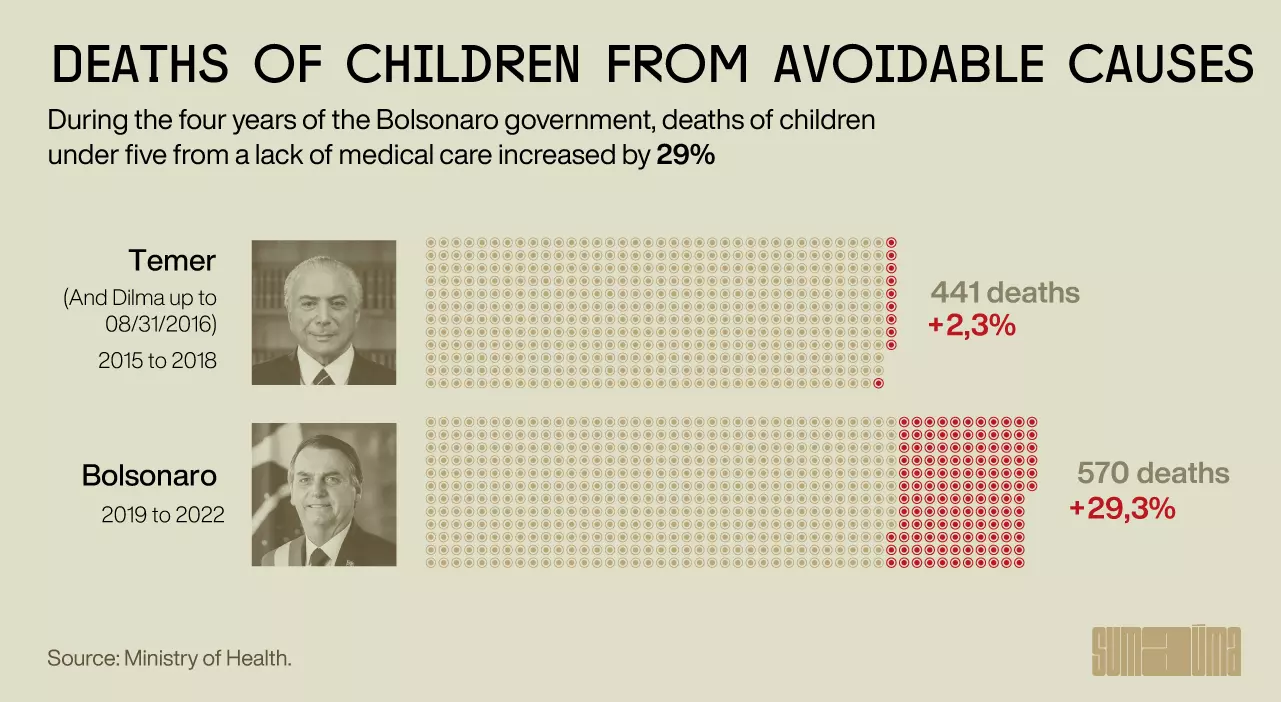

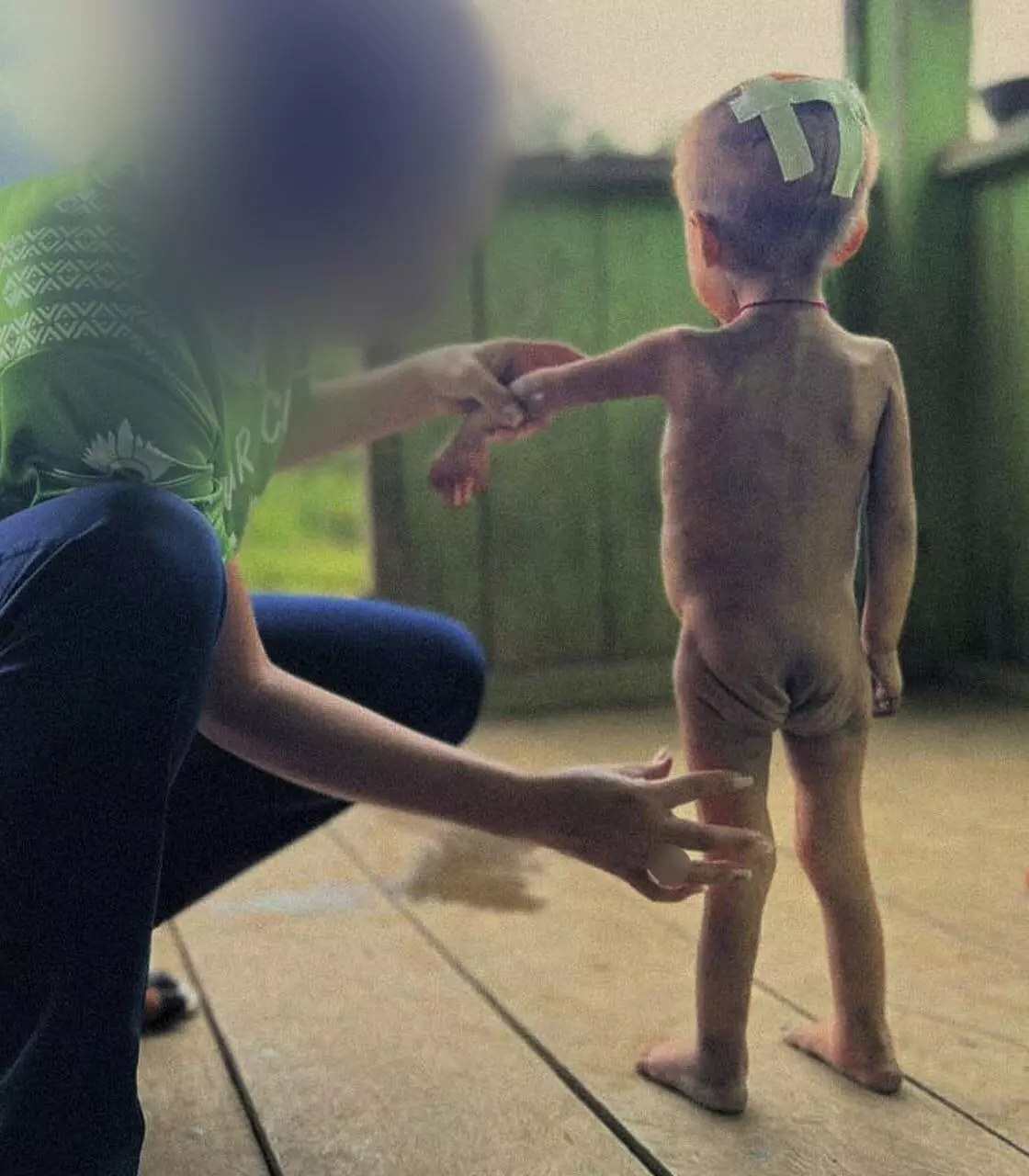

The Yanomami child had already lived 1095 days, but weighed the same as a newborn baby. Three years old and just 3.6 kilos. This figure conveys what a series of recent photos received by SUMAÚMA show: the bodies of children and old people, whose skin just about covers their bones and who look so fragile that they barely seem able to stand up straight. Ribs that seem to pierce the tiny bodies contrast with the huge bellies that are full of worms. The figures obtained by SUMAÚMA indicate that In the 4 years of Jair Bolsonaro’s far-right administration, 570 young Yanomami children died in Yanomami territory, in what statistics refer to as “preventable deaths”. What this means is that 570 children could be playing, right now, if there had been proper health care or preventive actions. There weren’t. The official number is already 29% higher than in the previous four years of Dilma Rousseff’s government and, after her impeachment, Michel Temer’s administration. Since large parts of the territory suffered a statistical blackout during the aforesaid period, the real figure may be even more terrifying. This is the legacy in Brazil of Bolsonaro.

The images in this report were produced by indigenous people and health professionals who managed to get past the barrier of criminal miners and reach the Yanomami Indigenous Land in recent months. In order to be able to publish them, SUMAÚMA asked the indigenous leaders for their permission. Some of the most shocking images were not released because they were offensive to the ethnic group’s culture or because they put the life of the person who took the photos at risk. The publication of the images is a difficult issue for the Yanomami. The leaders who agreed to release the images only did so because they are desperate. In one of the images, it was the cacique himself who asked for a photo to be taken in order that the world could see it. This attitude, which is so rare for a Yanomami, gives an idea of the level of dread of seeing children and elders dropping day after day.

