For the Guaraní people, yerba mate is the mother plant, the most sacred, but in Paraguay, the birthplace of the most popular non-alcoholic beverage in the Southern Cone, finding it can be an odyssey and consuming it, a pleasure and an act of resistance

One day twenty years ago, around a fire, Victoria told her husband Ernesto that she would no longer drink yerba maté

It is not yet four o’clock in the morning in Tekoha Y’apy (meaning Land of the Spring in Guaraní), a village in northern Paraguay less than 125 miles (200 kilometers) from the Brazilian border, when an old man nimbly emerges from an unpainted brick house. It is October 2022, southern spring, but it is cold. There is a smell of damp earth and fresh mint and sage leaves. Ernesto Vera, the name of the early riser, wears a gray coat a couple of sizes too big for his 5’6” (1.6 m) frame, and his hood reveals only a fringe of black hair, broad nose and round cheekbones. The tamoi (spiritual leader in Guaraní) walks over small twigs so wet that they do not rustle when he steps on them. After entering the oga guasu, the large communal house, a rectangular construction with a straw roof, he squats down and lights a fire with matches where he boils water in a battered pot. His eyes and hands radiate a color similar to the earth beneath his sandals. As the water reaches the point just before boiling, Ernesto Vera puts the ground yerba mate into a hollow, sculpted gourd, then adds the hot water and, taking it with both hands, sips it through a wooden cane, a thin reed or tacuara (bamboo pipe). There is not a day, “if there’s time,” he remarks, that goes by without drinking maté. When he offers the yerba to his wife Victoria, it is dawn. Also sitting around the fire are two of his daughters and two granddaughters. The morning chirping of birds accompanies the family’s singing and drumming.

The Guaraní have been performing similar ceremonies in these tropical lands, the cradle of yerba maté, for at least a thousand years, according to some authors such as the Argentine Pau Navajas (Caá Porã. El Espíritu de la yerba maté, 2013). European scholars named yerba mate ‘ilex paraguariensis’. Although more well-known in the rest of the world because of Lionel Messi or Pope Francis, it has been part of the Guaraní identity since this indigenous people and their language Tupi-Guaraní spread across the American rivers —from the Amazon jungles to the Caribbean (Panama is a Tupi word) or the Yguasu (giant water) falls— and remains so today, when some two hundred and twenty five thousand people spread between Brazil (sixty thousand), Paraguay (sixty thousand), Argentina (twenty five thousand) and Bolivia (eight thousand) make up this stateless nation of people.

Ernesto Vera in front of the big tatuape, an oven made of branches shaped like an armadillo’s skeleton, where he dries hundreds of pounds of yerba maté over the flames

All plants are sacred to the Guaraní: there are ceremonies for corn (avatikyry) and for new plants (ñemongarai), but yerba maté, ka’a, is the most sacred of all, the tamoi explains. It is considered the mother plant. The most ancient way of using it was to put it in your mouth, chew with your teeth and drink water from the river with your hands. This is enough to taste its flavor and feel its stimulating properties. In important rituals, such as the pyahu (new) year or the mitakarai (the ceremony of the Avá-Guaraní people to give the spiritual name to each young person in the community), yerba mate should be drunk to purify oneself, to prepare oneself, to be stronger, healthier and connected to the earth. And yet, one day twenty years ago, almost at the same time of the morning and around a fire in the same place as we sit now, Victoria, school teacher and caretaker of the children and tended the garden, told her husband Ernesto that she would no longer drink yerba maté.

‘Mba’e (what)? What harm can ka’a do to you?’ Ernesto asked her in Guaraní.

‘I think it upsets my stomach. Every time I drink it, I get heartburn.’

‘E’a!’ Ernesto exclaimed in surprise.

Victoria, a soft-spoken woman with long, dark hair tied back in a bun, usually looks down at the floor when she responds to the father of her four children, but that day, Ernesto says, she looked right at him when she spoke.

Ernesto was shocked, but Victoria’s words made him reflect: it had been about twenty years since they had stopped drinking ka’aite, the authentic yerba maté, in its wild form. As it is a forest plant and the forest was decreasing, it became impossible to find. Although an essential plant in the Guaraní diet and their spiritual rituals, it had become almost a luxury. The priority for the people was to plant corn, cassava and beans. To feed the chickens and to work so they themselves could eat: to put up the fences of the ranches of a karaí guasu (great lord), who for less than 100 dollars sends a truck and loads the workers onto it who do not return for another month or perhaps longer; sometimes put to work carrying wood to make charcoal, other times reining in a wild cow escaped from its owner.

Ernesto and Victoria, farmers with almost zero income, would buy yerba mate from a store. They brought it home already ground and wrapped in paper, in the shape of a brick. For more than 20 years they consumed it industrially, from commercial brands that own large yerba mate monocultures and control the lot of small growers. It is the yerba mate companies that collect the leaves, use agrochemicals and speed up the processes breaking with tradition, lowering the price to producers and selling it more cheaply to consumers. Until Victoria’s stomach said enough was enough.

After his wife’s announcement, Ernesto took refuge in the oga guasú, where he sings on this spring morning for us. He prayed and sang to Tupã, one of the greatest Guaraní gods. He smoked his pipe and meditated, fretting about his wife’s health. And so it was, he recalls, that he had an idea: he would search for treasure. He would travel across the large ranches to find the challenging forest where the wild ka’a trees grow. He would bring Victoria the most tender and natural leaves in existence.

***

Bienvenida Vera Ortiz picks a pumpkin: the Avá Guarani families of the Y’apy indigenous community produce vegetables for their self-consumption

In search of a treasure

In Tekoha Y’apy 1,800 farmers preserve 850 hectares of rainforest and live on another 650 hectares that they use for their homes and gardens. A few miles away, three landowners own some 300,000 hectares in the same department, called San Pedro, which they have almost completely deforested. Paraguay is one of the countries with the most unequal land ownership in the world —2 percent of the population owns about 80 percent of the arable land— and 80 percent of the forests are within private properties, mostly large landed estates, or latifundia. Tens of thousands of hectares of fertile land, rivers, mountains, springs and valleys, which could fit several European countries, are in the hands of a single person, such as the Brazilian Tranquilo Favero, the former Paraguayan president Horacio Cartes, or Carlos Casado, a descendant of Argentines and Spaniards, sort of 21st-century feudal lords on lands that belonged to indigenous peoples.

Ernesto Vera’s grandfather had taught him how to find ka’aete, which grew under the sturdy pink-flowered lapacho trees or among the moss-covered yvyra pyta surrounded by giant ferns. They were tall, sturdy trees, up to 50 feet (15 meters) high, which two men could climb at the same time and they would barely move. Yerba maté, Ernesto recalls, grew very close to Tekoha Y’apy. It only took an hour’s walk to reach it, enjoying the scent of orchids and the earth soaked by the stream water, the orchestra of birds, monkeys and crickets.

“They were part of the forest, like the jaguaretés were,” he says.

Jaguareté in Guaraní comes from jaguá, which is what they called the jaguar before the arrival of the Spaniards and their dogs. Since then they added the suffix ‘eté’, which means ‘authentic’.

But when Ernesto set out on his search for ka’aete for Victoria, his community was already an island of dark, lush jungle surrounded by a vast sea of pastures and cattle ranchers’ cows. Since 1950, Paraguay has deforested eight of the nine million hectares of its Upper Paraná Atlantic Forest (BAAPA), the official academy name for this area of subtropical jungle, bush and forest that also extends into Argentina, Uruguay and Brazil. In Paraguay, one of the ten largest beef producers in the world, there are already almost twice as many cows (around 14 million) as there are people.

In his search, Ernesto Vera came across new gates made of palo santo wood leading to the cattle ranches, with more pasture for cows and horses, with new barbed wire fences and even with armed guards. Less and less forest, less ‘monte’, as they call it in Paraguay, although there are no mountains, and more and more noise: the song of the bare-throated bellbird (procnias nudicollis) replaced by the engine of a bulldozer, the roar of the jaguar desecrated by the dull thud of the steel shovel against the base of a hundred-year-old tree, the songs of the cicadas replaced by the endless traffic of cars and motorcycles.

Fernando Vera obtained permission from the owners of this farm to harvest. Many of the native yerba mate forests are now on private properties

“There used to be a lot more things in the forest in general. More types of trees, animals… there was more of everything. More medicinal plants. More fruits. Before the foreigners came. It was very cool in the forest before. The forest disappeared and the heat came,” Ernesto says in Guaraní as we walk around his house with his 19-year-old grandson Fernando, who is about to enter university on a scholarship and who acts as my translator.

For several days in the early 2000s, Ernesto walked across those cattle ranches, dodging new fences and armed guards, until, close to a stream, he found what he was looking for. He climbed the mate tree without looking down, until he had a hundred leaves in his pockets and dozens of whole branches slung over his shoulder.

“Emañami, look, my love. This one won’t hurt you,” he said to Victoria, placing his bounty proudly on the ground.

They dried it over a fire, stored it for a few days, ground it and then tasted it. There it was: the true flavor, which lingers on the palate, smoked leaf, green, sweet and bitter at the same time. The flavor remained even after many rounds. When Victoria drank Ernesto’s yerba, she no longer suffered from heartburn.

This one won’t hurt you, my love

Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay each celebrate their National Mate Day on different dates, and Paraguay has another day for tereré, the same yerba drunk cold but with the same passion. In each of these countries there are more than 200 different brands: with or without a straw, more ground or less, with mint or with stevia, with lemon or plain… Mate remains the most consumed non-alcoholic beverage in Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, Chile and southern Brazil. Each Uruguayan —they drink the most, more than Argentines— consumes about 5 pounds (8 kilos) of it a year. As a national symbol, mate is news in the media and a central topic in Sunday debates. The first image that comes to mind for a foreigner who thinks of the Southern Cone is probably that of a soccer player, and the second one is probably that of people walking around with mate thermoses under their arms.

Mate leaves contain caffeine as the psychoactive principle, and xanthines, alkaloids that are also found in coffee and chocolate. It has stimulant, depurative and antioxidant properties. But for the people who live in these countries, it is much more: it is a ceremony. Mate is lovingly, gradually, skilfully brewed; it is imbued with a certain power. Most of the time, people share their thoughts and feelings over a mate or a tereré. This ‘circle of the word’ is still taught today by the Guaraní and almost all the indigenous peoples of America despite the fierce individualism of our times. Even when one drinks it alone, there is a dialogue with oneself: every mate drinker, or matero, remembers the first time he or she consumed it alone, accompanied by his or her thoughts. Drinking mate means using the same leaves of a plant and a little water, for hours. It is not about consuming, not about buying, not about spending compulsively. It is a symbol, a marker. Mate is identity.

Mariano and Fernando Vera make the first toasting of the yerba mate leaves by hand. The next part of the process continues in the tatuape

All of this helps to explain the daily consumption of mate in Syria and Lebanon. After World War I and the fall of the Ottoman Empire, many Middle Easterners came to the Americas to start new lives. They came to love the land and were an integral part of its development. Hundreds of thousands stayed. Those who returned to their countries of origin took the custom of mate with them and passed it on to their children and grandchildren as a symbol and memory of their odyssey. I myself, son of a family of Argentine migrants in Spain, remember my father wondering on the way to the airport in Madrid how much yerba mate the grandparents, uncles or godmother would have brought with them. Me biting my nails next to a suitcase full of packages as if Christmas had come early. My family yelling, crying and laughing, all at the same time, around the maté.

The world is consuming more and more yerba maté. In the United States and Europe it is starting to be found in unusual forms, such as cans of soda or tea bags, in supermarkets. They are sold as a more natural alternative to super-stimulants such as RedBull, but are extremely processed. One example: Club-Mate, the most popular in Europe, is a German drink that has caffeine extracted from maté, 0.4 ounces (10 grams) of sugar in every 11.16 ounces (33 centiliters) in addition to 23 other ingredients. Argentina is the country where it is most produced and exported, with an annual average of 35 thousand tons, the main destinations being Syria (72%), Chile (14%), Lebanon and the United States (2%), according to Argentina’s National Institute of Yerba Mate.

While anyone in the global north need only go to WalMart or Carrefour to consume a mate derivative, Ernesto Vera, tamoi, Guaraní, continued his quest to find the authentic yerba maté, and Victoria’s happiness.

Why relive the trauma?

The Tekoha Y’apy forest was no longer surrounded only by cows. From the first decade of the 2000s onwards, Paraguay became a country of cows and soya. A large part of the pastures were converted into fields of transgenic soybeans, hyper-protein grains that became an indispensable raw material for cattle feed in Europe and China. Soybean fields in Paraguay have grown to occupy some three and a half million hectares, seas of green without a single tree besiege the last indigenous peoples and forests of Paraguay, Brazil and Argentina.

Ernesto’s search for ka’a for Victoria became even more complicated. The tamoi began to explore other communities, to ask where there might be an island of forest where yerba mate would grow. In his walks there was a word that kept coming up: permission. Ernesto Vera had to ask permission from a rancher, permission from one of the families or large companies that owned the land. Permission to open the gate of the ranch without being shot, permission to walk among the cows, permission to hold in his hand a few leaves and branches. Permission to cross the vast soybean fields where a single person on a tractor with a touch screen and air conditioning can harvest hundreds of hectares in an afternoon or spray toxic agrochemicals around his community.

The situation reminded him all too much of what his ancestors had suffered for hundreds of years. European colonizers observed the first consumption of yerba mate in the 16th century in what is now Paraguay and was then the Viceroyalty of Peru. As soon as they saw it, they outlawed it. In 1610 the Inquisition of the Kingdom of Castile prohibited the use of the plant and in Asuncion they imposed penalties of 100 lashes of the whip for the Indians and a fine of 100 pesos for Spaniards who consumed or trafficked yerba maté, according to the Argentine Jerónimo Lagier in his book The Adventures of the Yerba Maté).

Only 20 years later, the Spaniards would legalize it and turn it into the basis of their economic and territorial expansion in the region, giving rise to the ‘Province of Paraquaria’, a kind of Jesuit State that came to include part of Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay and Uruguay, at a time when Spain and Portugal were still dividing up the American territory in treaties. This branch of the Catholic Church, together with the Franciscans and Dominicans, managed diplomatic, military and religious relations with almost all of the Guaraní peoples. For around two centuries they imposed their religion and customs on the indigenous peoples while they assimilated their knowledge, their work force and, not only their yerba maté, but also their lands. Their forests. They were the first Europeans to grow monocultures for export from South America.

“And the great Captain Duiy, who arrived the other day, also in front of us, beat an Indian who had just arrived from Mbaracayú with his own hands, attempting to take him to Mbaracayú,” says a manuscript housed in the National Library of Rio de Janeiro. The document is dated August 25, 1630 and is known thanks to the work of the Spanish Jesuit linguist, Bartomeu Melià.

Torture, murder, starvation, rape, beatings. The same thing was still happening 200 years later. It did not change when the Jesuits were expelled by the Catholic Monarchs, nor when, later, the Spaniards were expelled by the Creoles who declared Paraguay’s Independence. The descendants of the Guaraní, the half-indigenous, half-Spanish, half-Afro-descendant, half-Portuguese peasants continued, under slavery, to produce yerba maté. They were called the mensú, because they supposedly received a monthly salary, although this never happened. A single company, Industrial Paraguaya, owned one of the largest areas of land in Paraguay:

“What you see is no longer a man; he is still a yerba worker. Perhaps there is rebellion and tears in him. Miners have been seen crying with the enormous bundle on their backs. Others, powerless to commit suicide, dream of escape. To think that many are barely teenagers. Their wage is illusory. Criminals can earn money in some prisons. They cannot. They must buy what they eat and the rags they wear from the company.”

This was written in 1909 by Rafael Barrett, a Spanish journalist and anarchist poet who lived in almost all the yerba mate countries, and was thrown out of almost all of them.

The situation has improved nowadays, but the current yerba mate companies pay so little that Paraguayan farmers can only achieve fair payments by joining together in cooperatives. An example of this is the Oñoirũ brand, a model of organic farming production, which benefits and represents many families in the Itapúa Department.

Bienvenida Vera and Daina Ortiz play by a stream. The preservation of nature is essential to the culture of their people. Their territory is surrounded by forests and fresh water

History kept Ernesto Vera, and almost all Guaraní people, distanced from the production of yerba maté. What’s the point of growing ka’a if you can buy it for coins? Why relive the trauma of their parents and grandparents? But tired of searching for a forest that no longer existed, of yerba mate barely growing in places he could count on the fingers of one hand, Ernesto Vera asked himself another question: How long will they give me permission? And then, just like when Victoria told him he would no longer consume maté, Ernesto Vera reflected and had another idea: if he could not go and get the yerba maté, the yerba mate would be grown in the community.

“And thank goodness I did!” exclaims Ernesto now in front of the big tatuape, an oven made of branches shaped like an armadillo’s skeleton, where he dries hundreds of pounds of yerba mate over the flames licking out of a fire pit.

Tired of searching, Ernesto planted and harvested

They met ten years ago during the mitakarai. Ernesto Vera danced to the rhythm that his wife Victoria and other women beat against the ground with hollow tacuara (bamboo) sticks. He moved the mbaraká –maracas– in his hands while chanting a melody that encourages a trance-like state. Norma Ávila, singer and artist, had arrived from Asunción, the capital, and had been invited to join the oga guasu. She let herself be carried away by the music, in communion with the others. A friendship emerged and, to Norma’s surprise, a business relationship.

Ernesto Vera had teamed up with other families who planted their own yerba and kept inviting others to start growing it again. When Norma Vela arrived in Tekoha Y’apy, this and other neighboring communities had accumulated several hundred pounds of yerba. Although the tamoi had the idea of fetching leaves for Victoria and growing the yerba in the community, it was Victoria who came up with the idea of offering the visitor their own yerba production, made the traditional way, and selling it in the capital.

Ernesto and Victoria showed the visitor the process. The Tekoha Y’apy community gathers the branches full of leaves and lights a bonfire to carry out the sapecado, an initial drying process that involves exposing the branches very briefly to the flames until they seem to shriek in chorus as the water in them evaporates. They are then dried out m for several days in the tatuape, a structure about ten feet (three meters) high, carefully tied using rope made from güembé roots —which are also used to make hunting bows—, and without using a single nail or screw. The oven, which Ernesto Vera scales effortlessly, can hold hundreds of kilos of branches and yerba leaves and several people. Just below, a pit dug in the red clay sand houses a fire designed and prepared to last several days. Wood burns there, smoking and slowly cooking the yerba mate leaves. After about three weeks, the manual grinding process begins, in huge mortars made of tree trunks, and when the yerba is ready, it is stored for a year to reach the optimum flavor point.

Ernesto Vera usually rests under the tatuape, a kind of handmade oven made of branches that holds the yerba mate leaves while they roast and exude a mild aroma. Underneath this armadillo skeleton-like structure is the chimney that distributes the heat from an underground fire fuelled by wood harvested from the forest

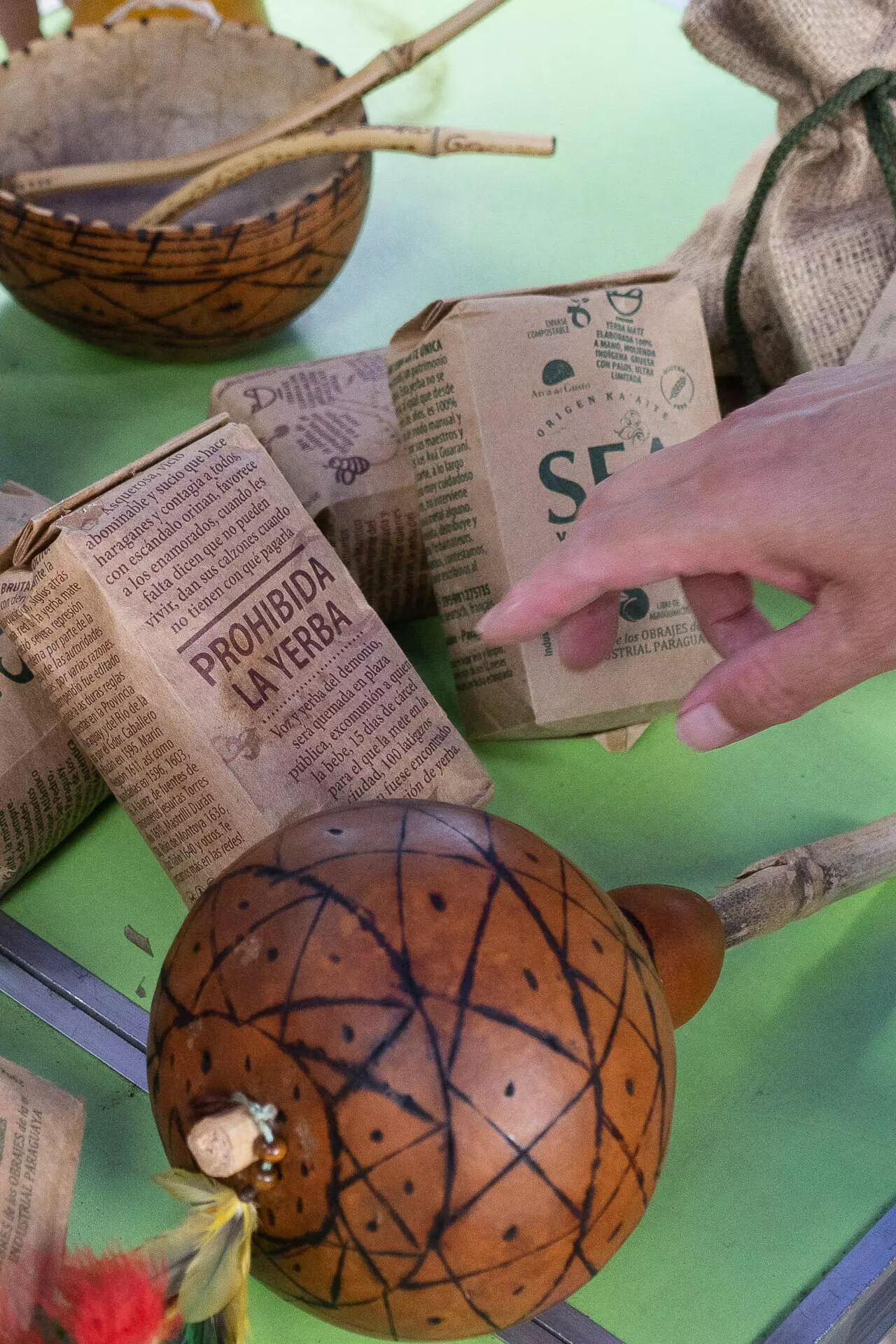

From the meeting between Ernesto and Norma, SEA was created. On the brown paper packaging is a paragraph of text, reminiscent of the times of the Inquisition: ‘YERBA PROHIBITED: Voice and herb of the devil. It will be burned in the public square, excommunication for those who drink it, 15 days in jail for those who bring it into the city, 100 lashes for those found in possession of yerba maté.’

SEA has become perhaps the best yerba mate in the world. It is the only one cataloged in The Ark of Taste, a list of 5,000 foods that humanity should preserve for its own good, according to the Slow Food Foundation, which has been promoting this global catalog since 1986.

Today Norma Ávila is the seller, promoter, producer and distributor of this yerba in Asunción and around the world, to which the product is gradually opening in one-pound (half-kilo) packets while selling at local markets selling agro-ecological products, such as the one on Saturday mornings in Plaza Italia in Asunción, my neighborhood. Norma offers the yerba and the story. She talks about where it comes from, how it is produced and who the tamoi Ernesto is. She is an excellent storyteller and customers become listeners and fans.

With her suitcase full of packets of yerba mate produced by the Avá-Guaraní people, Norma recently traveled to Berlin. There, she participates in more fairs, spreading the word about the product and the importance of maintaining the environment. She has created her own ‘mate ritual’, a ceremony that blends Guaraní history and mythology with her own songs. It is a mate tasting designed to honor the people who created it and the nature that made it possible. “Like a mini journey through the stories and the ancestral flavor, that jungle taste. That’s what I’m trying to do with the mate ceremony, to reach people’s hearts a little bit,” she says.

While their yerba travels around the world, a new spring day is beginning in Tekoha Y’apy. Victoria goes to the fields to check on the corn, cassava, peanuts, pineapple and sweet potatoes. Others take turns keeping watch over the tatuape or drying more branches. Ernesto Vera, perched on top of the giant mountain of branches and leaves, is coordinating with a large wooden pitchfork. He is in charge of knowing when the yerba is sufficiently roasted. This is a special feature of the family and communal work chain that has carried over to the modern yerba mate industry. Even in companies, these people are called urú, which in Guaraní means the head mate grower. But before all that, around four o’clock in the morning, everyone has woken up. Ernesto Vera has entered the communal house and lit a fire to heat water. It is not yet dawn when he takes the first sips of mate in this stronghold of the forest, one of the only places in Paraguay where it is still, sometimes, cold.

Santi Carneri is a journalist, photographer and documentary filmmaker. Argentinian born, he was raised in Spain and then grew up in Paraguay. He has been living in Asunción for 10 years, surrounded by about 400 pot-plants. He drinks hot mate every day, even though it’s always hot in Paraguay.

This story is part of the Colapso project by Dromómanos, an independent news producer based in Mexico.

About Dromómanos

Dromómanos is a producer of independent journalism that investigates, educates and experiments to tell the story of Latin America in collaboration with journalists from all over the region. The project began in 2011, when its founders Alejandra S. Inzunza and José Luis Pardo Veiras traveled across the continent in a third-hand Volkswagen Pointer in a bid to forge a new journalistic model of continental coverage. Together they have created more than 20 long-form reportages and Narcoamérica, a book documenting the impact of drug trafficking on everyday life in societies throughout Latin America. In the past 12 years, Dromómanos has worked with over 100 contributors and partnered with 60 national and international media outlets to address the most pressing issues for Latin Americans, such as violence, the climate crisis, authoritarianism, migration and corruption.

About the Colapso project

What happens when the power of nature intersects with human suffering? In few places can one find a more striking answer to this question about our present and future than in Latin America, the most disparate and one of the most biodiverse regions in the world. Colapso (collapse) ventures deep into the jungles, mountains, islands, forests, deserts, oceans and cities of the region, to report from the field on the symptoms and consequences of the climate crisis.

Text: Santi Carneri Tamaryn

Photos: Mayeli Villalba

Fact check: Dromómanos

Spell check (portuguese): Elvira Gago

Translation into portuguese: Paulo Migliacci

English translation: Charlotte Coombe

Visual editing and page setup: Lela Beltrão and Erica Saboya

Victoria and Ernesto grow the wild yerba mate that travels the world on the same land where they grow food for the family