At 7:43 on a Sunday evening in August, in the main square of Melgaço, a city of 28,000 on Marajó Island, in the Brazilian state of Pará, the scent of popcorn and cotton candy mixes with the smell of exhaust from a motorcycle parade being held for a mayoral candidate. Kids stop kicking their football to watch the unusual scene. To the sound of horns, shouts and whistles, candidate Éder Vaz, a former municipal education secretary with the União Brasil party, is leading the motorized procession from the only truck, the flat bed of which is crammed full of like-minded campaigners. Fireworks fizzle up into the sky from an empty lot next to the house occupied by the mayor, José Delcicley Viegas, or Tica Viegas, a 37-year-old former logger who made his wealth in a piece of the forest and who is working to elect Vaz instead of his own cousin, Zé Viegas, the Brazilian Democratic Movement candidate. In front of the three-story house located near the square, the party’s number, 44, echoes at high decibels from the sound equipment mounted on a car, exhaustively repeating a jingle that cheers a group of canvassers.

The campaign for October’s municipal elections had officially kicked off two days earlier. In the morning, according to a boatman who provided services to the politicians, Vaz’s aides and a few council members running for reelection had spent R$ 20,000 (3.600 dollars) to take 20 motorboats to visit Ribeirinho (traditional riverside dweller) villages far beyond the urban area. At least 74% of households in Melgaço are rural, according to the 2010 Census, and many sit along the banks of Rivers and Streams.

The boats could be seen arriving and departing from the city’s port, each carrying up to 12 passengers wearing União Brasil shirts. Tiny party flags blew in the wind at the boats’ corners. “They spent R$ 10,000 on day rates plus R$ 10,000 in gas. In just one day,” says one of the boatmen. That Sunday, nearly every vessel in the city was rented out to campaigning politicians. They had gone to bring lunch to far-flung electors, people who struggle most of the year to provide three meals a day for their children. Tica Viegas, a two-term mayor, says the fuel bill was paid by supporters. His Instagram page shows the same crowd dressed in blue visiting Ribeirinho villages. They were throwing a party where it’s usually silent.

Boat and motorcycle rallies are part of the election in Melgaço, one of Brazil’s poorest municipalities, where people die because the boat ambulance has no fuel

There was an air of abundance in the municipality with Brazil’s worst Human Development Index (HDI), where just a few months earlier a mother had lost her baby because the municipal government’s motorboat ambulance was out of fuel when she went into labor. With no transportation, she couldn’t reach the hospital on time. That same evening, she was sitting a few meters from the motorcycle parade, at the São Miguel Arcanjo Parish Church, where young and old people were playing bingo. They strained to hear the caller, who was calling out numbers in the middle of a campaign brouhaha. They were trying to win prizes ranging from thermal bottles to bath towels, shorts, a blender, and a stove. The still-grieving mother avoided talking about the child she had lost.

The bountiful fuel on that campaign Sunday is also frequently lacking to transport the 360 municipal school students who attend the Alfredo Lopes Primary School, which sits near the Soiaí River, says the principal, Regimero Moura, 39. “That is why there were only 12 school days this month,” he says. The city’s teachers say that some students in the region take 12 hours to go to and from school. “The boat comes to pick up [the first students] at 6:00 o’clock and reaches the school at noon. It’s the same on the way back,” says Ediele Lima, a coordinator with Caritas in Melgaço and a member of the Municipal Council on Child and Adolescent Rights. After the long journey, the children are also subjected to degrading conditions at the institution, the principal says: “The school was refurbished by the municipal government in 2022, but they made the roof very low, so it gets very hot during class. It’s definitely not up to [Education] Ministry standards.”

At 11:58 in the morning on that same Sunday, along the banks of the Soiaí, half an hour by boat from Melgaço’s urban area, Rosenise Pantoja, 31, a mother of six, complained about the food provided at the school by the municipal government. She says the porridge-like rice that is served to children contains woodworms and borers, small beetles. Served with artificially-flavored juice and saltine crackers, it fails to satisfy the kids’ hunger. “There’s never enough food. There’s hardly any,” says Rosenise. “Sometimes it comes rotten, smelling bad.” The kids play around their mother, who shares a three-room wooden stilt house with her partner, Junielson, her kids and two siblings. Altogether, ten people live in the isolated home, without any neighbors, along the river’s edge. “The mayor has never come here,” she guarantees.

Rosenise Pantoja’s daughters suffer from the food served at the city’s schools: food is oftentimes lacking or is rotten

A report produced by the Ministry of Human Rights and Citizenship in May 2023 says that in Melgaço, “there were many situations where pregnant women ended up losing their babies because there was no motorboat or fuel” and that “there are many children who go to school hungry and find no school lunch and, when they do get it, the amount is insufficient for their nutritional needs (half a cup of juice and three crackers).”

A letter released in March and signed by the Justice and Peace Commission of Melgaço, Caritas, and the Youth Ministry says the scenario in the city’s education has contributed to “an overwhelming school drop-out rate and the luring [of kids and adolescents] to the world of drugs and prostitution by recruiters.”

According to another report, this time issued by the Chamber of Deputies in regards to transfers to municipalities, Melgaço received R$ 3.9 million (710.000 dollars) from the National Education Development Fund in 2023. This includes R$ 1.7 million (309.000 dollars) for school transportation and R$ 1.2 million (218.000 dollars) for primary school meals. By August of this year, R$ 3.7 million (675.000 dollars) had been received – R$ 1.5 million (273.000 dollars) for transportation and R$ 871,000 (158.000 dollars) for school meals.

The mayor denies there is a shortage of gas, lack of school transportation or problems with school food quality, although he admits that food sometimes arrives late because of difficulties in delivery. Yet in Marajó, an archipelago that goes viral on social media from time to time because of inflammatory and fake accusations sexual exploration of boys and girls, the politicians aren’t interested in protecting children beyond the internet. They would rather turn them into the political propaganda of a religious moralism that seeks to consolidate their power in the region and have a flag to wave at the country’s conservative voters. With their false discourse of helping these children, they end up stigmatizing them and violating them all over.

There are six kids living at Osias Gonçalves de Lima’s home, a Ribeirinho who receives Bolsa Família benefits and who sometimes only has açaí, chicken and cassava flour to eat

Money for the church

Located 249 kilometers from Belém, or 14 hours by catamaran, Melgaço is one of the 17 municipalities on Marajó Island. It sits on the archipelago’s western side, one of the most isolated areas of the Amazon. It is made up of dirt roads and plastic refuse, which flows to the shore where the only new buildings are the municipal administration office and the Municipal Chamber. From the broad treeless sidewalk, to the bay of cloudy brown water that bears the same name as the city.

There are 22,311 residents who receive federal Bolsa Família benefit payments (80% of the city) — in August they were paid R$ 5.6 million (1 million dollars) out of public coffers, or an average monthly benefit of R$ 821 (150 dollars) each. During the first round of elections in 2022, 8,042 votes (64%) went to Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, while 3,857 voters (31%) chose Jair Bolsonaro. Lula was also the top vote-getter in the archipelago’s 16 other municipalities. With a population of 591,000, Marajó Island is home to 438,319 registered voters, according to the Supreme Electoral Court — 7% of Pará’s voters. It is no accident, says Magali Cunha, a researcher at the Institute on Religion Studies, that right-wing Evangelical are trying to siphon votes from the Workers’ Party in the region.

She says one of their main methods is to appeal to conservative electors’ indignation by appealing to the “religious popular imagination regarding sexuality.” “These themes of sexuality began to be widely explored in this line of defending family, denouncing what the leftists were doing around sexuality. Issues like feminist rights, LGBTQIAP+, would be a threat to the Brazilian family, to children. And so the left should be confronted,” says the researcher.

Through the Bereia Collective, a fact-checking agency specialized in religion, Magali followed the case of gospel singer Aymeê Rocha, who went viral in February after performing a song evoking sexual exploration in Marajó on a music program. “There’s lots of organ trafficking there, it’s normal there. There is ‘hard level’ pedophilia there. Kids who are 5 years old, when they see a boat with tourists coming from elsewhere, they go out in a canoe [6-, 7-year-olds] and prostitute themselves for R$ 5 (1 dollar),” Aymeê told the judges panel of the Dom Reality show. This statement came after singing a verse that went: “In the meantime in Marajó/João disappeared/Waiting for the reapers of the great fields/The Amazon burns/A child dies/Away the animals go/Overheated by their brothers’ ego/A gospel of Pharisees.”

It quickly gained traction on X, formerly Twitter, and was reposted 200,000 times in just one day. Millions of people who follow artists and influencers entered the debate, indignant, they spread Aymeê’s words. “The articulation online was very clear, the way it grew and went viral. It spread very quickly. At the time, I thought it seemed to be highly articulated,” says Magali Cunha.

Evangelical missionaries then took advantage of the buzz around the topic to launch a campaign to raise funds to fight sexual violence in Marajó. A partner at the Akachi Institute, an organization connected to Zion Church, which is responsible for the crowdfunding effort, Henrique Laino, 32, ran for city council member in São Paulo in 2020. Millionaires in business, like textile industrialist Ricardo Steinbruch and capital manager Patrice Philippe Nogueira Baptista Etlin, donated to Laino’s campaign. Sarah Hayashi, the founder of Zion Church, who died in July, was friends with former minister Damares Alves, currently a Senator representing the Federal District for the Republicanos party. Zion Church says on Instagram that it has provided 2,600 medical appointments in Marajó since 2019, including psychological and dental visits, and has distributed food, bibles and materials to prevent child sexual abuse.

It didn’t take long for the internet to remember the speeches Senator Damares made when she was at the helm of the Ministry of Women, Family, and Human Rights under the Bolsonaro administration — accompanied by fake content, like a video showing children in Uzbekistan as if they lived in the archipelago. “We have images of our Brazilian children, 4 years old, 3 years old, kidnapped, and when they’re brought across the border, their teeth are ripped out so they won’t bite during oral sex,” Damares said during a service at the Assembly of God church in Goiânia, in October 2022, while she was still with the ministry. “We discovered these children eat mushy food to keep their intestines clean for when it’s time to have anal sex,” she added. It was later found that Damares had taken inspiration from lies told on internet forums like 4Chan, used by people on the far right who believe in conspiracy theories where satanic pedophiles control part of the world.

