“She’s not going to be one of them, she’s going to be there on loan from us.” That was what an artisanal fisher said to the national Secretary of Traditional Peoples and Communities and Sustainable Rural Development, who had recently taken office and who would, starting in those early months of 2023, be tasked with passing along the demands of traditional peoples and communities in Brazil.

When she took office as the environment and climate change minister, Marina Silva called a black woman of the forest, like herself, to take part in the ceremony. It was Edel Nazaré Santiago de Moraes. Upon being introduced at the ceremony, Marina’s guest stood up from her chair and raised the flag of the National Council of Extractivist Populations (CNS) up to eye level.

Nine days later, Marina announced the appointment of Edel, 44, to the top position at the National Department of Traditional Peoples and Communities and Sustainable Rural Development. “The minister is that black woman who got where she is and is pulling others up,” says Edel.

The daughter of Seu Dudu and Dona Miracélia was born in the agroextractivist settlement of Curralinho, located in the Marajó archipelago of Pará. At nine years old, she moved to Pará’s capital, Belém. She worked as a nanny and as a domestic worker, but, looking back today, she sees herself as a “domestic slave,” since she was working in exchange for schooling. After a long stay in the city, trying to gain an education, Edel returned to Curralinho in 2000 and started to get involved with the social movement advocating for land regularization and access to education for traditional peoples. In 2012, Edel joined the coordinators of the National Council of Extractivist Populations, an organization created in 1985, in Brasília, through a movement led by rubber tapper and political leader Chico Mendes, who would be murdered in 1988. Edel was the first woman to join the council as a coordinator and in 2015 she was given another term.

One of her first actions as a department head in the Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (Workers’ Party) administration was to monitor and request protective measures for colleagues who had been violently attacked in April at the extractivist council’s regional office in Belém. Armed men broke into the building, beating and torturing the institution’s members and taking documents and equipment from the office. The criminals also threatened to kill the organization’s members and ordered them to stop making reports in relation to matters of misappropriations of public lands. The Federal Police are investigating the incident.

Her first achievement as secretary was the resumption of the Bolsa Verde program, announced by Lula on World Environment Day (June 5). This is the first seed sprouting from the reforestation that Edel has already begun to implement in the ministry. Every three months, the program gives R$ 600 to families in traditional communities who are living in socially fragile situations and in areas where environmental conservation is a priority. The proposal encourages nature-protecting practices and should benefit 30,000 to 40,000 families. Edel says she is in a hurry and wants public health and education policies to reach Conservation Units and Extractive Reserves, as well as all territories with traditional communities.

“Reforestation also means watering, organizing,” she explains. As soon as she took office, she returned a photograph of Chico Mendes, removed four years ago, to the spot where it had been, over the department chair. By order of Ricardo Salles, the previous department head during the Bolsonaro administration, the rubber tapper’s image was prohibited in every area of the department. Now his picture is back on the walls, and in the hallways, the words “traditional community,” “Indigenous,” “agroecology,” and “gender” are starting to be voiced again – words that were forbidden during the last administration.

Edel Moraes returned a portrait of Chico Mendes to the wall that had been prohibited under former Bolsonaro minister Ricardo Salles. Photo: Fernando Martinho/SUMAÚMA

On another wall of the department’s offices, Edel has hung a cloth panel that says “Peoples of the forests, of the fields, and of the waters take office.” Everyone who comes through the department’s doors is invited to sign it. The wall hanging was a present from her colleagues at the University of Brasília. The first to sign was federal Deputy Célia Xakriabá (Socialism and Liberty Party for the state of Minas Gerais), her classmate while she was studying for her master’s and the person who she also shared room and board with in Brasília. When writing their dissertations, they both looked to the women in their native territories for knowledge on fighting for the earth. Both listened to the ancestral wisdom of their peoples.

Edel asks for credit and for patience from traditional communities, because the Bolsonaro administration brought intense and immense devastation and she recognizes the ambiguities in the Lula administration. “I don’t think that the government has a magic formula to do everything I’d like to do in such a short time.”

In August 2023, after speaking with SUMAÚMA, Edel was surprised by the brutal murder in Bahia of Maria Bernadete Pacífico Moreira, a leader in the quilombola community and in the community of traditional African peoples. In a message shared with our reporters, she said that Mãe Bernadete’s murder by gunfire within her own home “exposes the violence against black women and leaders on the vanguard of implementing policies to build a just and more democratic country.” Edel reiterated the need for “rapid investigation into why” this leader died.

Making traditional communities stronger depends on territorial and environmental management and on getting territories in good legal standing, according to Edel. The Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics began to release 2022 Census data in late July of this year. In Brazil, there are 1,327,802 quilombolas, as members of Maroon communities are known in the country, living in 1,696 municipalities. Over 87% of them live outside of formally demarcated and recognized areas, while just 4.3% of the quilombola population resides in deeded territories.

In this interview, granted exclusively to SUMAÚMA at the department’s offices in Brasília, Edel Moraes assesses the scope of the minister of Indigenous Peoples, Sonia Guajajara. In Edel’s estimation, Guajajara’s success and high profile means we can dream about a Brazil with a Ministry of Traditional Communities. “I am one, but I’m not alone,” she emphasizes. Read the highlights from our interview below.

SUMAÚMA: What does this collective instrument of investiture, with its many signatures, mean to you?

EDEL MORAES: I come from a place where the struggle is not solitary. It is collective. I am the fruit of a history of fighting for collective rights. Paraphrasing other people who have already said this before me: I am one, but I’m not alone. It’s like the song says, I am a village. Before, I used to say that I was a lonely village. Not today. I go back home. I have a loving husband, who takes care of me. But before I was sort of this lonely village.

Now I’m a voice that is here today in Brasília, within the department, but I am the responsibility of all of these voices that can be represented here [the names on the instrument of investiture], of many of these, and especially of those unable to come here. I feel that I am this voice: because I’m someone from there, I’m the daughter of Seu Dudu and Dona Miracélia who are there, in the Amazon, within the community, in the territory. I come from a collective struggle, which originally is the National Council of Rubber Tappers. I come from the Basic Ecclesial Communities [BECs, in the Catholic church, emerging from the Liberation Theology movement of the 1970s], I come from a territory where we’ve always lived as a community, as a collective, as relatives, as neighbors, as a mutual aid group in this experience of life. I come from a place where solidarity was provided in mutual aid, in the neighborhood, with comrades and friends. My classmates from my professional master’s degree course brought this instrument of investiture here. This collective came here to tell me that I wouldn’t be alone.

One of the first messages I received, when I was invited and announced that I would be in this space, was from a relative who is a fisherwoman. And she said this: “One of us was called up and has our authorization to go. She’s not going to be one of them, she’s going to be there on loan from us.” This Department of Traditional Peoples and Communities is a space of resistance, a space of achievement for traditional peoples and communities. We waited for over 500 years of history to have the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples. They are celebrating and we are celebrating with them. We, from other traditional communities, also wanted space. And in the transition, this space [the department] was built. To my surprise, I was later invited by our minister, Marina Silva, to be here, for which I am deeply honored. I received it not as an invitation, but as a call. There are things that you just can’t refuse, knowing my place as a black woman of the forest, an Afro-Indigenous woman, a cabocla [an individual of mixed European and Indigenous ethnicity] woman, a woman from the [traditional] ribeirinha community, and so many other identities. My whole life has been based on the fight for policy. Before, I was just at the door, waiting to come in and offer proposals. Being here, receiving demands from my own and our own, and being an instrument to help in this formulation along with another woman, whose story is very similar to mine, this is a calling.

The Department of Traditional Communities, the Ministry of Environment and Climate Change, and the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples have put these people in leading positions and have given these communities hope, especially after the violence of the Bolsonaro administration. What do you see as a priority, in this scenario that comes after the devastation of life and biomes?

First, it’s being aware that we are not, at this time, the solution to everything. Yet I consider it the great stalemate of the moment. This destruction was being waged inside of here. Right now, we are reforesting the ministry, in every sense. This here was completely destroyed and demobilized with the socioenvironmental agenda [of the previous administration]. The words “traditional community,” “Indigenous,” “agroecology,” and “gender” were forbidden in this department. There was violence of all kinds in denying our rights as traditional communities. There was violence against the public servants who stayed here in silence. There was an attempt to erase this history. So the priority is reforestation of the ministry, reforestation of hope, with work and with action. We must rebuild. It’s reforesting by reorganizing all of this. There are many priorities. The ministry and the government are committed to zero deforestation in the Amazon. Committing to zero deforestation is a huge responsibility. Having the name “Ministry of Environment and Climate Change” in its new format is a very big challenge, because now it is no longer a threat: climate change is there, galloping ahead, it’s already happening. Deforestation is out of control. There is no way for us not to look first and foremost at the territories already demarcated and those not demarcated with this concern: we need to guarantee the continued sustainability of these things we’ve already achieved, and of what was a main target for dismantling and threats [under the Bolsonaro administration].

Without territory, there is no life for peoples and communities. The fight for territory is part of the fight for the human, environmental, and social rights of those living there.

Edel gave a collective instrument of investiture, signed by representatives from various traditional communities, a prominent place in her office. Photo: Fernando Martinho/SUMAÚMA

When Minister Marina Silva returned to the Environment [Ministry], what had been totally deforested within these institutional spaces, following the Bolsonaro administration?

It was total deforestation here, it was total destruction of the agenda. First they guaranteed that not one inch of land was demarcated, discussed. Second, these government officials did not work on the agenda. Within the ministry, there used to be a Department of Extractivism, there was the PNGATI (National Policy on Territorial and Environmental Management of Indigenous Lands) and various other actions and departments. These departments were all demobilized to other ministries, with other configurations. What remained here, remained with nothing. One example: the Bolsa Verde program. There was not one payment over the last five years. This is the first seed that we are starting to water, the return of the Bolsa Verde program under a new configuration. This is the first seed sprouting in this reforestation. The perspective is for us to develop different actions in territories, using young people in this process, dealing with social technologies to supply water, like cleaning the Amazon, doing productive and social organization of communities. What we want is the promotion and social inclusion of these families, and not an eternally-held idea that those who conserve [nature] are poor people, or have no money, or are in extreme poverty. With Bolsa Verde, we want to cover as many Conservation Units as we can in this initial moment, reaching sixty-six. Agroextractivist settlements, territories belonging to quilombolas, and Indigenous peoples in conservation areas are eligible too. We want to reach 30,000, 40,000 families benefited.

Brazil and the world now recognize the original peoples’ rights, and this historical liability [with traditional communities]. Yet Brazil should also know about traditional peoples and communities in a much broader sense, considering this great pluridiversity. We have to recognize the rights of peoples and communities in the territories that are already demarcated, and provide support in structuring these places and making them effective.

What am I proposing as something new from our department: many groups do not yet have territories. Like the retireiros [traditional community of free range cattle ranchers] of the Araguaia River. Either we find a solution to guarantee territory for the retireiros of the Araguaia River or this is an identity that we lose in our country. Our collective identities are related to collective territorialities.

Drinking from the fountain of the Indigenous peoples’ territories, Chico Mendes started a revolution in the world, which is the collective territories, the settlements, the extractive reserves, and all the other modalities that come along with this. We have an immense challenge with agroextractivist settlements today in Brazil, for them to be recognized as areas of environmental importance in the world. My community’s settlement is no different from the extractive reserve right next to my community. We are all related in this territory. And so it’s no use protecting one community and the other is not inside of this protective framework.

This is what combatting land-grabbing [theft of public lands] will be: fighting to guarantee the effectiveness of the territories already created, the creation of those not created, and the removal of unlawful intruders. We need to resolve problems on extractive reserves and find a solution along with the government to guarantee these communities’ rights within these territories. We have the Extractive Reserves in Marajó, Mapuá, and Terra Grande Pracuúba… There are CAR [the national environmental registry of rural properties, a self-declaration of land ownership] registrations on top; they have to be removed from Extractive Reserves, because this is an extractive reserve. Our responsibility lies in supporting these actions and the rights of the peoples and communities.

Our department has to formulate concrete actions. We have no more time, as a community, to sit around thinking about diagnoses, reports, pretty little pictures. We need public policy reaching the tip, connectivity, internet, social technologies, water to drink. We need a contextualized school. Our mission is to be provocateurs and proposers within another view into these territories.

We put them in a single package, thinking that the Amazon only has one kind of community. We are diverse, we are plural. I have a political identity. I am a black woman of the forest, I am an extractivist woman. This is a political identity built by the right for us to have rights. I am an Afro-descendent, I am the result of black, Indigenous and other diasporas’ ancestry. The right was not taken from me, during this epistemicidal process, to say who I am. We are retaking our identities. I always challenge those who create stereotypes to get to know our communities.

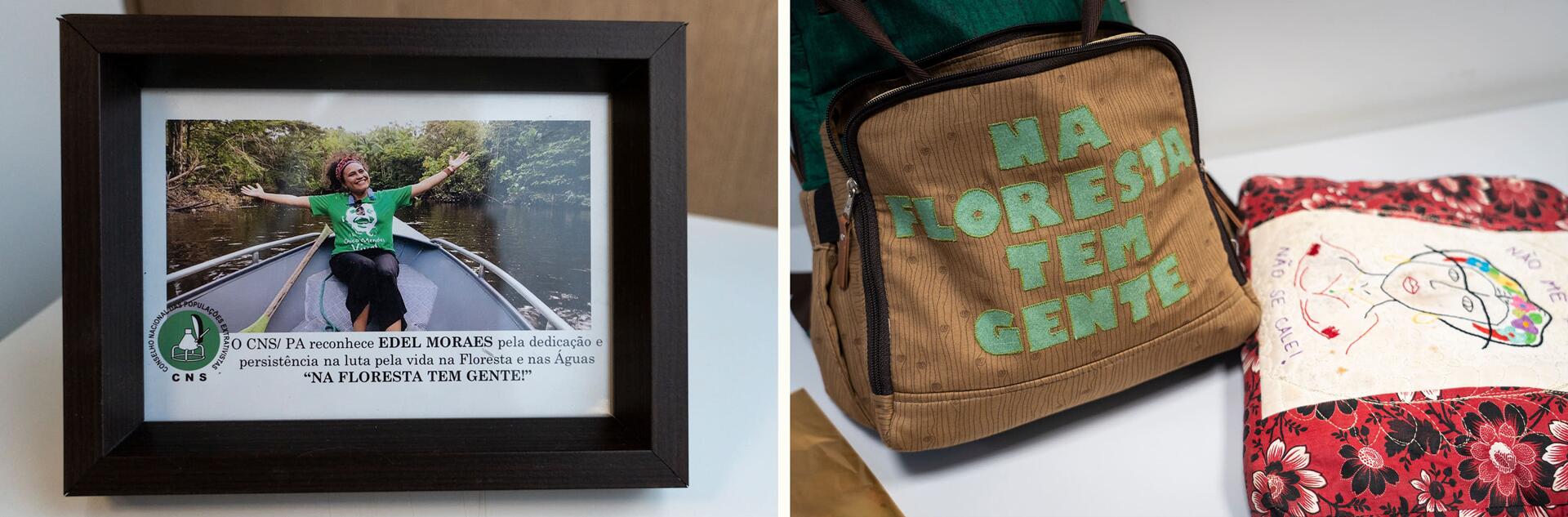

Edel Moraes in her days as a member of the National Council of Extractive Populations. On the right, a detail of the secretary’s bag. Photo: Fernando Martinho/SUMAÚMA

How can this process of getting to know traditional communities be more educational within Brazil, to reduce stereotypes and prejudices?

First we have to have more people learning and understanding. I am a big believer in education. Just as we moved toward guaranteeing the inclusion of the original Indigenous peoples and quilombolas, we must also guarantee that other communities are brought in to participate. I’m the fruit of a master’s program that was designed for traditional peoples and communities, I’m also the fruit of a process of forming resistance at universities. Misrule got itself elected using social media. How is it that we are unable to use social media for good, to provide visibility [to traditional communities and peoples]? Part of the visibility we have today of Indigenous people was because they also knew how to use social media, to empower the [Indigenous] youth. I see major action connected to education, which institutionally we can call Environmental Education.

We listen with great honor to the story of Chico Mendes, but Chico Mendes isn’t the only one who exists in the Amazon and in Brazil. Where are all of the stories of all of the heroes and heroines who fought to create the sixty-six extractive reserves? Where are these stories recorded and developed within the academic curriculum, in a transversal manner? I’m dealing with this in an ethnodevelopment project, traditional peoples and communities and collective territories. Today we find municipalities where nearly half is settlement, one part is extractive reserve, and another part is quilombola – and there is no municipal awareness that it is a huge green territory. And then programs come from top to bottom that include completely deforested municipalities as if they were green municipalities. We have to turn this game around.

Before accepting the invitation to join this government, you invited Célia Xakriabá (currently a lower house member) and Sonia Guajajara (currently a minister) over for lunch at your house. Did you make plans that day to work in an integrated way, on mysteries and in Congress?

That day was a meeting of girls and women, where I wanted to have a lunch for my friends for life, because, as I’ve already mentioned, we don’t have one minute of peaceful quiet. On that day they didn’t even let us make plans. One thing that the world needs to know is that we are people, women. That day I was even weaving a necklace for Sonia.

Of course my eyes are not green enough and Sonia and Célia were not just there because they like my food. It’s always articulation. Our stories intersect, including because of the emergence of the Alliance of Forest Peoples movement. Sonia and I re-signed the letter of the Alliance of Forest Peoples [created in 1987, the Alliance picked back up in 2020, in a movement led by Angela Mendes and Cacique Raoni, which was supported by leaders like Sonia Guajajara].

A successful Ministry of Indigenous Peoples is a gigantic step and is payment on Brazil’s historical debt to the original peoples. It is an immense mirror for us to dream of one day having our Ministry of Traditional Communities. It’s a source of hope in practice. Célia and I did our master’s degrees together, we shared meals, a place to sleep. We got lost together, because we didn’t know how to get around the city. We discovered Brasília together. We connected for the struggle.

Sônia Guajajara, Claudelice Santos, Angela Mendes, and I wrote an article entitled Amazonian Women in Defense of Life. It was a response to former Minister Ricardo Sales, who had asked who Chico Mendes was, what Chico Mendes’ story was, and he said that nobody knew. Now we’re going to show who Sônia Guajajara, the minister, is, who Edel, the secretary of traditional communities, is. See there, that Chico Mendes’ picture is back? His photograph was also prohibited from staying here. Our connection is one of institutional and governmental responsibility. It is our responsibility to make ourselves stronger. The success of Minister Sonia is our success as traditional communities.

I’m happy that I’m not the first to occupy this space. The first was Minister Marina Silva, she is the pioneer. The minister is that black woman who got where she is and is pulling others up. She wants us to have visibility, she wants us to be able to work. And she holds us to this.

You mentioned the importance of the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples. President Lula did not demarcate all of the Indigenous lands that the Indigenous movement expected. How do you see the ambiguities within this government?

Picking up again and reforesting take time, because the destruction was very fast, considering a margin of six years [four years of the Bolsonaro administration and two under the Temer administration]. The destruction goes further back, but in those six years it was intense. Reforestation also means watering, organizing. I don’t think that the government has a magic formula to do everything I’d like to do in such a short time. The government should have time in the bank to do things.

The Ministry of Indigenous Peoples is being built now. Between building and providing a response for all of the actions, it’s humanly impossible in such a short time. The Ministry of Environment is being totally reconstructed and reformulated, and with many agendas. Here we haven’t even received or found any documents.

But I believe that this resumption is a great start. Everyone here has the same energy and the same strength to do things. I’m forty-four years old. My parents were born and raised in my community. To this day not many things have made it there. Yet my dad, with nine kids, has one studying for their doctorate now. This only began with the first term of the Lula administration, when I was able to enter a university. None of my ancestors had this. I’m the one in a hurry here, because policy still hasn’t arrived to ensure health care and quality care for my father and mother, who only have 30% of their sight due to glaucoma and to a malaria fever for which they did not receive adequate care. I’m the one in a hurry, because I didn’t see my child grow up and now I’m here in charge of a department. So we are in a hurry to have everything that was taken from us and denied to us, but there is the challenge of overcoming bureaucracy. We’re in a hurry for everything. But it won’t be during the administration’s first months that there will be answers for everything. We’ve advanced a lot and we need to account for this.

It’s legitimate and I believe that the movement should indeed not be content so as not to allow the government to get comfortable. I’m not afraid of this place and I expect to be held to account. Energies, forces, actions, and projects are being resumed. I am in dialog with bioeconomy department colleagues, who are paying attention to building organization of the bioeconomy agenda, of the socio-biodiversity agenda. I am in dialog with colleagues who are building the climate change agenda, transversally. More than fifteen ministries, through the efforts of Minister Marina, have undertaken this climate change agenda. That is no small number. It’s the first time ever that we are hearing all of the ministers wanting the environment agenda. There is no way to escape frustration. But there is lots of commitment.

Spell check (Portuguese): Elvira Gago

Translation into Spanish: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Sarah J. Johnson

Photography editing: Lela Beltrão

Page setup: Érica Saboya

The green and yellow co-opted by the extreme right are taking on new symbolism in creating the Office of the National Secretary of Traditional Peoples and Communities. Photo: Fernando Martinho/SUMAÚMA