Patri’s autobiographical writings

by Marcela Ulhoa*

Patri is her fictitious name, a choice meant to protect her identity in a land of violence. She first wrote some of the memories shared here in a small blue spiral notebook; the rest were gathered during a conversation we had in early March 2023 in Boa Vista, capital of the state of Roraima. Patri has been drawing and writing regularly about her experiences and journeys ever since leaving Venezuela for Brazil in 2017. Her collection of notebooks contains details of her childhood, her relationships with both her adoptive and biological mothers and with boyfriends, and her journey as a migrant, mother, prostitute, and woman in the mining encampments. She dreams of publishing a book someday, stitching together the pieces of her life. For Patri, her stories offer an opportunity to talk to other women like herself. “I didn’t know anything. They said you could make quick money in the camps. If I had read a story like mine, I would have thought many times over before coming, or I would have come better prepared.”

More than an account of her personal experiences, Patri’s autobiographical writings serve as a historical and social profile—the profile of a woman who as a teenager was abused by her stepfather, ran away from home at the age of fifteen, and decided to leave her country at the age of twenty-seven. When she arrived in Brazil, she entered the world of sex work, got pregnant by one of her clients, and tried to live a love story but ended up alone with her son. Since Patri was used to running risks and suffering all types of violence, life in the mining camps sounded like a good opportunity for her. “I took my chances twice [in the mining camps], and for the same reason: hoping I’d have a little luck. There’s danger all over, and in the city, I wouldn’t get any gold. But a lot of things happened that changed the game. Nothing turned out like I’d planned.”

One of the five camps where Patri spent time in the illegal mining region, where she went to take her chances. Each cabin belonged to an owner of gold mining equipment. Photo: personal archives/Patri

The regions of Homoxi and Xitei were her destinations both times she left her four-year-old son in the care of a neighbor in Boa Vista to venture out in search of the coveted “Eldorado.” In Venezuela, there was in fact a well-known mining field called Eldorado, where many women worked as prostitutes servicing miners. But in Brazil, the illegal mines were not at all what Patri had imagined. In Brazil, she lived in mining camps twice, first in 2021 and then in 2022. According to the report “Yanomami sob Ataque” [Yanomami under attack], compiled by the Hutukara Yanomami Association and Wanasseduume Ye’kwana Association in 2022, the Xitei region saw the highest relative increase in mining-related deforestation inside of Yanomami Territory in 2021—a whopping one thousand percent.

During Patri’s longer stay in the Yanomami Indigenous Territory—five months in mining camps—she filled her pockets with some twenty-five grams of gold, worth roughly $1,000. She spent time in a total of five mining camps in Yanomami Territory. In each, there was a different nightclub, a different “owner,” and a new experience “in the life.” Set against the complex backdrop of Brazil’s criminal mining industry, Patri’s account also gives voice to the stories of many other women who endure life on the edges, balancing the thin line between money and brutality.

(Marcela Ulhoa. As a journalist with a master’s degree in literature from the Universidade Federal de Roraima, Marcela edited the raw material of Patri’s stories. She has worked with migrants, refugees, and Indigenous people in the state of Roraima and drawn research from Patri’s private diaries. Marcela’s first documentary as a director, Aquí en la Frontera [Here on the border], will be released this year.)

Fifteen grams of gold, a clandestine plane, and lots of debt

When I was living with my son’s father, back in 2018, I heard various people talking about the garimpo [illegal mining operations]. I didn’t know what the word really meant, and I got so curious, I asked why he didn’t go, since we were going through a rough money crisis, and I was out of work, just like him, and I was pregnant. “Are you nuts? I’m not going to die at someone’s hands there, much less for gold. Nobody knows if I’d get any or if they’d kill me.” I said, “We always have to go after things with positive thinking, so it all works out. If you trust in God—I always have God at my side, brother—you’ll be a good winner!” But with him, it was ‘no’ to everything, ‘I’d just as soon eat rice with butter, but I won’t go.’

And then I started hearing that women were heading there. I thought, I’ve worked the streets, I’ve been raped, my cousin and I were nearly murdered and buried by four guys in a car, and we weren’t even sleeping right, just to earn $80, $100. We’d already faced danger, so [I thought] why don’t I go there? I’ll take my chances, I’ll risk it! And I made up my mind. When I decided to go, I was separated from my son’s father and was living in a neighborhood on the outskirts of Boa Vista, without a job. It was June 2021.

I talked to a girlfriend who knew what it was like in the garimpo, and she mentioned that an acquaintance of hers was there, and that her boss lady needed a woman to work in the nightclub. The one-way trip there would cost fifteen grams of gold [roughly $600].

I spoke to my neighbor; we were good friends back then. “I’m going to the mines tomorrow and don’t have anyone to leave my son with.” She said, “Do you suppose my husband could go too?” She was also going through a really bad economic crisis. We got the phone number of the lady who owned the nightclub and arranged for her husband to go. It happened fast, just like that.

Patri lived in mining camps within Yanomami Indigenous Territory, near Indigenous communities in the regions of Homoxi and Xitei. Photo: Daniel Tancredi/SUMAÚMA

They called the next day: “Look, here’s the number of the guy who owns the plane. He’ll go to your house, weigh your things, weigh you, the guy, his things, and at five in the morning, he’ll pick you up and take you to the ranch [where the airstrip was]. Just wait for the plane to get there so you can go to the garimpo.” It rained hard that day. Then they called before ten or eleven that night. “If it keeps raining, it won’t be possible to travel today, but tomorrow we’ll definitely find a ranch you can leave from, because your ticket has been paid for. The ticket will cost fifteen grams of gold, and when you get there, you figure it out with the owner lady.”

They explained to me that there were three types of airplanes: one with a maximum capacity of three hundred kilos [660 lb.], another of five hundred kilos [1,100 lb.], and the “shark,” which can carry over a thousand kilos [2,200 lb.]. I was really thin back then; I remember I weighed fifty-two kilos [115 lb.], something like that. I went in the 500-kilo plane, along with merchandise for the nightclub owner—food, drinks, and bullets.

We weren’t able to travel that day, just the next. “Get in. We’re going to take you far away from here, to a ranch, because the police can’t get there.” I don’t know exactly where it was, or who owned the place; I just know it was really far away. It took us about two or three hours to get there, and fifteen minutes by car to drive from the entrance gate to the shed where the planes were. I saw nothing but forest around us. There were no buildings, no houses. It was out in the middle of nowhere.

The shed had a high ceiling, well built, lots of tools. Two guys—I think they were mechanics—were seeing to the plane before we left. When we finished arranging the things inside the plane, the pilot and I got ready to get in and leave. I took a few pictures on my cell phone and made some videos. I was nervous, not because I was in the air, in the plane, but because I really had no idea where I was going, what the place would be like, or how my arrival would go. What kept me calm was that my girlfriend’s friend would be there too—even though my head was spinning.

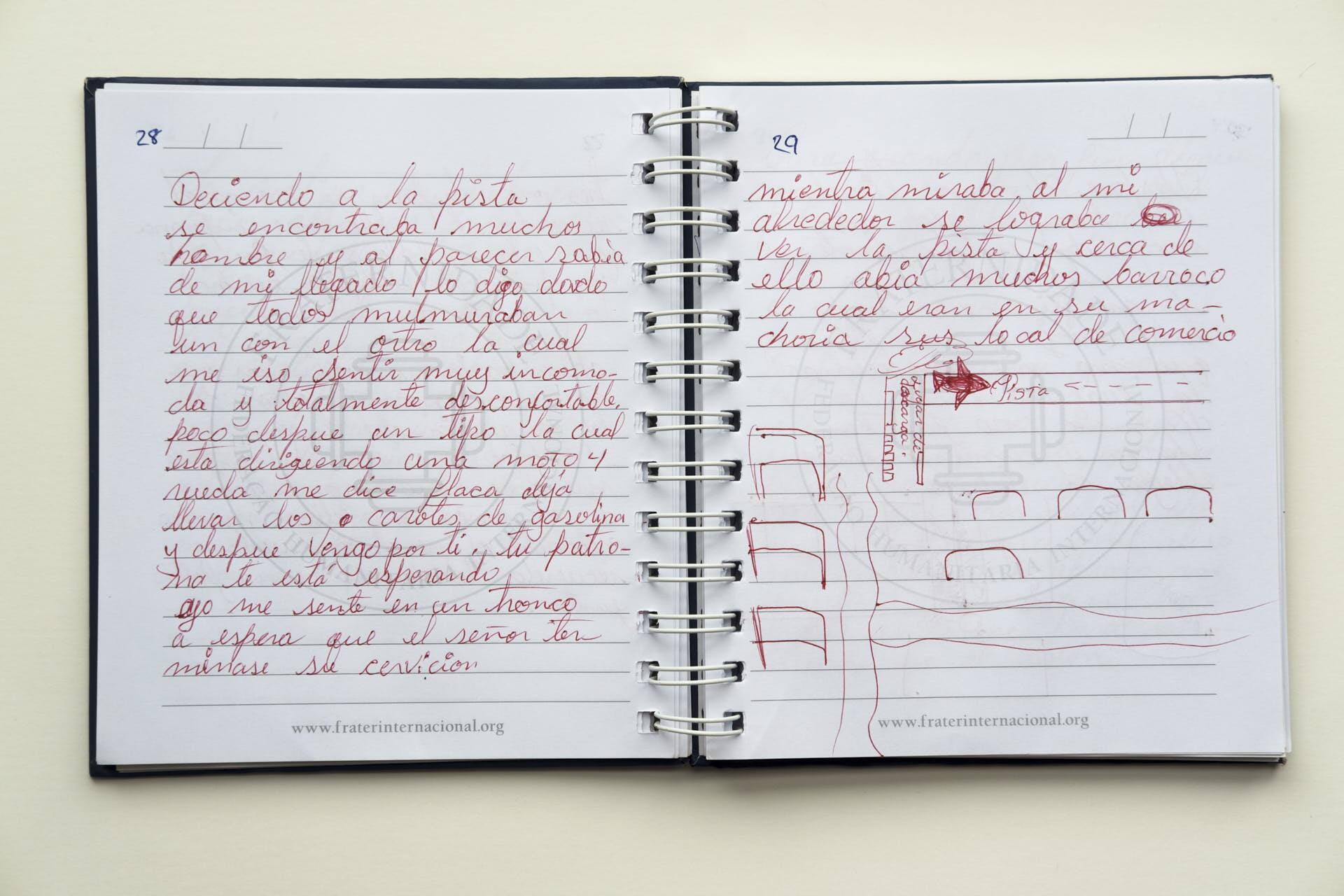

Patri’s journal, showing an excerpt where she talks about her arrival at an illegal mining site by plane. She offers details about the airstrip. Photo: reproduction/Daniel Tancredi/SUMAÚMA

Three hours later, if I remember right, the pilot informed me we were arriving. I remember seeing some of the landscape. There were a bunch of machines and huge pits almost everywhere. The boy who was piloting—he was no more than twenty—told me: “Be very careful.” And he wished me luck. We took our picture together.

Sex with stinking, drunken men—What had I done?

The plane stayed at the mining camp until dawn the next day. The pilot left, and we went to the nightclub. We walked, and I didn’t have boots; I didn’t know what we needed to have there. I was wearing just my black sandals, a pair of torn jeans, and a baggy green blouse. I had a little something around my neck, a silver chain with the letter “Z,” which is the initial of my younger sister’s name. When I finally got there, tired, I went to the boss lady, Bruxa [fictitious name], and my girlfriend’s friend, who said: “If you can, be blind, deaf, and mute, and try to be very patient and calm and don’t talk much.” By telling me this, she was leaving it clear that this wasn’t a place where I could make mistakes, and that it’s you and just you.

When Bruxa came over to me, I thought, “Where’s the boss lady?” Because in the WhatsApp photo, she was younger and stronger. But when she approached me, she really looked like a witch [bruxa]. She was an older woman with a very scruffy physical appearance—thin, tall, lots of badly dyed hair, dry skin, and a face covered in expression lines. She came up and stroked my hair, hugged me, and told me to bathe and fix myself up to go sit in the “lounge.” The lounge was an open area covered only by canvas, with a pole in the middle where women would strip and with big wooden benches where all the hookers sat and argued among themselves about who their clients were.

Feet on the ground: having left life in the mining camps behind, Patri talked about this period of her life in an interview to the journalist Marcela Ulhoa. The mosaic above registers a walk around Boa Vista, capital of Roraima state. Photos: Daniel Tancredi/SUMAÚMA

I didn’t feel any good energy from my boss, no kind of comfort. I was super dead tired, but I suppose it didn’t matter to her. The faster I introduced myself to her clients, the faster she’d get back her grams [of gold].

When I was ready to sit in the lounge, a 70-something gentleman came up and said to the boss: “Is she new?” “Yes, she just arrived, but you’re not going to get her.” She already had a specific client for me. There was [also] a girl who had arrived the day before and hadn’t worked yet. So the guy was paying fifteen grams [$600] for her, to take her back to his shack. I saw that this was a different kind of contract—when you agree to stay longer with a guy in his shack, and you have to wash his clothes, make his food, and can’t have sex with any other client during that time. But when this gentleman saw me, he said, “No, I don’t want her. I want this mira” [in Roraima, Venezuelans are pejoratively called mira]. He called me mira because I was the only Venezuelan. “I’ll pay twenty grams [$800] to take her to my shack for seven days.” But the owner lady didn’t want to let me go.

When you get [to the mining camps], what you have between your legs isn’t yours; it belongs to the owner. You can even say you won’t stay, but your conscience knows that you owe. So she’s sending you, and you have to go. Or at least make her money. If you’re not used to drinking cachaça [Brazilian sugarcane liquor], you’re going to have to make the guy spend money drinking it. The canteen owner sells bullets, and there’s a lot of peões [mine workers; literally, “peons”] with guns, and they run out of bullets because normally, when they get drunk, they shoot in the air. So you go over and say, “Come on, teach me how to fire, how to shoot.” Just to keep them all consuming.

You’re “in the life,” like they say. You’re in the game. You have to learn how to play because you don’t want to lose all the time. If you lose, you’ll leave there broke, nothing in your pockets. When you pay your fifteen grams, from then on you want to stay at the nightclub making money. But everything’s expensive in the camps. Earn some, spend some. For you to feed yourself every week, you have to pay the cook one gram [about $40]. If a nightclub has seven women, they all have to pay the cook one gram of gold every week. This is money for the owner because she’s also the one who manages the cook’s work. It’s the nightclub owner who manages the flights that bring in the merchandise, because everything comes from outside. To get internet access, you have to pay as much as sixty grams of gold [$2,430].

Usually your first payments—if you’re clever, because there are clever women—will land in your hands. If you know how to do the job, if you were already used to it, if you were already wise to the field, that gold will reach your hands and you’ll pay the owner later. But if you’re a rookie, like me, just like the other girl who arrived before me, it’ll fall into the owner’s hands. And you won’t even know how much the client paid. Me, for example, I had sex with four guys, and it was practically free. Nothing ever got to me, and she said nothing ever got to her, but they swore to it and fought with her, saying they’d actually paid four grams a night for me [$160] .

The first two, three days were a little challenging for me because working the camps is actually worse than working the streets. My expectations bottomed out. Because all these peões, they don’t shower properly, obviously. Because hygiene there is a real disaster. You have to ask to go down to the river, take a bath in the grotas [holes caved out in a riverbank by the water]. You don’t have any privacy like taking a bath in a real bathroom, pooping in a real bathroom. There are a lot of things you have to adapt to. And the climate was bad for me; I’m allergic to those big mosquitoes, and I’ve got that fear of the dark. And there were a lot of people drinking cachaça, all day long.

The nightclub is a structure built out of tree trunks. We contributed to the destruction of the forest. There are different kinds of structures, with big heavy canvas tied with rope, real strong, real taut, to make a kind of roof. And rooms, which we call “fuscons” in the camps. Our fuscon is literally the place where we work. I don’t know if that’s a word from Portuguese; I heard it for the first time in the camps and was never able to find out what it means. I think the miners adapted this language from the Indians. It’s the same as when we say xapona, we know right away that it’s an Indian house.

Abandoned mining camp along the Uraricoera River in Roraima state. The sign left hanging in this otherwise deserted spot bears witness to the women who once lived here: “Just Nails: Embellishments. Classic. Gel. Acrylic. Henna eyebrows.” Photo: Guilherme Gnipper/FUNAI

The nightclub owner will often supply you with beds, but there are many nightclubs that only supply the fuscon, which is the little room, and you take your hammock. And working in a hammock is awful. A bed is more comfortable for this kind of work. And leaving a hotel room to go to a fuscon like this, where there’s nothing but mosquitoes, the noise of mosquitoes, all kinds of bugs under your feet, and have sex in a hammock with someone all dirty, all stinky, all drunk on cachaça, not knowing if he’s going to hit you and with nobody to help you…it’s all crazy. That’s when it hit me: Shit, what have I done? I realized that some decisions you make in your life will often have huge consequences. You regret it so much you can’t stand it.

There’s a moment in the camps when you go crazy. You get that adrenaline rush; you’re always afraid, feeling persecuted, thinking that so-and-so gave you a dirty look. Your attitudes start changing in the camps, simply from the fact that you know you have to get respect. Because otherwise, mano, you’re not worth anything. If you’re weak, they’ll abuse you so much. The guys force you to do anything they want.

Most women who own nightclubs have a real distinct history in the camps—distinct in the sense that their story in the camps before they were owners, before they made money or earned respect in the camps, is real well known, because everything is sort of a territory. When I got to the camps, I was afraid of everything, even of talking back to someone or turning down a proposal. Then I realized that there, in the middle of this trafficking, people mark out their power territory. Because you can’t call this anything else—this is trafficking. There’s no other word I can use to describe this situation of drugs, guns, bullets, weapons, gold, gasoline, among other things—many others—that I began to realize in just a few days.

For example, the owner of the first nightclub I worked at—she came with quite a history. When she got real drunk, she’d start spilling the story of her personal life. She’d been raped and sold to men in the camps. I always heard her talking about how hard she worked to raise her two children and get what she had at that point. And she was like that, very arrogant, very forceful in her own way. But sometimes I felt sorry for her because when she got really drunk, she’d talk about how she had once killed someone, because she was raped and there was no other way; she had to kill him so she could escape the camp. And she basically became the person she was because of her situation in life. So I felt sorry for her and developed a friendship with her, I don’t know how. I don’t know if it was because I felt a little bit like she complemented me, with her experiences.

Lose money with transfer fees or take my chances?

Beating out the carpets is what the men who work the equipment do. Once a week they clean the equipment, removing what they call the carpets where the gold is. They clean them, put that chemical on them—what do you call it? Mercury. And they do that processing to make gold. Every weekend, or before the weekend, Friday, or Saturday into Sunday, they beat out the carpets. That’s when more gold comes in, when the canteens, the nightclubs, the pool tables, betting—even the Indians get real drunk.

When they beat out the carpets, it’s really good. A lot of times, there are hookers who are tight with a particular client, and because you’re tight with just one client, the other peões no longer see you as a hooker but as this miner’s woman. But if you aren’t tight with anyone, then you might turn four or five tricks a night [when they beat out the carpets].

Almost every weekend, there is a party at the nightclub—bingo, booze, loud music, striptease. The place is usually crowded and draws people from other camps. Photo: personal archives /Patri

An illegal mining site seen from a helicopter (left); weighing gold received in payment for a standard, one-hour sexual encounter. Photos: personal archives/Patri

Outside, gold goes for three hundred Brazilian reals [$60] a gram. But in the camps, since there’s lots of gold, it’s 180 Brazilian reals [$36]. And you’re charged a fee for every bank transfer, which ranges from fifty to seventy Brazilian reals [$10-$14]. So you literally lose money when you sell your gold inside the camps. Now here’s another option: you have ten grams of gold and want to send it out. You can, but you’re taking your chances. What happens? [You give your gold to someone] and later this person might come back with a story: “The police got me, they took the gold.” The gold got there “chueco”—that means incomplete. Instead of ten grams, five grams got there. So for me it was better at least to send out 180 Brazilian reals than three hundred Brazilian reals [that might never get there].

The day an old guy put a knife to my throat

The second time I went to the mining camps, in 2022, I had a very rough time once. One day a client came along who worked for the owner of the nightclub—who didn’t just make money from the nightclub but also from [goldmining] equipment. Bueno, this client drank so much that he told me he was going to the bathroom, but when I went to my fuscon, I found the old drunk sleeping in my bed. I reported this to my boss, who was with his lover in his quarters. He told me, “Sleep in another one, since your friends have left”—in other words, fueran pal coño [they went who the fuck knows where]. I went and laid down next door.

Somebody arrived about two or three in the morning. I heard footsteps and someone going into my fuscon and calling me. I answered, “I’m not there, I’m next door.” The fellow comes in and tells me that he’d come a long way to make me a proposal: “I’ve got three grams [$120] and 250 Brazilian reals [$50] in cash. I’ll pay you the other gram [$40] later.”

During a meeting to talk about her story, after having left the mining camps, Patri takes a dip in the waters of a Roraima river. The location cannot be identified for reasons of security. Photo: Daniel Tancredi/SUMAÚMA

The fellow’s feet smelled real nasty, not to mention my patience was wearing thin because he wanted to take his condom off. I suggested that if he insisted [on removing the condom], he could take his money and leave. Because I take care of myself when I work; I don’t go along with that. So he finally saw he wasn’t going to get anything and said, “OK, I won’t bother you anymore, because anyway [with a condom], I’m never going to get off.”

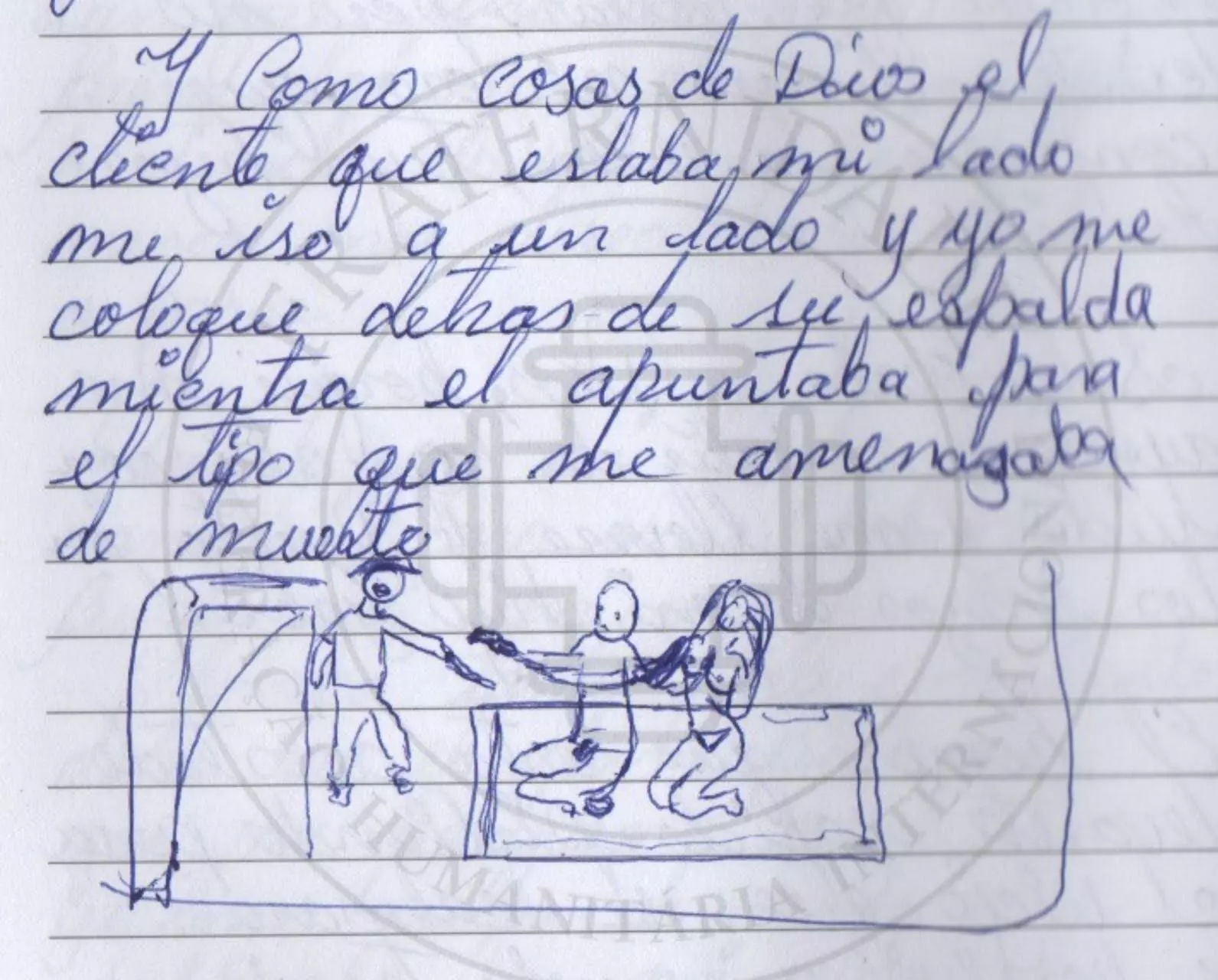

The old man sleeping next door in my fuscon woke up, and I felt something palpate inside me, kind of like a warning. He pulled out his machete and ripped the fuscon: “Come on, wake up, you bitch! Where are you?” I opened the other side of the fuscon and ran out. He chased after me, cursing me, saying, “Damn Venezuelan, I’m going to kill you. What do you think I am? A sucker? I’m a man, respect me, damn you. I’m going to kill you now!”

He pushed me up with his knife; he put it right against my throat and said, “Get up, get up, bitch! I’m talking to you!” The moment I got up, he pointed the machete straight at me, to cut me, and said, “Go send a message to your son and say goodbye to him, because you’re going to die today.” The second the man said that, I shivered cold all over. I cried and begged for mercy, “For the love of Christ, please don’t do anything to me. I didn’t make any arrangements with you.” At one point I was in front but then, I don’t know how, in a matter of seconds, I got turned around and was behind the guy I’d been sleeping with. And this guy had a revolver under the mattress, and he said, “Hey, flaco [dude], put that machete down and leave the girl alone because you’re in the wrong. The girl’s not with you; she’s not your company for tonight.”

I got up and rushed to the place where my bosses were sleeping—because they were a couple—and I explained [what was happening]. They just laughed; they thought it was funny. So you see the reality there. You’re not protected by anyone.

I remember real well what the client said: “I’ll give you the six grams [$245], but you’ve got to leave this nightclub today, because if you don’t, you’re going to die.” That’s what the guy told me, an older guy with experience in the mines. “You’re going to die. Get out.” You think I slept that night?

I woke up at six a.m. and had a little breakfast, not feeling like it at all, feeling out of it, disoriented. And the boss man saw me and said jokingly, “And so mira, how’d it go?” I looked at him, and you know what I said? “Fuck you and your fucking nightclub! I pray to God you don’t get another gram off us, off all the women here.” Then the guy said, “If you feel like leaving, you can, but you have to pay me nineteen grams [$770] of gold now.” And I replied, “What do you mean, nineteen grams? We agreed to thirteen grams [$525] for me to come here.” And he said, “No, it’s nineteen grams; if you want, you can leave; if not, you can’t.” I remember quite clearly that I had twenty-one grams [$850] of gold, and this was before the beginning of the month. I said I’d pay the nineteen grams because I couldn’t stand the sight of him. I said a bunch of things to him. We cursed each other out, and he said we Venezuelans were ungrateful.

That day I went down to the grota. I cried a lot, took a bath—a bath in água bendita [holy water]. I remember this day was what hit me hardest. I thought, “I’m here, alive, taking in nature’s water, feeling the water touch me. I’m here, dazed, but here.” The grota is a hole with a bridge over it, and you can wash clothes there, drink water, take a bath, because it’s running water. And I laid down there and stayed a good long while. I didn’t want to go to the nightclub—some man next to you, calling you “sexy.” I didn’t want to be there.

I finished taking my bath, cleaned myself up, washed my clothes, and went to hang up my clothes, wait for lunch, and go eat. And the other peões said, “What’s up, mira? Come on, I’ll take you to another camp.” I said, “How?” And they said, “We’ll take you. There’s some Indians who take women [to a nearby mining camp].” I asked, “Where is it?” And they said, “Far away from here. You’ve got to walk two hours, give or take, through the woods. It has to be a reliable Indian.”

I remember I took my clothes, folded them, packed my bags, paid the nineteen grams, said goodbye to the cook—she liked me a lot—and said goodbye to the fellows who worked for the man, the owner of the nightclub, the guy who had mining equipment. Besides the nightclub, he owned equipment, he had a canteen, he had a lot of money. And off I went.

I never had an Indian client

After an hour [of walking], I rested in the middle of the woods with two Indians and two Brazilians who were headed in the same direction. The Indians travel from one camp to the other, and they never disrespected me. On the other hand, we kept teasing them, saying, “Oh, do you like women, do you like sucking?” And they’d say, “Not me, me married, my wife.”

I never had an Indian client. If I had been with an Indian, I would have been kicked out on the spot. Or at least I would have been rejected by all the peões. I would have been forced to leave the camp because I wouldn’t have any clientele. In most people’s heads, Indians aren’t clean; they don’t take care of themselves. And they’re practically innocent; it would be like taking advantage of a whole different situation. If it’s about sex, there are a lot of Brazilian peões who are here for sex, and if it’s about gold, those same Brazilian men can offer you gold. But an Indian? I don’t know. That’s how we think about them there.

I never saw an Indian woman prostituting herself, or being exploited, but I’ve heard stories told by the peões. One day a guy was sitting with me, and he said, looking at a twelve-year-old child, “Holy Mary, that chinoquinha [diminutive of chinoca, slang for an Indigenous girl; also used for a prostitute]! She’s beautiful! Those pretty little boobs. If her pussy is clean, I’ll have her.” That way of thinking irritated me; I stood up and told him a thing or two.

More than once, I heard them talking among themselves about having had sex with chinocas who’d been sold to them. In that camp, the Indigenous women were already drinking [cachaça]. They’d sit with the clients, fight over a man with Brazilian women.

Patri records a stretch of a two-hour walk with a girlfriend through forest and mines. That day, they went to meet the sister of Patri’s fellow hiker, who worked in the kitchen at another camp. Photo: personal archives/Patri

Run, the Indians are going to kill us!

It had been two weeks since I’d arrived at a new nightclub, owned by Pequena [fictitious name], and all of a sudden there was a big problem for all the women who worked as hookers. I remember I got up to take a bath, as usual. We’d see Indians by the river all the time, so I didn’t think much of it. I saw Rubi [fictitious name]. She was carrying a cake to celebrate the birthday of Sorriso [fictitious name], a well-known, very powerful guy, envied by other guys and who paid all the women well.

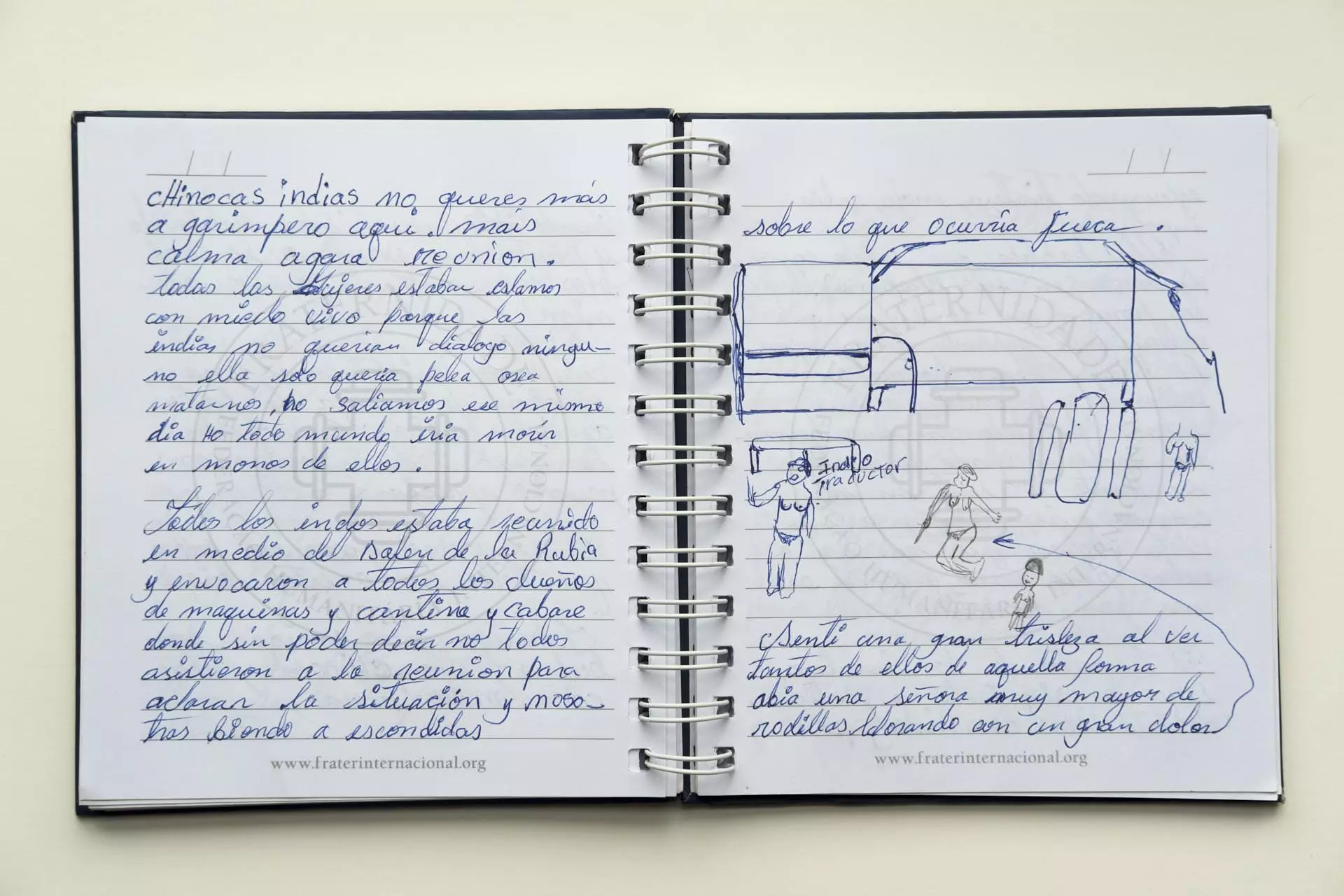

A few minutes later, she came running by, a terrified look on her face, saying: “Indian women, Indian women, they’re coming to kill us! Run, run!” I took off like a rocket, screaming to wake my friends.

Dulce [fictitious name] was confused, and Branca [fictitious name] was so nervous she wanted to run into the woods. And I thought, no, what’s the point of hiding in the woods, if they’re going to catch us there anyway? They know their mountains like the palm of their hand. “Pequena, Pequena,” we all screamed, scared to death. She woke up, because the Indian women broke through part of her canteen with the tip of an axe, all the time talking away in their language. I didn’t understand a single word.

There were a lot of them, fifty Indigenous women and thirteen girls, all of them with children. They were painted red. Others just had some white paste on their faces, which were the ashes of their dead relatives. This indicated they were in mourning, but even so these women took on a fight with all the miners. There was an older lady down on her knees, crying so sorrowfully, expressing sadness, disgust, anger, impotence. There was an Indian man who spoke perfect Portuguese and their language too, and so he helped translate what the lady was saying.

She said she was tired of seeing the men come back [to their xapona] drunk. Men who should be defending their wives and daughters would come home fighting and hitting their wives, fighting with their Indigenous brothers to the point of killing each other. I felt her tears in my heart. I wanted to hug the old woman and say it was all going to end, but why, if that was a big lie? The Indigenous translator had this to say about his community’s request:

“Miners not sell cachaça to Indians! Indians drink cachaça, Indian crazy in head, Indian kill other brother, Indian treat chinoca badly, chinoca cry hard. Indian peaceful before. Head go crazy, canteen owner’s fault. Little child get sick, dirty water. Canteen owner sell only food to Indian. If Indian discover hooker, canteen man, miner, sell cachaça, Indian come and kill everyone. You all respect Indian women, children, everyone, OK?”

In another excerpt from her journals, Patri tells about the day when Indigenous women arrived furious at the nightclub, demanding that those in the mining camp respect Indigenous communities, prohibit the sale of alcohol to men from their villages, and ban loud music late at night. Photo: reproduction/ Daniel Tancredi/SUMAÚMA

Then the Indian women made us cook for them all. They put us to cooking fish, chicken, meat. And they watched us cook. It was humiliating, y’know? But what were we going to do? You couldn’t say no. And so all the women were off cooking, each one cooking two or three kilos of rice, meat, chicken on the grill. And [the Indigenous women] were all sitting there, with a whole bunch of little children, and the Indigenous men protecting them. It was so much to take! They stayed from seven in the morning until five in the afternoon, an hour before the sun hid itself. They have a really cool culture in this sense. They have a schedule for everything. And they went to sleep in their xapona.

The Indigenous women said they shouldn’t sell cachaça to their husbands, they shouldn’t give liquor to the women and shouldn’t give them weapons. And then the son [of the woman who spoke] said, “No! Weapons, yes!” The other Indigenous man said they had to protect themselves from the enemy, from the other mining site. I realized weapons were important for the men, but the women didn’t like it, because the men would shoot off their guns when they were drunk, and there was much more violence in the community.

All of the women blamed us [women] for their troubles. Angry and shouting, they begged us to let them be in peace. They also asked us to turn down our music after nine p.m. because their xapona was real close by, about eight hundred feet away, and it was hard for them to sleep with the noise, to the sound of Marilia Mendonça, Gusttavo Lima, all kinds of sertanejo [Brazilian country] or funk. Given this whole situation, I realized these women were fighting for their tranquility, for their rights. And then within me, I remembered that the Indian blood of my ancestors runs in my veins.

For a moment, the miners—I believe they felt bad, but in their heads, they still had the same things in mind. At seven that evening, all the women from the nightclubs and the equipment owners met to talk about what had happened. The nightclub was packed with clients. We worked hard that day; work went until four in the morning. Low music, but everybody was there.

For the Indigenous, cachaça and shards of liquor bottles

One day, I was drunk and left my fuscon open. And like all the Indigenous—you can tell this about them, they’re very curious; they’re like children. And maybe they saw my open bag; they saw some things that caught their attention. They took shampoo, they took deodorant, a new sheet, some cremes, those kinds of things that I think they liked. And then a while later, I saw an Indian woman with my sheet, which had belonged to my son. But I don’t think it was her; I think it was her husband who took it, because she had a baby. So I thought to myself, just let it go! But I was kind of like, it was my son’s sheet, when he was a tiny baby. It was a sheet with white and black pandas, and I really loved it. So I asked her, “Who gave you this sheet?” And she looked at me like she didn’t know, like she didn’t hablar my language. And so I said, “Hey, you dirty Indian, yeah, you know! You stole my sheet. It was my son’s, I have a son too.” And she smiled at me.

We joked around with them, the Indian women, y’know. We gave them lots of sweets. They eat a lot of packaged sweets—candy, suckers, cookies. The nightclub and canteen owners also gave the children lots of sweets.

The miners, they’re always taking those cases of 51 [a brand of cachaça] and breaking them up, then throwing [the bottles] in the air and firing at them, so they end up shattered all over. And the Indians usually go around the forest barefoot, that’s their natural habit. Nobody knows that better than them. And one of these indiozitos, four years old, a lot like my son, he cut his toe. Just a little more and he would have lost it.

Something went through my body. He cried with so much feeling. And I went to help the little Indian. I picked him up, sat down in the area where the women dance, the strippers [who earn about $20 at the nightclub, less than the prostitutes], and he was bleeding real heavy. The blood just wouldn’t stop. I grabbed some socks and put them on him. I was going to give him some medicine, but my boss man told me, “You shouldn’t give them any medicine because if anything happens, they’ll come for your head.” They don’t let anyone help them. Leave him be. I don’t know where his mother is.”

Then the boss started asking around, “Where’s this boy’s mother?” So they went to get his grandmother because his mother was sick. I don’t know what illness she had, but she was in her xapona. And he said, “Chinoca, get the little boy. He cut himself!” She picked him up—he looked like a doll in her arms—and took him over to a nearby grota, a real dirty one, because this grota, when I got there, it was very clean but then it got real dirty, because they were working there, exploiting the land. They were destroying it, y’know? A few days later I saw the boy again, and his toe wouldn’t move anymore. I think it hardened up, y’know?

So sad. I felt sorry for them. Because sometimes the conscience of a person who has gone to school, who knows the consequences of their actions, when they get to the mines, they change; they seem like animals. They turn into animals; they lose the essence of their education, empathy, concern. So most miners could care less if they hurt a little baby. The miners give the children cachaça. I’ve seen these situations; I don’t agree with it, but there wasn’t any [alternative]. I didn’t agree, but what could I do? I was alone there. If I couldn’t even take care of myself, protect myself…

There was a group that sold marijuana, hashish, crack, cocaine, and they’d give it to the rookies, the young guys who were just getting to the mines. Some of the young Indigenous also bought drugs with the gold they earned doing odd jobs for the equipment owners. The young fellows were paid one gram of gold a day [$40] to unload merchandise from the plane and take it to the boss’s shack or get wood for building the shacks.

I found out Indians have feelings

You’d go up a hill, pass the equipment, and arrive at their xapona. We weren’t usually very welcome there, because that’s their privacy, but once I went into one of those places.

It was under emergency circumstances because something very serious had happened among them. They were fighting each other, a war among themselves. One guy wanted to kick the other group out because they had stolen something, and it wasn’t the first warning from the leader in their area. The other guy didn’t agree because he thought he had the same rights as the leader. And they went at each other with bamboo sticks, hitting each other over the head. They literally split their heads open. From the más pequeño [very smallest], six years of age, to the oldest. Toditos—it was such a visual war that I saw. They were painted black; others had red paint on their faces.

Months after leaving the mining camps, Patri agreed to be photographed in a moment of connection to the forest. Photo: Daniel Tancredi/SUMAÚMA

That same day, at night, one of them came and asked the canteen lady to call a pilot who could come get a fellow who was dying. And everybody was kind of like, I want to help, but that’s a lot of work, it’ll take a while, better tomorrow. But of course it’s not your family, right? And the guy kept insisting, “Call, call, call over the radio.” I remember I sent a message: “Look, there’s an Indian here. He’s dying and they need to get him out of here, because if they don’t, that’ll be another problem.” When I went into the xapona, there was another Indian, worse off than him, whose back had been broken. They were having a vigil for him. I thought it was a vigil with a casket, like we do. But no. They hung him from a tree in the forest for three or four days. [I thought to myself], que vaina és esa? Una vaina que yo nunca havia visto [What the hell is this?! I’ve never seen this before!] Good God in heaven! Me saque de aquí [Get me out of here]!

I felt all sorts of things; I felt disgusted by the smell. But they were crying for the dead man. And the dead man was there in the forest, in the tree. The next day, I saw the Indian women with ashes on their bodies. And they have to leave the ashes on for a month. That’s their mourning, for a brother, a relative. So I learned something new in my life.

When we got there, everyone was crying, singing, very drunk, singing a very beautiful song. I don’t know what they were saying, what it meant, but it was full of feeling. It’s hard to accept their way of holding vigil for a relative, but that’s their culture. I felt really sad because they were really sad. I saw that it was a human thing, [because] I thought they didn’t have those kinds of feelings. I had thought they were savage, violent brutes. But I discovered they feel pain for one of their loved ones. They suffer for their relatives; they cry, they hold vigils for them; they take care of their children. In their own way, but they do.

Despite the brutality that leaves its mark, I went back

What makes someone want to go back to the mines? The money, the gold. Having a dream and expecting to make money fast. Believing in something that you don’t know if it’s going to work, but you have to try. Nobody opens a door if you don’t knock. It’s not about a life of luxury, because that’s in the city. But it’s ambition. And I think I can put myself in this category, because here in the city, I can fight for it, but I won’t get the same results in a short time. It’s risky, it’s dangerous, yes, but it’s a project, a prospect.

From all my experience, I’d emphasize not the satisfaction of having gold in your pocket, but the brutal way women are treated and that leaves its mark. That’s what I’ve experienced most. I never liked the way I was treated. There is very little respect and minimal consideration. In terms of a woman’s self-esteem, she always feels like a hooker, not like a warrior woman. You have to be very strong. You’ve got to have a lioness inside you if they insult you. Knowing they might kill you, you’ll have to fight.

Spell check (Portuguese): Elvira Gago

Translation into Spanish: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Diane Whitty

Photography editing: Marcelo Aguilar, Mariana Greif and Pablo Albarenga

Page setup: Érica Saboya

The brutal way women were always treated, according to Patri, was what struck her most in her journey through illegal mining camps and in life. Photo: Daniel Tancredi/SUMAÚMA