When Beatriz Matos sets foot in Javari Valley on Monday, February 27, she will be interweaving various strands of her life. It was there starting in 2004 that she fell in love with the Amazon Forest, it was there that she fell under the spell of the frontier where a number of indigenous worlds meet and talk, it was there that she met Bruno Pereira and both were seized by an “overwhelming” love, it was there that they built a house and where they dreamed of living with two children named after indigenous people. And it was there, in June last year, that Bruno was murdered, dismembered and burned while on an expedition together with British journalist Dom Philips. It is a lot to deal with. And Beatriz doesn’t know how she will cope with all of this, because since these awful events occurred, she has tried to take things one day at a time. However, Beatriz does know what she will do there. And this, in her words, fills her with “excitement and hope”.

In an action coordinated by the influential Univaja (Union of Indigenous Peoples of Javari Valley), a committee headed by Sonia Guajajara, Minister of Indigenous Peoples, will visit the region, in the State of Amazonas, to proclaim, with her presence and her actions, that the State is back. During Jair Bolsonaro’s government, Javari Valley, which borders Peru and Colombia, was effectively abandoned to drug and fish trafficking, timber theft and illegal mining. When he was executed, Bruno Pereira, one of the most important indigenous experts of his generation, was on furlough from Funai (now the National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples) because the agency was dominated by appointees whose policies ran contrary to the interests of indigenous people and nature. Bruno had been relieved of his position as coordinator of uncontacted peoples after carrying out an operation against illegal gold mining. Dom was there in order to do research for a book that already had a title: “How to save the Amazon: Ask the People Who Know”.

Today Rubén Dario da Silva Villar, known as “Colombia”, is in prison as the person who gave the order for the killings. Also in prison are Amarildo da Costa Oliveira, known as “Pelado”, his brother Oseney, and Jefferson da Silva Lima, suspected of carrying out the murders. But the crime is nowhere near being fully resolved, in terms of all its connections, and the people of Javari Valley continue to suffer under the domination of criminals, who have become used to acting with impunity over the last four years.

The state’s presence is a demonstration of force and commitment in the face of an immense challenge. For Beatriz, an anthropologist with 20 years’ experience with indigenous people and a professor at the Federal University of Pará, it also means stepping foot in the territory that is home to the largest number of uncontacted peoples on the planet. This time round, she visits as the newly appointed director of the Department of Territorial Protection and of Uncontacted and Recently Contacted Peoples at the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples. That a cultural treasure of this magnitude is under such a great threat is an indictment of the willful neglect of the Bolsonaro government, whose genocide of the Yanomami is sadly only the first horror revealed.

The following interview took place via an online videocall last Friday – with me in Altamira and Beatriz in Belém. She was getting ready to move to Brasília with her sons Pedro Uáqui, 4, and Luis Vissá, 3. When talking about Bruno, she alternated tenses: sometimes in the past, sometimes in the present. For Bia, as she is better known, Bruno was, often still is a presence in herself and in her children. Certainly his legacy will last forever in the Amazon. In this interview she talks about her fascination with Javari Valley, her deep relationship with Bruno and her plans for her new position. And also, what it meant to have her partner murdered in a country presided over by a brute like Jair Bolsonaro.

Bia is still in mourning, and it could not be any other way. But there is something about her that catches the eye even via a computer screen: she is a very lively woman whose eyes frequently flash and whose voice alternates between different nuances. All this charisma will be essential for what awaits her in Brasilia.

