“Guys, let’s get going. It’s getting hot,” shouts João Maria dos Santos, a burly, bronzed fellow with thick black hair who directs Novo Progresso’s Municipal Department of the Environment. It’s only 8:30 on Wednesday morning, June 5, but in the municipality that ranked fifth in Amazon deforestation from 2008 to 2023, the blistering heat of the sun makes you suspicious of the thermometers registering “only” 80 degrees Fahrenheit (27oC). Following Santos’s orders, a cluster of some 20 people, most of them civil servants, gathers around Mayor Gelson Luiz Dill, of the Brazilian Democratic Movement. In celebration of World Environment Day, the city official is going to plant a dozen saplings in a park in Canaã, a neighborhood where small homes line dirt streets, about a mile from downtown.

“It seems like the sun gets one degree hotter every day. It’s a reality,” says gray-haired Dill, 52, originally from the southern state of Paraná. Dill, whose pale skin burns easily in the Amazon sun, will seek reelection in October. To take the edge off the heat, a water truck has damped down the streets along the route taken by the mayor and his staff. Within half an hour, the water has soaked deep into the parched earth or simply evaporated. After an evangelical pastor has “prayed for this administration,” Dill addresses the group. He explains that one of the trees being planted, an acacia, was chosen because it grows fast, so it can provide “shade as quickly as possible.” Next, after informing attendees of SUMAÚMA’s presence at the ceremony, Dill moves on to a demand that has mobilized Novo Progresso and the region for years: the call to shrink Jamanxim National Forest by 27%.

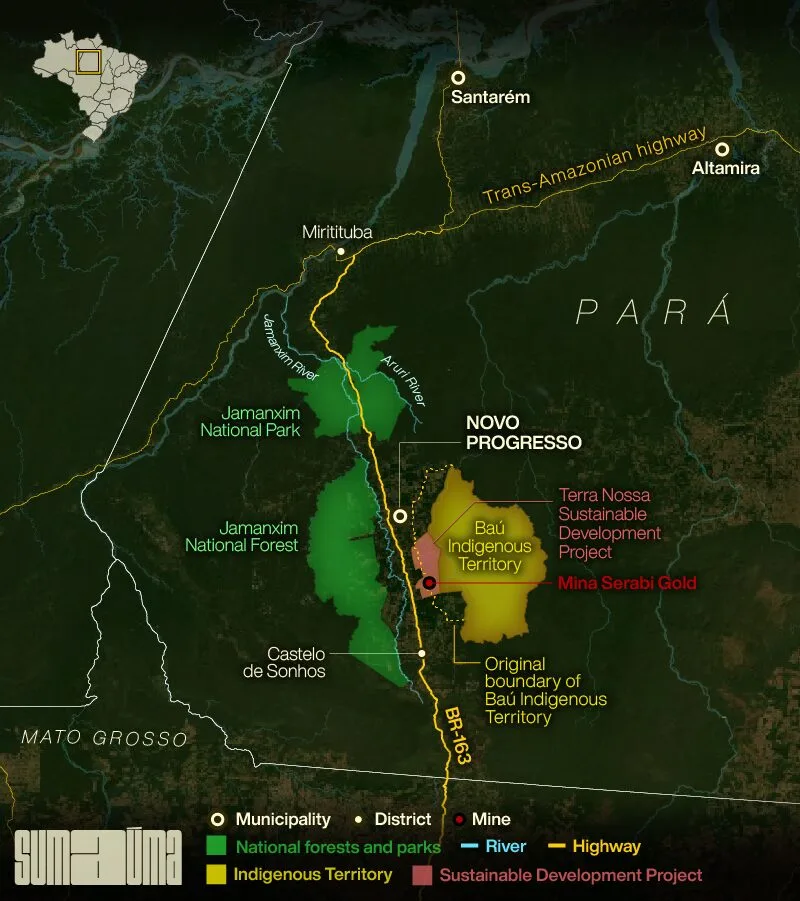

InfogrAPHIC: Ariel Tonglet/SUMAÚMA

Jamanxim National Forest was established in 2006. It is spread across more than 13,000 km2, almost eight times the area of London. It is part of a set of conservation units planned as an environmental offset to the surfacing of a 700-km stretch of federal highway BR-163, running north across western Pará state from the Mato Grosso border to the Trans-Amazonian highway. Completed in 2019, the asphalting project responded to demands from Mato Grosso soybean farmers, who wanted a reliable route for sending their export production to Miritituba Port, on the Tapajós River, where the asphalt ends. Prior to surfacing, clouds of dust rising from the dirt roadway in summer hampered visibility and slowed drivers down; in the rainy winter season, mud was the obstacle. The team at the Ministry of Environment, headed by Marina Silva during President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s second term of office, feared that the mere prospect of a surfaced thoroughfare would incite land thieves and illegal loggers greedy for public property lying along the highway.

That’s exactly what happened.

In addition to Novo Progresso, two other municipalities in Pará that highway BR-163 passes through are on the list of leading Amazon deforesters for 2008-2023: Altamira, home to the district of Castelo de Sonhos, holds first place, while Itaituba, seat of Miritituba district, ranks tenth. West of these three towns, edging close to the highway in a few spots, lies Jamanxim National Forest. The Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation, or ICMBio, an environmental agency that manages federal conservation units, estimates that there were “between 100 and 200” people occupying these federal public lands in 2006 when they became a national forest. This figure has risen sharply since then, with 494 “ranches” registered in Jamanxim, according to the national rural property database (CAR), where rural landowners self-declare the location of their property and provide environmental data on it. But in the Amazon, land thieves use the database to “certify” property lines and “ownership” of real estate that actually belongs to the public.

According to Mayor Dill’s calculations, the actual number of “rural landowners affected by the national forest” is even higher, something like 700 occupants. The term “rural landowner” is of course a linguistic ruse: the vast majority of these occupants are public land-grabbers who laid claim to the land after it became a conservation unit. These invaders are responsible for Jamanxim’s standing as the second most deforested conservation unit in the Amazon since 2008, eclipsed only by the Triunfo do Xingu Environmental Preservation Area, as reported by the Prodes satellite-based monitoring system, run by the National Institute for Space Research. Some 116,000 ha, or nearly 10% of the total area, have been cleared to make room for pastureland. It is estimated that at least 100,000 head of cattle are grazing in Jamanxim. Since a national forest is no place to graze cattle and, furthermore, since the Pará State Agricultural Defense Agency will not register animals raised on public land that is illegally occupied by private individuals or companies, it is easy to conclude that not a single one of these cattle is being raised in accordance with environmental or animal health regulations.

