Chapultepec Forest is one of the largest urban parks in the world and a space revered for centuries by the inhabitants of Mexico. For pre-Hispanic peoples, ‘The Chapulín Hill’ or ‘Grasshopper Hill’: was a means of communication with the gods and a source of natural resources, a promise for the future. And it still is. In the most populated city in North America, the forest is a collective refuge and a place of individual pilgrimage, a space that reminds us that life is still possible in spite of everything

It was at the end of 2019 when they made the map that led me to the entrance of the underworld. China had not even reported the first outbreak of atypical pneumonia in Wuhan, but some things are born destined for the future: the map of the best places to cry in public in Mexico City, a kind of cartography of catharsis, created using the suggestions of hundreds of Twitter users, came to me in mid-2021, when we were more than a year into the pandemic and North America’s most populous city was incubating a third wave of cases. Everyone seemed to be at breaking point in those days. The map had 54 georeferenced sites and 8 of them were in the Chapultepec Forest. It was totally logical: for months now, the forest had been the territory that potentially sustained the mental health of thousands of people, including myself.

After the waters of the volcano: Chapultepec and its surroundings have been inhabited by humans for over three thousand years

I now know that there is a battery of scientific studies showing that being among trees reduces the levels of cortisol in saliva – a physiological indicator of stress – lowers adrenaline, lowers blood pressure and lowers heart rate. I read that the air we breathe in the midst of vegetation is populated with monoterpenes – a volatile organic compound emitted by plants to communicate and interact with insects and animals – which are studied for their anti-inflammatory, anti-tumorigenic and neuroprotective properties. An expert in health architecture found that simply looking at images of nature is enough to activate our parasympathetic nervous system, responsible for generating a state of rest that allows us to recover energy. But none of that was what brought me to the Chapultepec Forest at the beginning of 2021; rather it was the need to escape from myself, from the accumulated weight of uncertainty. I went looking for a way out and found what you get from the ocean: perspective. The forest did not reduce my problems, but my own importance. Then I started going almost every week, almost every day, and I never stopped.

Faced with the magnitude of the Chapultepec Forest, the idea that the end of your plans coincides with the end of the world becomes ridiculous, pure solipsism. It is like an arrow piercing a tiny, childlike heart carved in the bark of a tree that has lived more than five centuries (forest technicians estimate that it has trees up to 600 or 800 years old). Chapultepec Hill – the most commonly used formula to translate Chapultepec from Nahuatl – is the origin of one of the ten largest urban parks in the world – twice the size of Central Park – but it also contains more than three thousand years of history. It has marked the origin and life of this city in so many ways and for so long that it is only possible to grasp something of its significance through enumeration or grandiloquence.

Enumeration: in 2005, an internal publication of Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History described Chapultepec as “a forest of hundred-year-old Montezuma cypresses, an area of springs, a place to read the sky, a garden for vice-regal revelry, a battlefield, an imperial site, a public park where all dreams have a place, a site of discussion and discord, and why not, a disputed commercial zone”. A small city within the city, its director, Mónica Pacheco Skidmore, will later tell me. “Like a Vatican.” Grandiloquence: as if the Vatican had given birth to Rome.

‘Grasshopper Hill’: is a volcano from which water flowed. A volcano that flourished. A volcanic cone formed millions of years ago

Chapultepec Forest is the second most visited place in the Mexican capital after the Basilica of Guadalupe, says Pacheco: “It has an average of 23 to 24 million visitors a year”. Some of them, according to the map of recommendations for public catharsis, instead of taking their pain to church, prefer to take it to the Audiorama, a corner of the forest that was inaugurated in 1972 as a space for reading. “To arrive at this place is to reach the sacred heart of the great forest, it is to receive the gift of reconnecting with peace and inner balance, feeling the embrace of the mother. Thank you, thank you, thank you to my ancestors,” reads an unsigned comment in the notebook at the entrance of the Audiorama. “It lets me see other things that I still struggle to understand,” Juana wrote in June of this year. “If being with my friends was a place, this would be it.” That was a visitor who signed in as Giyo. “I’ve seen many, many people cry here,” says Carlos Hernández y Cervantes, an 83-year-old gardener who has worked in the forest for half his life, and since 2009 has been the caretaker of this place.

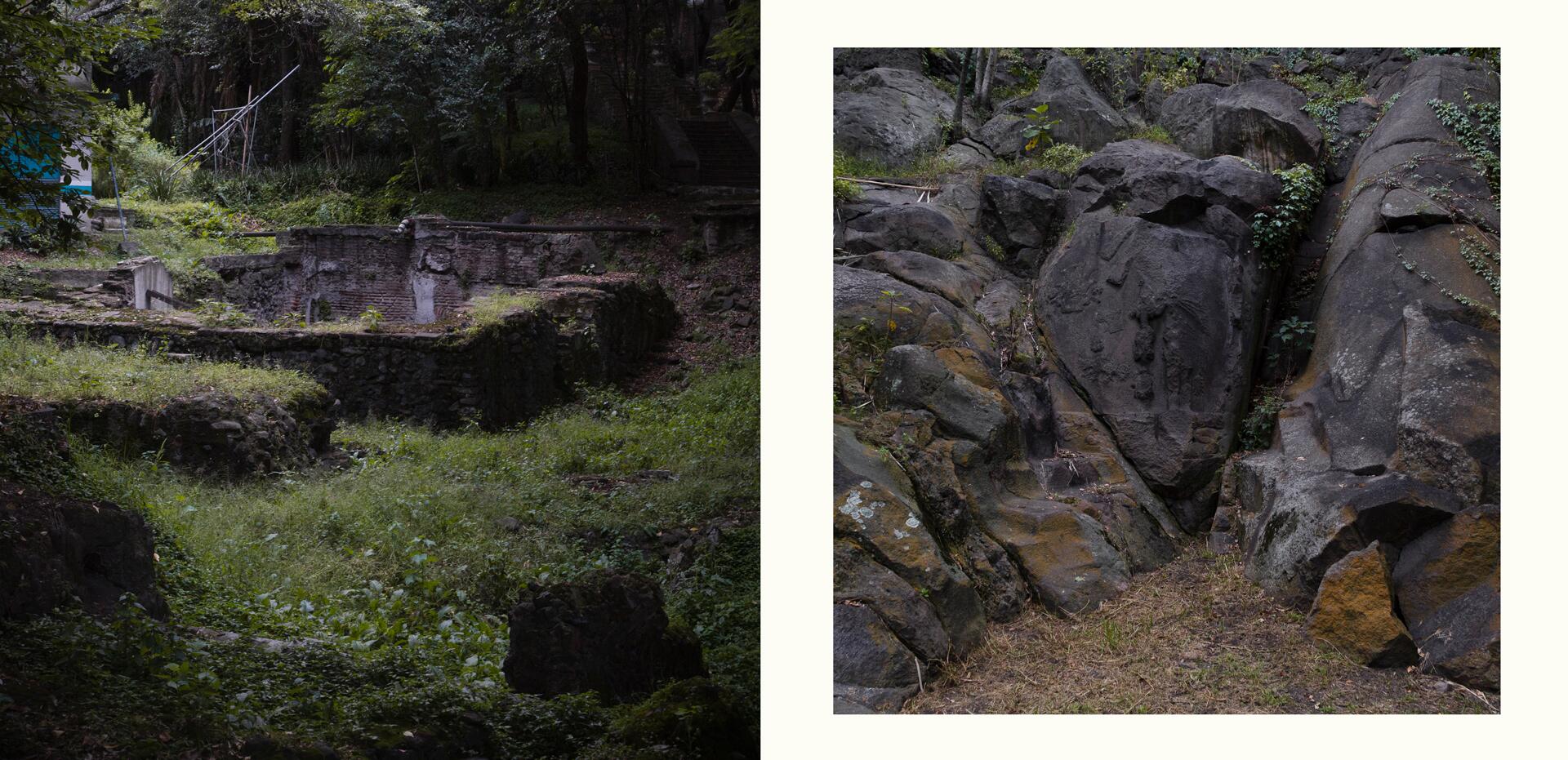

“Here” is this: a kind of cleft that opens at the base of an extinct volcano -that’s how Chapulin Hill was formed-, a horseshoe-shaped space enclosed by towering trees and bamboo and volcanic rock, all green and shaded, so that it gives the sensation of being in a clearing in the middle of a mountain, in an open-air grotto. There are colorful benches to sit on, there is a floor of small clear pebbles and, at one end, there is an entrance to a cave guarded by a fence. “People are asked to humbly approach the fence and do some meditation,” explains Carlos. To free them from the burden they carry. Because that stone opening behind the grille leads to what is known as Cincalco Cave, a sacred site for pre-Hispanic peoples such as the Toltecs and the Mexica, an entrance to the underworld (the place of the dead in Mexica mythology); the place where Huemac, the last ruler of the Toltecs, went to die.

According to a codex used as a historical document, Huemac took refuge in the cave of Cincalco and hanged himself. According to another version, he just went into the grotto and never came out again. The reasons that led him to take shelter inside the hill are part of an extended legend, one with a moral, that links that past with this future. The story goes that Huemac played a ball game with the Tlaloques – the little helpers of Tlaloc, the rain god – in which they wagered jade stones and quetzal feathers. When the Toltec king won, the Tlaloques went to pay him with “elotes (green corn cobs) and the precious green corn leaves in which the corn grows”. Huémac rejected them and demanded to be paid what he was entitled to: the green jade stones, the green feathers of the quetzal. Tlaloc’s helpers resigned themselves and gave him what he asked for, but condemned his people to suffer for four years: they received hailstones so copious that the ice reached up to their knees, their crops failed, and they suffered droughts so severe that rocks melted. The Toltecs were starving to death. Tlaloc demanded a sacrifice and returned to give them rain, but first he let Huemac know that the end of his time was near, that the time of the Mexica was coming. We already know how it ends: Huemac went to Chapultepec, took refuge in the cave of Cincalco and never reappeared, while the dispersion and ruin of his people ensued.

Cincalco Cave: Carlos Hernández y Cervantes, 83-year-old gardener, has worked in the forest for half his life and since 2009 has been guarding the entrance to the underworld

Nature’s lessons are not subtle; they just take their time.

***

Behind the grille that protects the access to the grotto, a few steps into the darkness, there is always a candle burning. Not everyone who comes to the Audiorama knows the legend of the Cincalco cave, but everyone ends up coming to look at that stone mouth that sinks into the hill. “Being here, they’re moved by the energy,” the gardener tells me matter-of-factly. Visitors repeat that word in their comments: “I love the energy of this place”. Anyone who has wandered in the forest long enough to cut, even for a moment, the wires that connect him to the urgency of the world, is able to understand how easily admiration can become veneration; and the thin line that separates gratitude from mysticism. “One would think that we are going towards a modernity that is turning its back on that,” biologist Martín Aguilar Cervantes, the forest’s deputy technical director, will tell me later. But no: “These groups of tree worshippers, rock worshippers, cave worshippers are coming back,” he says.

For the deputy director, it is an adaptation “of some beliefs in the natural forces that they want to find here in Chapultepec”. And, of course, they do find them.

The pre-Hispanic engravings were destroyed: by the church in the 16th century, mining activity in the 18th, American bombing in the 19th, and by time

Chapultepec is a volcano from which water flowed. A volcano that flourished. A volcanic cone formed millions of years ago that, “having a lateral fracture, caused cold water to gush from its springs,” details in one of her articles the archaeologist and scientist María de Lourdes López Camacho, one of the greatest experts in the history and significance of this region. Over time, this condition led to “dense vegetation and fauna inhabiting the foothills”. López Camacho explains that almost all societies in the world have venerated mountains; in Mesoamerica, this cult was linked to agriculture and the plea for rain: “Elevations were conceived as one of the means of communication between man and the gods, consequently, mountains were recognized as sacred places and places of sustenance”. The Chapulin hill was sacred to the pre-Hispanic peoples because it was a provider of life, like Tlaloc, who dominated over the rain and the hill, the water and the vegetation: for the richness of its flora and fauna, for the springs that were born from its slopes, for its natural resources. For this reason, throughout history it has also been a desired, protected, intervened and disputed space.

The life of Mexico City has been inseparable from Chapultepec for centuries: its springs supplied water to Tenochtitlán, the ancient Mexica capital, through a series of reservoirs, aqueducts and canals. During the siege of Tenochtitlán, the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés ordered the aqueduct that supplied the city with fresh water from the springs on the hill to be cut, a key strategy to bring it down. In Chapultepec temples were built to the tutelary deities of water, sacrifices were made, purification ceremonies were held in its waters and Aztec kings bathed in it, gardens and zoos were established. “In both pre-Hispanic and viceregal times,” writes López Camacho, “Chapultepec was an object of pilgrimage and worship; the sovereigns had their residence in this place and built temples or palaces, roads, hydraulic systems.” No one in history seems to have been indifferent to its natural wonders or its beauty, although for us it seems easier to forget it.

In a book that brings together different perspectives on the forest, conservationist Vance G. Martin recently wondered why Chapultepec could not be considered a sacred zone again, “since it is both the heart and the lungs of Mexico City.” The experiences offered by forest areas, particularly the most intact ones, he wrote, “can remind us that, despite the traces of human civilization and infrastructure, nature remains the highest authority.” Chapultepec Forest today covers some 800 hectares – divided into four sections – but you don’t have to go far in search of a wild corner to be reminded of its significance. Sometimes all it takes is a disaster, a sense of unease, whatever it is that interrupts our rat race and pushes us out of our cubicles to get there.

The Chapultepec lakes: were built at the end of the 19th century on concrete-filled mines. Carp, which are actually an exotic species, has become a pest and threatens the native fauna

“Thousands of tired, nerve-shaken, over-civilized people are beginning to find out that going to the mountains is going home,” wrote Scottish naturalist John Muir, founder of the first conservation group in history, more than a century ago. The difficult thing, in a city where more than twenty million people travel daily, is to know what each person understands by home.

***

Roberto Ramírez, head of maintenance at Chapultepec Forest, vaguely recalls that it was around the time of the World Cup in Germany. As he remembers it, the warning came when Mexico was playing Portugal, although it was actually a few weeks earlier. What he does remember precisely is that no one was prepared for something like this: the Lago Mayor, or great lake, in the second section of the forest was emptying. “The Chapultepec lake broke,” read the news published in La Jornada on June 6, 2006. A day earlier, 50,000 cubic meters of water – about a quarter of the lake’s total liquid – had suddenly seeped underground in a matter of minutes, exposing a mud slick in which hundreds of carp were dying. “The lake is located in an area that was formerly mines,” Ramirez explains. “As its bed is concrete, we believe there was a leak and it was undermining the soil until it was unsupported.” The first thing they did was to build a dam to stop the spill and prevent the animals from continuing to leave. “There were fish, ducks, axolotls, smallmouth silverside fish.” The second was to invent methods of rescuing the remaining fauna: they used tarpaulins to improvise pools in trailer trucks, and so they were able to move them. Thirdly they cleaned the bottom of the lake, which was covered by a thick layer of mud. “We even found a car there,” Ramírez recalls. “A vochito” (a Volkswagen Beetle). From the mud they pulled out “firearms, dentures, an infinity of glasses, coins… Like a museum”.

It took months to clean, repair and refill the lake. But the living beings and the inert objects that came to the surface were drawing a plot more complex to solve than the water filtration: the set of conflicting interests that cross a collective territory such as the forest, which each inhabitant feels belongs to them.

When the lake began to empty, reports say that dozens of people waded into the mud to try to rescue the carp, which are actually an exotic species that has become a pest and threatens the native fauna. Today, 17 years later, they are still a problem in the forest lakes. The question is how they appeared there. “People bring them,” says Ramírez. They bring tilapia, he says, which are predators; they bring turtles, “which should not be there”; they being white ducks, “which are very aggressive and inhibit the arrival of migrant ducks”. At the end of 2022, Mexico City’s Secretariat of Environment created a group of experts to improve conditions in the forest lakes. They announced that the project aimed to incorporate a “citizen science” approach, so that neighbors could participate in the monitoring.

A change in temperature: inside the forest, the body is subjected to less thermal stress. Just as it dampens the heat, it dampens noise and wind speed

The sense of belonging is a double-edged sword, but in some cases it is unavoidable. Part of the population of Mexico City, the deputy director of the forest will tell me later, is native fauna of the same forest. Although he doesn’t say it that way: “I think there is an important percentage of the population, especially of the capital, that came from here, from the Bosque de Chapultepec, or at least came to make plans and emerged from here,” says Martin Aguilar. Not that there are statistics. But “there are many anecdotes of anyone you ask, who came to start a relationship in Chapultepec”. A generalization based on empirical cases, “which can give an idea of how socially important the forest is”.

The Mexican painter Teresa Velázquez, who often defines herself as a “native of San Miguel Chapultepec” – a traditional neighborhood located south of the forest, where she grew up and where she lives today, in the same house her grandfather bought – has a deep-rooted bond with the forest that unites many of those who spent their childhood there and those who currently live in the surrounding area. Some years ago, she says, when she was riding her bicycle inside Chapultepec, she called her daughter, who was then living in New York, and told her: “Don’t tell anyone, because the day they find out they’ll immolate us, but this forest is much more interesting and important than Central Park”. In the end, he says, two years later it happened: the Chapultepec, Nature and Culture project was presented, coordinated by artist Gabriel Orozco. A project considered a “priority” by the government, which has led to the expansion of the forest territory and includes environmental, forestry, infrastructure and cultural initiatives. That plan, which has been mutating since it started, which had a break during the pandemic and has unleashed multiple questions, also prompted the creation of the Citizens’ Front for the Defense of Chapultepec Forest, of which Teresa Velázquez is a member.

Artificial wetlands: several species of flora and fauna coexist. Nearly 200,000 trees maintain Chapultepec’s microclimate

The Frente Ciudadano managed to put a stop to the Contemporary Art Pavilion, for example, one of the works proposed by Orozco, which neighbors and activists denounced as it would overshadow the botanical garden and the orchid garden that currently exist in Chapultepec, a space where there are already a dozen museums. It is not that the rejection of the large project has been monolithic: at first, says Velázquez, the idea of recovering the watershed that runs through the forest excited many of them. But no one besides the promoters seemed to agree with a work that they attributed to the megalomaniacal zeal of an artist rather than to a real necessity. The forest has not ceased to be a coveted and disputed space, a territory crossed by power conflicts that bears the traces of adaptation and survival, and that embodies one of the most emblematic dilemmas of this era: that of the meaning we give to the word “progress”.

***

Since 1530, when Emperor Charles V decreed, by Royal Decree, that Chapultepec Forest should become the property of Mexico City, it has been under the administration of the Mexican capital, but “it has had many temptations,” says its executive director, Monica Pacheco: the temptation of bureaucrats or officials who want to appropriate spaces, she explains, “when sometimes we don’t understand that we are temporary”. For Pacheco, the forest is “the most democratic, most popular and most civic space” in the capital. Here converge, she says, everyone from the richest man in Latin America (Mexican businessman Carlos Slim) “who has come to walk among the hundred-year-old Montezuma cypresses here by the lake”, to an ex-convict who, on his first day of freedom, chose to go to Chapultepec “to feel completely free”.

The forest city is populated by communities, says Pacheco, and those communities are what make Chapultepec what it is. The forest itself is, in biological terms, a set of communities: the most appropriate way to think of a tree, a cactus or a shrub, explains the Italian botanist Stefano Mancuso in his book Sensitivity and Intelligence In The Plant World, is not to compare it to a human being or any other animal, but to imagine them as a colony. “A tree, then, is much more similar to a colony of bees or ants than it is an individual animal.” German forest scientist Peter Wohlleben sums it up: “A tree can be only as strong as the forest that surrounds it”.

The Chapultepec Forest has about 200,000 trees and does justice to the idea of refuge. It is an island of vegetation in a sea of concrete. In some areas, the density of its trees is so high that it generates microclimates. Leaving the street and plunging into the forest involves, in fact, a change in temperature: inside, the body is subjected to less thermal stress. Just as it dampens the heat, it dampens noise and wind speed. It is a source of carbon capture and one of the main regulators of air quality in the Mexican capital. The trees filter rainwater into the soil and maintain the hydrological cycle. It is also a haven for migratory birds. And, for “our savannah-bred brains,” as author Florence Williams wrote, it’s a way to come home.

Early on in the pandemic, when no one had a clue what was going on, but people demanded that the authorities make decisions as if they knew, the forest was closed for three months. “It was a mistake to close,” the director said. “We learned that. This is a space of freedom.” At one point, she tells me, it was decided that everyone over 60 who worked there should go home. They practically had to force them to leave, she recalls. “What’s more, they had more health problems there than here.”

The naturalist John Muir, who could have quietly left a comment in the Audiorama guestbook, said the same thing more than a century ago: “Few places in this world are more dangerous than home. Ear not, therefore, to try the mountain passes. They will kill care, save you from deadly apathy, set you free.” Huemac understood it a thousand years ago: there is nothing more useless than precious stones if you do not have rain. For us – for some, for many – it took a pandemic, a loss of meaning, a test of the fragility of our certainties, to push us to the edge of the forest.

***

Eliezer Budasoff (Argentina, 1978). Director of new podcast development at Radio Ambulante Estudios, where he is also host and editor of the podcast El hilo. He was editor of special projects at the newspaper El País, editorial director of The New York Times en Español and editor of the magazine Etiqueta Negra. He won the Gabo text prize in 2021 and the Las Nuevas Plumas chronicles award in 2011.

This story is part of the Colapso project by Dromómanos, an independent news producer based in Mexico.

About Dromómanos

Dromómanos is a producer of independent journalism that investigates, educates and experiments to tell the story of Latin America in collaboration with journalists from all over the region. The project began in 2011, when its founders Alejandra S. Inzunza and José Luis Pardo Veiras traveled across the continent in a third-hand Volkswagen Pointer in a bid to forge a new journalistic model of continental coverage. Together they have created more than 20-long form reportages and Narcoamérica, a book documenting the impact of drug trafficking on everyday life in societies throughout Latin America. In the past 12 years, Dromómanos has worked with over 100 contributors and partnered with 60 national and international media outlets to address the most pressing issues for Latin Americans, such as violence, the climate crisis, authoritarianism, migration and corruption.

About the Colapso project

What happens when the power of nature intersects with human suffering? In few places can one find a more striking answer to this question about our present and future than in Latin America, the most disparate and one of the most biodiverse regions in the world. Colapso ventures deep into the jungles, mountains, islands, forests, deserts, oceans and cities of the region, to report from the field on the symptoms and consequences of the climate crisis.

Text: Eliezer Budasoff

Photos: Felipe Luna Espinosa

Fact check: Dromómanos

Spell check (portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Translation into portuguese: Paulo Migliacci

English translation: Charlotte Coombe

Visual editing and page setup: Viviane Zandonadi, Lela Beltrão, and Érica Saboya

Director: Eliane Brum

Mexica culture: Chapultepec was the place where Tlaloc and Chalchiuhtlicue, the gods of water, lived