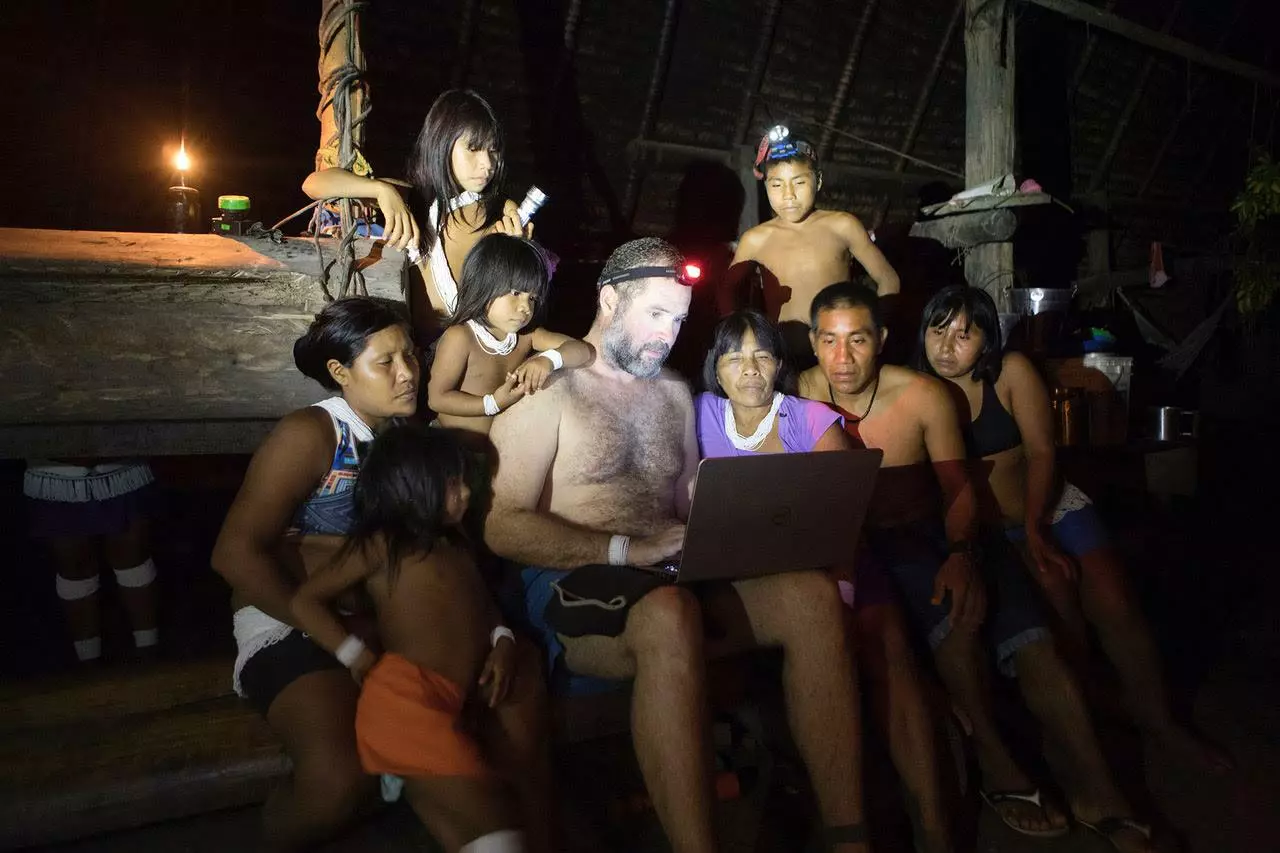

Beatriz entre indígenas Matsés da aldeia Nova Esperança, no Vale do Javari, durante pesquisa de campo para seu doutorado, em 2011. Foto: arquivo pessoal

SUMAÚMA: What is going to happen this Monday in Javari Valley?

Beatriz Matos: There is going to be an event that is being coordinated by Unijava (Union of Indigenous Peoples of Javari Valley) and by the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples to proclaim the taking back by the State of its role. It is a signal to the indigenous people and to the region, that the State will be present and that the institutions need to be respected, that we are committed to reviving the protection of the Javari Valley. Univaja will also deliver a boat that will be the mobile health unit delivered to the Korubo people, who have only recently been contacted. They used to get medical treatment at the base, but now this team will remain on this mobile health unit. This was one of Bruno’s and Lucas Albertoni’s [a doctor who specializes in indigenous health] projects. They were the ones who drew up the project and designed the boat. Bruno visited the municipality of Santarém a number of times to accompany the boat’s construction. Univaja will deliver this boat to Sesai [Special Office of Indigenous Health]. It is one more achievement in terms of the endeavors made by Bruno as well as other people. It will be a really beautiful moment. But that’s what it is, it’s an action to affirm that the State is now present. We need to confront this situation of organized crime that is taking over indigenous lands, not just in Javari Valley, but throughout the entire country. It needs to be an inter-ministerial action, because we are fighting international trafficking.

And how is this going to be done?

Going up against organized crime is a very complex thing, and you need specialists to tackle the problem. It is crazy, because it involves the same [criminal] network you find in Rio de Janeiro, in São Paulo, where it also causes the death of young black men. It is an extremely complex thing. But what we can guarantee is that the State’s security forces will protect people. To guarantee that they can act respecting the diversity of ways of life that exist there. If the profit from [drug] trafficking is a lot higher [than the communities’ traditional activities], there needs to be more repression so that the risk becomes much higher. You need to decrease the risk-benefit equation. The risk [of breaking the law] has to be higher than the profit [gained from crime].

