Aldo Rebelo, a member of congress for the Communist Party of Brazil for 24 years, and four times a government minister under Workers’ Party presidents Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and Dilma Rousseff, has won over the land grabbers and rural landowners of Altamira – until last year the firm support base of Brazil’s previous president, Jair Bolsonaro. The city in the state of Pará, situated in the heart of agrarian and environmental conflict close to the Trans-Amazonian Highway, has since January been the second home of the primarily São Paulo-based politician. From his office in the city on the banks of the Xingu River, where Jair Bolsonaro won 62% of the votes in last year’s presidential election second round run-off, the Panama hat-wearing Aldo has been traveling the Amazon to promote a “political project” in which he disputes the Lula government’s climate and environment agenda. Despite expectations among his supporters that he might put himself forward as an alternative to Bolsonaro, Aldo denies any electoral ambitions, and says his attention is focused on the 2025 UN climate conference, also known as COP 30, which Lula hopes to hold in Belém, the capital of Pará.

In Altamira and other northern Brazilian cities, the minister of Political Coordination in the first Lula government, and later minister for Sports, then Science, Technology and Innovation, then Defense under Dilma Rousseff, lectures, takes part in debates, and gives interviews, in which he defends illegal miners and the regulation of mining in indigenous territories. He compares illegal miners to the bandeirantes (the explorers, slavers and treasure hunters of colonial-era Brazil), who he describes as “expanders” of the country’s borders, and says he is fighting to unlock the region’s development potential against a “negative agenda” of deforestation and tragedies involving Brazil’s original peoples. Aldo claims such facts monopolize the news due to the influence of NGOs representing “foreign interests”, that are in cahoots with control and inspection bodies such as Brazil’s Public Prosecutor and Ibama, the country’s environmental protection agency. He rarely criticizes Jair Bolsonaro, but does not spare his attacks on Marina Silva, Brazil’s Minister for the Environment and Climate Change, and Sonia Guajajara, the country’s Minister of Indigenous Peoples, whom he calls “agents” of the US and European governments.

The targets selected by the former minister, and the often conspiratorial tone with which he frames political disputes, move him closer to Brazil’s ruralist movements and also to the country’s military, two sectors he has courted for a long time and which he considers a vital part of the defense of Brazil’s “national interest”. Bolsonaro and General Eduardo Villas Bôas – the former military commander who paved the way for ex-army captain Bolsonaro to become president – have praised Aldo on social media. The president of the Altamira Union of Rural Producers, Maria Augusta Silva Neta, says farmers in the region established a “work proposal-based relationship” with him, which she says is unremunerated, “to change people’s vision, so they see us differently.” Edward Luz, known as the “anthropologist of the ruralists,” says he sees the former communist as “someone who can bring together sectors of the right and left” and also a future candidate for president.

Know a man by his friends

That Aldo Rebelo has become a figurehead of Altamira’s agrarian elite, many of whom are linked to land grabbing and the murder of camponeses (small-hold farmers) and their supporters, was made clear in March, when Bolsonarist senators Zequinha Marinho and Damares Alves, both from Brazil’s far right Liberal Party, flew to the city for a public meeting convened at the request of the Altamira Union of Rural Producers. The main objective of the meeting, at the city’s Convention and Courses Center, was to discuss how to block the establishment of the Ribeirinho Territory, which has been pending since 2019 and is an Ibama requirement for the renewal of the operating license for the Belo Monte hydroelectric plant. The territory will house around 300 ribeirinho (members of traditional riverside communities) families who were expelled from the banks and islands of the Xingu River when the course of the river was altered to construct the plant’s reservoir. For the territory to be established, land will need to be expropriated.

At one point, Zequinha summoned Silvério Fernandes, coordinator of the Trans-Amazon nucleus of the Pará Agriculture and Livestock Federation to the stage. Silvério, a former deputy mayor of Altamira, represents one of the most powerful families in this region in southwestern Pará, which is claiming thousands of hectares of unregistered land. In 2018, when in charge of the rural workers union in the city of Anapu, he led accusations of criminal association and invasion of property against Father José Amaro Lopes de Souza, from the prelacy of Xingu, that resulted in the priest being imprisoned for three months. Father José, whose release was finally authorized by Brazil’s Federal Supreme Court, had worked with Sister Dorothy Stang, the missionary and agrarian reform advocate murdered in 2005. At the time of the murder, Silvério’s brother Délio admitted he had been visited at his ranch by one of the men who ordered Stang’s killing, the farmer Vitalmiro Bastos de Moura, shortly after the murder.

SILVERIO FERNANDES, COORDINATOR OF THE STATE OF PARÁ’S AGRICULTURE AND CATTLE RANCHING FEDERATION’S TRANSAMAZONIAN NUCLEUS (FAEPA), ON STAGE WITH DAMARES ALVES AND ZEQUINHA MARINHO. PHOTO: RODRIGO CORREIA/SUMAÚMA

On stage, Silvério positioned himself between Zequinha and Damares. He said briefly that he did not support the establishing of the Ribeirinho Territory “without dialogue” and stated he was against the approval of Ituna Itatá and the removal of invaders from Cachoeira Seca, two indigenous territories in the region which in recent years have seen record levels of deforestation. Then, patting Damares Alves on the shoulder, he praised Aldo Rebelo, who, until 2017, had for 40 years been a militant in the communist party behind the anti-junta Araguaia Guerrilla uprising in the Amazon during the business-military dictatorship which ruled Brazil between 1964 and 1985. “I want to say in the last few months I have got to know someone who amazed me with his stance: the former government minister Aldo Rebelo,” Silvério said. “He has to be on our team, Zequinha, because he is a real Amazonian. I came to admire him despite his past with an utterly leftist party, because his thinking does not match the party he was in.”

Aldo’s presence at the meeting had initially been advertised, but due to a postponement, he could not attend. Instead, he was in the Amazonas state capital Manaus, launching a book he originally published in 2021, which contains his current political manifesto: The Fifth Movement – Proposals For An Unfinished Construction (Já Editores publishing house). However, like senators Hamilton Mourão (Republicans party), a retired general who was Bolsonaro’s vice-president, and Tereza Cristina (Progressistas), Minister of Agriculture under Bolsonaro, Aldo Rebelo sent a video message to the land grabbers and rural landowners of Altamira. He did not directly mention the Ribeirinho Territory – he told SUMAÚMA he was not aware of the project – but instead focused his wrath on NGOs.

.

“The Amazon has definitively entered the global agenda not just because of the climate, or global warming, but because of the great promise it holds for its people. It is no coincidence that hundreds of NGOs, foreign or financed from abroad, are in the Amazon, including in Altamira. They are not only there for the environment, for the protection of the Indians (a term used by Aldo rather than indigenous people), which are just and humanitarian causes, they are not only seeking to do us good, they are seeking our goods,” he said.

Aldo went on to echo the attacks of Zequinha Marinho, which cast doubts on the actions of Brazil’s Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office. “As neighbors of the climate conference to be held in the Amazon in 2025, the Senate should look out for the producers, growers and breeders of the region, who are under serious pressure, often from government agencies, often from the Public Prosecutor, which refuses to meet with rural producers, but often spends time with foreign non-governmental organizations,” he stated.

Imitating Bolsonaro’s demonization of NGOs

Aldo Rebelo’s concerns align with those of Edward Luz, who was also at the meeting in March. A consultant to rural producers and unions, the anthropologist has been arrested twice, in 2020 and 2022, for trying to prevent inspections by the Federal Police and Ibama in Ituna Itatá. Luz contests the presence of isolated indigenous people in the area, evidence of which was confirmed in 2011 by a team from Brazil’s National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples, Funai. He declares himself in favor of the demarcation of indigenous territories, but not what he calls “artificial ethnic territorialization”, which “transforms anyone who declares themselves indigenous, quilombola (residents of communities originally formed by escaped enslaved peoples), or ribeirinho into an artificial ethnic population.” Self-declaration, however, is the international norm, adopted by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics.

EDWARD LUZ, KNOWN AS ‘THE RURALIST BLOC’S ANTHROPOLOGIST’ DISCUSSES RIVERSIDE PEOPLE’S TERRITORY AT AN EVENT THAT HE WAS INVITED TO BY SENATORS (LEFT). MARIA AUGUSTA NETA, PRESIDENT OF SIRALTA (THE MUNICIPALITY OF ALTAMIRA’S RURAL UNION) IS PICTURED ON THE RIGHT. PHOTOS: RODRIGO CORREIA/SUMAÚMA

Before the meeting, Luz had posted on his social media accounts that the event would “kick off the civic campaign to open a parliamentary enquiry commission into NGOs.” Such an enquiry was proposed in 2019 by Senator Plínio Valério (Brazilian Social Democracy Party), who cited allegations of the misappropriation and “misrepresentation” of public resources, in addition to “suspicions” of irregular activities, “including in the services of foreign-based companies and in the interests of foreign powers”. The creation of the enquiry commission was authorized in April, signed off by 37 senators, all from the opposition, including Zequinha Marinho, Mourão, Tereza Cristina and Bolsonaro’s son Flávio (Liberal Party).

There have already been two such parliamentary investigations into NGOs in the Brazilian Senate, the first running from 2001 to 2002, and the second from 2007 to 2010. Yet despite attempts to criminalize NGOs – in recent years a strategy of the extreme right – the facts tell a different story. A study by Aline Gonçalves de Souza and Eduardo Pannunzio, from the Getúlio Vargas Foundation think tank, concluded in 2019 that the two commissions of enquiry found a “small number of irregularities” – ten cases in the first and seven in the second –“compared to the number of organizations and the intensity of the investigations.” The principal result of the enquiries was the approval, in 2014, of a law known as the Regulatory Framework for Civil Society Organizations, which established stricter rules for partnerships between the public sector and NGOs.

Edward Luz called Aldo Rebelo “our future candidate for president of Brazil”. “Aldo has shown sensitivity, we’ve had several conversations with him, and for me he’s someone who can bring together sectors on the right and left,” he stated. He said Bolsonaro had disappointed him in 2022 by not accepting suggestions for a major celebration to mark the 50 years of the Trans-Amazonian Highway, and when he sent the military to repress environmental crimes in the Amazon. “He thought he was going to please the Greeks and the Trojans but he didn’t do either.”

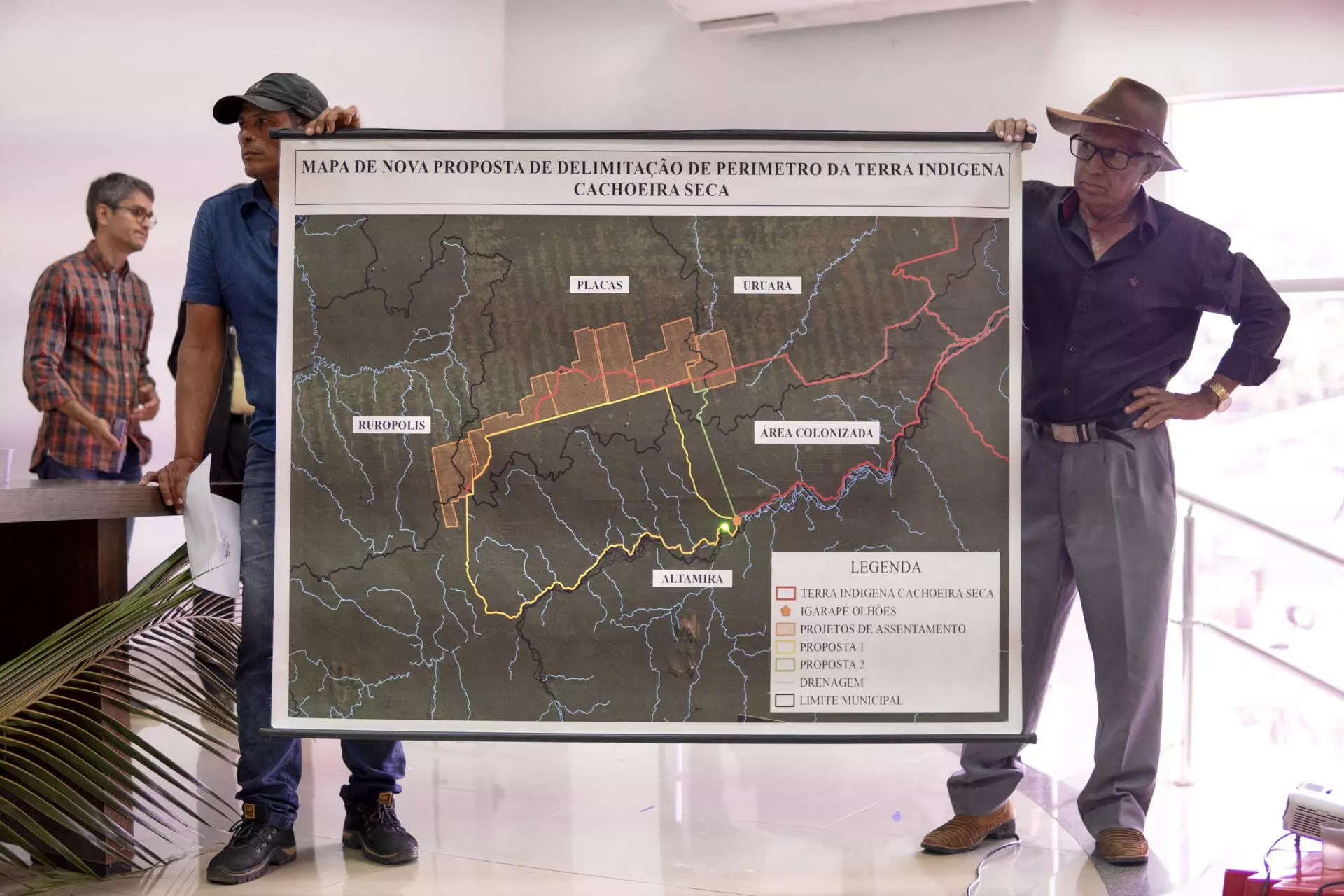

PARTICIPANTS OF THE MEETING CALLED BY SENATORS TO DEAL WITH RIVERSIDE PEOPLE’S TERRITORY EXHIBIT A MAP OF A NEW DEMARCATION PROPOSAL FOR THE CACHOEIRA SECA INDIGENOUS LAND. PHOTO: RODRIGO CORREIA/SUMAÚMA

Four days after the meeting, Aldo Rebelo was back in a hotel in Altamira, announcing he was staying for at least another month. The signs are both he and his supporters were concerned that reports announcing him as a potential candidate for Brazil’s next presidential elections, at this early stage of the electoral process, could bury his plans. Luz sent a message to SUMAÚMA, saying he wanted to clarify his position. “I and other Amazonian citizens from the north of the country admire his concern for our region. Yes, we would like to have him represent our region in an office of the Republic (of Brazil). But I must emphasize there is no confirmed political strategy or movement in this direction yet,” he wrote. “In the eagerness to see ourselves represented by someone, we have to consider how this candidate is accepted by his electorate. What we have is an admiration for his love of Brazil and his nationalism. An admiration for his vision of Brazil. Nothing more concrete or definitive than that,” he added.

Asked whether Aldo Rebelo’s candidacy for the presidency would meet with resistance, Luz said “probably, from both sides.” “Like me, Aldo is highly critical of some of Bolsonaro’s positions, which would be a potential barrier for the more Bolsonarist sectors in the region.” In an interview with SUMAÚMA, Aldo Rebelo was keen to dampen any such presidential expectations. He said he does not want to get involved in “political confusion” which would disrupt the debate on the Amazon: “I was a member of congress for São Paulo six times, I was president of Congress, I was a minister of state four times. What more do I aspire to? What role? I think my political mission is more that of a preacher than a candidate.”

He also sought to distance himself from the praise from Silvério Fernandes and Edward Luz, and downplayed his dealings with both men. “Silvério is a leader of the Pará Agriculture and Livestock Federation. I have already held meetings and lectures there, and met him,” he said. He said he “doesn’t know (Luiz) well”, but met him at a hearing in Congress “about 15 years ago”, again at a lecture in Santarém, and recently in Altamira. “But I don’t have a personal relationship with him.”

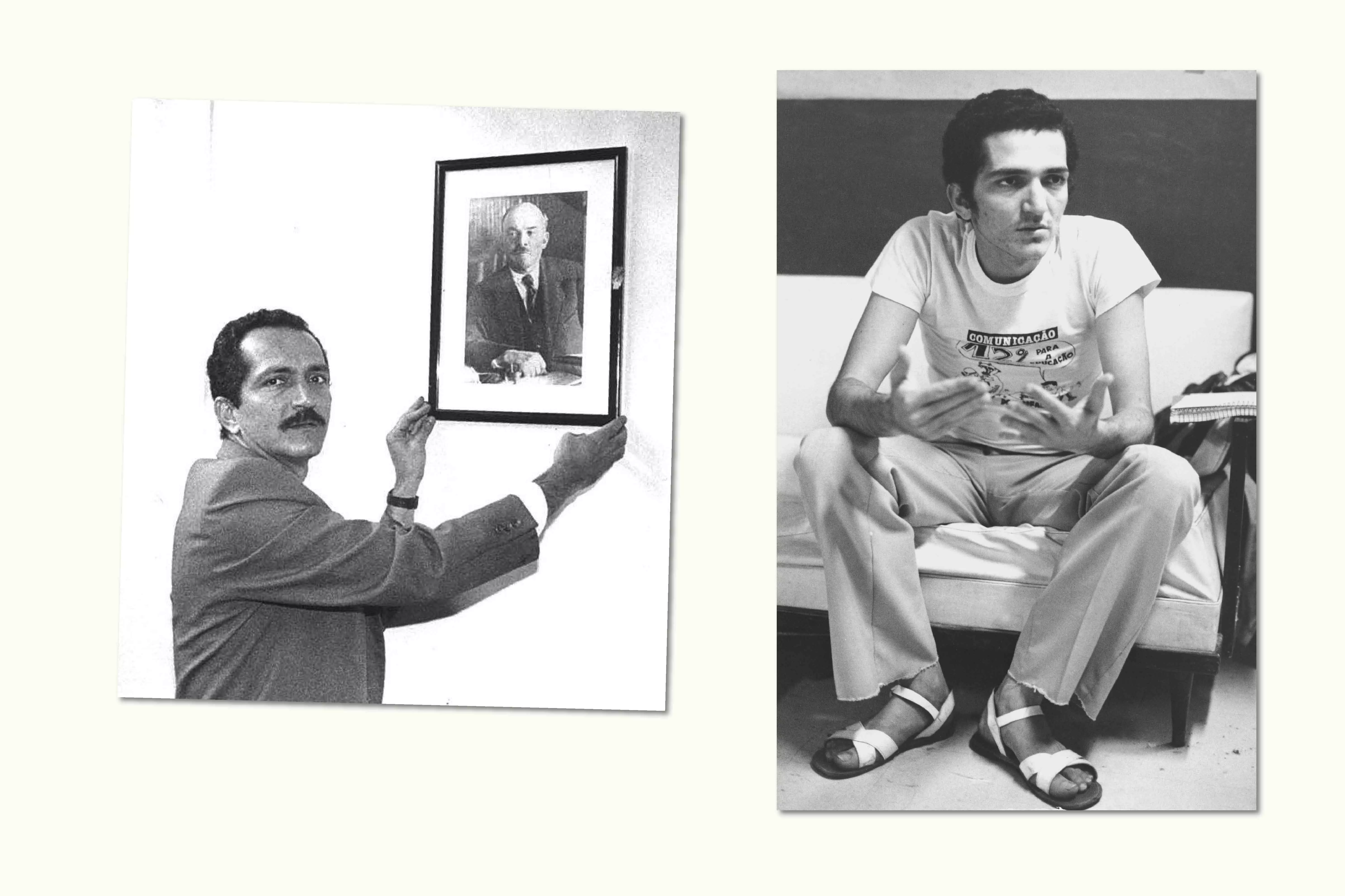

LEFT: ALDO REBELO WHEN HE WAS A FEDERAL DEPUTY FOR BRAZIL’S COMMUNIST PARTY FOR THE STATE OF SAO PAULO HOLDS A PORTRAIT OF VLADIMIR LENIN, IN BRASILIA, IN DECEMBER 1992. PHOTO: AILTON DE FREITAS/FOLHAPRESS. RIGHT: ALDO REBELO WHEN HE WAS PRESIDENT OF THE NATIONAL STUDENTS’ UNION (UNE), A POSITION HE HELD UNTIL 1981. PHOTO: ESTADÃO ARCHIVE

Aldo Rebelo announced his intention to spend a few months in Altamira at the beginning of December last year, saying he would write a new book in the city, entitled The Curse of Tordesillas. In it he plans to set out a thesis particularly well received by military leadership: “the story of international greed over the Amazon.” He intends to explain how “we inherited this region [from the Portuguese, according to him], and were not able to protect this heritage.” In addition, the book will include an inventory of the riches of the region and a “project outline” for the Amazon, in which Altamira, the largest municipal region in Brazil, is a “city-symbol”.

Political musical chairs

At the time, Aldo had just been defeated in the São Paulo state senate race, finishing seventh with 230,833 votes, 1.07% of the total, behind Vivian Mendes, from the Popular and Socialist Union Party, who beat him by almost 50,000 votes. He stood for the Democratic Labor Party, the third party he had joined after leaving the Communist Party of Brazil in 2017, due to “programmatic and political differences”, according to a statement released by the party – which had been part of the loose coalition of every Workers’ Party government since 2003 – at the time. Aldo also had a brief spell with the Brazilian Socialist Party and, in 2018, put himself forward as a presidential candidate for the Solidarity party, but soon withdrew from the race.

In the Communist Party of Brazil, founded by Leonel Brizola, Aldo was fervently welcomed by the most anti-Workers’ Party sectors, including activists from the so-called New Resistance movement – a group inspired by the ideas of Alexander Dugin, a Russian anti-enlightenment philosopher, who argues for a multipolar world in which Russia would have a role due to its ancestral civilization. The rejection of modernity and the recovery of a mythical past place Dugin’s views alongside the theories of the Bolsonarist ideologist, Olavo de Carvalho, who died in 2022. Aldo’s evocation of the founding myths of Brazilian nationality, as established at the beginning of the last century, and his professed desire to combat “imperialist advances” on the country’s wealth, explain his appeal to this group.

It is hard to know how far Aldo Rebelo’s message could reach, but it has already had repercussions in specialized agribusiness circles. Claiming to have no other professional activity today than that of a journalist, he is a columnist for the Belém-based newspaper O Liberal and the AgroMais (“More Agriculture”) channel of the Bandeirantes media network. He is heard frequently on the Canal Rural (the “Rural Channel”) – which belongs to the J&F invested group, owned by Joesley Batista, and is broadcast nationally by satellite and cable services – and on sites such as Agro em Dia (“Agriculture Today”), specializing in agribusiness and based in Brasília, and Notícias Agrícolas (“Agriculture News”), which describes itself as a portal which communicates directly with Brazil’s rural producers. He has relatively few followers on Twitter (55,900) and Instagram (11,900), and also uses the Fifth Movement and Questão Nacional (“National Question”) profiles on social media. Aldo usually gives long interviews on the internet, being a frequent guest of YouTubers who identify as “nationalists” and of Brasil Paralelo (“Parallel Brazil”), the film production company aligned with Bolsonarism that was born out of the self-styled “new right” movement that sought to overthrow Dilma Rousseff, and was accused by Brazil’s Superior Electoral Court of spreading fake news during the last election campaign.

Far right in search of new leaders

Aldo Rebelo was one of the few people with no direct connection to the Bolsonarist far right to be interviewed for the series “The Right in Brazil”, launched by Brasil Paralelo in March to discuss a new direction for the movement after Bolsonaro’s electoral defeat. In three episodes, the series ignores the influence of the military in the Bolsonaro government, praises former minister Paulo Guedes’s economic policies, and gives ample space to former judge and government minister, and current senator from Paraná, Sergio Moro, to defend himself against the illegalities of the Operation Car Wash anti-corruption investigation. The series holds Bolsonaro ultimately responsible for Lula’s victory in 2022: for his reckless bravado, his blundering children and his lack of compassion for the victims of Covid-19. It makes it clear that this is a political sector in search of new leaders.

When he appears in the series, Aldo situates himself equidistantly from Bolsonaro and Lula. “The antagonists have to respect the rules of the game, yet instead they use these rules to try to destroy each other,” he says. He told SUMAÚMA he does not intend to position himself as a third way, “because there’s already a bottleneck”, and that he does not choose to speak to the far right: “I give interviews to those who come looking for me”. He claimed he did not even know what Brasil Paralelo was – “I thought it was linked to a university” – and that he only found out when the interview was attacked by both the right and left.

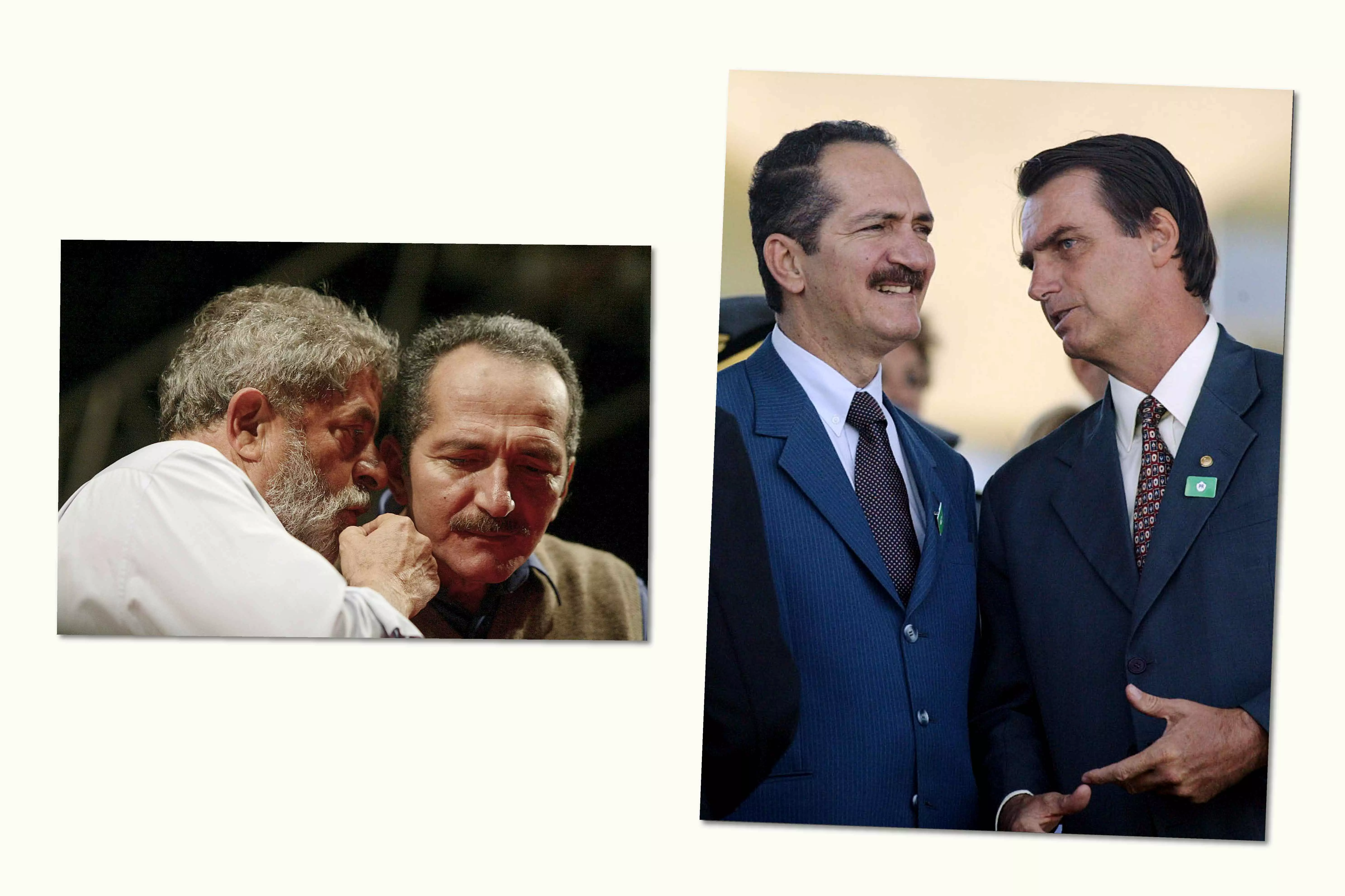

LEFT: THE THEN-PRESIDENT LULA, RUNNING FOR REELECTION, TALKING WITH ALDO REBELO, WHO AT THE TIME WAS THE PRESIDENT OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, DURING A RALLY IN THE MUNICIPALITY OF SÃO VICENTE IN THE STATE OF SAO PAULO, SEPTEMBER 2006. PHOTO: LEONARDO WEN/FOLHAPRESS. RIGHT: ALDO REBELO, WHEN HE WAS A MINISTER, TALKS WITH JAIR BOLSONARO, WHO WAS THEN A FEDERAL DEPUTY, DURING A CEREMONY TO CELEBRATE BRAZILIAN ARMY DAY, IN BRASILIA, IN APRIL 2004. PHOTO: SÉRGIO LIMA/FOLHAPRESS

Aldo, however, sometimes uses discursive codes beloved of the far right, which place Brazil in a moral and social chaos that demands a savior. One example is the video from the Fifth Movement – the name of both his book and the political project whose message he spreads online – that he shared on his social media accounts in March. To a soundtrack of “Bones”, by the American band Imagine Dragons, whose lyrics talk about losing patience, losing control and playing with a stick of dynamite, the 51-second clip mixes scenes of armed drug dealers, an attack on a teacher in school, coup plotters in Brasilia on January 8, Black Blocs, hunger and disasters. The first part ends with a drawing of a meme known as Wojak, associated with feelings of loneliness and powerlessness, and the culture of the involuntary celibacy movement that gestated in the digital forums of the ultra-right. In the final 21 seconds, there are images of Aldo himself, on horseback, passing soldiers on parade, accompanied by children, in a leather jacket and Panama hat.

Once again he tried to disassociate himself from the video: “These are young people I barely know, who are part of this debate, who produce these videos, with a language I haven’t mastered, a highly contemporary, young language, often using a musical background I know nothing about. They produce it and put it on the internet, they want to participate in the debate. Sometimes I share it when it seems like a good idea,” he said.

Critics and admirers believe that Aldo’s current positions demonstrate his intention to establish an agricultural-military bloc, two sectors now orphaned by Bolsonaro’s defeat. Journalist Luis Nassif, co-editor of the Jornal GGN newspaper, for example wrote in September 2022: “It is now clear that all of his (Aldo Rebelo’s) movements, even when part of the Dilma Rousseff government, were aimed at boycotting the government and consolidating an alliance with two segments: the ruralists and the military.” Gustavo Castañon, professor of philosophy at the Federal University of Juiz de Fora and leader of the social media shock troops of Ciro Gomes of the Democratic Labor Party, noted when reviewing Aldo’s book last year: “A union at this moment between Aldo and the Democratic Labor Party and Ciro Gomes would bring much of what Ciro lacks to be the leader that Brazil needs: a constructive union between the labor movement and the armed forces, and that on the right which still has a national interest in Brazil, agribusiness.”

When, during an interview with the 247 website (linked to the left of the Workers’ Party) in February, he was pressed for his views on the role of the military in the January attack on Brazil’s institutions – and the part agribusiness played in financing the coup leaders – Aldo Rebelo said: “I hope President Lula doesn’t listen to these advisors, that he doesn’t choose to wage war against agriculture or the military.” In the same interview, he stated that the “rabble rousers” should be punished, “exemplarily” in the case of police and military personnel who have a legal monopoly on the use of force. At no time, however, did he condemn the military leadership of the Bolsonaro government, which released a statement saying the coup-supporting crowds outside the barracks were “legitimate.”

THE THEN-MINISTER OF DEFENSE ALDO REBELO ATTENDS A PUBLIC HEARING WITH GENERAL VILLAS BOAS IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, IN 2015. PHOTO: LUCIO BERNARDO

Aldo Rebelo has a longstanding friendship with General Eduardo Villas Bôas, whose wife visited the camp where Bolsonaro supporters were protesting against the result of the presidential election outside the Brazilian Army headquarters in Brasília. Villas Bôas’s most notorious act was to pressure the Federal Supreme Court into refusing Lula the right of habeas corpus when Brazil’s current president was imprisoned in 2018, which would have allowed him to appeal his conviction at liberty – a decision that forced him from the presidential race. He was then a special advisor to Bolsonaro’s Institutional Security Office, commanded by another military man, Augusto Heleno. He and Aldo have known each other since Villas Bôas, then a colonel, was head of the army’s parliamentary advisory office in the 1990s. And when Villas Bôas commanded the army, Aldo was in charge of the Ministry of Defense. Last year, the general declared his support for his politician friend’s Senate candidacy, calling him the “only Brazilian statesman” he knew. Aldo Rebelo, meanwhile, said he understands “the value of friendship” and as a result, will not criticize Villas Bôas. “It is not a simple thing to criticize a friend. This doesn’t mean that friends don’t have flaws, that friends don’t make mistakes.”

A crusade against climate activism

Despite his relationships with the military and agribusiness, Aldo maintains he is trying to form a “much broader” union. “Its objective is, in the first place, the workers’ movement and, alongside the workers, the military, because they have a nationalist tradition in Brazil, and are important builders of our country, an institution that guards our memory, our history. And agriculture, because it is part of how Brazil was formed. When you study economic cycles, you see the presence of the fields. In Brazil, we need an alliance that involves workers, farmers, the military, the middle classes, to build a path for development with social balance, a reduction of inequalities, and democracy,” he said. Although Aldo uses the word “farmers”, many of his supporters in Altamira and the surrounding region are land grabbers and large-scale landowners, some suspected of environmental crimes and intensely antagonistic towards family farmers in rural settlements.

Since mid-January, Aldo Rebelo has been visiting universities, business organizations and agribusiness fairs throughout the Amazon region. He was at the Union of Rural Producers of Marabá; with union leaders in Belém; spoke to students from technical schools in Paragominas; gave a master class, via video, to students of the Graduate Program in Animal Science and Fishery Resources at the Amazonas Federal University; and attended the National Opening of the Soybean Harvest, in Santarém. In early March, he was the target of a protest by indigenous students at South and Southeastern Pará Federal University, in Marabá, a city on the route of the Trans-Amazonian Highway. His declarations make the news in the local and specialized press, such as when he told soybean farmers that “Brazil producing grain in the Amazon bothers countries that have already deforested their territories.”

In February, Aldo told the YouTube channel Politizando (“Politicizing”), led by William Jacob, former congressional candidate for the Democratic Labor Party in the state of Minas Gerais, that he wants to prevent the scheduled 2025 climate conference in Belém from becoming a meeting of “guardians of the forest”. “Nobody talks about the 26 million abandoned Brazilians in the Amazon. Will the 600,000 people studying at universities in the Amazon become guardians of the forest, will they graduate in gas and oil to hug chestnut or rubber trees?” He said he “stimulates” local organization around four points, which are the same as the “project for the Amazon” that he will set out in his book: “sovereignty”; “the right to development”; “removing indigenous people from the tutelage of NGOs and providing them with essential services”; and “caring for the environment.”

In the same interview, Aldo criticized ministers Marina and Sonia Guajajara, to whom he gives special prominence in his conspiratorial vision. “Marina [Silva] is a contracted minister at the service of the US agenda. The Amazon region [under Lula’s government] is very close to a national betrayal. Marina with her team, and Guajajara, are from there, they’re more from the Democratic Party than from the Brazilian government. The Minister of Human Rights [Silvio Almeida, who is Black, is one of the most respected legal specialists in Brazil] is also from there,” he said.

The violence of the attack echoes Bolsonaro’s statements against the organizations that denounced deforestation in the Amazon and the dismantling of policies to protect indigenous peoples – “I can’t kill this cancer there is in the Amazon called NGOs,” said the then president in 2020. Questioned about his virulence, Aldo turned on Lula: he said the two ministers were appointed due to an alleged “commitment” between the president and “environmentalist sectors” from European countries such as France and Norway and Joe Biden’s Democrat party, made during Lula’s election campaign.

The stories in Aldo’s speeches are often repeated, such as that of the four-day visit of King Harald V of Norway to a Yanomami village, at the invitation of shaman and leader Davi Kopenawa, in 2013. At the king’s request, news of the visit was only released after its conclusion, but Itamaraty (Brazil’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs), Funai and the Federal Police were informed in advance. Aldo gives the episode an air of conspiracy when describing it, emulating General Villas Bôas, who in 2017, in an interview with TV Globo’s Conversations with Bial program, said that the king’s visit showed a “failure in Brazilian sovereignty” over the Amazon.

ALDO REBELO, WHEN HE WAS A FEDERAL DEPUTY FOR BRAZIL’S COMMUNIST PARTY FOR THE STATE OF SAO PAULO, TAKES PART IN 2011 IN A RALLY ORGANIZED BY THE STATE OF MATO GROSSO’S RURALIST BLOC IN DEFENSE OF THE PROPOSAL TO CHANGE THE FOREST CODE, OF WHICH HE WAS THE RAPPORTEUR. THE TEXT WAS CHALLENGED BY ENVIRONMENTALISTS. PHOTO: LUIZ ALVES/CÂMARA DOS DEPUTIES

To reinforce his argument, Rebelo usually cites the book Environmentalism, Imperialism and NGOs in the Amazon, by Nazira Camely, a professor at Fluminense Federal University, in Niterói. “The professor demonstrates in her doctoral thesis that this National System of Conservation Units is copied from the United States Agency for International Development,” he said.

The book is the result of field research in the Chico Mendes Extractive Reserve and the Serra do Divisor National Park, both in Acre, the state where Camely – a geographer and economist who defines herself as a Marxist – was born. She has a highly critical view of the work of foreign environmental NGOs and their association with Brazilian organizations, because, as she told SUMAÚMA, “for us to delegate the management of our territory to non-governmental organizations, whether a good or bad NGO, is extremely problematic.”

The professor, whose arguments contradict Aldo’s in many ways, is angered by the appropriation of her book “by the extreme right, which has an anti-scientific view of the process, a conspiracy theory view.” Camely is against mining “in all its forms, even so-called sustainable methods,” and claims the most important national issue continues to be, after more than five centuries, the concentration of land ownership. “Brazil is a country dominated by vast landholdings, just look at Congress. The devastator of the Amazon is not little farmers. It’s the big cattle ranching estates,” she says.

Illegal miners, the new bandeirantes

After he arrived in Altamira, the first of Aldo’s statements to gain national attention involved a defense of mining. At the time, in late January, SUMAÚMA had just revealed that at least 570 Yanomami children under the age of five had died from preventable causes during the four years of the Bolsonaro government. In a lecture in the city, promoted by three entities linked to land grabbers and large scale landowners, the former minister said the tragedy of the Yanomami people “is nothing new” and complained that the illegal prospectors were being treated like “the scum of the earth”. Days after the lecture, Bolsonaro – who facilitated the entry of mining into the indigenous territory – shared on Twitter a video posted on TikTok in which Aldo said that the illegal miners were the actual indigenous people “who live in the reserves”, and not those “who live in France or Italy.”

In his statements in defense of the miners, Aldo describes them as the “new bandeirantes.” “Prospectors have historically defined Brazil’s borders, breaking the limits of Tordesillas (…) The prospector represents the de facto occupation of Brazil, which is why he is the target of a sordid and criminal campaign. Criminals should be punished, but demonizing the prospector is something else,” he told the Politizando channel. He argues for the application of articles 231, 174 and 176 of the Brazilian Constitution, which deal, respectively, with the rights of indigenous peoples and the possibility of mining on their lands; the organization of miners into cooperatives; and the state’s concession of mining and hydraulic energy exploitation rights.

However, although article 174 states that the government must allow the organization of miners into cooperatives, it does not apply to lands belonging to native peoples, explains lawyer Juliana de Paula Batista, from Brazil’s Socioenvironmental Institute. “According to the Constitution, the exploitation of mineral and water resources in indigenous territories is subject to regulation, but mining is not regulated, because article 231, paragraph 7, excludes the entire mining system of laws from indigenous territories. It categorically says the mining laws do not apply there,” she said.

Nostalgia for the myth of racial democracy

The break between the Aldo Rebelo of today and the politician of old is not entirely clean. When he was still in the Communist Party of Brazil, Aldo became known for a form of nationalism that emphasized a kind of “benign synthesis” of the groups that had conquered and populated the territory of Brazil. He wanted to regulate the use of “foreign expressions” in Portuguese, and even proposed a law on the subject that was ultimately rejected in the Senate. Born in Viçosa, Alagoas, he authored the law that made November 20, 1995, the 300th anniversary of the death of Zumbi (the Brazilian quilombola leader and pioneer of resistance to slavery), a commemorative day. Another law, proposed by then Senator Serys Slhessarenko and approved in 2011, made National Zumbi and Black Awareness Day a holiday across Brazil.

Now, when he is asked why he left the Communist Party of Brazil and distanced himself from the left, he says it was because of “identitarianism”, a controversial term used by both the right and left to caricature movements that advocate for greater equality and representation for historically discriminated against groups. The left “disorientates” when it “replaces the centrality of the national question with questions of race and gender,” Aldo told Brasil Paralelo. In doing so, he added, “it subtracts energies” from the principal conflict, which is “between imperial and emerging nations, which seek economic and technological emancipation.”

AS PART OF A “CULTURE WAR,” REBELO HAS BECOME A FIXTURE IN THE RIGHT-WING MEDIA AND ON AGRICULTURAL PROGRAMS. THE FORMER CONGRESSMAN HAS PRODUCED CONTENT FOR PRODUCTION COMPANIES LINKED TO RIGHT-WING GROUPS, SUCH AS BRASIL PARALELO (PHOTO ON THE LEFT)

Not that such discussions are exclusive to Brazil. There is a sector on the left for which the role of movements of women, Black people, indigenous peoples and LGBTQIA+ communities diverts focus from combating the evils of capitalism. On the extreme right, the subject is explored through the so-called “culture wars”, from the perspective of religion and customs, and adopts the form of a power dispute: it is argued there is a supposed wish to replace the heterosexual, Christian white man with people of other skin colors, genders and religions. “What happens is that the left has given the impression that it doesn’t defend the family, religion, or national values. We know this isn’t true, but when sectors of the left attack these ideas, and the left remains silent, it legitimizes the attacks of the conservative sector and the right,” argued Aldo.

Aldo has often claimed there is a “hybrid war” against Brazil. He has said it is “difficult to locate” who is conducting it, but almost always points to the US and European countries, without mentioning the associations between the Brazilian and global extreme right. He sees a continuity of the aim of “making Brazil fragile” that runs from the 2013 protests against Dilma Rousseff to Bolsonaro. “I think [the 2013 movement] would have happened to any government, because Brazil was a threat to the global geopolitical balance and had to be contained. And this hybrid war continued even during part of the Bolsonaro government. I saw the pressure the US and the EU exerted on the government at certain times, when it decided to visit Russia on account of an agreement for agricultural supplies,” he said.

The entire basis for the recent positions of Aldo Rebelo – and even the stories he tells – is contained in The Fifth Movement. The 234-page book fails to offer a pathway to what this new fifth stage in Brazil’s history might be like, but the chronology of the four previous movements provides clues to the former minister’s thinking. The first is the “formation of the physical base” of Brazil; the second is the country’s independence; the third is the “consolidation of independence and territorial unity”; and the fourth is the “Republic and the Vargas Era, Deodoro, Floriano and the Revolution of 1930.” The years of the Getúlio Vargas government – which included the Estado Novo dictatorship, which saw widespread persecution of opponents and rampant nationalism – are described as “the most creative and transformative in the history” of Brazil. The 1988 Constitution, which enshrined social and political rights, inaugurating the so-called “New Republic”, is ignored.

In the book, which is reminiscent of the morals and civics classes of the dictatorship era, Aldo Rebelo speaks out against “left- and right-wing cosmopolitanism” and the division of the “nation along racial lines.” He exalts miscegenation without mentioning the racial quotas that changed the face of Brazil’s universities – he told SUMAÚMA that he is not against such a policy, as long as those from mixed ethnic backgrounds are not excluded “in the distribution” of places, and that value is given to social quotas for poorer Brazilians. In his book, he laments that “hierarchy and discipline” have been “swept away” from schools and defends a curricular reform that brings a “critical but optimistic interpretation of Brazilian social formation.” He also proposes “motherhood appreciation campaigns”, since “every woman should be able to exercise this sacred right.”

In The Fifth Movement, the indigenous Brazilians who allied with the Portuguese are praised, and the bandeirantes occupy a place of honor for having broken through the limits of the Treaty of Tordesillas, “one of the greatest achievements in the history of mankind, with the size of the incorporated territory being bigger than Western Europe today.” The bandeirantes, he says, were “a joint venture of settlers and natives”, as “penetration into the territory united the indigenous peoples knowledge of geography and Portuguese technology.” An admirer of José Bonifácio – he is also part of an institute named after the “patriarch of Independence” – the former minister highlights the role of the military against republican or separatist regional revolts in the 19th century, and says they are “above regionalisms and are bearers of the national consciousness.”

Agribusiness, in Aldo’s view, is the target of “defamation orchestrated by the agents” of its international competitors. Such an analysis ignores the fact that the political strategy of the agribusiness sectors, highly influential in the Brazilian Congress, is closely related to transnational corporations. “Once the logistical bottlenecks and sabotage on the pretext of environmental issues are overcome, Brazil will be the only country in the world to possess the complete future high-tech food industry chain.” Although he says environmental crimes must be punished, he regrets the extent to which such crimes are publicized: “Our schools feed false news and reinforce defamations against agriculture, livestock and the Amazon,” he writes. The former deputy was the rapporteur for the new Forestry Code approved in 2012. At the time he shifted closer to the ruralists in Congress and was criticized by environmentalists for providing an amnesty to deforestation that had occurred before the law was enacted.

In The Fifth Movement, Aldo declares himself against “neo-Malthusian environmentalism” – which, according to him, would expel the population from the Amazon, in what he also calls “detropicalizing” the region. His message resonated deeply among land grabbers and landowners in Altamira. “We can no longer take these people out of here. We need to clarify how we should produce in the Amazon, and make the most of those who are doing it right, but when the inspections come, they throw everyone in the same basket,” said Maria Augusta, the president of the local rural workers union.

She calls for a “task force” for land and environmental regularization in the Amazon, and Aldo Rebelo agrees this is the “big challenge” for the region. “I think there is an obstacle in the structure of the state, which has neither the means or the people, and there are also sectors that don’t want such regularization because it consolidates the economic activity of the area, the presence (of people), agriculture, livestock, extractivism,” he said, suggesting, once again, a conspiracy.

There is a reality deficit in such complaints. The Bolsonaro government, which many Altamira landowners supported and which Aldo Rebelo declines to criticize, disrupted and reduced funding for the entire land regularization system in the Amazon. The number of land registration titles directly granted by the federal government went from 9,819 at its peak in 2014, to just one in 2019 and 753 in 2021, according to a study by the Amazon Institute of People and the Environment published last year.

Panama hat perched on his head, Aldo Rebelo records his thoughts for Canal Rural and his videos on the Altamira riverbank, with the Belo Monte reservoir behind him. Despite the cautious denials of an experienced politician, he has already been recognized as someone who could represent a far right disgusted with Bolsonaro in the next presidential elections. Lula’s narrow victory and the immense difficulties of a polarized Brazil have started the electoral race early. Aldo has realized the Amazon is the center of the world, and as a champion of Brazil, has initiated an agricultural-military ideological campaign that claims not to be electoral. “If people support or sympathize with the ideas, proposals or things that I argue for, that’s a choice for the people,” he says, on the subject of the expectations of his supporters. Aldo wants to be popular, but for the time being he would prefer his crusade be restricted to the local news.

Spell check (Portuguese): Elvira Gago

Translation into Spanish: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: James Young

Photography editing: Marcelo Aguilar, Mariana Greif and Pablo Albarenga