Bepdjo Mekrãgnotire was collecting brazil nuts near his village in the Baú Indigenous territory last year, when distant explosions shattered the still of the forest.

That was how he found out that, a few miles from his territory in the Amazon rainforest, British mining company Serabi Gold was breaking open 4.5 metre-wide tunnels for underground gold extraction.

“The noise startled us,” Mekrãgnotire, a member of the Kayapó people who works with NGO Kabu Institute, said. “The company should have consulted us first. We have the right to be heard.”

Serabi is also mining without authorisation from Incra, the government agency that owns the land, an investigation by Unearthed and partners has revealed. A high court ruled in 2021 no more should be given until Indigenous consultation is complete, but last year two government agencies renewed them anyway.

In a vulnerable region defined by tension between resource extraction and forest conservation, a tangle of contradictory rulings from different government agencies has raised questions over whether the mine should be suspended.

Serabi told Unearthed it is “completely comfortable with our legal position”, complies with the Brazilian legal mining framework and has all the necessary permits for Coringa. Others disagree.

“Everything regarding this project is wrong,” said Ana Carolina Alfinito, a legal consultant at Amazon Watch, a nonprofit organisation working to protect the rainforest and Indigenous people.

.

Disputed land

Serabi Gold – which is listed on both the AIM London and Toronto Stock Exchanges – acquired the Canadian company Chapleau, which held the Coringa mining project, in 2017. In 2022 the British firm started to truck ore for processing at a sister mine 124 miles north.

But Coringa is sited inside a sustainable land reform settlement – a swathe of Amazon forest managed by government land agency, Incra. And Incra says it has never authorised mining or research activities in the settlement.

“It is a region of great tension due to land grabbing, marked by deforestation and violence against small farmers and traditional peoples,” said Alfinito.

These settlements are designed to alleviate rural poverty while helping to protect the Amazon from the advance of agribusiness. But this part of Pará is known for violence linked to land and environmental disputes.

The Terra Nossa settlement is no different: the area has been targeted by land grabbers, some of whom have transformed swathes of the settlement into soy plantations. At least five people have been murdered there since 2011.

Created in 2006, Terra Nossa PDS was intended to provide smallholdings for 1,000 families, but only 300 have been relocated to the 1500 sq km (580 sq mile) settlement, due to the refusal of multiple land grabbers to leave the area.

Incra says that in fact, it is alleged land grabbers who negotiated the company’s presence in the area: official documents show that Chapleau, a Canadian company now fully owned by Serabi, signed contracts with an individual named Benedito Gonçalves Neto, who Incra concludes had taken over 68 sq km of the settlement “fraudulently”.

ILLEGAL MINING AREAS THAT STRETCH FOR MANY KILOMETERS IN LONG VALLEYS NEAR THE BAÚ INDIGENOUS LAND. PHOTO: HELENA PALMQUIST/ PUBLIC PROSECUTOR’S OFFICE FOR THE STATE OF PARÁ

According to Antônio José Ferreira da Silva, an Incra official who wrote a 2017 report about the unauthorised mining, Neto was one of 80 individuals identified as having fraudulently taken over large chunks of land.

“Benedito simply appropriated the land and said that it was his,” da Silva told Unearthed. “So much so, that we have an [ongoing] administrative process at Incra to take back these areas.”

According to Incra’s report, Chapleau signed agreements with Neto and his family in 2007, 2013 and 2016, allowing Chapleau to explore and mine in three farms claimed by Neto’s family.

But Incra concludes that these contracts were “based on precarious documentation” provided by people who are not recognized by Incra as “legitimate occupants of the project”.

The last deal, from July 2016, established that Chapleau would pay the “land owners” a single payment of R$21,428 (£3,420), monthly payments of R$1,428 (£228) and royalties from the ore extracted. In exchange, the company could do whatever it wanted in the area, including ore research and mining, deforestation, water collection, construction of tailings ponds, buildings and a processing plant.

“From the signing of the contracts Chapleau effectively controlled the areas, acting as an enclave in the settlement project,” stated Incra in the 2017 report.

Brazil’s mining code allows companies to sign agreements with whoever is the “possessor” of the land during the trial mining period and pay royalties, regardless of whether their claim is legally recognised. Unearthed understands that Chapleau paid the fees to Neto and his associates but that Serabi suspended those payments when it took over the mine.

But the current situation at Coringa appears to be that the British company is extracting gold ore from the Amazon without approval from the land agency, without a completed consultation of nearby indigenous groups, and without the payment of a fee to either Incra or those who have made a rival claim to the property.

After Unearthed contacted Serabi, it released a statement to investors acknowledging that the Coringa land “has been subject to various challenges over the years.” The statement did not mention the settlement, and claimed Incra had yet to “determine the legitimate title holder”. It said “payment will be made to the appropriate title holder as and when title is formally confirmed.”

Matias said that they had applied to Incra for official titles three times and had been rejected each time, because of the settlement. Both Neto and Matias live in Salvador, in Bahia state, 2.800 km away from Coringa’s area.

Serabi is not the only company creating enclaves inside settlements in Pará. In 2021, Incra made a R$1,3 million deal (£207,000) with the Canadian miner Belo Sun to install an open-pit gold mine in a settlement where 600 families live. A few weeks later, former President Jair Bolsonaro issued a ruling allowing the land agency to sell areas in settlements to mining companies.

Serabi is reportedly citing this ruling to request Incra approves the Coringa project. Incra told Unearthed the request is being analysed but confirmed in an email that “to date, Incra has not authorised research and mining operations in the PDS Terra Nossa”. Serabi says they have been in “regular contact with Incra since acquiring the Project in 2017.”

“Chapleau recognizes as the owner of the area a guy who grabbed public land using fraud,” said da Silva. “It wants Incra’s consent but refuses to recognize the settlement.

The licences battle

Illegal land grabbing is not the only controversy linked to Serabi’s Coringa mine. Serabi failed to adequately consult the Kayapó Mekrãgnoti community, which lives in the Baú Indigenous territory seven miles away, before beginning to explore, alleged Brazil’s public prosecutor (MPF). The public prosecutor began court proceedings to stop the mine in 2017, citing the pollution risk posed to the Curuá river which flows through the Baú TI. For the Kayapó, the prosecutor argued, the river provides “great aquatic biodiversity, on which the indigenous people depend for their survival, in addition to the use of the spring for their entire traditional life cycle.”

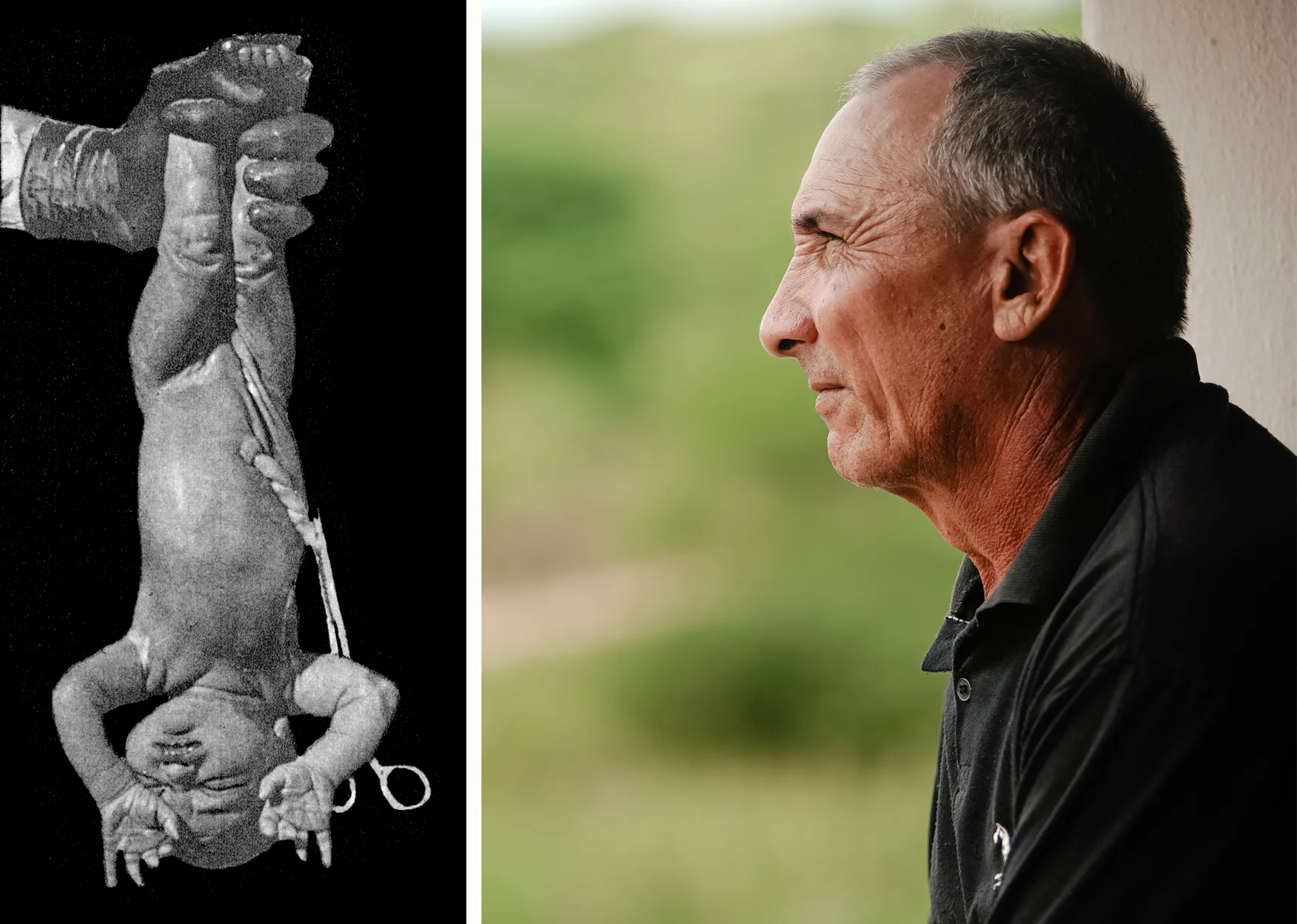

CACIQUE KUEI KAYAPÓ PASSES ON DEMANDS TO THE PUBLIC PROSECUTOR’S OFFICE’S TEAM DURING A MEETING IN THE MEN’S HOUSE, IN THE KAMAÚ VILLAGE, IN 2018. PHOTO: HELENA PALMQUIST/ PUBLIC PROSECUTOR’S OFFICE FOR THE STATE OF PARÁ

In December 2021 the TRF-1 (a high court based in Brasília) ruled that Pará State Environmental Secretary, Semas, and the National Mining Agency, ANM, should “refrain from granting any licence or authorisation to the Coringa Project” until the company concluded a consultation to the Indigenous population.

Despite this, both agencies renewed Coringa’s licences last August. ANM also said its licence was renewed “automatically” but that expired on February 7 and had not been renewed again after that date, due to the court decision: “There is no current authorisation for mining in these areas.”

Serabi’s recent statement to investors declared it had commissioned an Indigenous Impact Study at the beginning of 2022 and would present the final report for review “in the next few weeks.”

“Whilst progress has been slower than we were originally led to believe, the final report is expected to be available to be presented to the authorities for their review in the next few weeks,”, CEO Mike Hodgson said.

The company also said that it planned to continue processing ore at a different site, and had decided any future tailings storage at Coringa would be “dry” which ought to “minimise any concerns of the communities that are dependent on the Curuá River regarding the potential for pollution.”

The MPF told Unearthed the renewed licences were in “direct violation of the judicial decision” and said it would begin proceedings to shut down Serabi’s operations at Coringa. If the high court concludes ANM and Semas disobeyed its ruling, the agencies may face a fine of R$50,000 (£7,960) per day of non-compliance.

Felício Pontes Junior, the public prosecutor who has been accompanying the case in the high court, said:

“I hope that there will be an exemplary punishment to this company and that this will serve as an example to the other mining companies, especially the foreign ones, which today settle in the Amazon without respect to the basic rights of the traditional peoples.”

Serabi shows no signs of slowing down. According to public reports, 1,013 ounces (28.7 kg) of gold were extracted from Coringa’s mine in 2022. Once in full operation, the company expects to reach 38,000 ounces (over 1,000 kg) per year at Coringa, worth about US$ 70 million. Combined with facilities elsewhere, this would double the miner’s current total annual production.

However, Serabi says that under Brazilian law the licenses are automatically extended as long as renewal applications have been submitted. In an update published last month, they said: “The company confirms that renewal applications have been submitted within the stipulated time frames and that no notifications have been received from the issuing authorities that renewal will not be approved. Accordingly, these licences, which had an initial expiry date of 8 August 2022, remain valid.” They also state that they have been in regular contact with INCRA over the issue of land permits.

The company seems buoyant about the mine’s prospects, although in an interview in November last year, Hodgson said the mining industry was “a little bit disappointed” with President Lula’s electoral defeat of Bolsonaro. He commended Bolsonaro, who has been broadly condemned for encouraging exploitation of the Amazon by miners and farmers: “Whatever people think of him outside Brazil, [Bolsonaro] has been great for the infrastructure and the mining industry as a whole”.

In an email, Serabi said it “operates and complies with the Brazilian legal mining framework, we have all the required permits for our trial mining operation at Coringa and we are completely comfortable with our legal position and behaviour in relation to the ongoing disputed land ownership within which Coringa sits. Serabi has been operating in Para State for over 20 years and remains committed to working with all stakeholders, supporting local communities and operating in an environmentally sensitive manner.”

*This report was produced by Unearthed, Greenpeace’s research unit in the United Kingdom, in partnership with SUMAÚMA and The Guardian.

Translation into Portuguese: Denise Bobadilha

Translation into Spanish: Meritxell Almarza

Photography editing: Marcelo Aguilar, Mariana Greif and Pablo Albarenga

THE KAMAÚ VILLAGE IS THE OLDEST OF THE FOUR VILLAGES OF THE BAÚ INDIGENOUS LAND, WHICH IS LOCATED IN THE STATE OF PARÁ. PHOTO: HELENA PALMQUIST/ PUBLIC PROSECUTOR’S OFFICE FOR THE STATE OF PARÁ