Years of government neglect of the Yanomami territory have transformed the largest indigenous land in Brazil into a minefield that has started to explode. The price of gold and the absence of law enforcement in the area, which is located on the border with Venezuela, a strategic position for drug trafficking, has attracted members of criminal factions such as the First Capital Command (PCC) to the area. The criminal group’s members, who are refusing to give up their lucrative new business, have been shooting at security agents and indigenous villages. In the last week alone, 14 people were murdered in the territory – including an indigenous man. The conflict could intensify further because the PCC has promised to retaliate for the death of one of its members during a police operation at the end of April.

This week the government announced plans to bolster the public security presence in the area, but the faction, which has its origins in São Paulo’s prisons, has responded with a defiant message that reveals it intends to target federal agents. The message which was obtained by SUMAÚMA and confirmed by sources in the Federal Police and the Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (Ibama), who spoke under the condition of anonymity, makes the threat to the government clear. “Are there any comrades out there who would like to kill or who want to give us support so we can send an answer out in response to the deaths of our comrades”. The text intercepted by the Federal Highway Police intelligence service was sent to members of the faction and was attached to a “note announcing the death of a comrade”.

Sandro Moraes de Carvalho, killed at the age of 29, and his partners used to post pictures taken inside Yanomami land, showing off gold accessories and weapons. Photos: reproduction/social media

The faction member killed was Sandro de Moraes Carvalho, a 29-years-old who was known among PCC members as “president”. He liked to publish photos and videos on social media in which he showed off with large caliber weapons inside the indigenous land. The message calling for his death to be revenged was discovered last week, and the retaliation was aimed at police officers. However, since Ibama and the National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples’ (Funai’s) personnel usually work in conflict areas accompanied by security agents, they are also at risk.

The operation to remove illegal invaders from the indigenous land, which got underway on February 6, has now entered its most delicate phase, according to sources in the government and the control bodies who are monitoring the removal of the intruders. “We have now reached the core of the problem,” said one of them, referring precisely to the illegal gold miners who have links to criminal factions and who remain in the territory and are promising to resist. The government’s estimate is that 80% of the approximately 25,000 illegal miners who were in the indigenous area have already left.

Rodrigo Chagas, a professor at the Federal University of the State of Roraima and a researcher at the Brazilian Public Security Forum, said “this resistance has been expected since November [of last year],” referring to the period when Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who had already been elected, began promising to put an end to illegal mining. “There are miners who are saying that they will just wait for the dust to settle before going back [to the territory]. Indigenous people report that in some places the miners have said they will not leave and continue working at night in order to avoid any surveillance.

Ever since February, when a federal task force began to operate in the territory, men armed with rifles have fought back against the police operation by opening fire. Yanomami villages that oppose the presence of criminals have also been attacked and at least four indigenous people have been murdered this year. On April 29, the health agent Ilson Xiriana, who was 36, was taking part in a funeral ceremony in the Uxiu community when he was gunned down by armed criminals. According to the Hutukara Yanomami Association, the community leaders believe the men who attacked are part of a faction that has set itself up in the region, on account of the type of weapons used. Two other indigenous people were shot, one of whom is still in intensive care in the city of Boa Vista. Soon after, the tension escalated. On May 2, eight illegal gold miners were found dead in the same region and, four days later, another body was found – that of a woman who is believed to have worked at a brothel in one of the illegal mining camps. The police have not yet indicated who the suspects in the killings are, or whether the men who were murdered were connected to the criminal organization.

Open territory for drug-traffickers

The invasion by the miners resulted in an unprecedented humanitarian crisis in the Yanomami territory. In the image, law enforcement agents fly over the area destroyed by illegal mining operations in the region. Photo: Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change

The formation of the so-called ‘narco-mining’ camps and the change in behavior of illegal gold miners is a recent phenomenon that is another legacy of the government of Jair Bolsonaro. In 2019, indigenous people in the Palimiu region began to notice the presence of large caliber weapons such as pistols and rifles among gold miners, according to a report by the Socio-Environmental Institute. Furthermore, the criminals, who travelled by boat in front of the community, began wearing hoods and black clothes. In 2021, the indigenous people of the region threatened to prevent the invaders from passing through their territory, but ended up being attacked by gunfire on 10 different occasions between April and August of that year.

The invasion by the miners resulted in an unprecedented humanitarian crisis in the Yanomami territory and was one of the factors behind the death of at least 570 children under the age of five who were unable to get access to proper medical care because health workers had been expelled by criminals. In order to stem the humanitarian crisis, in January a government health task force was sent into the indigenous area. The following month, a police operation was set up. But up until this point, the government has not been able to regain control of some areas – and one of the reasons is the resistance of the criminals. Agents from Ibama and the Federal Highway Police were shot at in regions such as Waikás and Palimiu, in March and April.

Following the 14 deaths in a single week, a significant number for an area where less than 30,000 indigenous people live, the government has stepped up its operations with more agents of the Federal Police, Federal Highway Police, and Ibama. But SUMAÚMA was told by four sources linked to the removal of the intruders this may not be enough, because of the lack of commitment by the Army and the Air Force. The Armed Forces have the greatest knowledge and infrastructure to monitor the border territory, whose security is strategic to Brazil.

One of the criticisms heard from federal police officers is in relation to what they are referring to as procrastination by part of Army, which is the institution that should be responsible for the logistical part of the operation, such as transporting police officers and inspectors and setting up of structures for camps. “Not a single camp has been set up yet in Homoxi, which is the main hub of aerial logistics for the gold mining,” one source said. It was in the Homoxi region, during Jair Bolsonaro’s administration, that a health center was invaded by criminals and became a fuel depot for the miners. The building was burned down by the illegal gold miners in last December, in retaliation for a rare operation by Federal Police. The 3,485 indigenous people in the area were left without medical assistance.

Agents from the Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (Ibama) destroy an airplane used by illegal mining operations in Yanomami Indigenous Territory, in a combat action carried out in April 2023. Photo: Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change

“There are people connected to the territory saying the army is dragging its feet at this moment [of removing the intruders]. The biggest indication of this Ibama and the Federal Police have been joined in operations by the Federal Highway Police [which is not ideal in a territory where transport is by air and river],” concludes the researcher Chagas.

The Army and Air Force deny accusations their personnel are “slacking,” which have been reported by different sources inside the territory. When contacted for comment, the Ministry of Defense, which is headed by José Múcio Monteiro, a right-wing politician who Jair Bolsonaro has said he is close to, stated that “since a situation of emergency was declared in the Yanomami territory in January, the Armed Forces have been mobilized for humanitarian aid purposes” and that since last Sunday, April 30, “they have been on standby to meet further demands in response to attacks against indigenous people”.

The Air Force argued that “since the end of the air corridors [which allowed aircraft to carry miners out of the region] it has notified and intercepted a number of suspicious aircraft, and assisted the security agencies in the destruction of various aircraft. The Brazilian Air Force declared to SUMAÚMA that it “acts in accordance with the laws and regulations in force, which govern the procedures for intercepting and halting aircraft.”

Aiala Colares, a researcher at Pará State University and the Brazilian Public Security Forum, studies the factions that operate in the country’s northern region and has been investigating what is happening in the indigenous land. “The Armed Forces have always been in favor of illegal gold mining, even before the Bolsonaro government,” he said. He pointed out that together the two activities (drug trafficking and illegal gold mining) generate enough money to buy machinery, ammunition, large caliber weapons and to corrupt civil servants.

The State of Roraima is historically linked to mining. So much so that the state capital, Boa Vista, has a monument to gold miners in front of the Legislative Assembly and the seat of the State Government. But there is yet another important factor that needs to be taken into account. Relations between the Executive Branch and the Armed Forces are strained, particularly in the wake of the attempted coup on January 8, that was carried out with the collaboration and encouragement of the Cabinet of Institutional Security, which at the time consisted of military personnel loyal to Bolsonaro.

Illegal mining and First Capital Command (PCC)

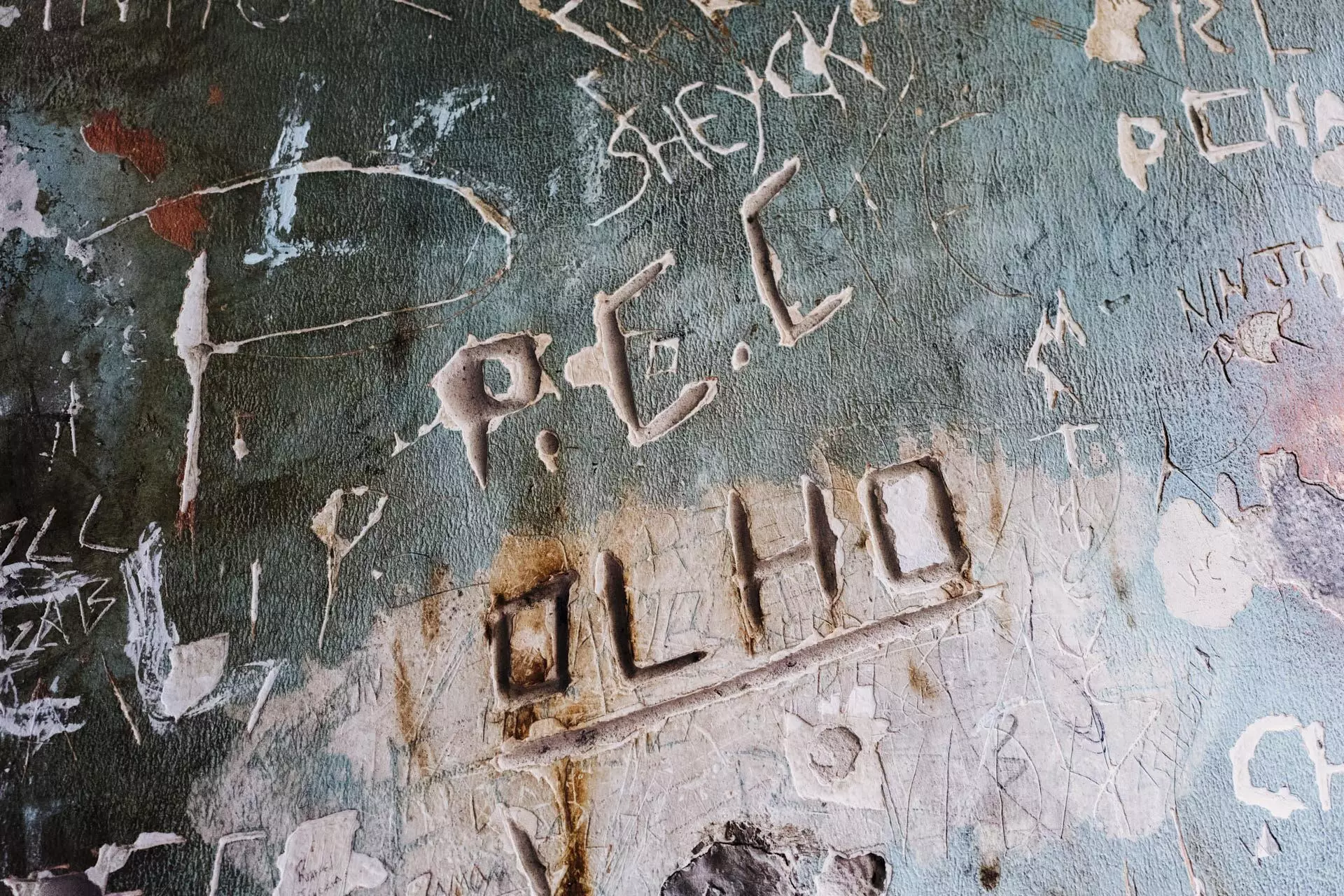

Detail of a wall with the First Command of the Capital’s (PCC’s) initials scrawled on it in a prison in the State of Roraima. Photo: Thiago Dezan/Farpa/Inter-American Commission on Human Rights

Criminal organizations are involved in mining in the Yanomami Indigenous Land for a number of reasons, but one important factor is the rebellions in the prison system of the cities in the North of Brazil in 2016 and 2017.

“We know criminal organizations arrived in the prisons of Boa Vista in 2013 and 2014. In 2016 and 2017, there was a war between the different factions and PCC got the upper hand in the region. I work under the assumption that the gang’s involvement with illegal mining starts off with prisoners who escaped from jail and used the illegal mining camps as a safe haven. And, once on the indigenous land, they can never go back”, said the researcher Colares. The use of clandestine airstrips in the territory by international drug-traffickers dates back further and has been going on at least since the 1990s.

If in 2017 there were already faction members engaged in drug trafficking in the region, little by little these criminal organizations began to realize they shared a synergy with environmental crime. “These two illegal economic activities [illegal gold mining and drug trafficking] came together inside the territory where there is no state presence, where it’s every man for himself,” declares Melina Riso, who is research director of the Igarapé Institute. She makes clear that the factions do not run the illegal gold mining itself, but rather they provide logistical support and protection: “The factions are not the owners of the whole operation, but they share the logistical structure of the illegal gold mining operations, they share aircraft. Whoever transports drugs, transports gold.”

In addition to the deliberate neglect of the Yanomami Indigenous Land by the Bolsonaro government, Riso lists several other factors related to the presence of the narco gangs: the dismantling of the agencies linked to environmental monitoring, gold’s appreciation on the international market, the excessive production of cocaine in recent years (which has had a negative impact on the price of the product), policies facilitating access to weapons and Jair Bolsonaro’s rhetoric in favor of illegal gold mining.

“Due to a number of factors, crime is looking for another type of economic activity. And gold is less risky, it is easier to launder, and there is absolutely no control whatsoever by the state,” is her assessment. “All in all, it is more advantageous.”

Spell check (Portuguese): Elvira Gago

Translation into Spanish: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Mark Murray

Photography editing: Marcelo Aguilar, Mariana Greif and Pablo Albarenga

Page setup: Érica Saboya