Formerly a minister under the Bolsonaro administration, Damares Alves uses lies from internet forums as the basis for her speeches on child sexual exploration in the archipelago. Photo: Lula Marques/Agência Brasil

The Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office took notice of the statements made by Damares and asked that a judgment of R$ 5 million be entered against her and the federal government because of the lies about the population. The senator was accused of spreading “prejudicial and sensationalistic information about the people of Marajó, with no connection to reality and no evidentiary basis,” reads a passage from the civil public action. The prosecutors combed through other speeches Damares made and discovered that on at least two other occasions, in 2019 and 2022, she had lied about Marajó. The lawsuit is over 5,000 pages long. Damares’s attorneys have been unable to corroborate what she said in her speech.

“It’s a strategy Damares has used for many years, since she was giving speeches in churches. She started this,” says Magali Cunha. “Marajó comes into Damares’s speech precisely in this strategy of working with imagination, yet at the same time offering examples far-removed from people’s reality. She talks a lot about Europe, she mentioned a Swedish brochure on masturbation. This thing about the Amazon comes in too. Marajó as a supposed isle of savages, this distant place, that people are unfamiliar with. There’s an appeal to indignation to create an attitude.” The attitude is, oftentimes, voting for the far-right.

The religious appeal of matters related to sexuality, the researcher says, also has a dimension related to an educational agenda. The extreme right claims the left are “eroticizing” children. They talk about the gay kit, the dick bottle and funk dances at schools “This began to be adopted when the far-right was still taking shape in Brazil. Then it elected Bolsonaro in 2018. Today, it serves as the agenda for maintaining Bolsonaro-ism,” the researcher says.

By message, Damares said that for years she has read in books, news stories, reports and lawsuits about cases of sexual exploration in Marajó and that in 2019, “no longer able to just read, watch and listen, I went to the area to confront this subject through public policies.” “How do you want me to prove it? Do you want me to go find videos? Photos? Bodies? It’s my obligation? Do I have to prove every report that reaches me? No! I have to send it to the person who is obliged to investigate,” she added.

Talk about the sexual exploration of children and adolescents in Marajó is nothing new. A Parliamentary Inquiry Commission that wrapped up in 2010 investigated sex crimes in the archipelago over three years, becoming a topic of national discussion. The results of its work included making it a crime to rape a vulnerable person, which is when the victim is under 14 or has a deficiency. Led by a retired bishop in Marajó, the Right Reverend José Luis Azcona Hermoso, who at 84 years old has been admitted to a hospital in Belém, its reports suggested girls were selling sex in exchange for food. Some reportedly did this on ferries traveling through the Tajapuru Tidal Channel, near Melgaço, taking men from Belém to Macapá, and from there to the Free Trade Zone of Manaus.

Sex crimes do and did indeed occur in Marajó. According to the Annual Report on Brazilian Public Safety, in 2022 there were 273 cases of rape of a vulnerable person (child, adolescent or disabled person), or 49 for every 100,000 inhabitants — there is no data for 2023. A high number, but not much different from other parts of Brazil. In Pará, for instance, there were 3,732 rapes of a vulnerable person in the same year (46 for every 100,000 inhabitants). But in Roraima, there were 95 rapes for every 100,000 inhabitants in 2022 — but this high ratio does not prompt Damares’s electors to talk about the children there. None of the five cities in Brazil with the highest rates of rapes of a vulnerable person are in Marajó.

Since March, the Bereia Collective has not tracked any relevant movement on social media in relation to the lies about Marajó, says Magali Cunha. It was not for lack of effort from politicians who support Bolsonaro.

On June 6, three congressional members who back the former president — Senator Zequinha Marinho (Podemos for the state of Pará), Federal Deputy Silvia Waiãpi (Liberal Party for the state of Amapá), and Federal Deputy “Delegado Caveira” (Liberal Party for the state of Pará) — were in Melgaço for a “public hearing” aimed at “investigating reported cases of sex crimes committed against children and adolescents on Marajó Island,” according to the document filed with the Chamber of Deputies. It was actually external diligence by the Senate’s Commission on Human Rights, so the politicians could explore real cases of sexual violence in a sensationalistic way, while also distributing money from congressional amendments. “I organized the event,” Mayor Tica Viegas told SUMAÚMA. On social media, he describes himself as: “A man protected by God, the Lord is my rock and my fortress.”

Deputy Silvia Waiãpi, Deputy “Delegado Caveira” and Senator Zequinha Marinho (right) were in Melgaço. Photos: Renato Araújo, Mário Agra and Zeca Ribeiro/Brazil’s Chamber of Deputies

At the time, Senator Zequinha Marinho gave the mayor a symbolic check of R$ 500,000 — while giving another, for R$ 1 million (91.000 dollars), to a pastor with the Assembly of God church in Melgaço, Elvis Ribeiro. SUMAÚMA asked what the purpose of the check was, but Marinho did not respond by the time we published this story.

“Is this here the Base?” Zequinha Marinho asks an adviser during the event, with a microphone in one hand and a paper in the other. The senator appears in a video shot during the meeting, to which SUMAÚMA had access: “Humanitarian Base [of the Assembly of God], right? Training women, where are the women here in the auditorium? Raise your hands! (sic) Women love to learn to make money, right?” Marinho says. “I’d like to give to you [pastor Elvis Ribeiro] as well, just like I gave the others, an official letter that costs R$ 1 million, so that the center… the community action base can develop these actions to train women here in Melgaço so they can have a minimum of autonomy in financial matters, making money,” he concludes. Next, the far-right politician gives the check to the pastor.

Mayor Viegas said he will have to return the money the municipal government received: “It was an amendment [for medium and high complexity healthcare],” he explains. Melgaço has no health units providing this type of care. “It will probably go to another municipality,” he said.

According to Ediele Lima, a Caritas coordinator in Melgaço, “this public hearing was nothing more than a reaffirmation of the political alliance between the mayor and Evangelical churches.”

Pastor Elvis Ribeiro is an ally of Samuel Câmara, the president of the Convention of the Assembly of God in Brazil, one of the arms of the Assembly of God church — which gathers 12 million of the 42 million Evangelicals in Brazil, according to the last calculation done by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics, in 2010. In 2023, the church built the enormous “humanitarian base and temple” in Melgaço, as is read on the façade, which received funding from the extreme-right Zequinha Marinho. It serves Evangelicals with social assistance initiatives. Once a month, the pastor comes from Belém to hand out food at the stilt houses built in the peripheral areas of Melgaço, according to residents who spoke with SUMAÚMA.

Pastor Elvis Ribeiro (left) received a check for social projects at the Assembly of God church in Melgaço; he is connected to Samuel Câmara (right). Photos: reproduced from Instagram and Thiago Gomes/Folhapress

Samuel, in turn, is the brother of federal deputy Silas Câmara, a Bolsonaro supporter representing the state of Amazonas for the Republicans — and the president of the Evangelical Parliamentary Front in the National Congress, which joins 213 of the 513 deputies and 26 of 81 senators. The owner of the Boas Novas radio and television network, the family also includes Dan Câmara, another brother who was a former Military Police commander elected to represent Amazonas as a state deputy and one of the men convicted in the “leech scandal,” a scheme that siphoned money from amendments to acquire ambulances in 2006.

The extreme-right Evangelical offensive also included, in the same month as the Melgaço hearing, a visit to the municipality of Marajó by Evangelical Federal Supreme Court Justice André Mendonça. According to SUMAÚMA’s findings, he was at the Assembly of God humanitarian base.

Asked for comment, Mendonça said he was in the municipality on a “missionary and Evangelistic trip.” “Melgaço has one of Brazil’s worst IDHs and the Assembly of God Church adopted the city to try to transform the social and economic reality of its people,” the minister said.

“When I was there, I saw poverty and the Brazilian State’s abandonment of a needy population without any prospects. I was with mothers who said they dreamed of one day having a pediatrician in town. I visited homes the Church built and delivered free of charge to the people. I met families who, thanks to these homes, were able to use a toilet in their home for the first time. I accompanied doctors, psychologists, and other health workers from the Church who traveled to the city and, in a few days, provided care for over 1,000 people.”

Silas Câmara (left), presides over the Evangelical Parliamentary Front in Congress, and Dan Câmara (right), a former Military police commander; Minister Mendonça (center) visited Melgaço. Photos: Mario Agra/Chamber of Deputies, Nelson Jr./SCO/STF, and Anny Oliveira/Chamber of Deputies

On another front, in the Legislative Assembly of Pará, deputies like Rogério Barra (Liberal Party), the son of a Bolsonaro-supporting mayor candidate in Belém, Éder Mauro, are trying to get a new Parliamentary Inquiry Commission to look into sexual violence in Marajó, making this subject the center of attention once again.

In Melgaço, in early August, an Evangelical service held in front of the mayor’s house, in the middle of the sidewalk, sewed up the Assembly of God’s support for Éder Vaz’s candidature, running under the União Brasil party. According to the 2010 Census, there were 8,910 Evangelicals in the municipality, with 7,177 belonging to the Assembly of God, compared to 14,730 Catholics. Data on religion from the 2022 Census should be published next year.

The campaign for Éder Vaz (left) included an Evangelical worship service in front of the home of Melgaço’s current mayor, Tica Viegas (right). Photo: reproduced from Instagram

Bone soup

Rosenise, the mother of six whose kids are barely fed at school, had eaten chicken, açaí and cassava flour for lunch. On the wooden floor a minibar fridge is off and its door is open. Inside is just a plate of cassava flour and an empty PET bottle. Sometimes the meal is just açaí, she says. Sometimes she kills a duck. A beneficiary of Bolsa Família payments, she gets R$ 1,700 (310 dollars) a month. Once she is paid, she can buy some meat. “It’s much harder in the winter; there’s not as much açaí. If it weren’t for government help, we’d go hungry,” she says. Rosenise recently underwent an operation on a cyst and she talks about how hard it was to get medication. “There’s never any in the hospitals, you always have to buy it.” She and her family drink river water. There is no shower and no sewerage. Baths are taken in the Soiaí as well. Members of the Aliança Eterna Assembly of God, a small Ribeirinha Evangelical church, they usually go to church often. “They just help with the prayer really,” says Osias, Rosenise’s brother. He looks at the river. A huge barge loaded with wood logs is passing by. “It comes from way up in the interior of Portel. A lot come from there,” says our boatman. “Mostly clandestine.”

