAST WITH MEMBERS OF THR CATTLE RANCHING LOBBY. PHOTO: ISAC NÓBREGA/PR

But agribusiness was already a politically strong sector even before the IPA, wasn’t it?

Agrarian elites have historically held a lot of power in Brazil, of course. But they have pursued a sustained political coupling with representatives of industrial and tertiary activities, as agribusiness is characterized, since the 1980s, to tackle the loss of influence of agricultural commodity (or primary product) chains in politics, due to a set of economic changes in Brazil. The IPA represents the most notable success of this program of political unity. With it, “agro” (a shortened form of agronegócio, or agribusiness, used in marketing materials) began to have a greater impact on themes on which it had previously been more defensive, such as the environment. In recent years, they have greatly expanded their activities in a number of areas, beginning to address food policy, for example, including through campaigns to change the Brazilian Dietary Guide. Now, in Lula’s third term, agribusiness is disputing the main reforms and the actual organizational structure of the Esplanada dos Ministérios (where Brazil’s government ministries are headquartered), as we are seeing.

What is the role and participation of industries in the IPA?

The IPA started out as an office set up by agencies representing agriculture and ranching, by farmers. During discussions about the changes to the Forest Code, industrial corporations began to participate more actively and contribute financially to strengthen the institute. In 2015, there was a significant change when the Supreme Court prohibited the corporate financing of electoral campaigns. After this prohibition, the presence of industrial associations financing the IPA increased significantly. As of 2017, industrial interests became even more numerically preponderant than farmers’ associations. This was also seen in their increased participation in the leadership of some IPA committees, such as those on the environment, agrarian issues, international relations and food.

What are the IPA’s main funding sources and what is its annual budget?

Funds are transferred monthly by around fifty agribusiness-linked member associations. The total funding is more than half a million reais (around $98,500 US dollars) per month.

THE CHAIRMAN OF THE CHAMBER OF DEPUTIES, ARTHUR LIRA, AND THE FEDERAL DEPUTY PEDRO LUPION, TAKE OFFICE IN THE NEW BOARD OF THE PARLIAMENTARY FRONT FOR AGRICULTURE IN 2023. Photo: publicity

Does the performance of IPA committees correlate with the FPA’s performance in Congress?

Yes, precisely. The consolidation of the IPA increases the destabilization of the boundaries between public and private in the representation of interests. There is a joint process of creating proposals (for laws) that may be politically effective in Brasilia. Previously, agribusiness actors tried to construct a position either individually or collectively and then engage with parliamentarian A, B or C to have that position defended in Congress. Now, with the IPA, the position is developed collectively from the outset. There is a systematic dialogue, with a set of mediations, in this mansion in Brasília. There is therefore a business-parliamentary construct from the start. The IPA organizes the main regional, national and transnational agribusiness elites in Brazil, assisted by specialized technical agents, and working together with a group of parliamentarians from the FPA. From these business-parliamentary decisions, the positions defended in Congress spread, through negotiations with party presidents and leaders in Congress and the Senate, fragmented work with members of parliament, and negotiations with government leaders.

What is the position of this pragmatic agribusiness alliance on the territorial rights of Indigenous peoples and traditional communities?

Resistance to the territorial rights of Indigenous peoples and traditional populations is obviously a very old issue and involves agrarian elites on a regional basis, but in the major intersectoral forums of agribusiness it has become more significant. The case of Raposa Serra do Sol (an Indigenous territory located in the state of Roraima where the Ingarikó, Macuxi, Patamona, Taurepang and Wapichana peoples live, and which was officially recognized in 2005) was important in this sense, because, in addition to causing a great deal of animosity on the part of the elites in the state in which the disputes took place, it also mobilized agribusiness leaders from every region of Brazil, who feared that the consequences of decisions on this case could influence their enterprises.

AN INDIGENOUS WOMAN PROTESTS AGAINST ‘THE POISON PACKAGE’ OF LEGISLATION AT THE TERRA LIVRE CAMP IN BRASILIA IN 2022. PHOTO: MÍDIA NINJA

The theme of the demarcation of Indigenous territories started to become more high profile through two political successes [for agribusiness]: the weakening of the creation of rural settlements for agrarian reform and the change to the Forestry Code. Based on this, they decided the next step would be an orchestrated action against the demarcation of Indigenous lands and the territories of other traditional populations, and the creation of new conservation units.

This process was effectively constructed within the IPA in the following years, to the point that a committee on questions relating to land issues was set up within the institute. Opposition to Indigenous rights gained strength within the FPA, and began to exert considerable influence over Dilma Rousseff’s government. It is important to note that at the time, Proposed Constitutional Amendment 215, which would have transferred demarcation processes from the executive to the legislative, was a major issue in Congress [the proposal was ultimately shelved after a great deal of struggle by Indigenous and socio-environmental organizations]. The process gained more momentum under Michel Temer (Brazilian president between 2016 and 2018), but anti-Indigenous positions gained even more influential space under the Bolsonaro government.

If agendas up to 2017 were mainly concerned with demobilizing the recognition of Indigenous territories, after that, plans to open up already approved Indigenous territories, and to insert them into national and international agricultural commodity production circuits, began to gain momentum. Under the Bolsonaro government, as we know, non-Indigenous actors were incentivized to enter already approved Indigenous territories, with equipment, seeds and production processes.

The Brazil Climate, Forests and Agriculture Coalition is in favor of the demarcation of Indigenous territories. What does this mean as a counterpoint to the agribusiness agenda in Congress?

The Brazil Climate, Forests and Agriculture Coalition, which emerged between 2014 and 2015, didn’t mention Indigenous territories in its launch manifesto. It mainly began to address this issue at the end of 2018 and, since then, has highlighted it in some of its positions. This is a very significant change from the positions of agribusiness representatives who are applying pressure against the demarcation processes. However, so far we haven’t seen any effective action, through pressure groups in Brasilia, in favor of these rights. It is essential that positions on the subject are made concrete, especially in the major battles in Congress or in Supreme Court judgments, with broad, horizontal dialogue with traditional peoples. In 2023, one of its main objectives of the FPA is to defend the “timeframe thesis”, which adds the condition that Indigenous peoples must have occupied their lands on October 5, 1988, the date of promulgation of the Brazilian Constitution, to the demarcation process. It is important that the Coalition mobilizes its instruments of influence, together with its privileged position in the public sphere, to effectively oppose this.

How would you describe the positions of the different strands of agribusiness in the 2022 elections and what do you expect in the years to come?

A large part of the agricultural bases led by soybean and cattle farmers adhered to the agendas of Jair Bolsonaro’s government almost without restriction. These actors and their representative entities, such as the Association of Soy and Corn Producers of the State of Mato Grosso, have demonstrated the greatest animosity to the Lula government. The main reasons for their opposition to the current government are ideological, but are also linked to land and environmental agendas.

The second important strand is formed of some of Brazil’s main agricultural associations, which have a slightly more modulated position, which I would call conservative. They harbor a significant distrust of government agendas, but are more pragmatic and less closed off to negotiation.

A third stream of actors, which I would call fickle, is made up of large agro-industries, both national and transnational. Out of Lula and Bolsonaro, many preferred Bolsonaro, but were politically adept enough, as they always are, to dialogue and keep channels open with both candidates. The increase in the prices of agricultural commodities was very important for them. This increase offset some dissatisfaction with the Bolsonaro government, such as diplomatic slippage in relation to China. There is a concern on the part of industries with capital-labor relations and how they might be modified under a Workers’ Party government.

The decarbonizers, as I have been calling the actions of some national agribusiness associations, such as the Brazilian Agribusiness Association, have clearly criticized the Bolsonaro government, mainly for its anti-environmental policies, as they are highly susceptible to the risk of harm to their image and pressure from investors, importers and organized segments of civil society, especially in Europe. But although they rejected Bolsonaro, they didn’t want Lula either. These actors chose to strengthen what is conventionally called the third way, the candidacy of Simone Tebet (of the Brazilian Democratic Party), which they strongly supported. Not that they expected her to win, but they thought she would help ensure the elections went to a second round runoff, which is what happened, and, with her support for Lula, that she would insert herself as an influential leader within the government.

How can the land rights agenda move forward in Brazil in the years to come, considering the size and strength of the ruralist caucus?

It is essential that the values and expectations of those who ascended the ramp of the Palácio do Planalto (Brazil’s seat of government) in January are truly respected, including through the territorial rights of Indigenous peoples and traditional populations. That the government, when under pressure or having to arbitrate between internal conflicts or difficulties with its base in Congress, prioritizes these rights, because, obviously, conflicts are to be expected.

It is also important that the government implements, at the beginning of its term in office, vigorous and long-term actions to promote environmentally sustainable and socially fair economic activities. The announcement, at the beginning of this year, of the resumption of demarcation processes in some Indigenous territories is very welcome.

A LARGE CHESTNUT TREE STANDS ALONE AMID LAND CLEARED FOR CROP FIELDS IN SINOP, MATO GROSSO. PHOTO: PABLO ALBARENGA

It would also be pertinent to create a state strategic center, like Embrapa, (the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation), with a specialized team and substantial resources, so that Brazil can take a leap forward, which it can, in promoting economic activities that contribute to strengthening biodiversity, keeping forests standing and respecting the ways of life and the worlds of traditional populations.

With the increased participation of Indigenous women in institutional politics and the central role given to combating the climate crisis under the new government, how will the ruralist sector act to maintain the slogan “agro is cool”?

Since the beginning of the 2010s, food system elites have led an organized strategy to capture hearts and minds in Brazil. As a result, they compete for the national imagination, with notable political, economic, social and cultural consequences. This has been a partially successful operation. It is expected that such elites will give more impetus to communication initiatives, adapting them to the new configuration of forces in Brazil.

Spell check (Portuguese): Elvira Gago

Translation into Spanish: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: James Young

Photography editing: Marcelo Aguilar, Mariana Greif and Pablo Albarenga