What is it like for you to go back to Javari Valley?

I don’t know… I have not been back at all. It will be a quick trip, because I can’t stay more than a day away from the boys. And also because of my safety. I was working in Javari Valley since November, 2004. I know the region very well, I know indigenous people from various tribes, I taught classes, I carried out projects, and I am sure that a lot of people want to talk to me, to pay their respects. It is a place that I love, that I adore, where I made virtually my entire career, it was there that I met Bruno, the father of my children, I think that a big part of the reason why we fell in love was we were driven by a common passion [for Javari Valley]. We had this fantasy of living there with the boys. We had this dream, we’ve got a house there. So, there will be a lot of mixed feelings. And there is this element of justice, of reparation. Alessandra (Alessandra Sampaio – Dom Phillips’ widow) is also going.

Beatriz e Alessandra Sampaio, viúva de Dom Phillips, no ato interreligioso realizado na Catedral da Sé, em São Paulo, no dia 16 de julho de 2022. Foto: Sérgio Silva

How is all of this making you feel inside?

So many things. Do I tell the boys that I am going to Javari Valley? Because they know that their father died there, that he never came back. They are very well aware of this. They both got to know Javari Valley when I was pregnant with them. And it will also be the first action that I am going to be taking in my new position. Since this happened, I have been taking it one day at a time. I am trying just to think about the bag I am packing, what I need to leave, what I need to take out of the fridge. But actually, I am feeling anxious.

When Bruno and Dom were murdered, the Javari Valley dominated the news and became a name that is carved into people’s imagination. But people can’t get an image of the Javari Valley. Tell us about the Javari Valley that you know, and why you chose this region, out of so many Amazon regions?

It is hard to explain, because I had just graduated in 2003 and I passed the selection process for the Indigenous Work Center. I was supposed to be working somewhere else, but I looked at the map and decided I wanted to go to Javari Valley. I remember it very clearly, looking at the map and wanting to go there. I saw the river and wanted to go to that frontier.

What is a frontier for you, apart from the obvious?

A frontier is a place that concentrates an enormous diversity in a small amount of space. Diversity in terms of people, food, music, religious beliefs, ways of life, possibilities, ways of being. There are millions of ways of taking ayahuasca, there are millions of evangelical cults, millions of messianic churches, millions of movements, millions of languages. This dialog is fascinating. Leticia and Tabatinga are both very interesting towns. In Leticia you have indigenous people from Colombia, indigenous people from Peru and indigenous people from Brazil. It is a very cosmopolitan universe. In Atalaia [do Norte], even in that little place in the middle of nowhere in the Brazilian Amazon region, you have international cuisine. You can eat wonderful ceviche, drink a beer from Cusco, Peru. And all that music…. And that is Javari, too. It is very rich [in terms of diversity], with so many different peoples. One thing that impressed me is that you could spend a month without repeating the same kind of meat or fish, you know? It’s crazy, because it’s a place that I love so much and that will be marked forever by everything that happened. At the same time, it is so crazy that he died there. The right thing would have been for Bruno to die an old man, on the little floating home he said we would have, but he died like that. If he were alive, he would still be able to accomplish so much. I can imagine him when he, I don’t know, got to 60 or 70, how many things he would have done, you know what I mean? A loss like that…

Bruno Pereira, em 2018, durante seu trabalho de campo no Vale do Javari. Foto: © Gary Calton 2018

What would be justice for Bruno and Dom, justice for Javari Valley?

The people who did this need to be punished in the sense of the law, under the law. Because it is very cruel to rip someone’s life from them, to rip them out of our lives. It is very cruel to rip a father from two small children and a daughter who is now a teenager, to make him miss out on our story, to deprive us of him. It is very cruel, you know. Nobody deserves this and nobody has the right to do this to anybody. It is a really terrible thing. So, justice needs to be done. It is very important that the people who ordered the killings are punished. But the most important thing is that it doesn’t happen again. People need to be safe to walk there, to be able to live in that wonderful place without fear, to be safe to do their jobs without having their lives threatened. To be able to live their own way, in the way they want to live, without being threatened or forced to join criminal networks, without being forced to become gunmen. So, I think that the best way for justice to be done is to ensure people can live according to their way of life. Because we always have to remember that the indigenous people have been there much longer than we have.

