In under two years, the cattle ranches that supply Brazil’s three largest meatpackers—JBS, Marfrig, and Minerva—have deforested the Cerrado biome in Mato Grosso state equivalent to more than the area of Chicago, according to a new report by the British NGO Global Witness, analyzed in Brazil exclusively by SUMAÚMA. The study points out that most of this destruction occurred illegally.

In 2023, for the first time since 2018, the Cerrado savanna forest outpaced the Amazon as the most heavily deforested biome in the country. Half of the Cerrado’s forest cover has already been razed to clear the way for pastureland, cropland (especially for soy, corn, and cotton), and cities.

Located in the Central-West region of Brazil, the state of Mato Grosso has the country’s largest cattle herd. Data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics show the state had 34 million cattle in 2022, or nine head for every human inhabitant. It was also the state that killed the most beef cattle in 2022: some 4.7 million, or 16% of the nearly 30 million head slaughtered across Brazil. The total number of Brazilian beef cattle butchered in 2022 climbed 7.5% over the previous year.

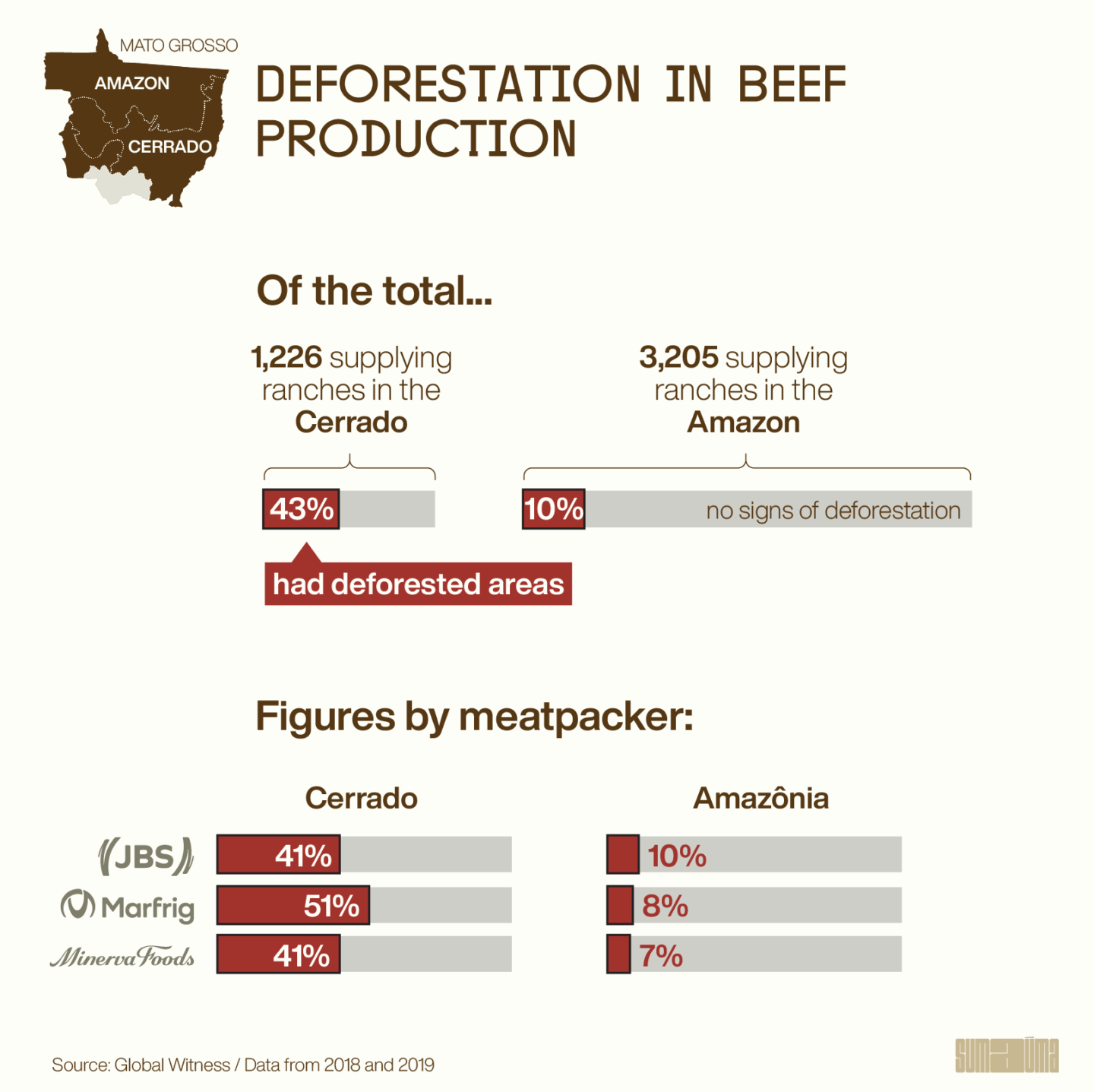

Mato Grosso has a unique combination of biomes, with the northern region home to the Amazon while the more central and southern regions, of equivalent size, lie in the Cerrado. This allowed Global Witness to use state data to compare the impact of cattle ranching in both biomes. The result is chilling: the suppliers of JBS, Marfrig, and Minerva were tied to five times more deforestation in the Cerrado than in the Amazon portion of the state in 2018 and 2019, the period analyzed by the NGO. Each head of cattle purchased in Mato Grosso by the three big meat firms was potentially linked to an average of 0.28 acres of deforestation in the Cerrado. In the Amazon portion of the state, the deforestation footprint averaged 0.021 acres per animal raised for sale and slaughter.

According to Global Witness, farms that supply animals to JBS, Minerva and Marfrig deforested 147,991 acres (59,890 hectares) of forests in the Amazon and Cerrado portions of Mato Grosso between 2018 and 2019. Most of them – 146,582 acres (59,320 hectares) – were felled without authorization,

Global Witness found the cattle ranches that supply animals to the big three have already deforested 231 square miles in the Amazon and Cerrado regions of Mato Grosso, 229 square miles of which were cleared without authorization. The meatpackers disagree with the methodology used in the study (read more below).

“The Amazon has legal protections that the Cerrado does not. Therefore, we believe that some of the cattle ranching that would be happening in the Amazon is moving across to the Cerrado […]. Essentially, they are displacing the problem,” said Veronica Oakeshott, Forests Campaign Lead at Global Witness, in an interview with SUMAÚMA. As the leader of the organization’s campaign to protect the forests that can ease the climate catastrophe, Veronica works to expose the companies and financial institutions behind this destruction and push for legislative changes that will save the biodiversity that is left.

Mato Grosso exemplifies how environmental legislation is more tolerant of deforestation in the Cerrado. The state requires rural properties to preserve only 35% of the original vegetation in this biome, while the percentage can reach 80% in the Amazon portion. Global Witness also underscores that one in three animals purchased by JBS, Marfrig, and Minerva from ranches located in the Mato Grosso Cerrado grazed in areas that were deforested with the express purpose of opening space for livestock. Much of this meat was sold abroad. In 2020, Brazil as a whole exported almost twice as much beef raised on pastures in the Cerrado as in the Amazon. China usually far outranks other buyers of beef slaughtered in the state, with Egypt and the United States coming in second and third. In 2022 alone, exports generated the equivalent of $2.6 billion.

Growing consumption of meat by humans is one of the culprits behind forest destruction and global heating. Photo: Paulo Whitaker/Reuters

The human appetite for beef has been a decisive factor in the devastation of Brazilian forests. “Two-thirds of cleared land in the Amazon and Cerrado biomes have been converted to cattle pasture, making the Brazilian cattle sector responsible for one-fifth of all emissions from commodity-driven deforestation across the entire tropics,” states a 2020 study published in PNAS, the official journal of the US National Academy of Science. Global Witness points out, “it is no coincidence that Mato Grosso also has Brazil’s second highest level of tree cover loss according to the most recent Global Forest Watch data.” Leading the list is the state of Pará, another major producer of slaughter cattle.

The destruction promoted by the suppliers of JBS, Marfrig, and Minerva and now revealed by Global Witness is financed by the biggest banks and investment funds in Brazil and the world. Bradesco BBI, Santander, BTG Pactual, XP Investimentos, Itaú BBA, HSBC, Barclays (the British bank known for years for sponsoring England’s Premier League), and Merrill Lynch together have underwritten billions of dollars in bonds, allowing the Brazilian big three to borrow money on the financial market to boost their operations in the country.

High-profile investment funds such as BlackRock and Capital Group are shareholders in this trio of meatpackers.

Oakeshott says meat processing companies hold major responsibility for deforestation, and so do their bankers and financiers: “The profits from the destruction of this precious Brazilian asset are going to places around the world, and we feel that those people need to take responsibility.”

In their replies to SUMAÚMA and Global Witness, meatpackers, banks, and investment funds declared their commitment to environmental sustainability. Marfrig, JBS, and Capital Group also questioned the British NGO’s research findings. BlackRock said that in 2023 it “voted against or abstained from supporting a number of management proposals at JBS, Marfrig, and Minerva over corporate governance-related concerns.” Read a summary of the statements from Minerva, Marfrig, JBS, Santander, HSBC, Barclays, BlackRock, and Capital Group at the end of this report.

The black box of Animal Transport Permits

Global Witness arrived at its findings by cross-referencing publicly available data with information the authorities have intermittently tried to keep confidential. This is the case with Animal Transport Permits, a document required to transport animals within Brazil. In theory, the document should indicate the origin of the livestock and its travel route. However, since the information is self-reported, fraud is common. For example, a permit might claim the animals were raised on a legal ranch where no land was illicitly cleared, when in fact the cattle grazed almost all their lives in prohibited areas such as Indigenous territories or conservation units, before being hauled away to their deaths.

“The Animal Transport Permit is the official document for transporting animals in Brazil and contains essential information on traceability (origin, destination, purpose, species, vaccinations, among others),” as stated on the federal government website. The document must be filled out by a veterinarian and, along with other data, indicates who sold and who purchased the animals—and where they were raised.

Global Witness obtained Animal Transport Permits issued in Mato Grosso from January 2018 to July 2019 from a state website. For information on the ranches that sold their animals for slaughter to the three beef giants—JBS, Marfrig, and Minerva—it relied on CAR, a public database where rural landowners register such data as the precise geographic location of their property.

The location of each cattle ranch was then cross-referenced with information from the Brazilian space research agency’s Terra Brasilis geographic data platform, which provides statistics on forest loss. Finally, Global Witness searched Deforestation Permits in Mato Grosso, a license required for the legal deforestation of any area, public or private, in any biome. By cross-referencing all these data, the study found that 9.7% of the cattle ranches in the Amazon and 42.8% in the Cerrado had erased areas of forest in 2018 and 2019. And in both biomes, 99% of this deforestation was done without any link to authorization documents issued by the state government, the NGO says.

Global Witness limited its survey to this 18-month period in 2018 and 2019 for a simple reason: this was when the public had access to Animal Transport Permits issued in Mato Grosso. Since then, these documents have been removed from public access by various state administrations—and also by the federal government. This has hampered nongovernmental oversight of deforestation by the Brazilian beef sector.

The argument for this secrecy is made explicit in a number of documents, such as a technical note issued by the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, and Supply, dated April 2019—early in the administration of far-right president Jair Bolsonaro: “This Ministry considers that, at an individual level, both registry data as well as [Animal Transport Permits] contain information of a personal nature, so they are not of collective or general interest. This information is eminently pertinent to the activity of the Animal Health Defense agency, which affords traceability of herds and oversight of transport, and is fundamental in the decision-making process regarding public policies in agricultural defense but is not intended for the general public. Possible impacts on the agricultural market must also be taken into account,” reads the document, signed by Bruno de Oliveira Cotta, a veterinarian who is a career civil servant and continues to coordinate the ministry’s Animal Transport and Quarantine area.

Bolsonaro hasn’t been president since January 2023, but Cotta remains in the same post. Nor has the Agriculture Ministry changed its stance. The ministry is currently headed by Carlos Fávaro, at the invitation of President Inácio Luiz Lula da Silva. Fávaro is a large soybean farmer who belongs to the Social Democratic Party and is a senator for Mato Grosso. When approached by SUMAÚMA, the ministry replied through its press office that it “maintains the position that the [Animal Transport Permit] is not a public document, as it contains information of a personal nature. However, the matter is being evaluated from a legal standpoint, so at the moment it is not possible to define whether the document can be made public.”

Carlos Fávaro, senator for Mato Grosso and a large soybean farmer, is President Lula’s Minister of Agriculture and Livestock. Photo: Mateus Bonomi/Agif/AFP

The Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office has filed various suits questioning the need for confidentiality of the permits. “It is our position that [Animal Transport Permits] are public data. There is no reason to keep these documents confidential,” federal prosecutor Daniel Azeredo told SUMAÚMA. Azeredo is the author of the Term of Adjustment of Conduct (TAC), under which, since 2009, slaughterhouses operating in the state of Pará must audit information on the origin of the animals they butcher.

The Term of Adjustment of Conduct years later gave rise to the Beef on Track protocol, now coordinated in partnership with the Brazilian NGO Imaflora, which offers such services as forest certification and due diligence. The Brazilian Beef Exporters Association (Abiec) only formally joined the protocol in mid-2023, although some of its members—such as JBS, Marfrig, and Minerva—had already adopted it.

The Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office has filed public interest civil lawsuits with Federal courts in 12 Brazilian states, asking them to make Animal Transport Permit data public. In Mato Grosso, the office has since 2019 recommended that the state sanitary agency Indea disclose the information contained in the Animal Transport Permits issued by the state, including the identification of cattle buyers and sellers. The recommendation has been ignored since then, leading the prosecutor’s office to file another public interest civil lawsuit with the courts, in November 2023. Like the other suits brought by the public prosecutors, no ruling has been handed down on the case in Mato Grosso.

SUMAÚMA asked the Mato Grosso sanitary agency about the lack of transparency with the permits. Through its press office, one of the agency’s coordinators, João Néspoli, replied that the permits are published but with certain information omitted, such as name, business entity tax ID, and location of buyers and sellers—which in practice renders the data useless to anyone who wants to trace the links between cattle ranching and deforestation, as Global Witness was able to do with the 2018-19 data. The state sanitary agency uses Brazil’s General Personal Data Protection Law to justify these omissions.

Prosecutor Azeredo, however, doesn’t believe that transparent permits alone would do away with these connections between the meat industry and deforestation. Permits only state which cattle ranch was the final, or direct, supplier to a meatpacking plant. “But this ranch normally buys cattle from several others to resell to the meatpacker. They’re what we call indirect suppliers,” he explains. This is why the prosecutor advocates a system in Brazil where each animal is tracked from birth by satellite, thanks to an ear tag chip.

“We’ve been advocating this for several years, as a measure needed to combat deforestation,” says Azeredo. But since no legislation mandates adoption of the system, the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office has its hands tied—it can’t ask the courts to enforce a nonexistent law. “This depends on a decision by the government, by the Ministry of Agriculture, but also on state governments, companies themselves, supermarkets. Many people could lead this process,” Azeredo explains. SUMAÚMA also asked the Agriculture Ministry if there is any study or project underway that would require real-time satellite tracking of beef cattle, including the mandatory attachment of ear tags with electronic chips. The ministry did not respond.

Asked about Global Witness’s findings in Mato Grosso, the Agriculture Ministry replied, “It is not possible to issue an official position on the survey, since the ministry has not had access to the document in full.” The department also said that “control and oversight of deforested areas, regardless of the economic activity carried out there, falls to Ibama [Brazil’s environmental protection agency].”

When asked to comment on the ministry’s response, Ibama said the agency “has been working to monitor the production chain associated with illegal deforestation, such as cattle ranching, […] and has conducted operations […] to monitor the meatpackers that buy cattle from embargoed areas.” The note adds that “most illegal deforestation in the state of Mato Grosso falls under the primary jurisdiction of the state government in terms of oversight and control. However, Ibama also plays an active role in this process.”

The Mato Grosso State Department of the Environment said that it will “comment after learning the full content of the study by Global Witness.” However, the department also said it has “acted firmly and with zero tolerance in the fight against illegal deforestation and environmental crimes, through Operation Amazon in the field, satellite-image oversight, levying of fines, and the embargo and seizure of offenders’ equipment.”

Veronica Oakeshott, of Global Witness, however, doesn’t see the lack of tracking chips as the only roadblock to transparency. She calls on meatpackers to ensure that Animal Transport Permits are truly transparent. “China […] is increasingly interested in these issues. At the moment, they don’t have the requirements that for example the European Union [will introduce in December 2024]. In the long term, I suspect that will change, as China moves and perhaps redefines its […] requirements.”

Cerrado, the forgotten biome

The data surveyed by Global Witness in Mato Grosso are symptoms of a larger problem: the Cerrado is the biome that has suffered the greatest destruction with the advance of agribusiness in Brazil. In addition to cattle, large-scale monocultures such as soy, corn, and cotton have produced successive deforestation records. In November 2023, the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change announced that the Brazilian Cerrado lost a remarkable 4,250 square miles of vegetation from August 2022 to July 2023—an area more than twice the size of the state of Delaware or over half the size of Wales.

Every 0.28 acres deforested for the grazing of a single animal may be the natural habitat for nearly 100 lizards. Photo: Amanda Perobelli/Reuters

This may not seem like much, compared to the more than 772,000 square miles covered by the Cerrado—about 25% of Brazil’s territory—across the states of Goiás, Mato Grosso, Mato Grosso do Sul, Tocantins, Minas Gerais, Bahia, Maranhão, Piauí, Rondônia, Paraná, and São Paulo, plus the Federal District. But more than half of this area has already been deforested, the result of a process that began in the 1970s when the state-owned agricultural research body Embrapa introduced the use of limestone to improve the fertility of soil considered “poor.” This new practice triggered a land rush in the Cerrado. Yet this biome is crucial to the water security of a considerable part of South America. Eight of Brazil’s 12 hydrographic regions—including the Araguaia, São Francisco, and Paraná rivers—have their sources in the Cerrado, which is called the “cradle of waters.”

A scientific study in 2022 and presented at the UN Conference on Climate Change, COP27, held in Egypt, found that flow for Cerrado rivers dropped 15.4% from 1985 to 2022. This can be blamed on the forest loss caused by agribusiness and on climate change. And it will get worse: by 2050, flow for these rivers is forecast to fall one-third (34%), unless this destruction is reversed, according to the same study, led by the geographer Yuri Salmona, who holds a doctorate in forest sciences from the University of Brasilia.

The Cerrado landscape is characterized by trees with twisted trunks and branches and by majestic plateaus such as Chapada Diamantina, in Bahia, or Chapada dos Veadeiros, in Goiás. It is home to more than 2,500 species of vertebrates, such as the maned wolf, as well as more than 11,000 species of plants. The landscape is quickly giving way to the monotony of large estates that produce monocultures such as soy—in some states, with the crop planted right up to the edge of the highway—or pastureland, both of which wipe out local biodiversity.

The Cerrado is the second largest biome in South America and is vital for eight of Brazil’s 12 hydrographic regions. Photo: Marizilda Cruppe/Greenpeace

The 0.28 acres of deforestation allegedly linked to each head of cattle purchased by JBS, Marfrig, and Minerva in the Mato Grosso Cerrado may be the habitat, for example, of nearly 100 lizards and thousands of termites—insects that play a fundamental role in maintaining wildlife in the biome, according to calculations by Reuber Albuquerque Brandão, professor with the Forest Engineering Department at the University of Brasilia and coordinator of the institution’s Fauna and Conservation Units Laboratory.

“One of the main characteristics of the Cerrado is the high diversity of species from one place to another. An area of one thousand square meters [10,700 square feet], which is the average area of forest cut down to accommodate each head of cattle in the Cerrado, according to Global Witness, can be the habitat for 80 lizards representing up to ten species, for example, and hold four to five large termite mounds. It’s simply impossible to count how many termites live in each, but one mound can move about four metric tons of soil a year, while it also serves as a shelter for snakes, rodents, lizards, amphibians, and hundreds of opportunistic invertebrates,” he says. Brandão’s doctoral research investigated the way of life of lizards on the islands formed by the Serra da Mesa Hydroelectric Power Plant, which has been damming up the Tocantins River in Minaçu, northern Goiás, since 1998.

“If these thousand square meters are floodplain, it’s possible to find up to 20 species of amphibians there,” continues Prof. Brandão. “Removing the flora from a thousand square meters of a seasonably flooded area—quite common when opening up pastureland in the Cerrado—means destroying the breeding habitat for some 20 species of amphibians, which can easily reach 200 individuals during breeding periods.”

In a thousand square meters of the Mato Grosso Cerrado, it is also possible to find 150 trees of at least 25 species, calculates forest engineer Renata Françoso, a professor at the Federal University of Lavras, in Minas Gerais. All of this life—lizards, amphibians, termite mounds, trees, along with fungi, grasses, and other animal species—is being annihilated to open space for one single steer so that mega meatpackers can reap profits, according to the Global Witness survey.

Article 225 of the Brazilian Constitution, which opens the chapter on the environment, stipulates that “everyone has the right to an ecologically balanced environment, which is a people’s common asset and essential to a healthy quality of life, making it imperative for the Government and the collectivity to defend and preserve it for present and future generations.” Paragraph four of the article specifies that “the Amazon Forest, Atlantic Forest, Serra do Mar, Mato Grosso Pantanal, and Coastal Zone constitute national heritage.” The constitution doesn’t contain a single mention of the Cerrado—already coveted by agribusiness back then.’

A plan to curb deforestation

The lack of attention from government authorities explains why the Cerrado is being cleared of forest five times faster than the Amazon. In 2019, Jair Bolsonaro issued a decree abolishing the Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Deforestation and Burn-offs in the Cerrado, or Cerrado Plan, established in 2010. In late November 2023, the plan was relaunched by the Minister of the Environment and Climate Change, Marina Silva.

“Nature is not assimilating what we have legislated for the Cerrado so far,” Marina said last September during the ceremony to launch a public consultation on the Cerrado Plan. When the plan was reintroduced in November, her ministry reported that agricultural expansion and land speculation were among the main causes of destruction of the biome, which has little protection under law: clearance of more than half of the 4,250 square miles deforested from August 2022 to July 2023 was authorized by state governments or occurred within parameters accepted under Brazil’s Forestry Code.

As the new phase of the Cerrado Plan is implemented, the ministry led by Marina aims to repeat the success of the Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Deforestation in the Legal Amazon, which successfully reduced deforestation in the Legal Amazon by 83% from its inauguration in 2004 through 2012. It remains to be seen whether there is still time to accomplish as much.

How much meat is sustainable?

What Global Witness discovered about the three giant meat processors’ supply chain in Mato Grosso raises a question: Can the world keep on eating so much meat? In 2016, agriculture accounted for 33% of Brazilian greenhouse gas emissions, the culprit behind global heating, according to Brazil’s Fourth National Communication to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), a document produced in 2020—that is, under the Bolsonaro administration. And no less than 19% of Brazil’s greenhouse gas emissions come from the methane that cattle and other ruminants produce during digestion.

Brazil currently has one of the largest cattle herds in the world. In 2022, it had more than 234 million head—more than the number of human beings in the country. “Demand is growing daily. In the last 50 years, meat production has more than tripled. The world now produces more than 340 million metric tons a year,” boasts the website of the Mato Grosso Meat Institute, an agency tied to the state government and assigned the “mission of promoting Mato Grosso beef.”

It costs the Brazilian environment dearly. The most recent data from the Climate Observatory, released in late November 2023, show that agricultural and livestock-raising activities combined increased their carbon emissions by 3% in 2022, compared to 2021. It was the second consecutive year with a rise of more than 3%, something that hadn’t happened since 2004, and it is explained by the growth in Brazil’s cattle herd. “Even with the drop-off in fertilizer consumption, which reduced emissions by agriculture, the increased emissions by livestock farming pushed the figure for the whole sector up,” says Gabriel Quintana, with the Brazilian NGO Imaflora. Agriculture and livestock were responsible for 27% of all gross Brazilian emissions in 2022. The figure is as high as 75% of all Brazilian emissions if associated forest clearance is included.

But there is a final link in the chain: the consumer, who needs to remember that the steak or hamburger they put on their plate might have caused deforestation. In 2022, meatpackers put the equivalent of 62 pounds of beef per inhabitant on the Brazilian market–a figure that had reached almost 95 pounds a year in 2006. Brazil is one of the largest consumers of beef, but among the countries it trails are the United States (81.5 pounds per inhabitant on the market in 2020) and Argentina (almost 104 pounds per inhabitant, also in 2020), where barbecue is part of the local culture. In the United Kingdom, where Global Witness is based, average beef consumption per inhabitant was almost 40 pounds in 2020.

“I think people are always going to want to have beef. We don’t want to prevent anyone from having beef,” says Veronica Oakeshott, of Global Witness. “But it is completely unsustainable for the entire world to eat as much beef as people in the UK and in the US do. We all need to think about eating less beef, and that ultimately will be a personal choice for people. But it’s ecologically very unsustainable to have a meat-heavy diet.”

Agriculture and livestock accounted for 33% of Brazil’s greenhouse gas emissions, which cause global heating. Photo: Rubens Cavallari/Folhapress

What those involved say

When asked by SUMAÚMA about the findings of the Global Witness study, JBS replied that “the [British organization’s] analysis disregards the terms of the Beef on Track protocol, which is followed by the entire livestock sector.” Consequently, JBS says, Global Witness reaches “misleading conclusions by classifying as ‘non-compliant’ any property exceeding 6.27 hectares without plant cover, not necessarily continuous.” Finally, it claims that “all purchases” on which the report is based were regular and met “the socio-environmental criteria of the time of the transaction.” In a reply sent to Global Witness, JBS said that “it has identified the CARs (Rural Environmental Registry) of only 482 out of the 611 farms highlighted by Global Witness in its supplier database.”

Marfrig told SUMAÚMA in a statement that Global Witness had provided it with “only CAR [Rural Environmental Registry] documents for property that had some type of environmental liability, especially deforestation.” By analyzing these “in the light of PRODES [Amazon Deforestation Monitoring Project], a legal, official instrument for verifying deforestation in the region, Marfrig demonstrates and corroborates the fulfillment of 100% of the criteria of its zero-deforestation purchasing policy and is fully compliant with its other commitments”. According to the company, nine ranches reported by Global Witness “are not registered in Marfrig’s databases.” Of the remainder, 214 did not overlap with records in the PRODES monitoring project, seven recorded deforestation on polygons smaller than 6.25 hectares (permitted under Beef on Track), and 16 were subsequently blocked. Therefore, according to Marfrig, “the allegations [by Global Witness] are unfounded.” The company also says “that it does not purchase animals from deforested areas, conservation units, Indigenous Territories, Quilombola Territories, embargoed areas, or property on the dirty list of labor analogous to slavery,” in addition to complying with Beef on Track.

Global Witness explains that its methodology considers that deforestation took place on any ranch where satellites identified polygons without plant cover whose combined areas surpass 6.27 hectares. Beef on Track only considers deforestation to have occurred when each analyzed polygon has an individual area exceeding 6.25 hectares. The latter approach derives from PRODES deforestation monitoring methodology; although the system can identify the removal of vegetation in areas as small as one hectare, PRODES only considers that deforestation has taken place when it involves a continuous area exceeding 6.25 hectares. In other words, for example, a ranch with two deforestation polygons, each four hectares in size but in different locations, will not be considered a deforester under Beef on Track, even though a total of eight hectares has been destroyed.

The British NGO believes this parameter fails to accurately capture all deforestation in the livestock supply chain.

“Global Witness accepts that we used a slightly more stringent process in our methodology for identifying small cases of deforestation within cattle farms than that of the public prosecutor, but believes the difference this made to our overall findings is minimal. This is the only small difference in our approach to that of the public prosecutor, and we believe it makes our work more robust.”

“The evidence which Global Witness has identified is one of a failure of diligence around supply chains. Global Witness does not suggest that JBS, Marfrig or Minerva have authorised or commissioned the deforestation of any land from any of the farms or ranches that supply animals to them. However, the companies are in a position to influence change of practice on the ground, and to curb illegal deforestation,” the NGO says.

Minerva Foods neither questioned nor addressed the findings of the Global Witness report in its responses to SUMAÚMA and the NGO. Instead, it lists what it considers actions in line with its “Commitment to Sustainability.” Minerva says it “spearheaded the utilization of geospatial monitoring in monitoring 100% of its direct suppliers across all the biomes it operates in Brazil (Amazon, Cerrado, Pantanal, Caatinga, and Atlantic Forest) in 2020.” “This means that Minerva Foods’ production chain is free of illegal deforestation, labor practices similar to slavery or child labor, overlaps with protected areas, or environmental embargoes” and that the external audits conducted have indicated that “100% compliance was achieved for transactions conducted from January through December 2021” in Mato Grosso. The data in the Global Witness study, it should be remembered, are from 2018 and 2019.

Itaú bank, which endorsed bonds issued in 2017 by Minerva Foods, told SUMAÚMA in a note that it “understands that traceability in the meat chain affords a series of benefits not only to the environmental issue, with regard to deforestation, but also to the social issue and food security.” The text of the note says “the bank does not comment on specific clients [but] underscores that it is committed to the development of a stronger, more sustainable meat chain,” including environmental and social risk assessments for granting credit to rural producers and adherence to the protocol of the Brazilian Federation of Banks, Febraban, whose standards seek to end illegal deforestation in the Amazon, including in the meat production chain, by 2025.

Santander, which endorsed bonds issued by Marfrig in 2019, sent a note to SUMAÚMA in which it “clarifies that its financing of agribusiness, including meatpackers, is conducted in compliance with applicable regulations and based on best socio-environmental practices.” “Issuances of debt securities, in particular, are also subject to local and international capital market rules and investor scrutiny,” the text continues. Lastly, Santander says that it is a “member of the forestry and agrobusiness committee of [the Brazilian Federation of Banks] Febraban, which in March 2023 approved a protocol that established standards for managing the risk of illegal deforestation in the beef chain […] and requires clients who process beef with slaughterhouses in the region of Brazil’s Legal Amazon to end illegal deforestation by December 2025.”

Bradesco, a bank that endorsed bonds issued by Marfrig and Minerva Foods between 2017 and 2019, was asked by SUMAÚMA to comment on deforestation in the production chain of these two meatpackers. It replied that it had no comment. BTG Pactual, underwriter of Marfrig bonds, was contacted through its press office, coordinated by one of Brazil’s largest public relations agencies, FSB. The questions were received but never answered. The bank XP, another underwriter of Marfrig bonds, was also contacted via the agency Fato Relevante, which advises it, but it never replied to the questions SUMAÚMA posed via email and telephone.

HSBC, which has endorsed Marfrig and Minerva bonds, begins its reply to Global Witness by stating that it “understand[s] the environmental concerns around industrial livestock companies” and “does not wish to finance unacceptable impacts in this potentially high-risk sector.” Despite this, the bank continues, “our duty of client confidentiality prevents discussion of specific cases or companies.” […] “HSBC’s name appears on company share registers for a number of reasons, including where we act as nominee or custodian for our customers.” HSBC also stated that the bank “engage[s] with companies, sometimes in collaboration with other investors, raising concerns including deforestation risk.”

The British bank Barclays, which underwrites JBS bonds, told Global Witness it would not comment on the report for reasons of client confidentiality. However, it said that it has “strict requirements in place which apply to any companies directly engaged in […] the production or primary processing of beef in high deforestation risk countries in South America,” which “include prohibiting the provision of financial services for companies that produce or process beef from deforested areas of the Amazon, and requiring that these companies have commitments in place to achieve fully traceable and deforestation-free South American beef supply chains by the end of 2025.”

BlackRock stated that it is “a minority shareholder in JBS, Marfrig, and Minerva on behalf of clients” of the fund. “When we consider companies to have made insufficient progress on issues material to long-term financial value creation, we express our concerns in our voting for those clients who have authorized us to vote on their behalf. In 2023, BIS voted against or abstained from supporting a number of management proposals at JBS, Marfrig and Minerva over corporate governance-related concerns,” the investment company added.

Capital Group told Global Witness that it “regularly engages with management teams of companies we invest in, including recently with JBS, on a variety of issues.” It added that the report produced by the British organization includes “numbers […] at odds with disclosures from the company,” and therefore suggested contacting JBS directly.

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Spanish translation: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Diane Whitty

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Layout and finishing: Érica Saboya

Editors: Viviane Zandonadi (editorial workflow and copy editing), and Talita Bedinelli (coordination)

Director: Eliane Brum

With half of the biome’s forest cover already destroyed, the diversity of the Cerrado has given way to a monotonous landscape. Photo: Cesar Diniz