“We are not even able to count the bodies,” said one of the eight people heard by the reporters in recent days. All of them describe a catastrophic scenario within Brazil’s largest demarcated indigenous land. In the territory between the states of Roraima and Amazonas, where almost 30,000 Indians live, hunger has spread in a land that is full of food. Already weakened, old people and children fall victim to diseases that are treatable, but where only too often the treatment fails to arrive. Neglect becomes a death sentence.

On top of this, the dismantling of indigenous health care during the four years of Bolsonaro’s government has led a number of villages to health collapse. With little access to health care and a shortage of medicines, children and old people are dying of malnutrition or treatable diseases such as worms, pneumonia, and diarrhea. “There’s a lot of miners, a lot of malaria. They get malaria and then they can’t work in the fields,” says Mateus Sanöma.

His people, a Yanomami ethnic group, live in the region of Auaris, on the border between Brazil and Venezuela, where illegal mining is openly practiced on both sides of the border. Food insecurity has always been a critical issue in the region. Located in the highlands of the territory, there is less food supply. With the illegal mining and the rapid spread of malaria, what used to be a problem has now developed into total chaos. Many of the Yanomani men migrate to mining sites across the border in Venezuela, leaving the women alone to care for the children, take care of their fields, fish, and hunt in a region where food is scarce, throwing the entire way of life out of whack. “In my community, everyone is dying of hunger. So far 30 Sanöma have died and more will die. They are dying fast. I don’t want them all to die. We need help so that my entire people don’t die,” the Sanöma leader despairs.

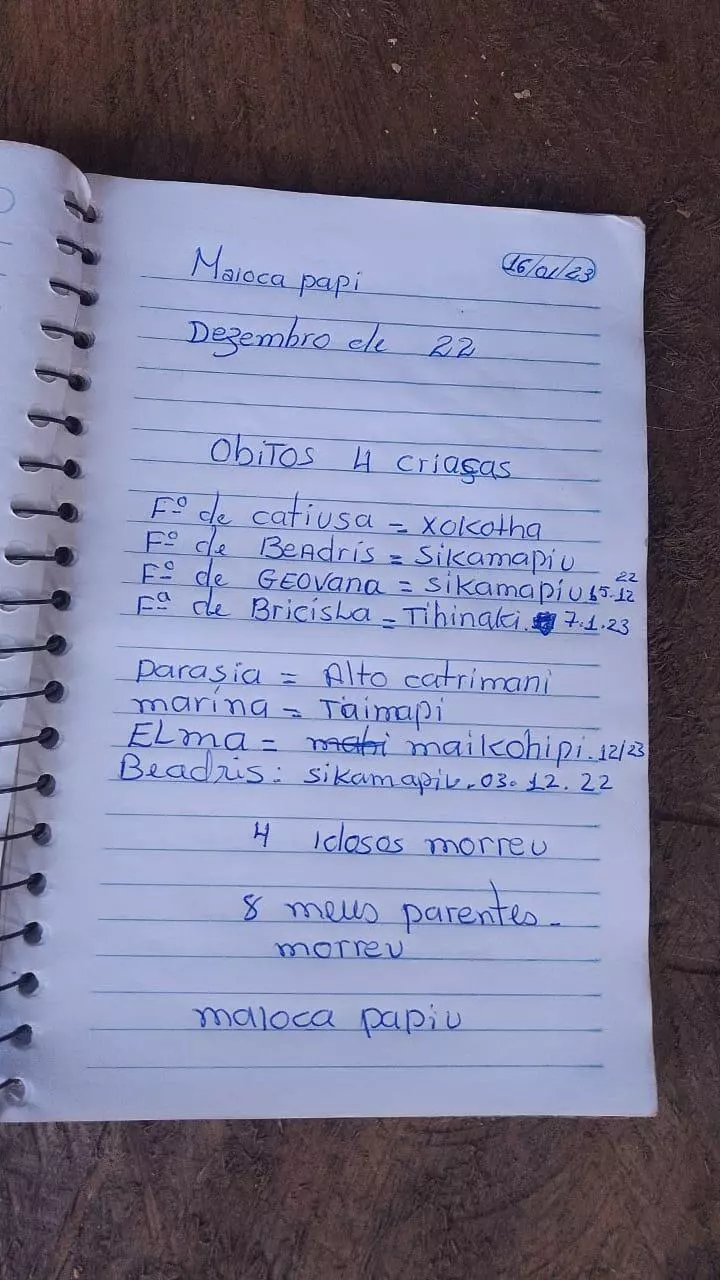

In the last two years (2021 and 2022), the Auaris region, where 896 families live, had 2,868 cases of malaria. Data obtained by SUMAÚMA indicates that just in 2022, 6 children under the age of 1 died from causes that would be easily preventable if there were access to health services or medicines. In the region, 6 out of 10 children exhibit nutritional deficits, in other words, are underweight for their age, and most of them are already suffering from severe malnutrition. In Maloca Paapiu, which is another region in the Yanomami territory, the same thing is found: 6 out of 10 children are malnourished. It is from there that we received a list of the deaths that occurred between December and the first days of January: 4 children, Catiusa’s, Beadriz’s, Geovana’s and Briscila’s daughters. Along with four other old people. “Eight [of] my relatives died,” the note reads.

“In the week I was there 3 children died, all from pneumonia. Another one was saved, she was taken [to Boa Vista hospital],” says a professional who was in the Xitei region in December to work for the Census. The figures show that in 2022 13 children from the Xitei region under the age of 5 years died from causes that were treatable: 6 of them from pneumonia, 4 from diarrhea, and 2 from malnutrition.

Official statistics should, but do not fully reflect the scale of the humanitarian tragedy experienced by the ethnic group and described by those who live and work in the territory. According to them the real figures are much higher. Many of the deaths that occur in the villages are not even reported to the medical services. In some of the regions that are most affected by the illegal mining, the health teams have been kicked out and cannot even provide care or count the dead. This leads to cases like that of the Homoxi region, where the health center was taken over by criminals, became a fuel depot, and was burned down by miners in December in retaliation for a Federal Police operation to combat the illegal activity. According to the statistics, no children there are malnourished, which does not reflect the true situation. Since there is no monitoring by health teams, there are no figures either. The children who are hungry, falling sick and often dying were also deleted from the system. Statistical deletion is yet another way of encouraging death.

The helicopter used for medevacking people who are sick in remote areas, which larger aircraft cannot reach, was broken for 10 days between December 24 and January 4. Damaged, it took a long time for it to be replaced. During this period, according to the leaders and professionals interviewed, at least 8 people died – 4 in the Surucucu region and 4 among the Sanöma. However, according to the official statistics, only three children are listed as having died between December 24 and 27. Therefore, five are a statistical blackout.

“In Koraimatiu I just received the news that the helicopter helped, but 4 bodies were left,” warned the message from a health professional that reached us in early January, just after the helicopter returned. He described a scenario that was like something out of a war. The community could not even hold the cremation ceremony for the dead, as there were not enough healthy people. “In Porapë, four people died. I just found out that another child has died. The tuxaua [leadership] died too. We need to reach those who are the farthest from the airstrips,” continues the same source in the message in which he asked for help.

On January 6 SUMAÚMA’s reporters asked the Ministry of Health about the situation in the territory. The response with the official figures was only sent on January 18. Last week, Lula’s government, which has inherited years of deliberate neglect on the part of Jair Bolsonaro’s government, hurriedly set up a task force, with specialists from Brasilia and Boa Vista, to assess the situation. Since the start of this week, they have been visiting the most affected regions in order to set up an action plan and try and avoid any further deaths. A situation room, like the one that is set up in times of war – or during health crises such as the Covid-19 one – will operate by providing advice to the health teams. They will also have to make an assessment as to what extent the figures in the Ministry of Health’s system corresponds to reality. However, the task of rebuilding the health system will not be an easy one. In those territories where crime has operated freely in recent years, the structures have been destroyed.

“The only food that the health centers have to give to the sick Yanomami is rice and that’s all, nothing nutritious,” said another professional, who was in the territory a number of times over the past year. “There was no medicine, not even pain-killers, nothing was arriving. You could see worms coming out of the children’s mouths. We will have to start from scratch, all over again. The Yanomami were left to their own devices.

A Census worker, who worked in the territory for decades and went back last year, said that the “situation is heartbreaking.” “Health professionals work in subhuman conditions. Health posts with leaks, without any water or electricity. Sometimes the professionals have to walk more than 300 meters just to fetch water in a bucket. There is a shortage of even basic medicines,” he says. “The people are way too hungry and everyone is extremely thin. Even the work of the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) was difficult. When we had to stay overnight, at dinnertime, the team had brought food, but the whole village which was starving to death, hung around the team, which divided the little food that it had brought. We can’t wait any longer.”

TRANSLATED BY MARK MURRAY