A few minutes by motorboat, living along the banks of the Constantino River, José Maria de Lima, 49, a father to two grown women, is staining his hands while harvesting açaí. He sells the 14-kilo bucket, harvested over two days of work, for R$ 38 (7 dollars). Born along the Buiuçu Tidal Channel, he shares a small stilt house with his daughters, sons-in-law, and grandchildren. There are six people. Lima has a monthly income of R$ 1,000 (182 dollars): R$ 600 (109 dollars) comes from the Bolsa Família payments and the rest from açaí. “There are days when we can’t even buy food,” he says. “Then you just drink açaí.” Lima says he lived in a remote place, right there in Marajó, where the people had no food, so they ate salt. “Back where all you could hear was the frogs croaking. They ate 1 kilo of salt, that was dinner. They drank the açaí, they would dip the spoon in the salt and eat.”

At José Maria de Lima’s house, which receives R$ 600 in Bolsa Família benefits each month, açaí is sometimes the only food available

When they had a shotgun, it was Pacas, Deer, Sloths, Alligators. Now, not even this, not just because they had to sell their gun to get more money, but because the animals disappeared. Lima occasionally sees a Manatee, eating the Creeping Rivergrass along the river’s slopes. He also sees lights in the sky, he says. “A reddish light that moves.” He thinks it’s a sign from God. An evangelical, he suffers from chronic pain in one of his arms, which was bitten by a Caiman last year. “Some nights I can’t sleep from so much pain,” he says. On his other arm is a huge scar from when he struck himself with a machete while cutting a palm heart from a tree. His hands bear the marks of a worker. “The wood used to help a lot, but there’s no more wood now. Andiroba. Hernandia guianensis. Virola. It’s rare that you find it.”

In Breves, a municipality with a population of 107,000 that is popularly known as “the capital of Marajó,” there was a timber company that employed 5,000 people, says Zairo Benjó, a teacher in Pará’s state education system and with a specialist degree in cultural studies and public policy at the Federal University of Amapá. A resident of Breves for 30 years, Benjó is emblematic of Marajó natives: the son of Indigenous people and a descendent of slaves and Sephardic Jews who arrived to the island in the 19th century. “Here, the money used was the dollar. There was an American timber exporter, people spoke English in the ’90s,” he recalls. That is why the streets are made of sawdust from bygone timber companies that would rip the trees from the Amazon, as well açaí seeds, used by the load to fill lowland areas on the municipality’s periphery.

After his son drowned in the river, Domingos de Oliveira (left) created a water distribution system; Zairo Benjó (right) also fights for the right to water

After the rubber boom came the rice boom, the timber boom. Far earlier, Portuguese explorers had navigated through Marajó, including Duarte Pacheco Pereira, in 1498. Other Europeans had seen Indigenous women armed with poisoned arrows, the Marajoara people. “Large, powerful, and complex chiefdoms along large swaths of the Amazon River,” wrote Robert Carneiro, an anthropologist from the United States. Melgaço later grew from Guarycuru Village, the last Portuguese border in the north. In 1758, it became a town. In 1961, a city. The motorized boats came, providing transportation against the tide. Then banks, and state agencies. Electricity. Legends started disappearing, nobody talks much anymore about the River Dolphin, about the man in white who turns animal and impregnates women who enter the water after nightfall. Not even about the sorceress who whistles when no one is near. There is nothing left of Nheengatu, or of any other Indigenous language that was spoken there. In the end, the government contracts came. Today, government jobs and Bolsa Família benefits are driving the economy.

A resident of Jardim Tropical, a neighborhood on the outskirts of Breves built on top of sawdust, Domingos de Oliveira, 66, lost his youngest son Thiago after he drowned in the Parauaú River when he was 4 years old. He had gone to bathe in the river because the house had no running water. Afterward, Domingos built a distribution system with his own hands that draws water from the river for 350 families. “I did it to never again see anyone go to the river for water,” he says. He lives next to an enormous empty, unused water tank, a public project that has gone on for 11 years now, at a cost of at least R$ 30 million(5,5 million dollars).

In the meantime, in the Panema Stream, at the extreme other end of the city, midwife Maria Ferreira, 81, is hungry and is getting ready to chop wood to heat water from the stream that has spent three days decanting in basins outside of her stilt home. After decanting, she boils the water. Next, she adds some drops of sodium hypochlorite, a purifier widely used by those who quench their thirst along the Amazon’s rivers. That afternoon, Maria would skip lunch. She didn’t have enough money to buy food for the day. Her last meal had been lunch the day before — “soup with some bones somewhat gave me, highly seasoned, with this pasta the reverend gave me.”

Water from the stream is used for bathing, consumption, and transportation on the outskirts of Breves, where Maria Ferreira de Souza’s family lives

A study done by Ipri, an FSB Holding company conducting reputation and image surveys, showed the number of candidates in Brazil who identify as religious rose from 2,215 in 2000 to 7,206 in 2024. On Marajó Island, Evangelical temples are starting to spring up in the landscape. Luce Mara Lobato, a social worker and a coordinator with the Justice and Peace Commission of Breves, has seen them: “Lots. Too many. One on every corner. It was fast; it started in the 2018 election. From then to now there was an explosion [in the number of Evangelical churches]”. While going by boat from Breves to Melgaço along rivers like the Parauaú or along the smaller streams, there are dozens of little wooden churches, one every 100 meters, nearly all are Evangelical. They dot the riverbanks, some colorful, others are being refurbished.

According to the social worker, religious people are found at the hospitals, in WhatsApp groups organizing visits to the sick, and in incursions up the river, where they promise to exorcize the demon from alcoholic men. The report produced by the federal government’s Marajó Citizenship program says: “missionaries from the Neo-Pentecostal churches in Melgaço were reportedly interfering with guidance on vaccination, particularly hindering vaccine coverage of children and adolescents.”

Before Marajó Citizenship was launched, it was called Embrace Marajó, a program created by former-Minister Damares that was replaced under the Lula administration. “Embrace Marajó had a religious arm here, which was the Pentecostal Churches, the Assembly of God. The people appointed to coordinate the program in Marajó were all pastors,” says Professor Zairo Benjó, a former member of the Pentecostal church. “All the churches here have a candidate for council member. It’s dominion theology [a strategy for spreading Evangelical churches]. If Marajó belongs to the Lord Jesus, its council member has to be a pastor,” he says. Magali Cunha, the researcher at the Institute on Religion Studies, agrees: “Far beyond religion, these are personal, political and financial interests of groups who are instrumentalizing religion, who see religion as a corporation,” she explains. This appearance of parliamentary amendments, with checks, with an electoral purpose, fits this scenario of instrumentalizing religion for political, economic, and financial goals.

According to the researcher, far-right Evangelical politicians, including former-First Lady Michelle Bolsonaro, have recently begun to speak more frequently about protecting women against violence, using a rationale whereby “protecting the traditional family means protecting women.” “It’s the politicians who prioritize this, looking for women’s votes, without getting to the bottom of the structures, preaching punishment for the aggressor. In the churches, the theme of protecting women isn’t a priority. To the contrary. In the churches, the prevailing discourse is of forgiveness at all costs, of ‘having to take it;’ a woman has to stand firm, she can never let her break the marital bond,” says Magali Cunha. “Pentecostal traditions, like the Assembly of God, are churches with deep roots in the tradition of the male universe, of the pastor.” Cunha feels that while Evangelical politicians embrace the idea of protecting women, they end up feeding the monster they claim to loathe. “With this sexist culture, violence is reinforced, because violence isn’t just physical, it manifests symbolically,” she warns.

Former First Lady Michelle Bolsonaro is one of the people advocating for a “traditional family,” but children are generally abused at home. Photo: Nelson Almeira/AFP

The danger from within

At 8:19 on a muggy Monday evening in August, children were running through the hallways of the Assembly of God church in Breves. It was a day for worship. Upstairs, the sound of a keyboard spread through the giant hall, decked out with LED lights and eight air conditioners. At least 500 people were seated in the audience. This unit belongs to the Interstate Convention of Evangelical Assembly of God Ministers and Churches in Pará, of which Senator Zequinha Marinho is a member and pastor. “Jesus said: ‘If you all don’t forgive men of our offenses, the heavenly father shall also not forgive your offenses!’” a pastor shouted from the pulpit. A lady with her eyes closed yelled: “Hallelujah!” A 4-year-old wearing a miniature suit looks at me, hand outstretched and says: “Peace be with you.” Men are on one side, women on the other. The pastor leading the service extends his apologies, but the president of the Assembly of God in Breves, Pastor Marcone Oliveira, couldn’t come because he had to fly to Brasília, where he is attending a meeting in the National Congress.

In Marajó, “protecting family” sometimes means keeping quiet, which invariably ends in trauma and tragedy, according to those working on the frontlines providing care in the region. “People ignore [sexual harassment by pastors] because they’re afraid of sullying the image of the church, of the pastor,” says Iranilda Ferreira, with the Children’s Ministry in Bagre, another of Marajó’s cities. This year, she is running for deputy mayor in the municipality, as a Cidadania party candidate. According to the Annual Report on Brazilian Public Safety, 65.1% of the rapes of minors under age 14 in Brazil happen in the home and are perpetrated by a family member. It is no different in Marajó.

Children and adolescents are less at risk of the sexual trafficking Damares is claiming occurs than they are to be assaulted in their own houses, the family home defended by Evangelicals like her.

In recent years, Evangelical churches have begun popping up along the streets of Marajó Island

In Melgaço, 29 kilometers from worship services, where 29% of live births in 2023 were to mothers aged 19 and under, M.C., 34, weeps. “Monstrosity” is the word she uses to describe her past. She lives in the Tucumã neighborhood — where archeological sites with ceramics made during the time of the Amazonian chiefdoms are buried under homes and trash. She tells of how her father, her grandfather, and her brothers-in-law routinely raped and abused her, her sisters, and her nieces for years. On the banks of the Anapu River, in Melgaço’s hinterlands, there was nobody to ask for help. Her mother had been through the same violence and was silenced by her alcoholic and aggressive husband. “There are five sisters, we were all abused. I feel a very profound hurt. I watched my sisters being victimized and I was a child and couldn’t do anything. I have nightmares,” M.C. says. At 12 she managed to run away. “To [avoid] subjecting myself to being my father’s female, I preferred finding someone who could support me.” She found a man 30 years older. Today, they still live together with 14 kids and adults. They are M.C’s cousins, sisters, daughters, and nieces, many of whom are the result of abuse. Many of them were also abused. Nine have a rare genetic disease called cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis, causing tumors to form on their bodies.

“I can’t say who is the father of whom. I just know that one had a daughter with her grandfather, father, and cousin. Another had a kid with her uncle, brother…,” M.C. says. “None of the kids have their dad’s name on their birth certificate, because none of them know who the dad is.” She says the family was very poor, they all slept together in hammocks in a 20-meter-square shack, every night, isolated in Marajó, which facilitated the rapes. “My father kept my sisters as if they were his,” Maria says. “My grandfather seemed like a normal grandfather, but then I found out… The monster is there, dressed in a grandfather’s cloak.” She says that according to the doctors, the intrafamilial sexual relations increased the family’s risk for developing genetic abnormalities.

Some are born blind, with congenital cataracts, and were only able to see after operating in 2017. Her niece L., 18, weighed just 18 kilos because of the xanthomatosis. Her cousins E. and J. have tumors on their heels. M.L. and A.F. have brain, uterus, heart, and liver tumors. “They have chronic diarrhea, delayed mental development, they need constant medication. If they don’t get it, they become aggressive,” says M.C.

M.C.’s sisters, who have a genetic disease that gives them tumors on their feet, were the product of rapes within her family

Every month, she takes a 14-hour boat ride to Belém to keep up with medical treatments. Her two cousins, 40-year-old E. and 30-year-old J., are terminally ill. “They hang up clothes, tidy up the house, but they don’t understand what this means,” M.C. shares. She says there is a drug that can prevent the tumors, but it has yet to be approved by Brazil’s health agency. Maria is appealing to the courts.

Because of her family’s trauma, she says, out of her six brothers, one committed suicide at 19. Another is addicted to crack. A third is locked up. M.C. holds a baby on her lap, the result of the latest rape in the family. At the start of the year, a mason she hired to build a cistern came early one day and raped one of Maria’s disabled cousins while nobody was home.

In late May, shortly before Bolsonaroist congress members visited Melgaço, another one of M.C.’s sisters came from Portel, where she lives, and gave her baby to M.C. She then left in silence. The child was crying. “Give him a bath quick, he’s probably hot,” M.C. said to one of her sisters. She then went over to the baby. Once she removed the diaper, she saw. “When I looked…,” she recalls. Her brother-in-law, she said, had raped a four-month-old baby, his own child, while another daughter, aged 7, had also been being raped for some time by her father and grandfather, both alcoholics. Noted in the forensic medical exam was: “Breast feeding, 4 months old, red vaginal area with presence of rashes.” The man is being investigated, but he hasn’t been arrested because the children’s mother decided not to press charges. She still lives with the abuser, who every once in a while posts pictures to social media in a hammock with the 7-year-old.

Another one of M.C.’s sisters came one day and said: “M.C., sis, come get my daughter, he ripped her up completely,” she says. M.C. immediately took a motorboat to her sister’s house. Arriving there, she asked for the child. The two alleged abusers were there, one was lying in the hammock. M.C.’s mother, her voice weak, came to the door: “My daughter, take her to the hospital, take her.” “Mother, I don’t believe it, you let this happen with the girls again?” She said: “My daughter, it’s not me. It’s not me. Take them, because I’ll die in this situation.”

The cases were reported to the city’s Child Protection Services, which called on the police and the state Public Prosecutor’s Office — but as M.C. tells it, none of the abusers has ever been arrested.

M.C. welcomed various children into her home who were the victims of rape in her own family, including a baby

In March, another sex crime devastated Maria. Vanessa, her 14-year-old neighbor, was found dead inside of a well, just a few meters away. The crime shocked the city. She used to come to see M.C.: “Auntie, let me live with you?” she would say. “My girl, there’s no way,” M.C. recalls. “Auntie, I’m going to be a ballerina.”

The week the 4-month-old baby was raped, an attorney for Zequinha Marinho who was in the senator’s entourage during the visit to the city came to see Maria in Melgaço. He wanted to get a record of the case. He made a video of Maria telling her story. He also went to Melgaço’s Child Protective Council, a decrepit building located on one of the city’s dusty streets, asking for reports. After publicizing the case on social media, he never showed up again.