Torment: cattle walk a stretch of road where two destructive highways run together, BR-163 and the Trans-Amazonian. Photos: AVENER PRADO/SUMAÚMA

But the invaders are powerful people, admired in the region for their “entrepreneurial spirit” and well connected politically. So on May 16, when the Chico Mendes Institute launched an operation to seize cattle being pastured illegally in Jamanxim, it prompted an immediate, highly organized reaction. Even though the operation was in compliance with a recommendation by the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office, the governor of Pará, Helder Barbalho (Brazilian Democratic Movement), phoned Environment Minister Marina Silva and asked her to receive a delegation led by Mayor Dill, who had traveled to Brasilia to exert political pressure. In a written statement, the Pará government said it was “committed to dialogue and for this reason had coordinated talks between representatives of the Brazilian government and the local productive sector” in Novo Progresso, but that it “wholly supports the federal action to remove illegal cattle from ranches inside Jamanxim National Forest.”

A broad front against the forest

Local politicians and leaders of “rural producer” associations arrived at the Environment and Climate Change Ministry on May 22, escorted by parliamentarians representing the entire political spectrum, from the leftist Workers’ Party to far-right Bolsonarism. It was an intriguing entourage: federal deputies Airton Faleiro, from the Workers’ Party, and José Priante and Henderson Pinto, both with the Brazilian Democratic Movement; Senator Zequinha Marinho, from the Podemos (We Can) party; and former federal deputy José Geraldo Torres da Silva, aka Zé Geraldo, currently one of the Workers’ Party vice-presidents. Priante is the coordinator of the Pará caucus in the lower house and has close ties to the leaders of the Pará Agriculture Federation. The organization’s membership includes a number of “rural producers” from the Novo Progresso area.

Speaking before Minister Marina and Mauro Pires, president of the Chico Mendes Institute, Dill and his group defended approval of a bill submitted to the Chamber of Deputies in 2017 by former President Michel Temer—who, like the Novo Progresso mayor and Pará governor, is a member of the Brazilian Democratic Movement party. Under the proposal, nearly 860,000 acres (348,000 ha)—more than twice the area of São Paulo city—would be split off from Jamanxim. The detached piece of land would become an environmental protection area, a kind of conservation unit where private occupants can ask the federal government for title to the land they have deforested. In short, every land-grabber’s dream.

Broad front against the forest: clockwise from top left, deputies Airton Faleiro (PT), José Priante (MDB), and Henderson Pinto (MDB); Senator Zequinha Marinho (Podemos); and former deputy Zé Geraldo (PT). Photos: Vinicius Loures/Câmara dos Deputados, Mario Agra/Câmara dos Deputados, Jane de Araújo/Agência Senado, Zeca Ribeiro/Câmara dos Deputados

The bill, number 8.107/2017, never got off the ground, nor was a rapporteur ever assigned to it. Likewise in 2017, Temer sent the text of the bill to the Chamber of Deputies after vetoing his own provisional measure—much to the chagrin of the Pará caucus—which also would have shrunk the national forest. Priante had been the bill’s rapporteur in the lower house. In response to Temer’s veto, land-grabbers and loggers closed down highway BR-163 between Castelo de Sonhos and Novo Progresso, forcing the then-president to propose that Congress reduce the size of Jamanxim National Forest.

For an idea of the potential devastation this change in category might unleash, the most heavily deforested conservation unit in the Amazon is precisely an environmental preservation area, Triunfo do Xingu. While the latter unit is not much bigger than Jamanxim National Forest, 26% of its total area was cleared between 2008 and 2023. If the mere news that BR-163 would be asphalted over was enough to incite an invasion of land-grabbers, along with some 100,000 head of cattle, it’s not hard to calculate what would happen to this piece of the Amazon Rainforest if land thieves were certain the real estate they stole from the public would be transformed into legalized private property.

“Of course it’s fair,” Dill replied when journalists in Brasilia asked about the proposal he had presented to Minister Marina Silva. “It’s not stealing public land. That’s how Brazil was colonized. Where your house stands today, somebody [once] went there, cut down trees, and occupied it.” A few days later, under a blazing sun at 8:30 AM in Novo Progresso, the mayor gave a recap of the meeting and his proposal to the minister. Then he knelt down and planted an acacia sapling in honor of the environment.

“It’s not land-grabbing. It’s a settlement model”

“What good is a forest if it serves no economic purpose?” asks Gelson Dill about an hour later, back in his office. On one of the walls of his perpetually cool, climate-controlled office hangs a framed montage of the flags of Brazil and Pará. Each flag bears the autograph of a politician he admires and campaigned for: former president Jair Bolsonaro and current Pará Governor Helder Barbalho. The governor’s signature is preceded by a dedication: “All the very best to our friends in Progresso.”

Keeping company: Mayor Gelson Dill in his office. On the right, ambiance is provided by flags bearing the signatures of Jair Bolsonaro (PL) and Helder Barbalho (MDB). Photos: Avener Prado/SUMAÚMA

Progresso was what the town was called when settlers first came to the region in the early 1980s, drawn by the opening of highway BR-163. According to the City Council’s official website, the town sprang up “due to the construction of the Santarém-Cuiabá Highway, which tore up and deforested the Amazon Rainforest in 1973.” But in 1983, it was still just “a small village, with one church and a soccer pitch.” This all changed in 1984, when gold was discovered in the region, “drawing thousands of people to the area.”

It was gold mining that spurred the growth of Progresso, then a district of Itaituba, gold laundering capital of the Amazon. In 1991, the village became a municipality and “Novo” was added to its name to differentiate it from a town in Rio Grande do Sul. Novo Progresso had a population of around 5,000. “I consider myself a child of BR-163,” says Mayor Dill. He was three years old when, in 1975, his family left western Paraná, in southern Brazil, heading northward up the highway to Mato Grosso. They stopped in the city of Sorriso before moving to the small town of Nova Guarita, where Dill served two terms as a councilmember, representing the Democratic Labor Party.

In 1998, he packed his bags and headed north once again, to Novo Progresso, Pará, in search of land to occupy. He logged timber on public lands that are now part of Jamanxim National Park; this conservation unit, located north of Jamanxim National Forest in the municipality of Itaituba, was likewise created to mitigate the environmental impact of BR-163. There, he “established property” in 2002. He says he and two of his brothers have asked Brazil’s land and agrarian reform agency Incra to legally recognize 2,500 ha of land. The size of the property isn’t random: 2,500 hectares is the largest area that can be deeded by the federal government without congressional authorization. What isn’t clear, however, is whether the 2,500 is the sum of three lots, or if the siblings are trying to register three contiguous areas of this size, which in practice could constitute a large landholding known as a latifúndio—a common strategy for stealing huge tracts of land in the Amazon. When asked about this, the mayor did not reply. What the Dill brothers have requested is what many others along BR-163 would like as well. When asked by SUMAÚMA, the land reform agency said there are 1,500 requests for land recognition along the 700 km of BR-163 stretching from the Mato Grosso-Pará border to the Trans-Amazonian highway. The agency’s figure does not include plots that overlap conservation units, such as Jamanxim National Forest.

Gelson Dill has already been fined three times by the Chico Mendes Institute for illegally clearing nearly 200 ha in Jamanxim National Park. His total fines surpass BRL 2.4 million ( USD 440,000). Brazil’s environmental protection watchdog Ibama also embargoed an area of roughly 89 ha. In 2020, during his mayoral campaign, Dill informed the Electoral Court that he “owned” two ranches located inside Jamanxim Park, where he was raising 2,473 head of cattle, which he valued at BRL 1.9 million (USD 350,000). “I don’t consider this land-grabbing, because it’s been the settlement model across practically all of the Amazon,” the mayor argues. “These people were called here, to occupy a piece of ground.”

Dill is replicating a strategy that land-grabbers in Novo Progresso employ quite purposefully to create confusion in their favor. The business-military dictatorship (1964-1985) did indeed summon Brazilians, mainly from the Northeast and South, to colonize areas along the Trans-Amazonian highway. The effort was part of an initiative called the Integrated Settlement Project, designed by the dictatorship to reduce pressure for land reform in southern Brazil and at the same time occupy the Amazon, home to Indigenous peoples, Ribeirinhos, and Quilombolas, along with thousands of non-human species. The project slogan was “Integrar para não entregar”—integrate so as not to surrender the Amazon to foreign interests. But the project stopped 200 km north of Novo Progresso, in the Aruri River Valley, during the 1970s.

Urban scene: men rest by the side of highway BR-163 in Novo Progresso, while a bulk truck heads toward Miritituba Port. Photo: Avener Prado/SUMAÚMA

On another front, limited to Mato Grosso, private companies built towns and claimed farmland at the dictatorship’s behest. That’s why municipalities like Sinop, Confresa, Colniza, and Colíder bear the names of their colonizers. In Novo Progresso, the conventional wisdom is that the town’s “rural landowners” moved there to answer the government’s call to integrate rather than hand anything over. But that’s not true. By the time the land rush gained steam in Novo Progresso, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the dictatorship and the Integrated Settlement Project were history.

“Along this stretch of federal highway BR-163, occupation by settlers, primarily from the South, was entirely spontaneous. In other words, outside the bounds of official settlement programs. However, when the region of Novo Progresso was settled, somehow the notion was that land lying 10 km on either side of the road was reserved for settlers,” write researchers Mauricio Torres, Juan Doblas, and Daniela Fernandes Alarcon in a lengthy study on the relation between land-grabbing and deforestation in southwestern Pará, published in 2017 by the Amazon Agronomy Institute.

In Novo Progresso, the basic purpose of politics is to defend the interests of public land thieves. “When I moved here, I didn’t want to get involved in politics anymore. But within four years I was asked to serve on the board of the Rural Association, where I’ve been for 20 years. And there they said: why don’t you put your name in [for the elections]?” Dill explains. A few days earlier, in Brasilia, after his meeting with Environment Minister Marina Silva, he made it clear why he changed his mind: “The job I’m doing, as mayor of Novo Progresso, is to fight for all the producers in the BR-163 region.”

Enemy fire: Minister Marina Silva (foreground, center) received the delegation led by Mayor Gelson Dill, in Brasilia, at the request of Governor Helder Barbalho (MDB). Photos: Ascom Novo Progresso & Marco Santos/Agência Pará

Not that the town doesn’t have problems. With a population of 33,638, according to the 2022 census, Novo Progresso has connected only 1.4% of its households to a sewer system, and only 8% of its streets have adequate tree cover (these figures are from 2010, because the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics has yet to compile data from its latest survey). With 15.45 deaths per 1,000 live births, the town places 1,808th in infant mortality out of Brazil’s 5,570 cities. Among the 144 cities in Pará, it ranks 56th.

A survey called the Social Progress Index (IPS) for the Amazon, produced by the Amazon Institute of People and the Environment (Imazon), compares the quality of life in municipalities within this biome, based on 12 social and environmental criteria. The study found that places that have experienced more recent deforestation performed poorest. “The 20 municipalities displaying the highest recent deforestation rates account for more than 50% of the area deforested in the period [and] the vast majority have a very low IPS,” says the latest study, from 2023. According to the same survey, Novo Progresso ranks 637 out of the 772 municipalities making up the Legal Amazon. The town scores poorly on such criteria as public safety, school drop-out rates, water supply, and carbon dioxide emissions. Locally acclaimed as a vector of development, the asphalted highway hasn’t helped. “Municipalities along highway BR-163 in Pará score low” in what the survey classifies as “Basic Human Needs — Nutrition and Basic Healthcare, Water and Sanitation, Housing, and Personal Safety.”

Moving backward: aerial view of the Fire Day capital, which has one of the worst quality of life scores in the Amazon, according to the NGO Imazon. Photo: Avener Prado/SUMAÚMA

Courts rule against the forest

The Ferradura Ranch occupies a little under 1,900 ha of deforested land inside of Jamanxim National Forest. It is the epicenter of an operation by the Chico Mendes Institute, commonly known by its acronym ICMBio, to remove cattle being raised illegally in the conservation unit. Launched in May, the operation has a 60-agent task force that also includes the National Public Security Force, the Federal Highway Police, and the Agricultural Defense Agency of Pará.

It is often said in Novo Progresso that Ferradura “belongs” to José Pereira. Yet although the area boasts 64 km of barbed wire fencing, corrals, a house and bathroom for cowhands, and an antenna several feet tall for internet access, it is not registered in the national Environmental Registry of Rural Properties, known as the CAR. There, ICMBio agents found 2,058 head of cattle being raised illegally. The animal ear tags led the environmental agency to suspect they would be sold to meatpacking plants in the name of Arara Azul, a different property, located outside of the national forest.

The 2,058 head of cattle belong to Rodrigo da Cruz Pereira, José Pereira’s son. They did not have the health records required by the Agricultural Defense Agency of Pará. Yet before the environmental agency could seize them, Rodrigo was granted a preliminary injunction by 1st Regional Federal Appellate Court justice Eduardo Filipe Alves Martins. In a ruling rendered on May 22, Rodrigo was appointed the “bona-fide depositary” of the cattle he was raising illegally in a public area. A few hours afterward, he removed the animals from Ferradura, with agents unable to do anything about it. The appellate judge is the son of Humberto Martins, a judge who sits on the Superior Court of Justice and was considered for a spot on the Federal Supreme Court during the far-right Jair Bolsonaro (Liberal Party) administration. In March 2024, during his time with the 1st Regional Federal Appellate Court, Eduardo Martins promised his office would be “the embassy of the legal profession.” SUMAÚMA put in two requests to interview the appellate judge, to understand the reasoning behind his ruling. Both were ignored.

Opening the gates: appeals court justice Eduardo Martins and the Ferradura Ranch, operating inside of the Jamanxim National Forest, where seizures of illegal cattle have been prevented thanks to a ruling by the justice. Photos: Ruy Baron/BaronImagens and Avener Prado/SUMAÚMA

The Búfalo Branco and Cancioneiro “ranches,” which lie across the fence from the Ferradura, are enrolled in the CAR under the name of Sandra Mara Silveira and cover nearly 4,000 ha of contiguous—and deforested—land. Despite being listed and registered in the CAR, they are actually misappropriated public areas within the conservation unit. This happens because the CAR is a self-declared registration—which means the system will let anyone claim to “own” any piece of ground in the country. The lands registered in the CAR under Sandra’s name were placed under ICMBio embargo 11 times from 2015 to 2022. According to a survey by Agência Pública, she was the top recipient of environmental fines for destroying vegetation across all Amazonian conservation units from 2009 to 2021, landing a total of USD 18 million (BRL 96 million) in penalties.

Environmental agents suspect another area also belongs to Sandra and her husband. Covering over 4,100 ha, it lies adjacent to the “ranches,” is not registered in the CAR, and 2,900 ha have already been deforested and embargoed. ICMBio is investigating whether 3,500 head of Sandra’s cattle, raised without health records, are roaming freely between the two “ranches” and the neighboring area. However, these cattle were also not seized, thanks to another court order, handed down this time by federal trial court judge Lorena de Sousa Costa, in the judicial district of Itaituba. Justice Sousa Costa did not respond to SUMAÚMA’s request for an interview.

“There was a procedural mistake at ICMBio in the administrative process,” argues attorney Pedro Henrique Gonçalves, who is representing Sandra and Rodrigo in court. “Correct notice was not given and there was not an appropriate legal process,” he argues—and a federal judge and a federal appellate judge found in favor of his argument. The environmental agency, in turn, refutes his assertions. “In all of the cases brought against the aforementioned parties, due legal process was followed, with entitlement to a full defense and informing [them] of notices of violation,” the agency said in a statement sent to SUMAÚMA. “ICMBio has done a very precise job, on properties—not properties, occupations—that are undeniably illegal, that are not in the Environmental Registry of Rural Properties, that operate outside of health laws, and where all appeals have been exhausted in relation to embargoes [in the administrative sphere],” said Minister Marina Silva following a May 22 meeting with Mayor Gelson Dill. SUMAÚMA asked the attorney for an interview with the couple suspected of stealing public lands but was told they did not wish to speak.

“Pressure to re-categorize conservation units in order to make land use rules more flexible has been an increasingly common mechanism in the Amazon and is part of a strategy of trying to legitimize illegal occupations, without any legitimate title of ownership, accompanied in large part by deforestation of large swaths of forest,” says federal prosecutor Isadora Chaves Carvalho. She is following the Jamanxim operation through the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office in Pará and attributes the Novo Progresso land-grabbers’ boldness “to the historical process of disorderly occupation in the Amazon” and to the “government’s ineffectiveness at managing its own lands”—that is, both conservation units like Jamanxim National Forest and undesignated public lands, the main target of land-grabbing. “Revising the boundaries of a protected space is not the solution to problems. To the contrary, it could serve to encourage more invasions in the region, since it will work to reward clandestine occupations and misappropriation of public lands, not to mention negative social aspects, such as greater pressure on forest peoples,” she emphasizes.

While the Lula administration and the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office are working to overturn these rulings, the land-grabbers take the opportunity to remove their cattle from the Jamanxim region. If, on the one hand, this guarantees that illegal occupation of the area is stopped (at least momentarily), on the other it thwarts one of the main goals of operations like the one carried out by ICMBio in Jamanxim: decapitalizing environmental criminals. While ICMBio agents wait, they are working within the tight limits of court rulings, doing things like destroying the fences used by illegal ranches inside of Jamanxim.

Even so, they receive threats. On June 13, a video circulated on Novo Progresso residents’ cell phones, causing a stir on the city’s online news portals. In the recording, shot partly from inside of a pickup that looks to be new (and expensive), a man confronts a National Public Security Force agent and tells him “you all had better go back and get informed” about the Itaituba court ruling before knocking down the Cancioneiro “ranch’s” fences. That man is Márcio Piovezan Cordeiro. SUMAÚMA learned that the next day, he and Sandra filed a police report against ICMBio, which was hand-delivered to agents working at the Ferradura Ranch by Marcelo Diniz Santos Filho, a chief of police with the Novo Progresso Civil Police force.

Two sides: livestock farmer Sandra Mara Silveira, the owner of cattle raised illegally in Jamanxim National Forest, and Marcelo Diniz Santos Filho, the chief of police who delivered a police report to ICMBio agents. Screenshots: Facebook and TV Progresso

In any case, once the operation is over, deforested areas in Jamanxim National Forest will be quite prone to renewed invasion by land-grabbers. And they can count on ICMBio’s lack of structure in the region. The agency has no offices in Novo Progresso. Its closest unit is the Special Advanced Unit of Itaituba, 397 km down highway BR-163. The 77-person team—only 19 of whom are career public servants—is responsible for enforcement in 12 conservation units spread across western Pará and a small part of eastern Amazonas state, totaling over more than 9 million ha. It is an area comparable to the size of Portugal, except units are not contiguous and are hard to access. Making matters worse, environmental agency workers went on strike indefinitely in 17 states (including Pará) starting June 24, after nearly six months of waiting for the Lula administration to submit a satisfactory wage readjustment and career restructuring proposal. The government petitioned the courts—successfully—to rule the stoppage illegal, yet some workers remain on strike.

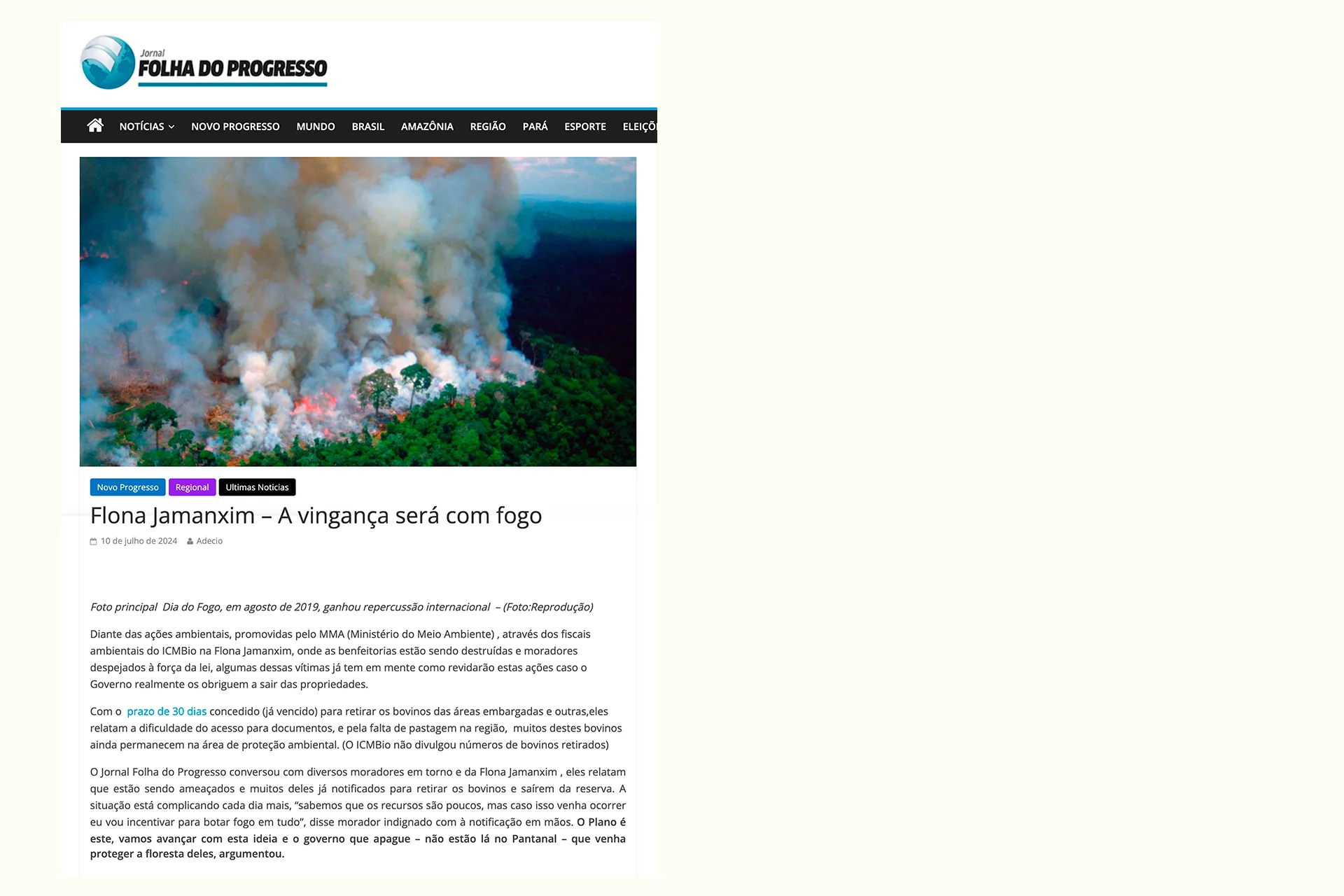

July 10 article in the newspaper Folha do Progresso: Land-grabber promises fires as ‘revenge’ for fight against environmental crimes”

In early July, a Novo Progresso newspaper ran a story about an unidentified land-grabber threatening to set fire to Jamanxim National Forest, in retaliation for the ICMBio-issued orders to remove illegal cattle. It would be another Fire Day, the name given to an August 2019 event when Novo Progresso’s ruralists, empowered by the Jair Bolsonaro administration, set fire to several stretches of forest along BR-163. “I’m going to encourage setting fire to everything,” the land-grabber told the Folha do Progresso newspaper. “Here’s the plan. We’re going to move forward with this idea and let the government put it out—aren’t they there in the Pantanal?—let them come and protect their forest.”

Mauricio Torres, a co-author of the Amazon Agronomy Institute study on land theft and deforestation, explains the land-grabber rationale: “In the Amazon, conservation units and Indigenous territories are major barriers to deforestation. Just look at satellite images and you’ll see that the devastation’s advance doesn’t obey the topographical or soil quality criteria or any other technical element; rather, it steals into protected areas, through undesignated public lands. When a public area is designated, making it a conservation unit or Indigenous Territory, it is no longer possible for the public to stop owning it so it can be privatized, appropriated by an individual, and integrated into the real estate market.” Torres is a social scientist and a professor and researcher at the Federal University of Pará, where for years he has studied the state’s land conflicts, the topic of his doctoral thesis. “The problem with Jamanxim National Forest is the federal government has already indicated that it could be pared back. The land, in this case, would again become available for private appropriation, which would create a rush for control of these areas. We know deforestation is the main instrument land-grabbers use to appropriate and control land,” he explains. Torres accompanied SUMAÚMA on its trip to Novo Progresso for this report.

When asked, the ICMBio press agent responded that “Jamanxim National Forest is different from other [units of this kind], particularly because of its history of occupation and the profile of occupiers, who came from southern Brazil, encouraged by federal programs at the time to populate the Amazon under the slogan of integrating to avoid surrendering the region to foreign interests.” In other words, the environmental agency is itself buying the land-grabbers’ version. “Some of Jamanxim National Forest’s occupants aren’t interested in creating the conservation unit, creating difficulties in the evidentiary stage of land regularization, not taking part in the advisory committee and, in some cases, encouraging land-grabbing and deforestation in the region. These groups are well connected politically and have good lawyers who use the courts to ensure their permanence, even in opposition to current environmental laws,” the press agent says. “Negotiations continue underway to implement sustainable activities through a forestry concession in Jamanxim National Forest (via the Brazilian Forest Service), in a federal government effort to find alternatives that will generate income in conjunction with sustainable development in the region,” the statement ends.

Rape: an area ravaged by public land thieves for illegal cattle grazing in Jamanxim National Forest: Avener Prado/SUMAÚMA

“Is everyone here an idiot?”

The land-grabbers’ bold forays into Jamanxim National Forest are spurred by a historical precedent. In October 2003, during the Lula administration’s first year, pressure from public land invaders in Novo Progresso led the Ministry of Justice to accept an “agreement” that swiped nearly 300,000 ha, or 17% of the total area, from the Baú Indigenous Territory, a traditional territory of the Mebêngôkre Indigenous people, better known as the Kayapó among the non-Indigenous. The Baú Indigenous Territory lies to the right of federal highway BR-163, while the national forest sits on the left side. In exchange, and with the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office’s stamp of approval, the “ranchers” have promised to pay USD 22,000 (BRL120,000) per year, over ten years, to the municipal government of Novo Progresso, an amount that is supposed to be invested in “benefits” for the Indigenous people.

Capitulation was achieved through threats of violence. In September 2003, a group of a thousand people, mostly land-grabbers and miners, blocked traffic along the stretch of BR-163 that runs through Novo Progresso. The city’s businesses closed their doors amid reports that armed men had gone into the forest and were prepared to remove by gunpoint workers with the Indigenous affairs agency, Funai, who were carrying out the physical demarcation of the Indigenous territory. “The win from their pressure to reduce the Baú Indigenous Territory taught land-grabbers they can get what they want with threats and violence,” says Mauricio Torres. “After that achievement, they set their sights on Jamanxim National Forest, using the same strategies.”

Leading the movement against the Baú Indigenous Territory was Agamenon Menezes, then the president of the Novo Progresso Rural Producer Association—in fact, he was the one who invited the mayor, Gelson Dill, to join the organization’s board. Menezes has authored statements like this one, from 2008: “Do they [NGOs] think everyone here is an idiot? Stupid? Ribeirinhos who eat vines and hearts of palm?” A penchant for violence has never kept him from accessing seats at entities like the Pará Agriculture Federation or the Agriculture Federation of Brazil. Currently suffering from a neurodegenerative disease, he is no longer association president but remains active. In June, SUMAÚMA visited his home in Novo Progresso to speak with him. We were told he was in the state capital, Belém, for a “ruralist meeting.” He is also one of the suspected leaders of Fire Day, but he denies the fires were planned.

The area excised from the Baú Indigenous Territory became a haven for land-grabbing and deforestation. It is where Torres finds “the greatest individual case of deforestation on record in the Amazon in the last three decades:” an area of over 30,000 ha that has been appropriated by cattle rancher Antonio José Junqueira Vilela Filho, or AJ Vilela, who also goes by Jotinha. The son of an award-winning rancher who graces industry magazines and the ex-husband of a jewelry designer whose customers include celebrities like Madonna, Jotinha lives in the upscale neighborhood of Jardins, in São Paulo—which is why he is called the “land-grabber of Jardins”—he is rarely at his “ranch.”

“The 30,000 hectares are totaled from the deforestation notifications he has received, based on data from the Prodes satellite-based monitoring system and on georeferenced information obtained in the field, and this would make him the biggest individual agent of deforestation in the Amazon since clearing began to be monitored,” says Torres. Based on the deforestation and other accusations, USD 78 million (BRL 420 million) of Jotinha’s assets were blocked, he was arrested, and he is being taken to court by the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office.

Faithful portrait: mining, cattle ranching, logging, and soybeans are featured on Novo Progresso’s coat of arms; on the right, a truck hauls logs down BR-163. Reproduced from the Novo Progresso City website. Photo: Avener Prado/SUMAÚMA

Asked for comment, he said that “all of the infraction notices have defects and nullities,” that the courts have voided fines related to deforestation of 15,000 ha, and that he hopes others will also be voided. He also said that accusations of criminal organization made against him were not “even allowed by the judge” in the case and he threatened to sue SUMAÚMA if our reporting “failed to tell the truth.” The Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office says it “has reiterated to the federal courts that environmental damages are clearly documented and there is a causal relationship to the defendants’ actions, and that all preexisting evidentiary elements are sufficient to establish the occurrence of environmental damage, identify those responsible for illegal acts, and establish a cause-and-effect relationship. Even if any evidence is voided, it does not make the entire consistent body of evidence invalid.”

Attorney Soraya Saab, who is representing Jotinha in the lawsuits, says that “Antonio is neither the owner, holder, nor possessor of any rural property in the disappropriated area of the Baú Indigenous Territory, and the accusations made by [environmental agency] Ibama are completely false and without any grounds or evidence.” She also said that “the courts have not even allowed accusations of criminal organization, giving you an idea of the great injustice that was committed based on false news of the deforestation of more than 13,000 hectares that never existed.” A total of seven lawsuits were filed as a result of the operation in which Jotinha was charged and arrested. He stands accused of environmental damage, exploitation of forced labor, and money laundering. All of the suits are pending trial in the lower court.

The area of the Baú Indigenous Territory the federal government took from the Kayapó is also home to the Terra Nossa Sustainable Development Project. This is a settlement of small farmers organized in 2006 by Incra, Brazil’s agrarian reform agency, and is one of the few land reform initiatives in the Novo Progresso region. Nevertheless, most of the 150,000 ha planned to hold 300 families of small farmers has been stolen by land-grabbers or is being held by a mining company. That is why a few dozen families are squished into an area of under 8,000 ha and have yet to receive the titles to their land.

The mining company is Serabi Gold, based in the U.K. and operating the Coringa project mine without a license from Incra and without consulting the Indigenous people in the Baú Indigenous Territory, as required. On the road to Terra Nossa, SUMAÚMA came across an enormous truck loaded with ore mined by Serabi—residents say they are constantly driving down local roads. The company says it is “completely comfortable with [its] legal position” and that it complies with the legal framework of Brazilian mining and is authorized to operate.

Despite occupying less than 10% of the original settlement area, the residents of Terra Nossa have reported a profusion of threats being made and the murder of four of their leaders since 2017. This happened to Cleve Gonçalves da Silva, or Tiririca, as everyone calls him, a 61-year-old from Ceará who came to the region as a young man to try his luck in mining. “I was fleeing drought when I came here. Mining, I picked up more malaria than gold. I quit. I’ve been here at Terra Nossa 15 years,” he says, next to the shabby little wooden house where he lives, built on a lot where he plants a small area of crops and raises a few animals to survive.

A while ago, an influential lawyer in the region invaded and deforested an abandoned lot next to his. Later, she moved her fence inside of Tiririca’s property. He says he was beaten when he complained and then taken to a Pará Military Police station along BR-163, where he was allegedly photographed and handcuffed. Tiririca filed a police report related to these events. SUMAÚMA learned that the police accused of assaulting the settler had been transferred from Novo Progresso. The fence that consolidated the alleged theft of a roughly 90 by 400 m area remains, however.

Threatened: Cleve Gonçalves da Silva, known as Tiririca, standing atop a post of the fence that invaded his lot in the settlement of Terra Nossa. Photo: Avener Prado/SUMAÚMA

Another Terra Nossa resident, Maria Márcia Elpídia de Melo, 46, is the most active in defending the settler’s rights. She says she has received death threats because of it. “They’ve already come by and shot at my house,” she says. “Another time they chased me, and I had to hide in the woods to escape.” Her fear that they could simply make her disappear was why she tattooed a picture of her son José Rael, 27, on her chest in October of last year. In the Amazon’s Social Progress Index, Novo Progresso is among the 12 worst municipalities out of 772 in the region when it comes to public safety. Tiririca and Maria Márcia are part of a state program to protect human rights defenders. Yet they are rarely visited by the agents who are supposed to ensure their safety.

That is probably why there are no popular leaders or labor unionists active in the city. The last known combative trade unionist, Ivone Alves, shuttered her organization, which represented rural workers, after her daughter married a mining boss. SUMAÚMA went to her cozy house on one of the city’s main streets. She was not home—or she did not wish to answer the door. One block away is the first large monument raised in the city: an 2.5 m concrete statue of a miner holding a gold pan. Its creator, Apolinário Oliveira, a locally famous artist, is another victim of the violence in western Pará: he died of complications from a gunshot wound he received in 2020 while at an election party for a municipal council member in Santarém.

Taking precautions in the Amazon: defender Maria Márcia Elpídia de Melo has a tattoo of her son on her chest, for fear she might be murdered and not identified. Photo: Avener Prado/SUMAÚMA

Jamanxim’s land-grabbers live far away

Not only do they talk about heeding the call to populate the Amazon, one of the chief arguments wielded by Mayor Gelson Dill and by those who defend transforming part of Jamanxim into an environmental protection area is that in 2005, when the Legislative Assembly of Pará decided to pass a law on the state’s macro-zoning, the region along highway BR-163 was to be designated for economic expansion of the productive sector. And this is despite the fact that all of the lands there are federal. It is an argument that is easy to topple, says social scientist Mauricio Torres. “The federal government has the autonomy to designate its lands, especially when they fulfill a constitutional provision like, for instance, Indigenous territories,” he says.

The argument that the occupants of Jamanxim National Forest are small farmers who survive by farming the land they occupy also does not hold water. In 2009, ICMBio sent a team into the field with the mission of carrying out a study on the forest’s occupation profile. The survey concluded that 90% to 100% of “squatters” were businessmen living in the country’s South, Southeast, and Center-West who were paying employees to run their “farms” or residents of Novo Progresso or Castelo de Sonhos whose relatives oversee national forest invasions but have outside businesses. The “properties” varied from 1,500 to 50,000 ha—much larger than could be managed by a small farmer and far beyond what can be legally deeded to others through land regularization programs.

“Very few squatters are effectively residents of the national forest area, estimated by the team as being around 30 to 40 families in the entire unit,” the document says. Finally, the study suggests removing somewhere around 22,600 and 35,000 ha from Jamanxim, which would “provide better unit management capacity and would remove an area with major social appeal and environmental impact generated by both [illegal] mining and existing small properties.” This is an area ten to 15 times smaller than the nearly 348,000 ha coveted by Novo Progresso’s politicians and “rural producers” and established in a bill sent to the National Congress by Michel Temer.

It does not matter to the land thieves or to the broad political front supporting them in Brasilia. Meetings have been held in the city between politicians and rural producers since the ICMBio operation began. At the last one held before this report was filed, on June 17, Federal Deputy Henderson Pinto guaranteed that he and his colleagues Airton Faleiro and José Priante are working to move Michel Temer’s bill forward.

None of the three politicians wished to give an interview to SUMAÚMA about this case. While Zé Geraldo, Workers’ Party vice president, did speak—in defense of the proposal. “There’s no way to get those people out of there. The vast majority have a vested right. The government declared [it a national forest] and never tried to find a solution. I’m an advocate for the proposal to turn the area into an environmental protection area.”

In 2022, 83% of Novo Progresso’s voters voted for Jair Bolsonaro during the presidential run-offs—proportionally his largest margin of victory in Pará. After the far-right candidate’s reelection loss, protestors cut down a hundred-year-old Brazil Nut Tree to block BR-163 and they even attacked Federal Highway Police teams. A dispute was set off in the city to see who is most aligned with Bolsonaro. Aware of this, Senator Zequinha Marinho, a Bolsonaro supporter and defender of the invaders of the Ituna/Itatá Indigenous Territory, also in Pará, is backing the mayoral candidacy of Juscelino Alves Rodrigues, a former mayor and Social Democratic Party member. On the slate with him is Ubiraci Soares Silva, aka Macarrão, who formerly served as a Workers’ Party councilmember and a Social Christian Party mayor. Both are connected to illicit mining: Juscelino was a pilot and Ubiraci manages a shop in the city that buys gold, Macarrão Metais. Ubiraci has also previously been indicted for the “crime of money laundering and usurpation of federal public assets, in light of the illegal extraction of ore,” according to Repórter Brasil. Both are now affiliated with the Podemos party and are advertising themselves as “an alternative to the right” of Gelson Dill. The current mayor responds: “They’re not 100% right-wing. Macarrão was with the Workers’ Party. Juscelino was never involved in coordinating Bolsonaro’s campaigns here. I was, with both.”

This means there are two favorites to win the dispute for Novo Progresso’s mayorship in October. One is the incumbent, who is defending and is possibly connected to misappropriation of public lands and who is backed by Governor Helder Barbalho. In opposition are candidates suspected of involvement with illicit mining who are backed by one of Jair Bolsonaro’s most radical allies in the Senate. The Workers’ Party, in turn, is seeking shelter on Gelson Dill’s slate of candidates, as confirmed by the party’s municipal president, Aldecir Nardino, a native of Rio Grande do Sul who claims to be the first occupant of the area that is now Jamanxim, having arrived in 1979. The Brazilian Democratic Movement is fighting back. “For three terms now we haven’t had a councilmember. It’s hard for me to even get 12 candidates together,” Nardino says. Put another way: even though the Workers’ Party is advocating for the conservation unit’s reduction, its support is undesirable.

Monument: at the intersection of two main avenues in Novo Progresso, this statue celebrates mining, the activity that made the town. Photo: Avener Prado/SUMAÚMA

Neri Prazeres, a member of the Brazilian Democratic Movement party and Novo Progresso’s first-ever mayor, who is to this day considered its most influential political leader, is close to the Barbalho family and is backing Dill’s candidacy. A director of the Novo Progresso Rural Producer Association and a board member of the Pará Agriculture Federation, he is also one of the agents behind the tiny town’s pressure on Belém and Brasilia—and against Jamanxim National Forest. On a Sunday in June, he posted a 2017 speech to social media that was given by Senator Jader Barbalho, the father of Governor Helder Barbalho, arguing for Temer’s provisional measure.

SUMAÚMA requested interviews with Zequinha Marinho, Juscelino Rodrigues, and Macarrão. None of them wished to speak with us. But the municipal president of the Podemos party, councilmember Chico Sousa, did grant an interview. A native of Ceará who migrated to the region to try his luck at mining, he says he previously voted for Lula and Dilma Rousseff. He became a staunch Bolsonaro supporter “because of the thievery” of the Workers’ Party. Adorning his desk is a copy of Tchau, Querida: O Diário do Impeachment – Bye, Dear: Diary of the Impeachment, loosely translated – penned by former federal deputy and Dilma Rousseff critic Eduardo Cunha, a former member of the Brazilian Democratic Movement who is currently with the miniscule Democratic Renovation Party.

Sousa swears that he no longer works with mining and that he has never been involved with land-grabbing or agriculture. And he has a curious slant on the return of environmental enforcement, starting in 2023. “Lula is incredibly mad at us here, because they put up posters saying he is a crook throughout the region here. And then he said: ‘Nobody’s going to mine, nobody’s going to knock down timber,’” he argues. His view of the Jamanxim issue is emblematic of the thinking in the region. “Because of international pressure, they created reserves on top of places that were already owned. Our Brazilian people are very easy-going, very quiet, very calm, very passive. If this here were another country, we would have had a civil war there, a lot of government agents would have died already, a lot of civilians would have died already.”

Councilman: Chico Sousa (Podemos) thinks environmental oversight actions are Lula’s revenge for being called a ‘thief’ on posters in the region. Photo: Avener Prado/SUMAÚMA

“Tarcísio is different, you know?”

Few men are as admired in Novo Progresso as Ezequiel Antônio Castanha. Originally from São Paulo, he arrived in the region poor and today owns the only two large supermarkets in town, where he is seen as an “entrepreneur,” a fellow gutsy enough to do what has to be done—that is, deforest public land and put it up for sale. Because of this, he was arrested in 2015 and accused of leading a group that investigators called the largest crime organization specialized in land-grabbing and environmental crime in the Novo Progresso region. He spent six months on the run, after the Federal Police launched an operation fittingly baptized “Castanheira”—Brazil nut tree.

Here’s a gauge of Castanha’s status in the region: less than a month after his arrest, his cell in Itaituba was found to have been outfitted with gym equipment, a coffee maker, a minibar, a laptop with internet access, and a printer—all with the knowledge and complicity of prison administrators. Charged by the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office, the land thief and supermarket owner was sentenced to two years in prison for “forest degradation on lands in the public domain without the authorization of the appropriate agency.” Yet the federal courts in Pará only ordered him to pay fines and serve alternative sentences on probation. The prosecution has appealed, and the case awaits a decision by the Regional Federal Appellate Court in Brasilia.

Meanwhile, Castanha is moving about Novo Progresso and pursuing his work freely. Late afternoon on Wednesday, June 5, SUMAÚMA went to see him at one of his stores. After waiting a few minutes, he showed up. Brawny, about 1.9m tall , Castanha is a cordial man, soft-spoken and articulate. He refused to record an interview but chatted for a few minutes, standing outside the store. That was time enough for him to attack Marina Silva: “She’s not a minister of Brazil. She works like she’s a minister of Europe.” Castanha then defended the land-grabbers of Jamanxim National Forest: “When they created the reserve, there were already folks there. As long as there are no documents for the land, they’ll keep on deforesting it. But the left doesn’t want anyone to have documents.”

Our conversation was winding down when Castanha hinted that he’s pinning his hopes on the same president as the São Paulo bankers dressed in designer clothes who drink trendy coffee and expensive wine and hoverboard their way down Avenida Faria Lima, the financial heart of the city. “I like the right, but I’m with Tarcísio [de Freitas, governor of São Paulo], not Bolsonaro. Not Bolsonaro, not Lula—it’s hard to believe those guys were ever president. But Tarcísio, this guy’s mind… Tarcísio is different, you know?” Then Castanha said goodbye, climbed into a silver pickup with his wife, and headed down the BR-163.

Found souls: Evangelical service held in a bar in Novo Progresso’s brothel district, one of the busiest in town. Photo: Avener Prado/SUMAÚMA

Report and text: Rafael Moro Martins

Editing: Eliane Brum

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão and Soll

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Spanish translation: Julieta Sueldo Boedo

English translation: Diane Whitty and Sarah J. Johnson

Infographic: Ariel Tonglet

Copyediting and finishing: Natália Chagas

Editorial workflow: Viviane Zandonadi

News editor: Malu Delgado

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum