Nine years after the start of the environmental licensing process for offshore oil exploration at the mouth of the Amazon River, the federal government has finally started to consider the consequences for the 8,000 or so indigenous people of Oiapoque, the northernmost coastline of Brazil. This is late, but the fact that it is being done at all is thanks to the determination of the four native peoples in this region of Amapá State – Karipuna, Palikur, Galibi Kaliña and Galibi-Marworno – to be consulted about plans to drill in the so-called Block 59, which was taken over by Petrobras two years ago, after its partner, the British company BP, withdrew. In an extremely socially and environmentally sensitive area, the state-owned company aims to open a “new frontier” of oil exploration that goes against President Lula’s environmental commitments, as shown in a report published in February by SUMAÚMA.

In their first meeting with a team from Petrobras, on February 13, three of the indigenous communities – Uaçá, Juminã and Galibi – complained about daily helicopter flights between the airport in the municipality of Oiapoque and the exploration ship sent by the state company to Block 59 in December, when Petrobras was expecting the operating license to be issued. Flying at a low altitude, they scare away wild ducks, Jabiru Mycteria storks – the tuiuiú popularized by the soap opera “Pantanal” – and other birds, as well as the game that the villages need for food, handicrafts and ritual practices. The indigenous people said they had not been warned in advance of this activity, “which is even disrupting the tranquility of the communities.”

In addition, they asked Petrobras to get more involved in decision-making regarding moving the Oiapoque rubbish dump, which is close to the municipality’s small airfield. A 2009 court decision had determined the construction of a suitable site, but this has become more urgent as a result of the state-run company’s flights. The town hall’s original plan was to build a sanitary landfill close to two villages, which posed a contamination risk to water sources.

In early March, Ibama (the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources), responsible for environmental licensing, asked Petrobras to include the question of flyovers in the project’s Environmental Impact Study and to present “mitigating measures”, given that these impacts “will be continued” if the operating license is granted. It also suggested a “higher level assessment as to the appropriateness of forwarding the process for a declaration” from Funai, the National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples. In the case of Oiapoque’s airport, the institute’s technical report published on March 6 agrees with the indigenous people when they assert that Petrobras should not be exempted from responsibility for the results of the remodeling it is sponsoring at the facility, bearing in mind that, if it were not a support base for the company’s activities on the Amapá coast, this would not be happening.