Do you hold Bolsonaro responsible for what happened?

I hold both Bolsonaro and [Marcelo] Xavier [president of Brazil’s National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples (Funai) at the time of Bruno and Dom’s murder] responsible. Bolsonaro said that they shouldn’t be in the Javari Valley because there you have to go around with an armed escort. [“In that region, generally, you go around with an escort, they went on an adventure, we fear that the worst has happened,” said the then-president, on June 9, 2022]. I will never forget that. How can the president of a country say that about any territory that is under his jurisdiction? If it is a place where you need to go around with an armed escort, then if you are the president, you need to intervene using the Army, the Federal Police, the National Public Security Force. It is not another country, it is the country of which he was the president. [Javari Valley] became like this because the criminals were given free rein to take over. But it’s a place that has a school, has families, has children, that river is an avenue where boats go past, it is an avenue. When Bolsonaro said that, I felt like a mother who lives in Rocinha (Brazil’s largest favela in the city of Rio de Janeiro) listening to someone on TV saying this place is dangerous, that it is a place full of criminals. What an outrage, right? They are talking about where I live with my family, my son, where my children go to school, my mother uses the hospital. How is it that there is someone, an authority, declaring without even the slightest bit of shame that it is a dangerous place, that people shouldn’t live there, if the person has lived there for 40 years, right? That’s what I felt like when he said that. I have gone past that place [where Bruno and Dom were killed] more than 100 times as part of my work. By boat, in the morning, in the afternoon, at night. But they let things get to that point because of negligence, because Bolsonaro’s administration didn’t do the basic things. It is the same thing that we are now seeing with the Yanomami, his negligence is becoming clear to the whole world.

Beatriz Matos durante o trabalho com os povos Matis e Korubo, no Vale do Javari, em 2015. FOTO: ARQUIVO PESSOAL

Living through what you experienced is terrible under any circumstances, but I believe it must cause additional suffering when the country’s highest authority makes statements like this. How did each of Bolsonaro’s brutal phrases along with those made by [Hamilton] Mourão [then Brazil’s vice president] and [Marcelo] Xavier affect you?

It was the same as it must have been for the relatives of those who died of covid-19 and had to watch Bolsonaro making jokes, mimicking someone who couldn’t breathe on TV. It is unbelievable that somebody would do that. Right up until the day the bodies were discovered, I really still believed that Bruno would show up. I thought: “Bruno is so strong, because Bruno was almost two meters tall, he was a really big guy, you know? And I thought that Bruno was alive, he had just missed the boat and was waiting for someone to come by, as had happened before. That was when the clothes and the backpack appeared, you know? Then the criminals showed where they had buried them. That was when I really fell apart. And that day there was a Bolsonaro motorcycle rally here in Belém. There were firecrackers and Bolsonaro parties in the street. It was like a nightmare. You know, you would think that anyone, no matter how stupid, ignorant and ridiculous they were, would at least pretend to be moved. At least say they were sorry, you know. And the guy went and held a motorcycle rally. When it all happened, I literally went 10 days without sleep. I would sleep for an hour and wake up. And then he [Bolsonaro] said something even worse, he said that the rivers there are full of piranhas and at that time… [“By all indications, if they killed the two – I hope not – their bodies are in the water. And there won’t be much left in the water, the fish will eat them. I don’t know if there are piranhas in Javari River…”, said Bolsonaro on June 13, 2022]”. He said it like that, you know? Because I know there are bad people in this world, but at this level… How did we get to the point where we elected someone like that as president? When we had the first round [of the 2022 presidential election], and I saw the number of votes he got, I had a crying fit.

And in the second round?

To be at least partly free of that, for me it’s really another world. And, in my case and the case of my family, [if Bolsonaro won] I don’t know what would have become of us. I don’t know what would have become of the Javari Valley, what would have become of the indigenous people, what would have become of public universities.

Are you going to sue Bolsonaro?

I will analyze this calmly. I want to, but I need to assess the personal cost of this. I have two little boys. If it were just me…

Em 2015, a pedido da Funai, Beatriz fez um diagnóstico de compartilhamento de território entre os povos Matis e Korubo no Vale do Javari. Foto: arquivo pessoal

You are moving to Brasilia to take charge of the department at the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples that deals with uncontacted and recently contacted peoples. You will inhabit another ecosystem that also has its dangers, within a government that was elected with a broad front which includes a number of notorious enemies of the Amazon region, of the various biomes and of the indigenous peoples. What preparations are you making for these internal clashes?

This reminds me of a scene from Mission [a 1986 film by Roland Joffé, which is set during a foray by Jesuit priests into the Brazilian Amazon]. A character says that by comparison with the beasts of the Vatican or the court, this forest is not a big problem, you know? It’s a bit like that. But I am trying to talk to people who have already had experience in government. And I also know that I am not alone. There is a group of people who are not even in the government, but who have been activists with me for a long time, and I get advice from these people. And I am also confident of my ability to talk, you know, because sometimes it is just a matter of people getting to know each other in order to change their stance. I am a teacher and I believe very strongly in education. It is a very big opportunity and we have to work to strengthen the ministry and the minister so she is in a strong position for the disputes to come, so she has the strength to go up to a senator and say: “not this”. I have the impression that the reaction has yet to come and it will be substantial, but I am also hopeful on account of the spotlight that Lula put on the Yanomami issue, because, by going to Boa Vista, he shielded himself. It was as if he were saying: “We are talking about genocide, we are talking about a calamity, so no matter how much it costs, it will be done. A broad front, ok, but there is a limit.

When I got in contact with you for this interview and mentioned how hard it must be to make this move to Brasilia, after everything that has happened and with two small children, you remarked that, yes, it was hard to do it alone, but you were excited and hopeful. Why?

Just the fact that Bolsonaro was not reelected already gives us a lot of hope, you know? But, apart from this, I think that this government really has a different stance in relation to the indigenous issue. A clear sign of this can be seen by the creation of this ministry of indigenous peoples, which is something really historic, unprecedented in Brazil, and provides great political clout. We now have a minister, a woman, an indigenous person, someone whose metal was forged in the trenches, a person who now has the status of minister, who holds this position vis-à-vis the other authorities within the government itself. This is already an absolutely huge difference. Beforehand we were working at the Observatory for the Human Rights of Uncontacted and Recently-Contacted Peoples so that the policy would not be totally destroyed. Now, everything we have been talking and dreaming about we can actually do. Not just reconstruction, but also construction of a new policy for uncontacted and recently contacted peoples.

Your appointment to handle isolated cases is also very symbolic, in terms of your personal life. Because Bruno had a similar position at Funai, [the general coordinator of uncontacted and recently contacted peoples], from where he was pulled out by the Bolsonaro government under pressure from the ruralist bloc. And now, after everything, Lula and the Workers Party come back and you take up this position. How does this feel to you?

The uncontacted peoples’ agenda was always one of Bruno’s priorities. He joined Funai in 2010 and was already moving towards working on this issue. In ten years he became one of the country’s most important indigenous experts. We created the Observatory for the Human Rights of Uncontacted and Recently-Contacted Peoples, together with other people, first as a support network, and then officially as an organization. Bruno was on the front lines, in the field, and together with him I was thinking about [the actions and concepts]. We have a four-year old son and a three-year old as well, so, with the pregnancies, I have been very busy with this whole motherhood routine for about five years, but I never stopped working or thinking about things with him. I carried on teaching and doing research. This group of people coordinated by him to contemplate policies for the uncontacted peoples was involved in the transition of government and we helped to design this part of the new ministry. For me it was an invitation I couldn’t turn down. It is very interesting to be part of this historical moment, this opportunity to do the things we have thought about together.

Na confluência dos rios Ituí e Itacoaí fica uma entrada para a Terra Indígena Vale do Javari, no Amazonas, e uma base da Funai. Foto: Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

And what are those things?

We have plans to restructure a large part of the bases, including the physical part of the structures that enable the Funai teams to work in the field, plans to do programs in line with the specific characteristics of each territory or region where there are uncontacted populations, programs capable of working in a distinct way with each group of people, agreed upon with indigenous leaders and employees. It is also necessary to complete the identification studies. There are a number of references of uncontacted groups that are still being studied or are merely information that we need to confirm. In some regions it is necessary to go from use restriction, which is just an initial phase, to demarcation. It is also necessary to do the disintrusion [removal of invaders]. We also have urgent situations in certain areas. Right now, there is the emergency situation of the Yanomami, where there are also uncontacted people and we know illegal mining is taking place close to them. There is Javari Valley itself, there is Arariboia, there is Ituna-Itatá, and there are other regions in the north of the State of Pará. All these areas found themselves in a situation of emergency during the Bolsonaro government. So, it is risky to list one area as being more of a priority than others, because we are on the verge of genocide in a number of places.

This concept of uncontacted peoples is very fuzzy for most Brazilians. How would you explain this to people?

Summing things up in a few words is always difficult. Even more so because I am an anthropologist and a teacher… It is difficult to boil it down. In fact, this word “isolation” leads us to picture a situation that doesn’t really exist, which would be that of a people who have no relations whatsoever with other people, living just among themselves. But this is a rather false image, because when we speak of an uncontacted people we are speaking not just in relation to Brazilian society, but also in relation to that society’s organizations and institutions. The ones that we call “uncontacted peoples” often have sporadic relations with indigenous people from other nearby peoples, they may even have historical relations with riverside dwellers, with other non-indigenous people, or they have already had commercial exchanges and other relations throughout history. The isolation, in this case, is a refusal to establish lasting or constant relationships with Brazilian society. They have their own relationships and networks, their own organizations, which can take countless forms. They have their ritual relations, their exchange relations, their commercial relations, their shamanistic religious relations, and they also have relations with many more non-human peoples, with the wild boar people and with the jaguar people, for example. They may have a myriad of social relationships that go beyond human relationships. Historically, non-indigenous people come in and want to establish relationships that make these peoples part of our social organization. But the uncontacted people refuse this and demonstrate their refusal in a number of ways. Before the 1988 Constitution there was a policy of “integration”, where contact was forced on the indigenous peoples. You would give things to the indigenous people, you would talk to them, teach them Portuguese, and then you would transform and limit the social relations of that people. Or else there were the missionaries, who would convert the indigenous people. After the Constitution, a policy of non-contact came into force, in respect of those peoples who refuse to maintain a relationship with the Brazilian state. Some people show this refusal by firing arrows or escaping, others abandon the place where they live when they see that non-indigenous people or other people are getting close to them, still others set traps in an attempt to prevent non-indigenous people from advancing. What the state should do, based on the non-contact policy, is to mark out a safe territory for them. It is necessary to understand what territory they are occupying, based on monitoring that allows us to understand where they are going, and then demarcate it.

Why do you think Bruno was so fascinated by the so-called uncontacted peoples?

It’s hard to explain the passion. It is like me trying to explain why I am fascinated by the Javari Valley. But there is a side of Bruno that is more indigenous, really. He really liked the jungle a lot. He liked being there, he liked tracking animals, he liked planting things. He liked to learn with the Indians, this thing of signs, of hearing birds singing. What is the bird, what is the species, this intimate conversation that the Indians have with the forest. Bruno was really fascinated by this. This work with the uncontacted peoples, going on expeditions, put him very much in his element. I even used to get annoyed [she laughs]. Like spending a month away without missing us, you know. And no, he didn’t, because he had a spiritual and existential commitment to all of that. This relationship is also something that has a certain attraction for me, you know, these other alternatives of life. These other possible worlds. Even the indigenous people sometimes think of the uncontacted people as a possibility of going back to being isolated. Going back to living in the jungle. They live in the jungle, but when they talk about going back to the jungle, it is in this sense, of refusing all this junk that we force on them. Of getting away from all this shit, you know? There are these peoples who refuse, and this is a great power. So it is really fascinating. They are possibilities of life. I don’t want to make a projection of what interests us with this, you know. Like a perfect society and so on, this autonomy in the face of capitalism… It is important to point out that this refusal also means difficult choices, like dying from diseases that could be cured. And also saying that many are cornered, trapped, threatened with death. There is also that dimension. But it is beautiful to have another possible world. And they are resisting. And we have to make sure that they can continue to have clean water, have a place to walk, make sure that they don’t have to pay with their lives the price of refusing [the State].

Bruno was well-known for being obsessed with his work. How was this in your day-to-day personal lives?

He was very obsessed, he would think about it all day long, you know. There were days when I would say: “Bruno, let’s talk about children, let’s talk about music. But no, he was really obsessed. Like the phone would ring at three o’clock in the morning and he would wake up to answer it. This issue [of the uncontacted people] is full of really urgent stuff, you know? It was his passion. I am taking Bruno with me, taking this whole collective that together built the Observatory for the Human Rights of Uncontacted and Recently-contacted Peoples. There is no doubt whatsoever, that he would be occupying this position. So, I think it is a way of keeping Bruno alive.

Translated by Mark Murray

O indigenista Bruno Pereira em foto de outubro 2019, época em que foi afastado da Coordenação-Geral de Povos Isolados da Funai. Foto: Daniel Marenco/EFE