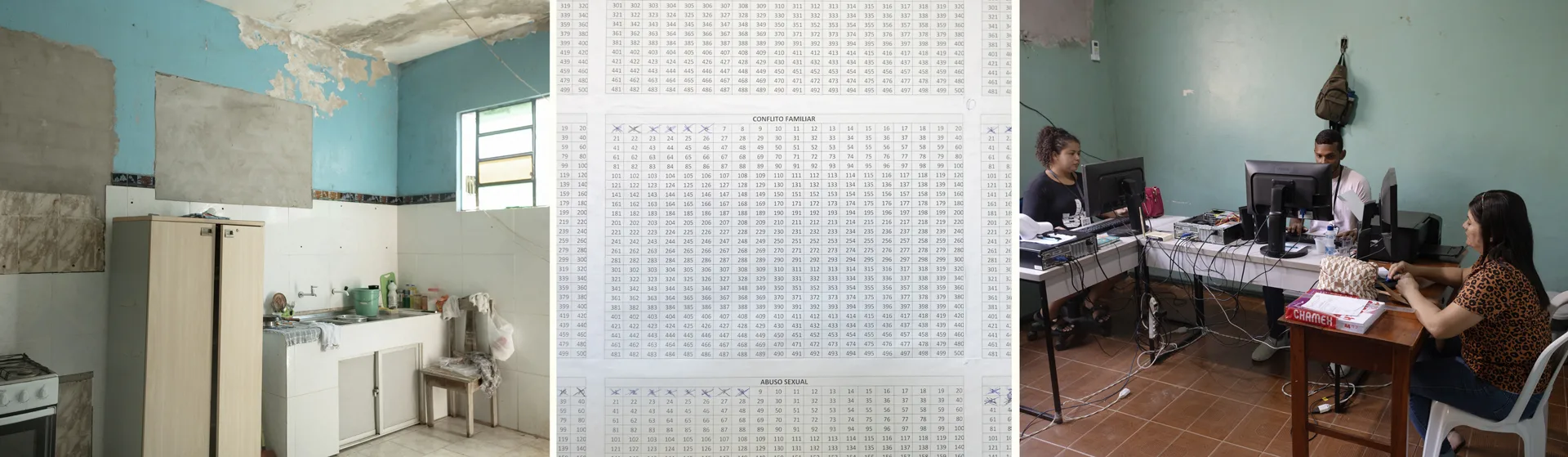

While the senator hands out money from amendments to pastors at an event aimed at combating child sexual violence, the workers at the Child Protective Council use 15-year-old computers, one of them is left open on a desk with no cover to protect its innards, because an employee at the office knows they’re going to have to fix it at any moment. Plaster is peeling off the walls. Four rooms are unusable because of mold and dirt. There is no technical support, nor a toilet that flushes. The lack of adequate structure means workers aren’t even able to enter information into the Childhood and Adolescence Information System. A mother walks through the door to the office, concerned. She came to report that her 13-year-old daughter was taken by a friend to work as a prostitute in Breves. Their fares to travel, R$ 25 (4,5 dollars), were paid by recruiters. But the Wi-Fi doesn’t work well enough for Adimilson Chaves, who works in the office, to communicate with the neighboring Child Protective Council office over WhatsApp.

Melgaço’s Child Protective Council, which receives reports of violence against children, has little power to act, since it is lacking the structure to work

“There’s no boat, this is our biggest difficulty,” he says. “We aren’t doing our job because we have no support. We know about cases of sexual exploration in nightclubs, but we have no way to investigate because we have no transportation.” Adimilson says that when another agency lends them a boat, the tank is empty. And vice versa. The federal government has promised, but has yet to deliver motorboats to Melgaço. Other cities have received vessels (that, still inoperable, are in the “document approval” phase, according to the federal government), which were reallocated from the Itaipu power plant. Asked for comment, the Human Rights and Citizenship Ministry said the municipality of Melgaço will receive the boats in 2024.

In front of the Child Protective Council building is a new car that was sent by Pará’s government, its tank empty for four days. The municipal government is responsible for buying fuel. The workers use their own motorcycles to work. “Our maintenance requests are ignored,” says Cicléa Guimarães, who also works for the city’s Child Protective Council. Asked for comment, the municipality’s Office of the Social Assistance Secretary said nothing about the problems facing the Child Protective Council.

While Cicléa is talking, the sounds of fireworks from an electoral campaign can be heard through the window. Despite all the racket, Marajó, the poster-child for extreme-right politics that exploit the image of vulnerable boys and girls, continues — and possibly will continue — not to protect its children.

While politicians make speeches filled with lies, the children of Marajó continue to suffer various rights violations without effective help from the government

Update: This story was changed at 17:00 on September 25 to add a statement from Minister André Mendonça

Report and text: Bruno Abbud

Editing: Talita Bedinelli

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

English translation: Sarah J. Johnson

Spanish translation: Meritxell Almarza

Copyediting and finishing: Natália Chagas

Editorial workflow coordination: Viviane Zandonadi

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum