“You stole it,” says Indiana Jones. “Then you stole it,” replies the Nazi, Jürgen Voller. “And then I stole it. It’s called capitalism,” says Helena Shaw, the archaeologist’s goddaughter, while smiling out the side of her mouth. Finger-picked for its selling power, this exchange is used as the trailer for the most recent film in the Hollywood saga, Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny. Assured and good-humored, Helena is justifying possession of a historical artifact that used to belong to Archimedes and that supposedly has the power to change the course of humanity. The only way to save the planet from catastrophe, according to the movie, is to keep it in a safe place – or rather, in the hands of a charming, heroic, adventurous American professor of archeology. Wait! You won’t find any spoilers here. In fact, you don’t have to wander too far into the plot to find that the recently released feature film repeats the same tired formula that has made Indiana Jones a symbol of American culture for the last forty years: the use of a colonialist and racist narrative that reinforces stereotypes by considering everything that is not a part of Western culture as exotic, dangerous, and/or a threat.

“This isn’t archeology. The idea that a white man who takes on challenges to rescue relics in inhospitable places to bring them to museums in the Global North, where they will be safe, is already a well-known but overdone plot. Indiana Jones seems to be more and more outdated,” says Bruna Rocha, a lecturer in archeology at the Federal University of Western Pará. She is referring to the imperialist premise on which museums based their actions in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, of demonstrating power through the possession of cultural materials that had great significance in their local contexts. This practice has been questioned over the years, inside and outside of academia.

In the early 1980s, when the first movie in the adventure series was released, more questions began to be asked about exploration of other peoples’ culture, tradition, and heritage for entertainment and displays of power. In the debut film, Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), Indiana Jones is immersed deep in the Peruvian forest, dodging arrows from “savage natives” to find the location of an object that, if stored in the United States, would save humanity (phew!). At this same time, in real life, a group of aborigines had released a manifesto entitled “Our Heritage is Not Your Playground,” questioning the wrongful appropriation of Indigenous cultures and offering a series of reflections on archeology and the right of Indigenous peoples to be the guardians of their own history. “Even this idea that archeologists discover where historical objects are, despite all of the obstacles imposed by the forest – something so prevalent in films – is questionable. Most of the time this happens thanks to the knowledge that local peoples have of their territories. This type of representation makes the role of local communities in building anthropological knowledge invisible,” Bruna says.

Poster for Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull: plenty of individuality-erasing mistakes

Yet the charming Dr. Jones, or better yet, his creators, continue to ignore these movements, and in the following decades they continued to offer their viewers “a sophisticated game of advertising colonialism in a breezy and fun way, which in the end seduces people and internalizes an imperialist and prejudiced discourse,” says archeologist Eduardo Neves, the director of the Archeology and Ethnology Museum at the University of São Paulo. Of course, the narrative ends up spilling over to the Amazon and its original peoples.

In 2008, with the release of the fourth film in the series, Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, the American hero returns to Peru, this time to solve an enigma hidden “in the exotic and dangerous largest rainforest in the world, surrounded by quicksand and waterfalls” (which are actually in Hawaii). Along the way, he meets Mayan warriors speaking Quechua (the language of the Inca), he is bitten by insatiable ants who devour humans (Siafu ants, only found in Africa), his travels are set to a Mexican soundtrack (in the middle of Peru), and he confronts an Indigenous tribe whose garments and makeup make them look more like zombies fresh off the set of The Walking Dead. All of this to reach Akakor, a lost city at the heart of the Amazon, surrounded by pyramids and built (shock!) by extraterrestrials.

Through deliberate mistakes like these, the producers reinforce a scheme in most of the public imagination according to which everything beyond southern borders is the same. By nullifying peoples’ individualities, histories, and cultures, at the end of the day they exclude the thing that is, or should be, the premise of archeology: showing cultural and technological diversity, bringing back the past to help build the future. “In addition, in this movie [Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull] we once again see the idea reinforced that Indigenous peoples are supposedly inferior and can’t be responsible for major architectural and cultural works. Only extraterrestrials could justify these events,” adds Adriana Schmidt Dias, a professor with the History Department at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS). It all gets worse when the series’ creators occasionally try to soften the perception that they are stigmatizing peoples and minorities. It is not unusual for a representative from this contingent, someone darker skinned, with peculiar mannerisms, heavy makeup and an exotic accent, to join the team of good guys. It’s the famous exception that proves the rule. Or rather, instead of softening it, it makes it starker. “These communities continue to be unfortunately depicted, viewed as having irrational beliefs and ceremonies, while the figure of the white man from the North represents rationality. Reiterating this view in the present day is sad and arrogant,” says archeology professor Bruna Rocha.

It’s not hard to understand why a movie like this continues to pack cinemas in the USA and Europe, the heart of this hegemonic ideology. But what justifies having a legion of fans in countries like Brazil? The answer is simple, says Eduardo Neves: “It’s an ideology that we unconsciously reproduce and internalize in the countries of the South, as the result of our own process of colonization. The fact that it is such a long-running series of films and that it was even successful here shows how the world is still divided, and how racism and the colonialist vision have even taken root in the countries of the Global South.”

In the saga’s last film, where an already elderly (yet still charming) Indiana Jones returns for a final adventure, repeating patterns and reinforcing stereotypes from inside the screen, here on the outside, a plot twist typical of our contemporary age has finally put his character in check. In late June, the same week when the movie – whose character is known for saying “That belongs in a museum!” – premiered in cinemas the world over, Denmark announced that it was returning a Tupinambá cape to Brazil, stolen from the country three centuries ago and kept until today in a Copenhagen museum. “We believe it is an ancestor. This isn’t about a work of art, a mere object,” said a Tupinambá leader when the announcement was made.

At the end of all this, Dr. Jones is apparently retired. Only time will tell if this spells the end for an outdated view of the world. What we do know is that, for now, the peoples of the forest will continue, in practice, to confront the many, many real-life Indiana Joneses, some in suits and ties, others driving tractors and tearing holes in the land, and others in the stories that are ultimately the past, present, and future of all of us.

Spell check (Portuguese): Elvira Gago

Translation into Spanish: Julieta Sueldo Boedo

English translation: Sarah J. Johnson

Photography editing: Marcelo Aguilar, Mariana Greif and Pablo Albarenga

Page setup: Érica Saboya

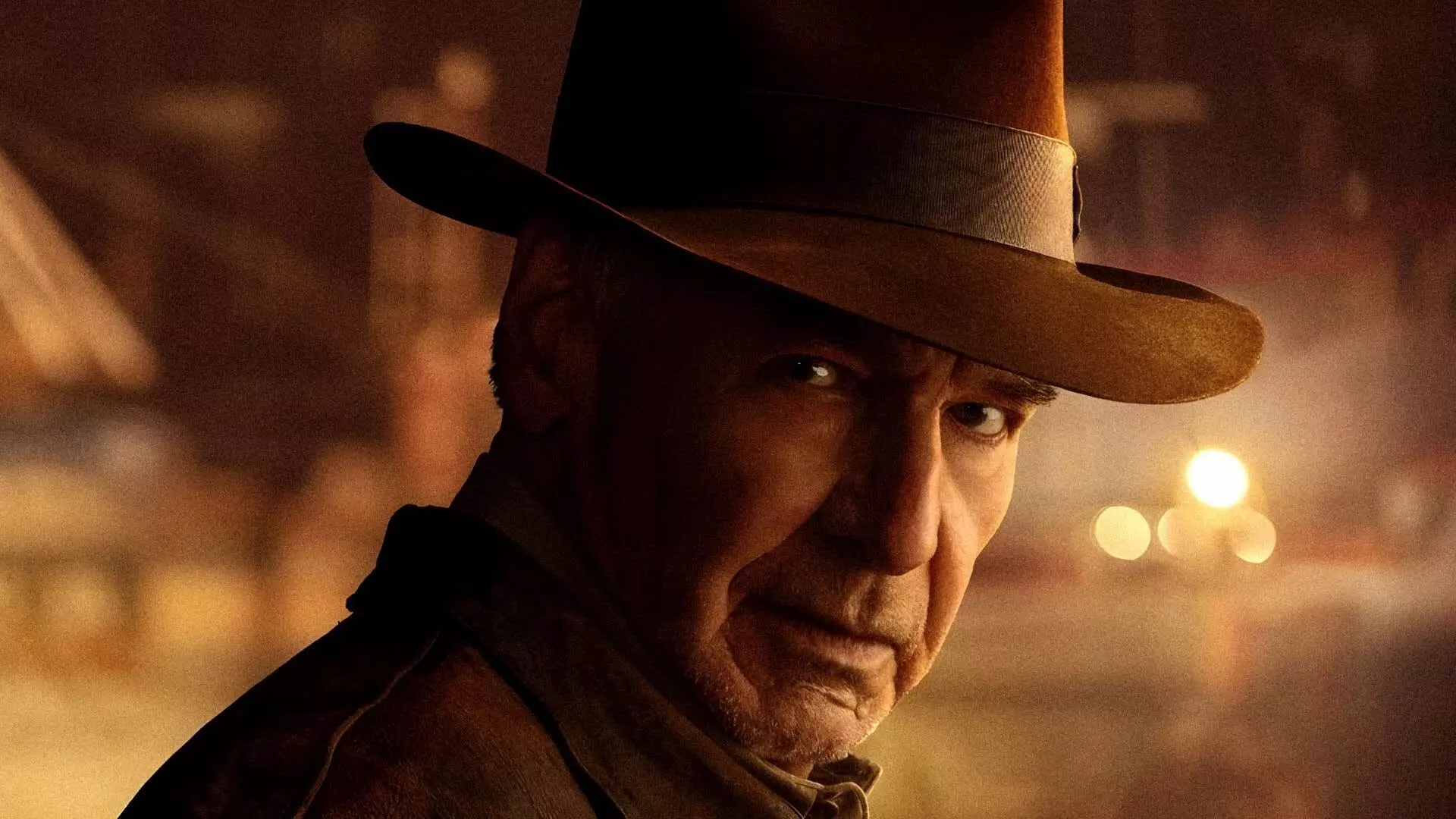

Between one adventure and another, the new old Indian Jones reinforces Imperialist and prejudiced discourses. Photo: Reproduction/Disney