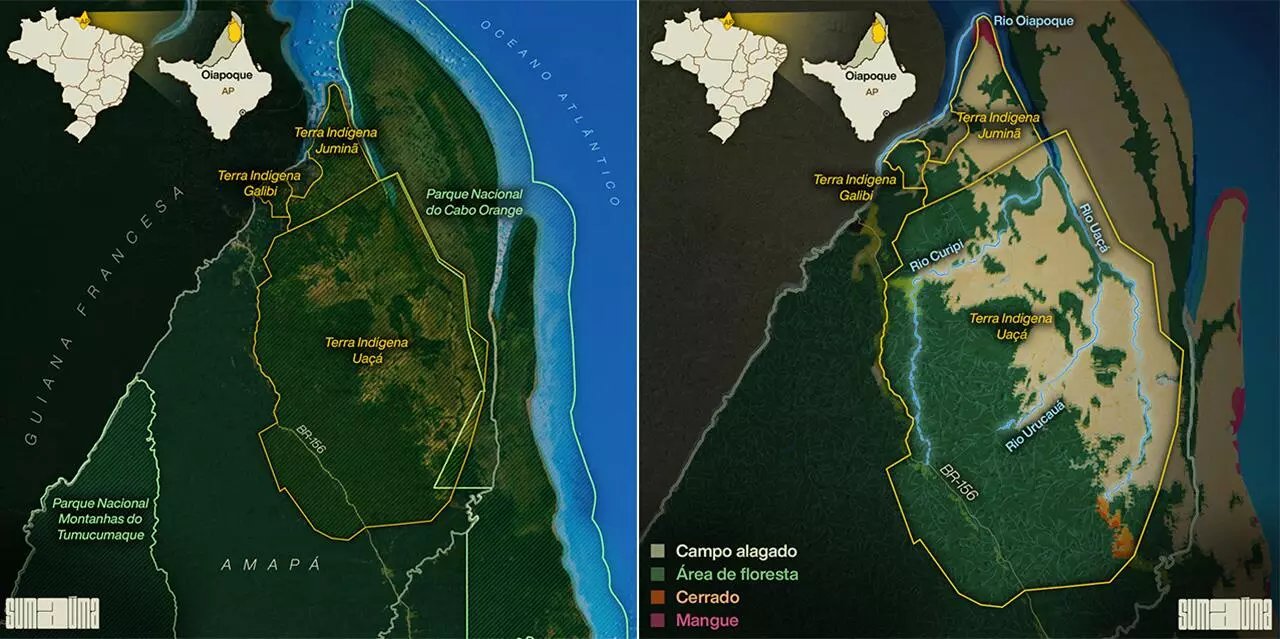

Os mapas acima mostram as três terras indígenas que correm risco se as atividades de exploração de petróleo na costa do Amapá forem autorizadas. A imagem da esquerda destaca os territórios. À da direita exibe a cobertura vegetal e a hidrografia da região. Infografia: Rodolfo Almeida/SUMAÚMA

In their first meeting with a team from Petrobras, on February 13, three of the indigenous communities complained about daily helicopter flights between the airport in the municipality of Oiapoque and the exploration ship sent by the state company to Block 59 in December, when Petrobras was expecting the operating license to be issued. Flying at a low altitude, they scare away wild ducks, Jabiru Mycteria storks – the tuiuiú popularized by the soap opera “Pantanal” – and other birds, as well as the game that the villages need for food, handicrafts and ritual practices. The indigenous people said they had not been warned in advance of this activity, “which is even disrupting the tranquility of the communities.”

In addition, they asked Petrobras to get more involved in decision-making regarding moving the Oiapoque rubbish dump, which is close to the municipality’s small airfield. A 2009 court decision had determined the construction of a suitable site, but this has become more urgent as a result of the state-run company’s flights. The town hall’s original plan was to build a sanitary landfill close to two villages, which posed a contamination risk to water sources.

In early March, Ibama (the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources), responsible for environmental licensing, asked Petrobras to include the question of flyovers in the project’s Environmental Impact Study and to present “mitigating measures”, given that these impacts “will be continued” if the operating license is granted. It also suggested a “higher level assessment as to the appropriateness of forwarding the process for a declaration” from Funai, the National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples. In the case of Oiapoque’s airport, the institute’s technical report published on March 6 agrees with the indigenous people when they assert that Petrobras should not be exempted from responsibility for the results of the remodeling it is sponsoring at the facility, bearing in mind that, if it were not a support base for the company’s activities on the Amapá coast, this would not be happening.

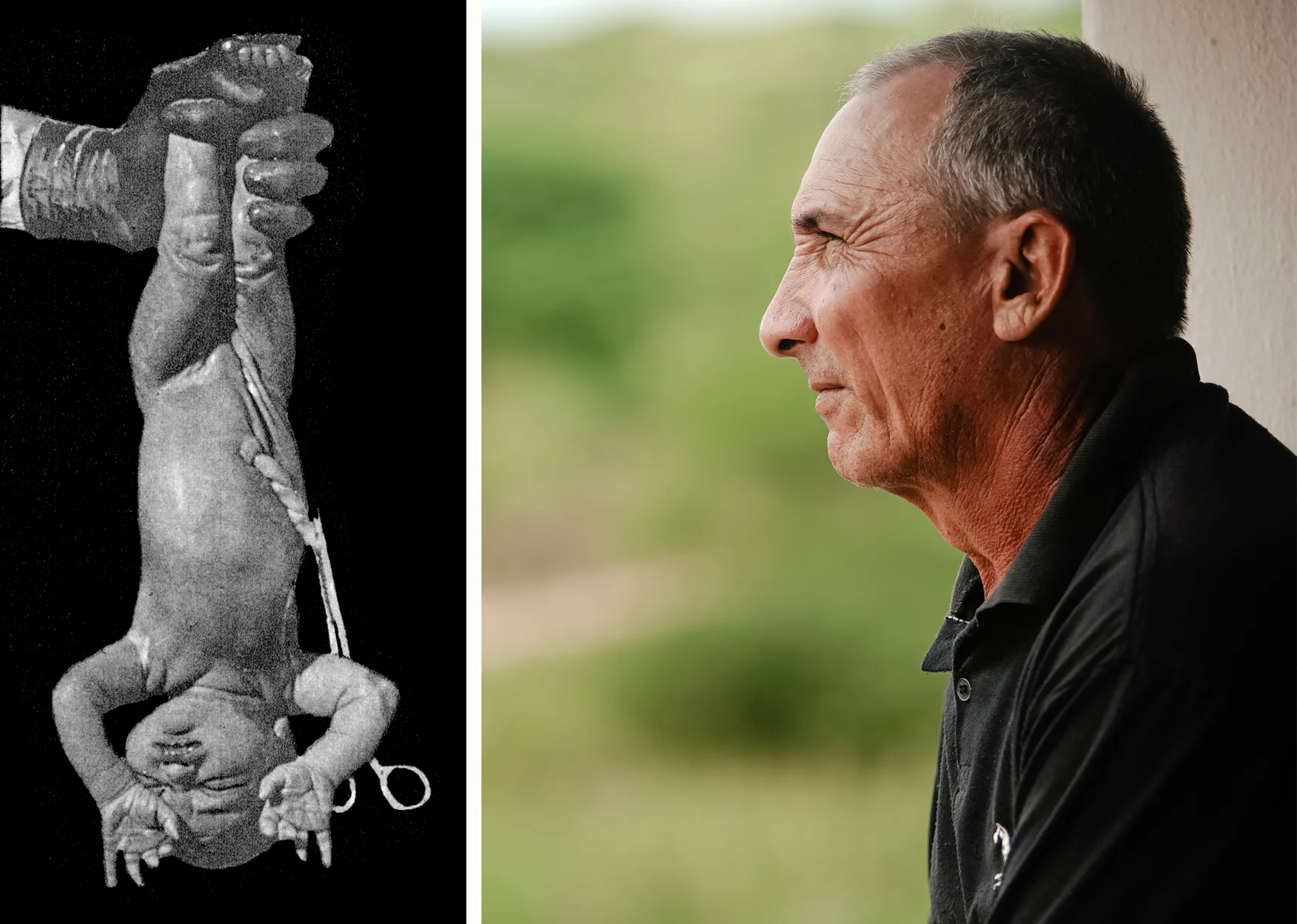

Macaco em árvore na floresta da costa do estado do Amapá, no extremo norte do Brasil. A exploração de petróleo em alto-mar ameaça comunidades tradicionais, povos originários e o ecossistema da região cheia de mangues, florestas tropicais e recifes da foz do Amazonas. Foto: Victor Moriyama/Greenpeace

It was the first time the demands of indigenous people were included in an Ibama document in the case of block 59, albeit at an advanced stage in the licensing process. The simulation of an oil spill accident is expected to take place before the end of this month, perhaps as early as March 20. If Petrobras is approved by the so-called Pre-Operational Assessment (APO), this is considered the last stage before the license for prospecting is issued. However, in an interview given to SUMAÚMA, Ibama’s new president, Rodrigo Agostinho, said he will analyze all the recommendations made by the institute’s technicians before making any decision, and this could take weeks.

A aldeia Kuhaí durante a 29ª Assembleia de Caciques dos Povos Indígenas do Oiapoque, que aconteceu de 11 a 14 de março. Foto: Maksuel Martins/Secretaria de Comunicação do governo do Amapá

Through its press office, Petrobras said it is changing the route and altitude of flights between Oiapoque and the exploration vessel, but their frequency will continue to be two flights a day, from Monday to Friday, if it gets the license. It argued its operation “is within the installed capacity of the airport,” which is authorized to transport 200,000 passengers a year. It said “it is contributing to studies” to determine the sanitary landfill’s location, and “the expectation is” for public authorities to consult with indigenous people as to the best solution.

For now, the indigenous leaders are satisfied they have managed to get Petrobras to discuss the issue in their own territory – the meeting was held on Uaçá land, at the Domingos Santa Rosa Training Center, named after a former indigenous leader of the region and Funai employee, who died in 2020. In November last year, the caciques refused to go to a public information meeting organised by the company at the municipality’s headquarters. They had asked for an exclusive meeting. The Oiapoque’s people were politically mobilised in the 1970s, and the first of the region’s three indigenous lands was ratified in 1982, at the end of the military-business dictatorship (1964-1985). The local indigenous people hold an annual general assembly, famous in Amapá – this year’s, the 29th, took place from March 11 to 14, in the Kuhaí village, discussing public policies in areas such as education, health, culture, and agriculture. For a long time they have been organized into entities such as the Council of Caciques of the Indigenous Peoples of Oiapoque (CCPIO) and the Association of Indigenous Peoples of Amapá and of the North of the State of Pará (Apoianp). In 2019, they launched a request under the prior consultation protocol, provided for in Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization (ILO), signed by Brazil and incorporated into the country’s national legislation.

“It was an excellent meeting, we asked our questions, and they seemed to be responsive to our concerns. We made a proposal to set up a working group, and we were very firm in our request that the consultation be made and the protocol adhered to, so that our needs could be met and our concerns clarified. We do not have any experience in dealing with a large multinational company, such as Petrobras, but we were able to get our message across, and obtain important information that we wanted to hear. We are satisfied with the initial conversation”, said Edmilson dos Santos Oliveira, who is the chief of the Karipuna people and coordinator of the CCPIO, over the phone.

In all, 78 people signed the attendance list of the meeting, which lasted a whole day, and included an informative session given by Petrobras along with speeches by indigenous people, who accounted for the majority of those present. There were representatives from Funai, Ibama, the Public Prosecutor’s Office and organizations with local operations, such as WWF and the Indigenous Research and Training Institute (Iepé). Petrobras turned up with a sizeable delegation of 13 people, including Daniele Lomba, its Licensing and Environmental Compliance Manager, and Priscila Moczydlower, the social responsibility coordinator for Oiapoque, along with geologists and two recently hired anthropologists from a third-party company.

The indigenous people, who account for almost a third of the municipality’s 28,000 inhabitants, have had their fingers burned with two projects where their demands were not met: the BR-156 highway, which links Macapá to Oiapoque and led to the relocation of several villages and the Cafesoca hydroelectric power plant, which will dam a stretch of the Oiapoque river, one of the four largest in the region. Now, despite the caciques’ willingness to open up a dialogue, it was only at the end of the meeting that Petrobras admitted the flyovers were to take people and supplies to its exploration ship. With regard to prior consultation, the negotiation between the indigenous leaders and the company is complicated and full of verbal gymnastics. “The working group is a victory for the indigenous people, but it is not a consultation for the enterprise,” said Daniela Jerez, WWF’s representative at the meeting.

Helicópteros a serviço da Petrobras no aeroporto de Oiapoque, no Amapá. Indígenas relataram que os voos dessas aeronaves afugentam aves e a caça de que as aldeias precisam para alimentação, artesanato e práticas rituais. Foto: Felipe Gaspar/Divulgação

For a long time, since its projections did not envisage any direct impacts of oil prospecting on indigenous lands, Petrobras worked under the assumption that there was no need to comply with Convention 169. But this was demanded by the peoples of Oiapoque, and was the subject of a recommendation sent to the company last year by federal prosecutors in the States of Amapá and Pará. The state-run company is now saying the activity being licensed by Ibama is “temporary”, being expected to last five months. If it finds oil in Block 59, “it is possible it will become an enterprise. In this case, “a new licensing process will have to be carried out” – although it is known that once a license has been obtained for drilling, it is highly unlikely that a license for production will be denied. For the moment, the company said, the CCPIO consultation protocol will be adopted “as a reference for the relationship and construction of dialogue in an attempt to implement actions and partnerships that are in synch with the company’s activity.”

In February, for the first time, Petrobras included the presentation of projects for the States of Amapá and Pará, where the shipping base for the exploration at the mouth of the Amazon would be located, in the notice of its socio-environmental program. When asked if these projects, which have no direct relation with the company’s business, would be a way of obtaining support from indigenous people, the state-owned company replied that “earmarking social investments for areas surrounding our activities” was part of its social responsibility policy. “It is not a way of ‘garnering’ the support of communities; on the contrary, it is a way of boosting the positive impacts of our presence in a certain region and interacting with our neighbors,” said the company in a statement.

Either way, the caciques made it clear that they expect the consultation for the enterprise to take place, even if it occurs at some future date. “With the setting up of the working group, we will be able to better align the issue. They have shown themselves to be receptive and they are going to do the consultation, but have said that at this initial moment it is only a test, it is not yet an exploration, and that, if that occurs, if there is oil or gas there, then the situation will become a different one, and that is when the consultation will take place,” said Edmilson. For Hiandra Pedroso, Apoianp’s lawyer, Petrobras could already “be doing [the consultation], listening, verifying, carrying out a survey of the real social impact, and a prognosis of the safeguard plan for the future, if there is exploration. “That would also reduce their costs,” he said.

Daniela, from WWF, and Hiandra said that, at the meeting in February, the conflict between “academic knowledge and local knowledge”, between “the word of the non-indigenous and the traditional knowledge of the communities”, has resurfaced. Ever since the start of the licensing process for block 59, which is 160 kilometers from the coast, the projections for oil spills have made no provision for the oil slick’s arrival in the Oiapoque, a region of mangroves and swamps where the tide can be four meters high and the sea flows kilometers up the rivers during times of flooding. At the meeting, while the representatives of Petrobras emphasized the “solidity” of their studies and their experience in drilling deep-sea wells, a number of indigenous people drew on their practical experience to express doubts.

Ramon dos Santos, a leader of the Karipuna people, noted “70% of indigenous territory is water”, influenced by “tidal dynamics”, and that for this reason “he doesn’t know what could happen if there is an accident”. Maxwara Nunes, school director of the Galibi-Marworno people, spoke of the Cassiporé river, near the coastal area which has a “number of streams interconnected” to the Uaçá land. Chief Damasceno Fortes Karipuna said “any slick would indeed reach indigenous lands by means of the tide.”

Ramon suggested hiring indigenous environmental agents to monitor the enterprise’s impact, starting with the flyovers, and the cacique Nasildo Nunes suggested an “indigenous component” in Petrobras, “so the communities are aware of what is happening”. “We wanted to include some indigenous representatives within the Petrobras structure, in order to monitor and pass the information on to us in a clearer way, but they said it’s difficult, they didn’t really agree, maybe the sticking point is on the technical side. We explained there are indigenous people who are trained in a number of areas,” said Edmilson.

In the face of the questions, Daniele, the manager of the state-owned company, asked those present to talk about “positive impacts” Petrobras could bring to the indigenous peoples, and asked for proposals. Priscila, who is also from the company, mentioned a “range of options” in terms of consideration, talked about donating computers and training people, and gave details of the launching of a public notice for socio-environmental projects that includes the region. “One of the caciques said: if I don’t have good information, I may end up saying no to something that is good for me and yes to something that is not,” according to Daniela, from WWF.

One of the strongest demands was made by Priscila Barbosa Karipuna, the Apoianp’s leader. She pointed out there had been “failures right from the start of the dialogue process” and affirmed indigenous people “are not against any enterprise, but want the consultation protocol to be respected”. She said the delay in consultation is putting “pressure” on their leaders – one of the great concerns of Oiapoque’s native peoples is being accused of “holding back development” in the face of the expectations of employment and economic rewards the enterprise could bring to the municipality.

Although Petrobras stressed at the meeting that it currently only has a small team in the city, with 20 people, the company’s activities are often highlighted in the social media of the town hall, which is headed by Breno Almeida, who was elected in 2020 by the Brazilian Labor Renewal Party, which does not have any federal deputies but went as far as engaging in negotiations for Jair Bolsonaro to join the party back in 2021. On March 8, the city government reported on Instagram that the state-owned company had signed an amendment for renovation work at the airport. A day earlier, it gave an account of a talk about the Airport Emergency Plan “in the briefing room of Petrobras’ passenger terminal.”

Petrobras says there is no forecast of any direct job creation in the city, “given the activity is temporary,” but that if production occurs, “it is only natural that other opportunities will arise.” “We are aware of the local population’s expectations. This became clear in the expanded meeting held in Oiapoque in November 2022. At that meeting, we gave a commitment to structure ourselves together in order to promote social improvements by means of technical training,” said the state-run company, adding the public notice for socio-environmental projects allows local institutions and, therefore, local people to take part.

Simulated oil spill accident

While the clashes of interests play out in Oiapoque, the licensing process moves forward. On March 3, at a meeting between the state-run company’s representatives and the new person responsible for the General Coordination of Marine and Coastal Enterprises in Ibama, Itagyba Alvarenga Neto, it was agreed the simulated oil spill accident would be held this month, in principle on March 20. It was agreed the date would be confirmed at a later meeting.

Comunidade de pescadores na cidade de Calçoene, no Amapá. A Petrobras tem planos de explorar petróleo na costa do estado, colocando em risco o modo de vida de populações tradicionais e o ecossistema. Foto: Victor Moriyama/Greenpeace

Daniela, from WWF, and Hiandra said that, at the meeting in February, the conflict between “academic knowledge and local knowledge”, between “the word of the non-indigenous and the traditional knowledge of the communities”, has resurfaced. Ever since the start of the licensing process for block 59, which is 160 kilometers from the coast, the projections for oil spills have made no provision for the oil slick’s arrival in the Oiapoque, a region of mangroves and swamps where the tide can be four meters high and the sea flows kilometers up the rivers during times of flooding. At the meeting, while the representatives of Petrobras emphasized the “solidity” of their studies and their experience in drilling deep-sea wells, a number of indigenous people drew on their practical experience to express doubts.

Ramon dos Santos, a leader of the Karipuna people, noted “70% of indigenous territory is water”, influenced by “tidal dynamics”, and that for this reason “he doesn’t know what could happen if there is an accident”. Maxwara Nunes, school director of the Galibi-Marworno people, spoke of the Cassiporé river, near the coastal area which has a “number of streams interconnected” to the Uaçá land. Chief Damasceno Fortes Karipuna said “any slick would indeed reach indigenous lands by means of the tide.”

Ramon suggested hiring indigenous environmental agents to monitor the enterprise’s impact, starting with the flyovers, and the cacique Nasildo Nunes suggested an “indigenous component” in Petrobras, “so the communities are aware of what is happening”. “We wanted to include some indigenous representatives within the Petrobras structure, in order to monitor and pass the information on to us in a clearer way, but they said it’s difficult, they didn’t really agree, maybe the sticking point is on the technical side. We explained there are indigenous people who are trained in a number of areas,” said Edmilson.

In the face of the questions, Daniele, the manager of the state-owned company, asked those present to talk about “positive impacts” Petrobras could bring to the indigenous peoples, and asked for proposals. Priscila, who is also from the company, mentioned a “range of options” in terms of consideration, talked about donating computers and training people, and gave details of the launching of a public notice for socio-environmental projects that includes the region. “One of the caciques said: if I don’t have good information, I may end up saying no to something that is good for me and yes to something that is not,” according to Daniela, from WWF.

One of the strongest demands was made by Priscila Barbosa Karipuna, the Apoianp’s leader. She pointed out there had been “failures right from the start of the dialogue process” and affirmed indigenous people “are not against any enterprise, but want the consultation protocol to be respected”. She said the delay in consultation is putting “pressure” on their leaders – one of the great concerns of Oiapoque’s native peoples is being accused of “holding back development” in the face of the expectations of employment and economic rewards the enterprise could bring to the municipality.

Although Petrobras stressed at the meeting that it currently only has a small team in the city, with 20 people, the company’s activities are often highlighted in the social media of the town hall, which is headed by Breno Almeida, who was elected in 2020 by the Brazilian Labor Renewal Party, which does not have any federal deputies but went as far as engaging in negotiations for Jair Bolsonaro to join the party back in 2021. On March 8, the city government reported on Instagram that the state-owned company had signed an amendment for renovation work at the airport. A day earlier, it gave an account of a talk about the Airport Emergency Plan “in the briefing room of Petrobras’ passenger terminal.”

Petrobras says there is no forecast of any direct job creation in the city, “given the activity is temporary,” but that if production occurs, “it is only natural that other opportunities will arise.” “We are aware of the local population’s expectations. This became clear in the expanded meeting held in Oiapoque in November 2022. At that meeting, we gave a commitment to structure ourselves together in order to promote social improvements by means of technical training,” said the state-run company, adding the public notice for socio-environmental projects allows local institutions and, therefore, local people to take part.

Simulated oil spill accident

While the clashes of interests play out in Oiapoque, the licensing process moves forward. On March 3, at a meeting between the state-run company’s representatives and the new person responsible for the General Coordination of Marine and Coastal Enterprises in Ibama, Itagyba Alvarenga Neto, it was agreed the simulated oil spill accident would be held this month, in principle on March 20. It was agreed the date would be confirmed at a later meeting.

Pescadores em Calçoene, a 200 quilômetros de Oiapoque, no litoral do estado do Amapá: modo de vida no extremo norte do Brasil está ameaçado pela exploração de petróleo na foz do Amazonas. Foto: Victor Moriyama/Greenpeace

The Pre-Operational Assessment is expected to take place in the area of Block 59, and six Petrobras vessels will take part – the company added an additional vessel to the five that were available a month ago, and it has already undergone inspection by Ibama. The so-called Individual Emergency Plan, which will be tested in the simulation, had to be reinforced because the enterprise’s shipping base is in Belém, 43 hours by sea from the well site. Given the mangrove coastline does not allow deep-draught vessels in Oiapoque, it is necessary for ships to rotate to areas close to the drilling site, in order to be able to take action in cases of emergency.

According to the minutes from the meeting, Itagyba told Daniele Lomba, the Petrobras manager, that block 59’s licensing is a priority and Petrobras has been meeting all of the environmental agency’s demands. However, Ibama’s coordinator, noted the process “is being overseen by a lot of institutions and entities and, therefore, needs to be very well organized in such a way as to support higher authorities in the decision making about licensing. Daniele said “there are a lot of people involved and mobilized to execute” the Pre-Operational Assessment, with the entire structure already in place.

In its latest technical opinions, Ibama pre-approved the Fauna Rehabilitation and Depollution Center, set up in Belém for the treatment of birds that might be affected by an oil slick and has already been licensed, in mid-February, by the State of Pará’s Environment Department. The institute requested a series of items of information in relation to the Fauna Protection Plan, considering it to be “insufficient and inadequate” in certain aspects, when considering the travel time between Block 59 and the locations where the animals would be treated. However, in an internal dispatch, it admitted “it may not be possible for the company to fully comply with the level of detail requested, particularly because it deals with a topic such as an emergency response strategy, which is prone to a number of operational contingencies in the river basin of the mouth of the Amazon, which is an area that “exhibits immense logistical difficulties”.

In early February, in response to a question from SUMAÚMA, the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change and Ibama suggested that for an informed decision regarding the licensing, it would be necessary to carry out a more comprehensive assessment of the compatibility of the Mouth of the Amazon region with oil activity. Marina Silva’s ministry and the institute cited a technical opinion, of January 31, which states that “the absence of a strategic environmental assessment, such as the SEA [Sedimentary Area Environmental Assessment], and other environmental management instruments, significantly hampers making a decision in relation to the activity’s environmental feasibility, in an area of conspicuous socio-environmental sensitivity and which is a new frontier for the petroleum industry.

Spell check (Portuguese): Elvira Gago

Translation into Spanish: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Mark Murray

Photography editing: Marcelo Aguilar, Mariana Greif and Pablo Albarenga

BIRDS ON THE BEACH OF GOIABAL, ON THE COAST OF AMAPÁ, IN THE EXTREME NORTH OF BRAZIL. THE INDIGENOUS AND TRADITIONAL COMMUNITIES AND THE ECOSYSTEM OF THE REGION ARE ALREADY FEELING THE DISTURBANCES OF POSSIBLE OIL EXPLORATION IN THE MOUTH OF THE AMAZON. PHOTO: VICTOR MORIYAMA/GREENPEACE