In a scenario where renewal of the Belo Monte hydropower plant’s operating license is pending an environmental analysis and conflicts have arisen with communities and federal agencies over how much water from the Xingu River can be dammed or released, Norte Energia, the consortium that owns the concession for the dam, has launched a media offensive to try to convince the general public of its relevance. The company invited journalists to visit plant facilities in Pará state, in the Amazon—but their tour didn’t include contact with the lives of those most heavily affected by the dam.

An article published in Folha de S.Paulo in early May says that despite the “roughly 1.4 billion dollars spent on social and environmental mitigations, twice the initial forecast and even including paying for public works,” Belo Monte “is still being criticized by environmentalists.” The news daily cites data strategically favorable to the hydropower plant, which entered operations about ten years ago, but little is said about ensuing problems or unfulfilled agreements. A report issued by Brazil’s environmental watchdog Ibama in 2024, for example, indicates that Norte Energia made good on just over half of the compensatory measures it had committed to in 2021 to mitigate damages along the downstream stretch of the river known as the Volta Grande do Xingu, one of the planet’s most biodiverse regions and one of the hardest hit by the mega-dam complex.

SUMAÚMA—based in Altamira, the vital center of Belo Monte—was monitoring the hydropower plant’s impact on the lives of human and more-than-human peoples in the region even before our news platform launched in September 2022. Complementing the dozens of articles SUMAÚMA has published on the topic, this report compiles technical information, documents, and personal accounts from people who go to bed and wake up every day missing the river and grappling with fish mortality, surging violence, and various other consequences of the project. People who are not “environmentalists” but whose lives were bound to the rhythm of the Xingu and whose homes were flooded as animals around them drowned, the fish they knew developed deformities, and the breeding grounds of new more-than-human lives became graveyards.

Here are eight facts about Belo Monte that Norte Energia didn’t show guest journalists during its media blitz:

Volta Grande do Xingu: downstream from the dam, water volume is so low that some stretches are nothing but rocks. Photo: Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

They took water from the river—and from people’s homes

Since the 1970s, when the Brazilian government announced its plans to build a hydroelectric power plant on the Xingu River, Gracinda Lima Magalhães, known as dona Gracinda, has been fighting the licensing of Belo Monte. In 2011, when the hydroplant’s operating license was granted, dona Gracinda—a civil servant for 35 years and currently a member of her municipal health board—realized the only solution was to engage in a daily struggle to ensure full compliance with the project’s mitigation programs.

“Our battle has always been to minimize the impacts of Belo Monte. I worked really hard in the fight over environmental licensing requirements related to health.” Dona Gracinda, who was personally affected by the project, had to move to one of the five urban resettlement areas provided for in the Belo Monte Environmental Impact Assessment. Norte Energia built the new subdivisions on the city outskirts to house families displaced from the area touched directly by the hydroplant. Many saw their homes in the Forest burned and flooded, and in the new neighborhoods they can’t even plant subsistence gardens like they used to. Their fishing canoes are marooned on dry land, kilometers from the river.

Basic sanitation in the subdivisions has never been finished, and for the past 15 years some houses have depended on water delivered by tank truck—but not on a regular basis, says dona Gracinda.

Tanker delivering water to a resettlement subdivision in Altamira: water supply is still erratic in many such neighborhoods. Photo: Soll/SUMAÚMA

The story of what Belo Monte has done is very long, Dona Gracinda warns. A key chapter concerns the way many of the families resettled in these subdivisions now live their lives. Some people never received any compensation because Norte Energia hasn’t recognized the impacts, she points out. Some resettlement areas are already fully occupied, and “many people still don’t have housing,” according to her. The municipality can’t afford the costs associated with the unfulfilled licensing requirements, Dona Gracinda tells us. “There are huge areas where there are no public services, not even a school,” she says.

Norte Energia adopted policies regarding water, sewage, and solid waste, including garbage collection and the construction of a landfill, in response to environmental licensing requirements. Put on display for the visiting press, the landfill was inaugurated in 2013 but reached its operational limit between 2021 and 2022, according to the federal Public Prosecutor’s Office, which claims waste is being dumped there unlawfully and that there are signs of leachate contamination.

Technical reports suggest errors in both planning and operation. Recently, in 2022, Norte Energia transferred responsibility for the landfill to the municipal administration, with the City of Altamira signing an agreement to take over management, maintenance, and operation of the sanitation system. The document leaves it clear that this responsibility encompasses all related costs. The city has been left with a time bomb since it simply does not have the resources for this.

Norte Energia is also obliged to guarantee universal access to Altamira’s water and sewage system, but the city estimates this won’t be accomplished until 2035. Data from the Brazil Sanitation Panel, compiled by the Trata Brasil Institute, indicate that in 2022 (the latest available public figures), 52.3% of Altamira’s population had no sewer and 50.6% had no treated water. However, after visiting Belo Monte at the invitation of Norte Energia, Folha de S.Paulo reproduced the information that 92% of the municipality is served by a sewage system, a figure found in the 2022 Sustainability Report released by Norte Energia, which cites neither the source of the number nor the underlying methodology.

Resettlement: subdivisions were built to receive families of Beiradeiros forced to leave their riverside homes. Photo: Lilo Clareto/Amazônia Real

Health impacts overburden public healthcare facilities

In information shared with its invited journalists and on its website, Norte Energia states that it has invested in health care, another of the company’s obligations. It also claims it has finished building three hospitals and 62 basic healthcare posts within the so-called Belo Monte area of influence (the municipalities of Altamira, Anapu, Senador José Porfírio, Vitória do Xingu, and Brasil Novo), which will benefit both Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities.

But the health and social damage Belo Monte has done to the populations of the Middle Xingu has been proven in scientific research—and is visible in the bodies of those who live there.

“We’re afraid of losing our future, our children’s and grandchildren’s future,” says Bel Juruna, an Indigenous leader of the Yudjá people who lives in Mïratu Village, in the Paquiçamba Indigenous Territory. For five years she was a health agent in the region; for six she has been a nursing assistant. The fear of having no tomorrow, Bel says, is reflected in the bodies and minds of the Indigenous people. “One of the things that shocks and saddens me the most during medical appointments, in the situation we’re living in today, is how high blood pressure has affected so many people. I think it has a lot to do with stress, insecurity, nerves, the changes they’ve gone through in their lives, and also their diet, with industrialized products,” she says.

Warnings about the potential repercussions of Belo Monte were sounded even before dam construction began in 2011. In 2009, a panel of experts made up of 38 scientists representing different Brazilian and international institutions and diverse fields of knowledge released a 230-page critical analysis of the Belo Monte Environmental Impact Assessment, and it predicted devastating consequences. The researchers warned that the environmental assessment and statement, as well as the health-related program proposals submitted to the federal environmental agency Ibama by Norte Energia as part of its licensing application, seriously underestimated the potential spread of diseases and environmental degradation.

Projections of Belo Monte’s negative impacts on public health systems were so limited, inadequate, and incomplete that they minimized the effects of both the population explosion in municipalities lying within the project’s area of influence as well as the spread of diseases on a scale that is still unpredictable. From 2010, a year before construction began, to 2022, the most recent census year, the city registered a geometric population growth rate of 2.04%, surpassing the figure for Brazil as a whole (0.52%) and for Belém, capital of Pará (down 0.55%). Altamira’s population went from 99,075 to 126,279. In the panel’s report, public health specialists Rosa Carmina de Sena Couto and José Marcos da Silva stated that Norte Energia should have submitted a mitigation program based on direct financing sources, without relying on counterpart funds from the government.

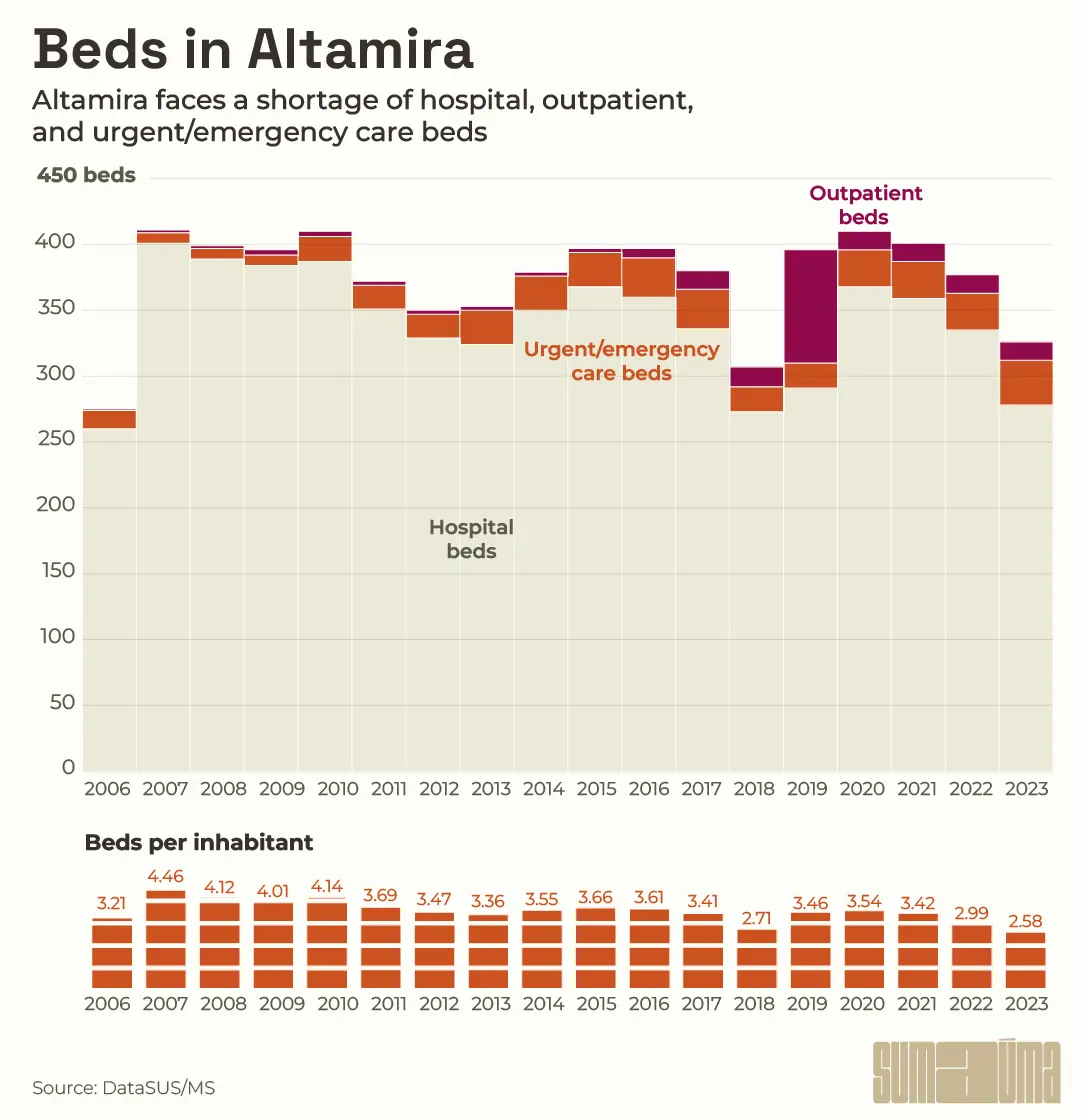

In a peer-reviewed paper that was based on his 2021 master’s thesis, Antonio Carlos Lima, professor of medicine at the Federal University of Pará, evaluated the compensation measures Norte Energia adopted in Altamira. One of the company’s commitments was to collaborate in the provision of universal access to health care in the city. In his study, the professor concluded that, “despite investments in primary health care, the region still saw gaps in assistance.” According to his research, the plan did not provide for adequate expansion of the already-overburdened healthcare network to cover urgent and emergency care facilities, hospital beds, and medical specialties such as psychiatry, cardiology, and neurology. Professor Lima, who formerly served as health secretary for the municipality of Senador José Porfírio, told SUMAÚMA the situation remains unchanged and “much of what was proposed has not really been implemented or complied with.” He pointed to the shortage of hospital beds as one of the most serious problems in the Xingu region, where an additional 40 ICU beds and another 100 hospital beds are needed. According to a study by the government of Pará, drawn from Brazilian health ministry data, Altamira had 3.69 beds per thousand inhabitants in 2011, when work began on Belo Monte; the latest data available, from 2023, show the average had fallen to 2.58 beds.

InfogrAPHIC: Rodolfo Almeida/SUMAÚMA

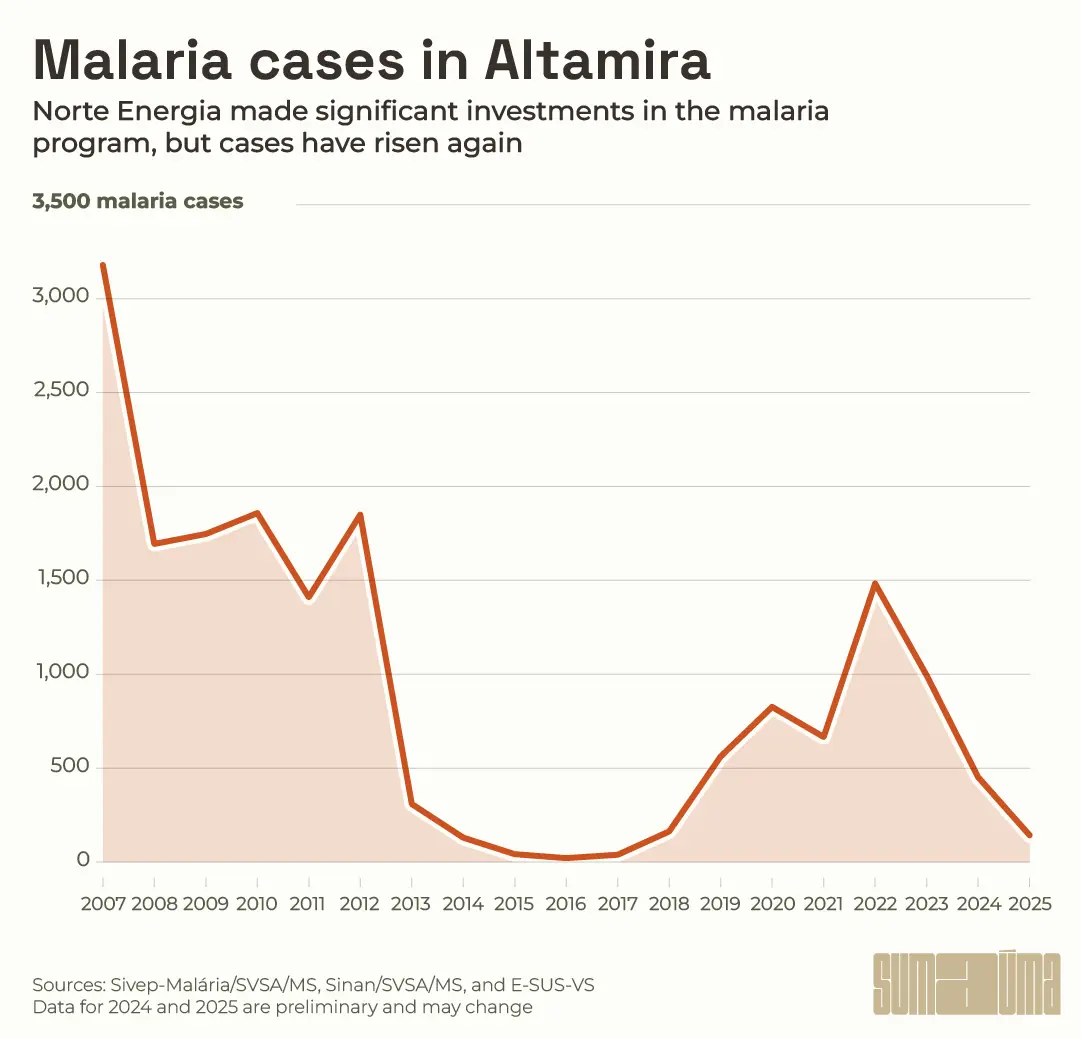

Another endeavor offered as a success story by Norte Energia is the Malaria Control Action Program, implemented by the company in 2011-2024. In 2021-2023, the company had a formal agreement with the environmental agency Ibama, under which it would maintain investments in the program. While it is true the program achieved excellent results, the company failed to address certain aspects of it.

Professor Osvaldo Correia Damasceno, from the Federal University of Pará medical school in Altamira, explains that fighting malaria entails periodic interventions in which there is some control over factors, as long as the work is structured and supervised. Other health problems, like chronic and mental illnesses, are associated with a set of factors that are difficult to measure and are much more expensive to control.

“Non-communicable chronic illnesses have had a huge impact on the Indigenous population. The first time I went to Cachoeira Seca, in 2019, there were two diabetics. The last time, in 2025, there were 20. But a number of these impacts aren’t measured because it’s hard to do research with Indigenous populations and not much data has been published. That’s why it’s easier to access data on infectious diseases whose reporting is mandatory, like malaria,” says psychiatrist Érika Fernandes Costa Pellegrino, a professor at the Federal University of Pará. Pellegrino, who has lived in the city since 2017, is part of Altamira’s Living Well Network, which provides psychosocial care to Indigenous people in the region, especially in the Cachoeira Seca Indigenous Territory.

According to Pellegrino—who wrote her doctoral dissertation on psychic suffering and Belo Monte—chronic illnesses, mental health issues, and violence against women, for example, are not subject to mandatory reporting; moreover, diagnosing them takes time and treatment is more complex and demands greater investments. And it’s hard to successfully reach a goal in a short period of time.

Professor Damasceno, who is currently coordinator of health surveillance in Altamira, says there has been a “significant reduction” in Norte Energia investments in the malaria program, especially since 2020, with actions directed solely at the stretch of reduced flow along the river. As a result, rates of the illness have climbed again. In 2022, for example, the number of cases reported in the municipality—1,483—was around the same as in 2011, according to data collected by SUMAÚMA from DataSUS, the national health service’s databank. The figure slumped again the following year. With hydroelectric power plants, he says, mitigation policy needs to be continuous, without any interruptions.

“The urbanization process has also led to an increase in external problems (violence, accidents). Legislation [licensing] for the construction of hydroelectric power plants provides for a more organized plan for addressing malaria. For other diseases, this isn’t as effective. In part because the most consequential social factors tend to be harder to mitigate.”

InfogrAPHIC: Rodolfo Almeida/SUMAÚMA

In the five municipalities within the dam’s area of influence, cases of congenital syphilis—transmitted from mother to baby during pregnancy—rose from an average of 12 a year in 2007-2009 to 24 a year in 2010-2023, the latest data available from DataSUS. Altamira, the most impacted town, saw spikes in 2011 (28 cases), the year construction began, and then again in 2018 (39 cases), the year work was drawing to a close on the last turbine.

Bel Juruna confirms that health care is uncertain in the region. “It’s really hard to be seen at a hospital or get an appointment. There’s more alcoholism in the villages and more cases of syphilis in the communities. Diseases have increased but not health care.” Bel, who works in Indigenous health, says she has witnessed growing cases of mental health problems, diabetes, and hypertension in some villages, exacerbated by the radical, involuntary changes in diet occasioned by Norte Energia’s Emergency Plan, which introduced industrialized food to affected villages, including the Arara of Cachoeira Seca, a recently contacted people. The 2024-2027 Special Indigenous Health District Plan reports a rise in infectious, sexually transmitted, and chronic diseases and alcohol and drug abuse, among others, in 12 Indigenous territories and among Indigenous peoples in Altamira and the Volta Grande do Xingu.

Less water, less fish, less life

If the trip sponsored by Norte Energia had taken reporters along the Volta Grande stretch of the Xingu, they would not only have observed one of the Amazon’s most biodiverse regions and one hardest hit by the dam. They also could have visited the Paquiçamba Indigenous Territory and met Josiel Juruna. A leader of the Juruna people, Josiel could have explained how the quantity of fish he sees and catches every day has dropped precipitously since Belo Monte. “We used to eat tiger fish, spotted catfish, redtail catfish—and there were a lot. Now these species are really scarce. It’s really hard for you to catch them,” Josiel told SUMAÚMA.

Josiel Juruna, Indigenous researcher, gathers fish eggs: shriveled up in the sand, they will never hatch. Photos: Wajã Xipai/SUMAÚMA and Josiel Juruna

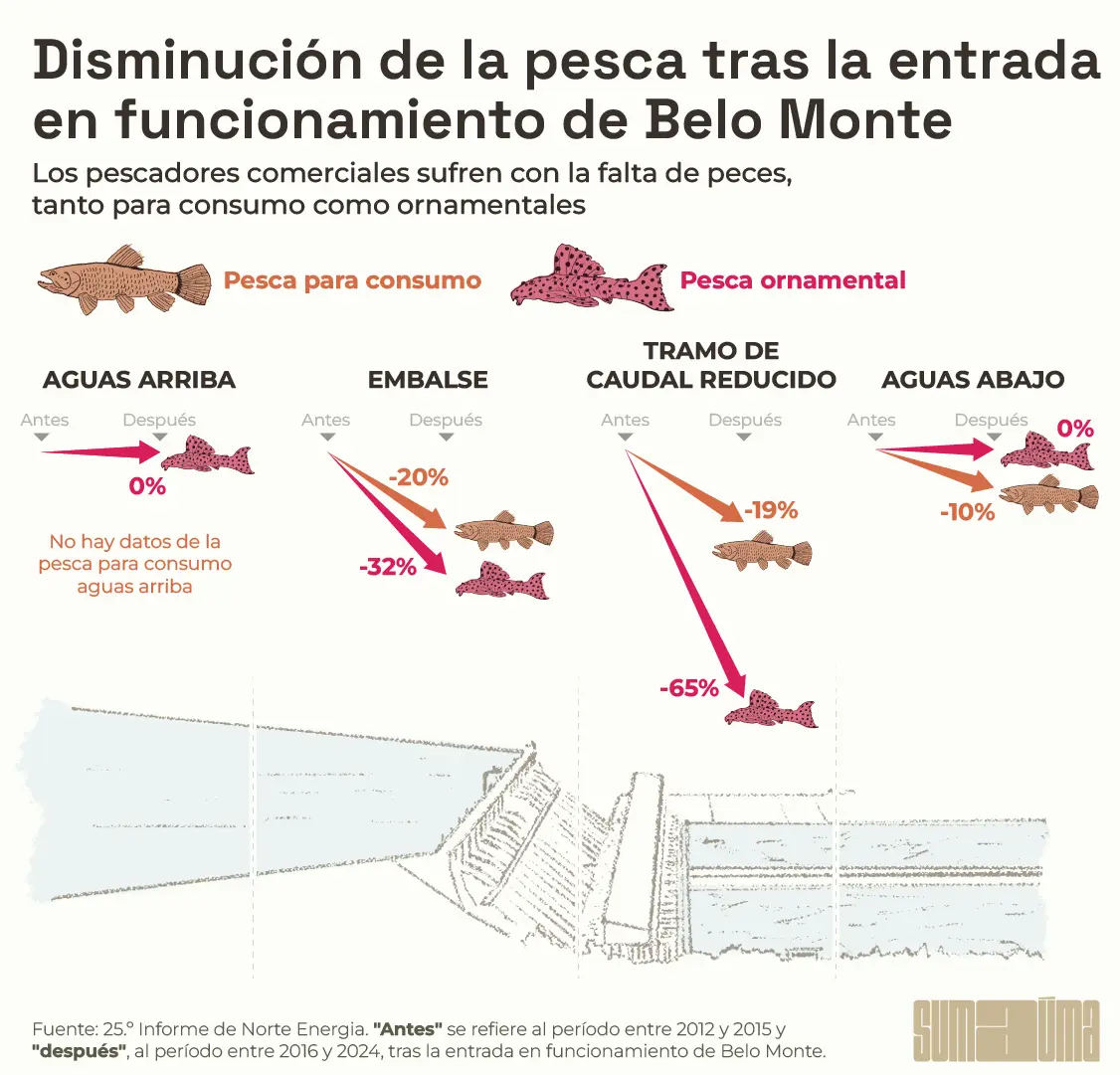

The reduction in fish was also mentioned in 100% of the complaints made by fishers in the Altamira region during a survey published in the Federal University of Pará geography journal. In its latest document on Norte Energia’s environmental impact assessments, Ibama agreed with this evaluation by Indigenous people and fishers. Comparing 2012-2015, the period before the reservoir was filled, with 2016-2023, the agency found “significant reductions in the wealth and abundance of fish.”

Among the most heavily impacted areas was the Volta Grande, where Juruna land lies, downstream from the dam. The hydropower plant destroyed habitats vital to some species and interrupted over 80% of the water flow to the region. And the situation is getting worse.

In the document released by Ibama on March 18, 2025, which analyzes data through 2023, the environmental agency highlights the decline in eggs and larvae. “These factors indicate that population recruitment may be compromised, and in the long run this might affect the sustainability of [fish] populations,” according to the text.

In 2023, SUMAÚMA revealed spawning grounds have been transformed into graveyards, with millions of dead fish eggs lying on dry riverbanks. “During the dry season, the eggs are a sign of how many fish could become adults but won’t be able to anymore,” says Josiel Juruna.

InfogrAPHIC: Rodolfo Almeida/SUMAÚMA

Josiel is a researcher with the Independent Environmental Territorial Monitoring Project, which observes conditions on the Xingu with the collaboration of university researchers, Ribeirinhos, and Indigenous people. One of their studies found that the average weight of catches per fishing trip has dropped. Before the dam, fishers were able to capture 68 kilos of characin, but after construction the average sank to 5.4 kilos. Catches of croaker plummeted from 99 kilos to 1.7 kilos and spotted catfish, from 41 kilos to 1.8 kilos.

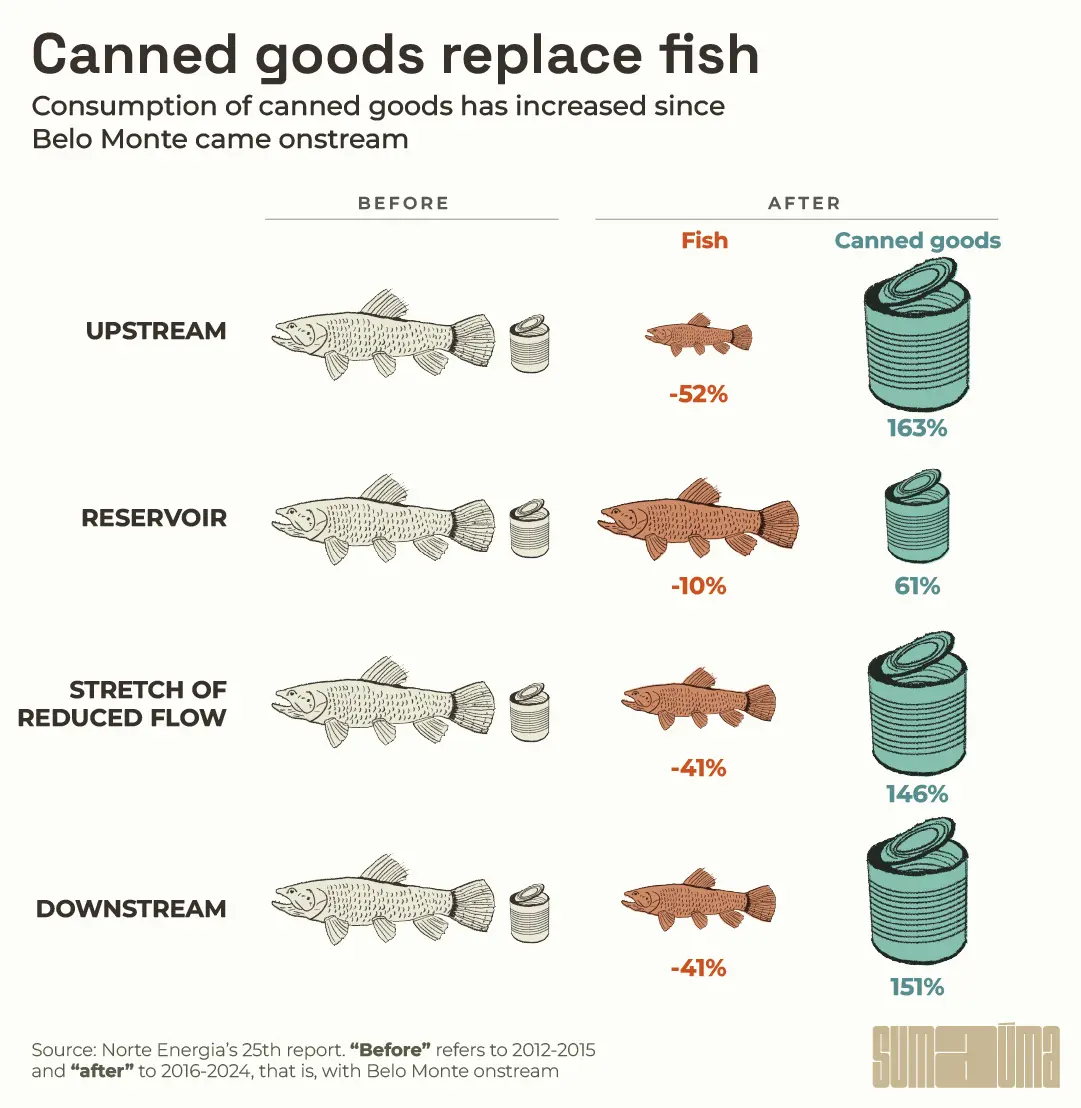

Norte Energia’s 25th report, not yet analyzed by Ibama, admits that commercial fishing catches fell by as much as 20% after the reservoirs were filled, with ornamental fishing down by as much as 65%. Another survey on food security in Ribeirinho communities detected a 58.5% drop in fish consumption in the Belo Monte region.

Norte Energia’s own report presents even more shocking data: in regions affected by the dam, fish consumption decreased between 41% and 52%. Consumption of canned goods rose up to 163% and of cow’s milk at least 168%. The dam not only wiped out fish—it also altered the local population’s entire way of life.

InfogrAPHIC: Rodolfo Almeida/SUMAÚMA

Unfulfilled commitments on the Volta Grande do Xingu

In February 2021, the environmental agency Ibama signed an agreement with Norte Energia authorizing Belo Monte to operate temporarily according to one of the company’s preferred hydrographs, or water management plans, which defines how much water goes into the turbines and how much is left to sustain the life of the Xingu. In exchange, Norte Energia pledged to invest 29.2 million dollars in measures to “monitor, control, and mitigate impacts” along the Volta Grande do Xingu. The measures in themselves were nothing new; most had been on the list of company obligations since the hydroplant’s construction and operating licenses were issued.

The document, called an Environmental Commitment Agreement, foresaw 141 mitigation actions across 14 projects, including 20 actions in the realm of human healthcare, food distribution to fish and turtles, and forest restoration in Permanent Preservation Areas. In a document from October 2024, where Ibama analyzes Norte Energia’s performance, the agency is emphatic: “Incomplete actions account for approximately 45%” of the total.

Nor have the results of completed actions been satisfactory. One example: in a food supplementation project for more-than-humans whose habitat has been threatened by Belo Monte there was “no direct relation between the food offered and the food actually consumed by fish and yellow-spotted river turtles,” according to Ibama staff. “There is no evidence that food supplementation improves either the body condition of the fish and turtles or the reproductive activity of the analyzed species,” agency staff concluded.

Although Norte Energia “sells” the idea that it is carrying out activities that should fall to the state, the company didn’t even finish what it had proposed to do under an agreement advantageous to it. “We’ve got deformed fish, with hardened eggs in their bellies, who can’t spawn. And they’re thin, very thin,” says Raimundo da Cruz e Silva, a Ribeirinho who lives in Anapu, an area of the Volta Grande do Xingu that has suffered greatly since Belo Monte dammed the river.

Raimundo da Cruz e Silva monitors breeding grounds: lower water levels are turning nurseries into graveyards. Photo: Soll/SUMAÚMA

A letter dated October 2024, submitted to the federal Public Prosecutor’s Office by the Yudjá-Juruna people of the Paquiçamba Indigenous Territory, in the Volta Grande do Xingu, exposes another issue. “Before the dam was built, our income [came from] fishing for consumption and ornamental purposes. We had to become farmers of food and fish, without any effective support, [and] we lost our food sovereignty. We’ve spent years struggling to plant cacao and raise fish in aquaculture tanks.”

Without proper assistance, cocoa produces little. Technicians from the Executive Commission of the Cocoa Crop Plan, a research institute under the ministry of agriculture, investigated cocoa planting in Mïratu, a village in the Paquiçamba Indigenous Territory, and their report pointed to problems. In their letter, the Indigenous people complained that “they didn’t have proper technical assistance, [and also] lacked support in preparing the area, clearing native vegetation, and using seedlings, without having the institute’s oversight.”

This impression was corroborated by the executive commission. An excerpt from the report, included in the letter sent to the Public Prosecutor’s Office by the Yudjá-Juruna, reads: “When the areas were selected for planting, no soil analysis was done nor were the physical characteristics of the area checked, such as, for example, soil depth, which is a fundamentally important aspect for the cacao tree, a plant that requires a minimum depth of 1.5 meters. It isn’t feasible to grow cacao in shallow or rocky soil.”

Ibama also identified issues with programs that encourage cacao planting. It said Norte Energia itself “advised that it is not feasible to implement the projects.” The agency added: “the information that this is not feasible is not acceptable. The company needs to find a solution that makes the projects it planned feasible, primarily those projects for which it filed feasibility reports.”

Even drinking water is now scarce in the Volta Grande, right on the banks of the Xingu, one of the Amazon’s largest rivers. Ibama found the installation and improvement of wells “insufficient.” Norte Energia justified itself to agency staff by claiming that “the problem in completing the task stems from failures in well drilling.” As an “emergency measure,” the company delivered ceramic filters and drinking water to residents. In 2023, Ibama had warned that “the distribution of filters may not be enough to guarantee the availability of drinking water.”

The environmental agency was categorical in its conclusion: “The failure of mitigating measures leads us once again to inform the competent authorities that this project has generated unacceptable social impacts that mean Ribeirinhos on the Volta Grande do Xingu have lost their way of life.”

SUMAÚMA asked Ibama’s management about the matter. Their response, forwarded in writing by the agency’s press office, is that the technical report finalized in October 2024 “is undergoing internal analysis, for later due processing.”

Striking changes: Healthy croaker on left; deformed croaker on right, with a shorter, rounder spine. Photo: Sara Lima

Murder rate skyrockets in Altamira

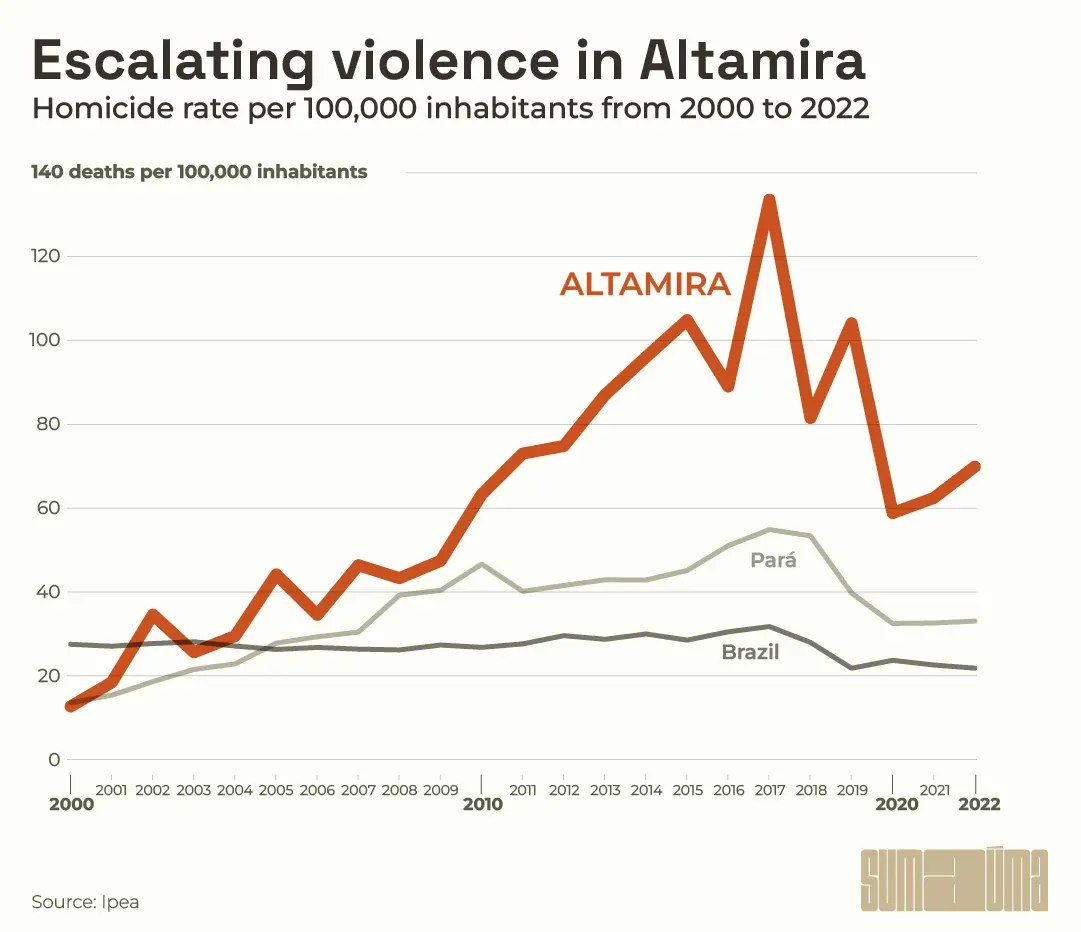

All available data—from Brazil’s national healthcare system, the Pará State Department of Public Safety, academic studies, and special publications produced by organizations such as the Brazilian Forum on Public Safety—are unanimous in pointing out that violence in Altamira has risen exponentially since construction of the Belo Monte dam complex.

Not that Altamira used to be peaceful. In 2010, the city had a population of nearly 100,000, and the homicide rate, trending upward since 2000, had reached 63 per 100,000 inhabitants, topping the figure for Pará (46.4) and well above the Brazilian average (27.8). A report by the Brazilian Forum on Public Safety shows the Brazilian Amazon has recorded higher rates of deadly violence than the national average since 2012, in a context associated with environmental crime, land conflicts, and faction disputes over narcotrafficking routes.

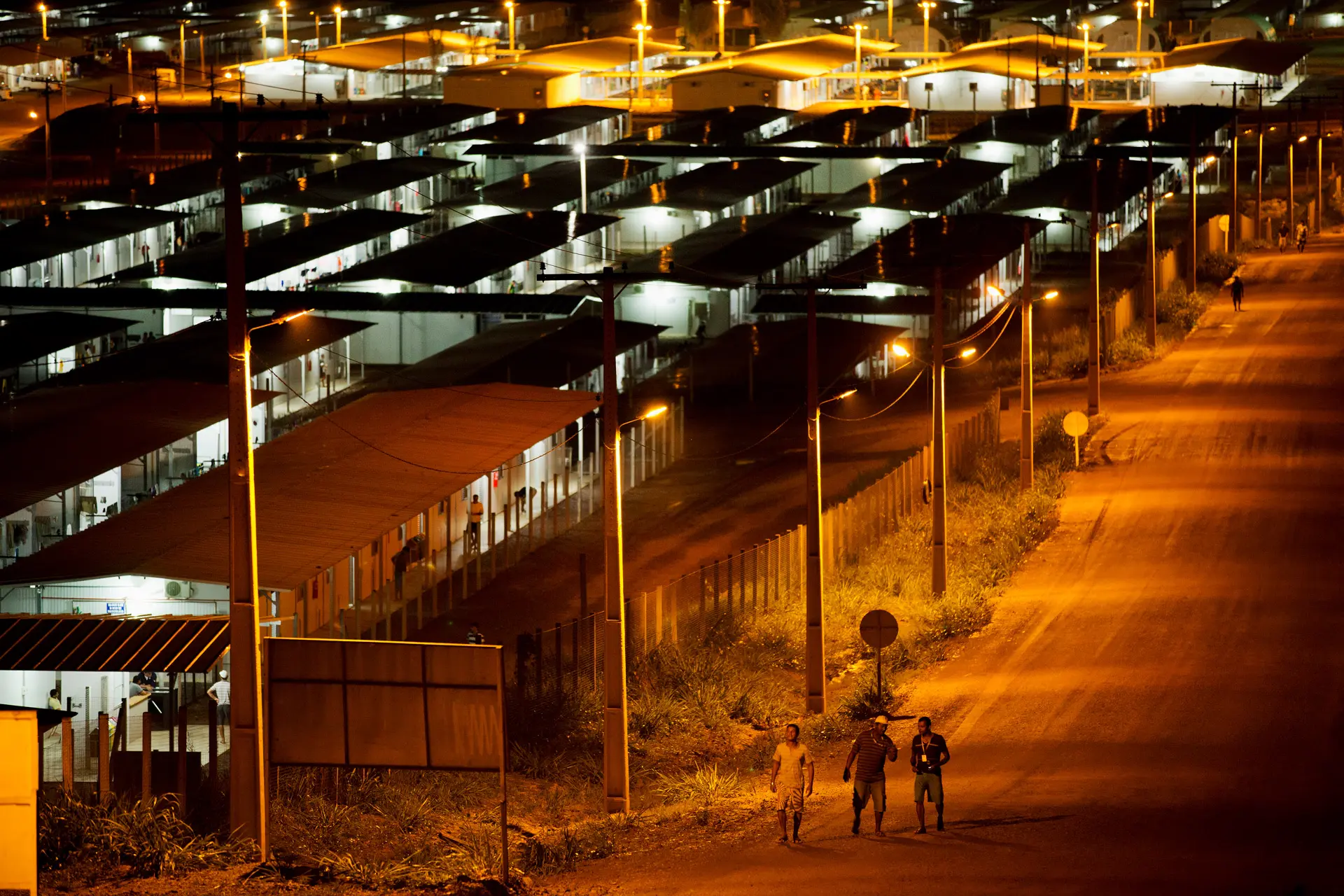

In Altamira, rivalries between drug factions have come on top of a population explosion triggered by construction of the dam, without a corresponding provision of new urban infrastructure. In 2012, the city saw an influx of nine thousand workers, according to press reports from the time, with the figure jumping to twenty thousand the following year. Entire communities were kicked off their land and relocated to urban resettlements far from downtown. Families were forced to move, old businesses closed while new ones opened, and prices on everything soared, particularly rent. The 2022 census put the population of Altamira at 126,279, an increase of 27.4% in just 13 years, at a time when Brazil was witnessing slower demographic growth overall.

Work camp during construction of Belo Monte, 2013: the population explosion and thriving drug trade have boosted crime rates. Photo: Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

The number of murders rose from 64 in 2010 to 114 in 2015, the year Altamira became the most violent of Brazilian municipalities with populations over 100,000, based on a homicide rate of 105 murders per 100,000 inhabitants. In 2017, the city saw a record 149 murders, bringing the rate to 133 per 100,000. In the mid-2010s, clashes between criminal groups intensified. In 2019, an uprising by inmates from rival factions at the Regional Recovery Center of Altamira penitentiary ended with 62 deaths, the second-largest prison massacre in Brazil’s history. The only time more lives were lost was at the Carandiru penitentiary in São Paulo, in 1992, when 111 prisoners were killed.

In his master’s thesis, defended in 2022 at the Federal University of Pará, geographer Igor Renan Araújo Oliveira examines indicators of violence in Altamira and points out the relationships between these rates and the Belo Monte project, the increase in population, and drug trafficking in the region. From 2000 to 2010, the city saw 371 homicides, compared with 984 from 2010 to 2019.

InfogrAPHIC: Rodolfo Almeida/SUMAÚMA

“The city has always lacked public services and was already experiencing problems with drug trafficking. Belo Monte amplified all of that,” Igor said. “Altamira turned into a goldmine for trafficking. It has become impossible to spend time on the city’s waterfront along the Xingu River.” When construction of Belo Monte ended, thousands of newly jobless people remained in the city in socially vulnerable circumstances.

Although focused on homicides, Igor’s study also shows an increase in other police incidents, such as theft and drug seizures. Reported rapes, 43 in 2010, reached 92 in 2018, according to the Pará State Department of Public Safety. “For a woman, it’s become very dangerous to go out on the street,” said the 33-year-old geographer, now a technical specialist for Pará’s Public Prosecutor’s Office in Altamira.

His study also showed that the deadliest side of criminality, homicides, predominantly targeted the young: the average age of murder victims from 2010 to 2020 was 29. Igor’s thesis is dedicated to two of those victims: his friends Magid Mauad, a fellow geography student, and Ruan Silva, an environmental engineer. Magid and Ruan were murdered by drug traffickers in Altamira in 2017 and 2020, respectively. Founded by Magid’s mother, Málaque Mauad, as a way of pushing for the investigation of these murders, the Mothers of the Xingu collective was born from the anguish of families who had lost so many young people. “The city didn’t have the infrastructure to absorb so many people. Our daughters couldn’t even go out. After they killed my son, I decided I wouldn’t stay silent. The mothers never talked, but I decided to,” she said.

Málaque’s initiative drew in other women who had lost their children to violence in the city. In 2020, when Altamira suffered a wave of youth death by suicide, Mothers of the Xingu took up the fight to support survivors, that is, both the families of the dead and the youth who had tried to kill themselves. Today the group has around 25 women and is involved in both the Council for Women and the Council for Children and Teens in Altamira.

“Over the years, the scale of violence has snowballed due to a combination of problems stemming from the Belo Monte project: a sharp population influx, more drug use, more violence, more homicides, economic stagnation post-Belo Monte, increased unemployment, and the advent of conflicts between criminal factions in the urban context of Altamira,” Igor concludes.

In recent years, crime has declined in Altamira but still remains at extremely high levels. According to the violence map released this month, the homicide rate in the city was 62.6 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2023, compared with 21.2 for Brazil overall. According to all available databases of violence, since the construction of Belo Monte, Altamira has become one of the most dangerous places to live in Brazil.

Málaque Mauad and Magid on their last Mother’s Day together: after her son’s murder, she founded the Mothers of the Xingu collective. Photo: Personal archives

More deforestation on Indigenous territories near the dam

Construction of Belo Monte was accompanied by a rise in deforestation in the four Indigenous territories within the dam’s area of influence: Cachoeira Seca, Ituna/Itatá, Trincheira Bacajá, and Apyterewa. This was shown in an analysis released by Rede Xingu+ in 2022, as reported by SUMAÚMA in 2023.

“In 2019 and 2020, deforestation in the four Indigenous territories in Pará [under the influence of Belo Monte] outstripped deforestation in the other 311 Indigenous areas [in Brazil’s so-called Legal Amazon]. The years 2018 and 2019 saw a tremendous spike in deforestation rates, with increases of 175% and 194% over the immediately preceding years.” In 2019 alone, more than 30,000 hectares of forest were lost in the four Indigenous territories near Belo Monte. That’s the equivalent of “61% of the total deforestation of Indigenous areas in the Legal Amazon,” the Rede Xingu+ report notes.

According to a 2022 report by the federal Public Prosecutor’s Office, protecting Indigenous territories in its area of influence is yet another of the environmental requirements on Belo Monte’s construction that Norte Energia didn’t adequately fulfill. Located about 45 kilometers from the Belo Monte dam complex, the Ituna/Itatá Indigenous Territory is 142,000 hectares—almost the size of the city of São Paulo—and home to an Indigenous group known as the “isolated people of Igarapé Ipiaçava, who have avoided outside contact.” The unprotected territory became the target of greedy land-grabbers, who started raising cattle there. From 2018 to 2021, Ituna/Itatá was one of the top three most deforested Indigenous territories in Brazil. In 2019, the first year of Jair Bolsonaro’s far-right government, it was the territory that suffered the most destruction, losing 12,000 hectares of forest, a staggering 656% increase compared with 2018.

SUMAÚMA spent three days in Ituna/Itatá in August 2023, accompanying agents from Ibama and other federal agencies who were beginning the long process—concluded only in 2025—of removing 5,000 head of cattle being raised on Indigenous land illegally. Scenes from a war zone. The criminals destroyed already-fragile bridges and burned forest in an attempt to prevent the removal of the illegal cattle. They weren’t even deterred by the presence of armed agents from the National Public Security Force, Federal Police, and Federal Highway Patrol.

Cattle raised illegally inside Ituna Itatá, 2023: This Indigenous territory was among the most heavily deforested in Brazil. Photo: Lela Beltrão/SUMAÚMA

“The analysis suggests that increased deforestation on Indigenous lands and the area around Belo Monte is associated with the dismissal of the workforce [who built the hydroelectric facility], noncompliance with licensing requirements regarding both the territorial protection of Indigenous people as well as land regularization, and [Norte Energia’s] inadequate compliance to the requirement to support actions to contain deforestation,” the Xingu+ report states. And it was predictable: the Environmental Impact Assessment done before Belo Monte was built had already anticipated all this would happen.

For Ibama, however, the Belo Monte environmental licensing process “does not provide any information that would enable identification of any direct cause-and-effect relationship between the project and deforestation in the region.” When asked about the matter, the agency’s press office stated that “in the period from 2016 to 2022, increases in deforestation were registered throughout the Amazon region, which makes it complicated to determine a single cause.”

Norte Energia drags heels on reparations for Ribeirinhos

It’s been 10 years since Raimundo Berro Grosso had to abandon his house on the banks of the Xingu and move to the outskirts of Altamira, where he lives in an urban resettlement. His family was one of the approximately 300 that were expelled from the river’s islands and shores in 2015, when the Belo Monte reservoir was filled. He is still waiting for Norte Energia to fulfill one of the requirements for license renewal: the purchase of land to create a Ribeirinho Territory, the reparation promised this traditional community. As time went by, disillusionment set in: “I don’t want to stay here; I want to go back to my land. But because the territory is taking so long and given my health issues, I’m practically being forced to stay here,” said Raimundo, who has had a stroke and was diagnosed with Parkinson’s.

The specific situation of these Ribeirinhos—who had traditionally lived along the banks of the Xingu but also had places in town for when they went to market—was not taken into consideration during Belo Monte’s licensing. In 2015, when the reservoir was filled, they asked federal prosecutor Thais Santi for help. Santi defends the rights of Indigenous and traditional communities in Altamira. She approached the Brazilian Society for the Advancement of Science, which asked renowned researchers—including anthropologists Manuela Carneiro da Cunha and Sônia Magalhães—to interview the Ribeirinhos and study their way of life. Their work resulted in a book on the expulsion of Ribeirinhos from Belo Monte, whose findings were first presented in 2016.

The initiative led to the Ribeirinho Territory proposal and the formation of a Ribeirinho Council, made up of Beiradeiros expelled by the hydroplant; Raimundo Berro Grosso is one of its members. In 2018, the proposal was accepted as a condition to be met by Norte Energia. The technical plans were ready in 2019, but no progress has been made since.

On April 7, 2025, in a statement published on its website, Ibama once again demanded that Norte Energia buy the land. The next day, April 8, the company challenged the statement in an official letter. There was something curious about the letter: it was addressed not only to Ibama’s environmental licensing director, Claudia Jeanne da Silva Barros, but also to Mines and Energy Minister Alexandre Silveira and the President’s Chief of Staff, Rui Costa—two ministers who are often at odds with the government’s environmental agenda.

Ibama’s statement and the rebuttal from Norte Energia revolve around the most recent confrontation between the two sides. The dam operator has been moving Ribeirinhos to the Tavaquara resettlement. The company alleges that families who have given up on ever seeing a Ribeirinho Territory and are “socially vulnerable” are pressuring them for alternative housing. In most of those cases, they are families who received “occupation sites” inside the reservoir’s Permanent Preservation Area. Ibama feels that exchanging sites in the Permanent Preservation Area for houses in the Tavaquara resettlement “does not replicate the Ribeirinho way of life.”

Since 2016 Norte Energia has distributed a total of 157 occupation sites in the Permanent Preservation Area of the Belo Monte reservoir. The problem is this is a provisional measure that doesn’t consider the needs of the Ribeirinhos, since the Permanent Preservation Area has restrictions on crops and livestock. “You’ve got an area of 25 square meters to build your house and another little area for a vegetable patch. That really is an insult,” Raimundo Berro Grosso said.

Raimundo Gomes at his home in the Água Azul resettlement: “It’s an insult.” Photo: Soll/Sumaúma

That’s why, as the April 7 statement mentioned, Ibama has vetoed the transfer of more families to the banks of the reservoir, arguing that this provisional solution would effectively help delay implementation of the Ribeirinho Territory. Permission for new housing at occupation sites […] depends fundamentally on the acquisition of the adjacent land,” [i.e., land contiguous to the reservoir’s Permanent Preservation Area], Ibama stated.

The idea is that on these lands adjacent to the preservation area, each family is guaranteed space for planting crops and raising livestock, with the option to sell part of what they produce, like they did before Belo Monte. Encompassing a total of 8,400 hectares, three different sections of land have been marked for expropriation on both sides of the Xingu River not far from Altamira.

Norte Energia has been postponing the land purchase since 2019, citing a range of reasons. In the first years, the company alleged that most of the property owners didn’t want to sell their land. They also argued they had to wait for Brazil’s electric power regulating agency Aneel to facilitate expropriation by issuing an Eminent Domain Statement for these properties.

After Aneel issued the statement in mid-2024, Norte Energia presented a timeline for the purchase of the land. However, it stipulated prerequisites to be met before they would begin the process, including a new survey to establish how many families were still interested in the Ribeirinho Territory. It turned out that the company had already checked into this between late 2022 and early 2023. At the time, 267 families were polled, and only 42, or 16%, said they were no longer interested in the project.

The company also asked that the territory’s legal structure be defined now; the original idea was that land ownership would be collective. Norte Energia also argues it is awaiting a decision from Brazil’s land reform agency Incra about the availability of an area included in the Ribeirinho Territory where a settlement project already exists. Incra said it is aware of the situation and is planning a visit to the site “in the coming weeks” to identify the occupants of the area and determine how to deal with the issue.

In any case, Ibama never required all the land to be bought at once; families could move to their lots in the Ribeirinho Territory in phases. In February of 2023, for example, Ibama forwarded a letter to Norte Energia from five landowners interested in selling their properties, but nothing has been purchased to date. In a technical document dated April 2025, Ibama makes it clear that the “Ribeirinho proposal establishes three large territories involving the purchase of lands adjacent [to the reservoir’s preservation area].” “The agencies that have power—Ibama, the Public Prosecutor’s Office—have left things too lax. And the company is dragging its heels and hoping it’ll tire people out,” Raimundo Berro Grosso said.

When asked if the agency had already fined Norte Energia over the matter of the Ribeirinho Territory, Ibama said it “confirmed the delay in project execution” but “as yet this cannot be characterized as a failure to meet requirements.” Asked if it agreed with the terms the company wants to impose before buying the land, the environmental agency said that “at the moment this issue is under discussion with the parties involved in the Ribeirinho project (MPF, in full Ibama, Norte Energia, the Ribeirinho Council, and supporters).”

Young girl in a flooded home: the neighborhood where she lived was invaded by waters from the Belo Monte dam. Photo: Aaron Vincent Elkaim/The Alexia Foundation

New dam or bargaining chip?

The management of Norte Energia informed its guest reporters from Brazil’s main newspapers of its intention to build a new reservoir for the hydroelectric dam complex, which would flood an area of 1,000 square kilometers. Through the Access to Information Law, SUMAÚMA found that the Lula government has been aware of the plan since at least November 27, 2024. On that day, officials from the ministry of mines and energy and the Office of the Chief of Staff were visited by executives from the company, who presented “an initial study on the construction of a reservoir near [the] Belo Monte [hydroplant] on the Xingu River.” According to the minutes of the meeting, “the participants understood the importance of the analysis and asked Norte Energia for more details so the matter could be presented to Ibama and other interested agencies.”

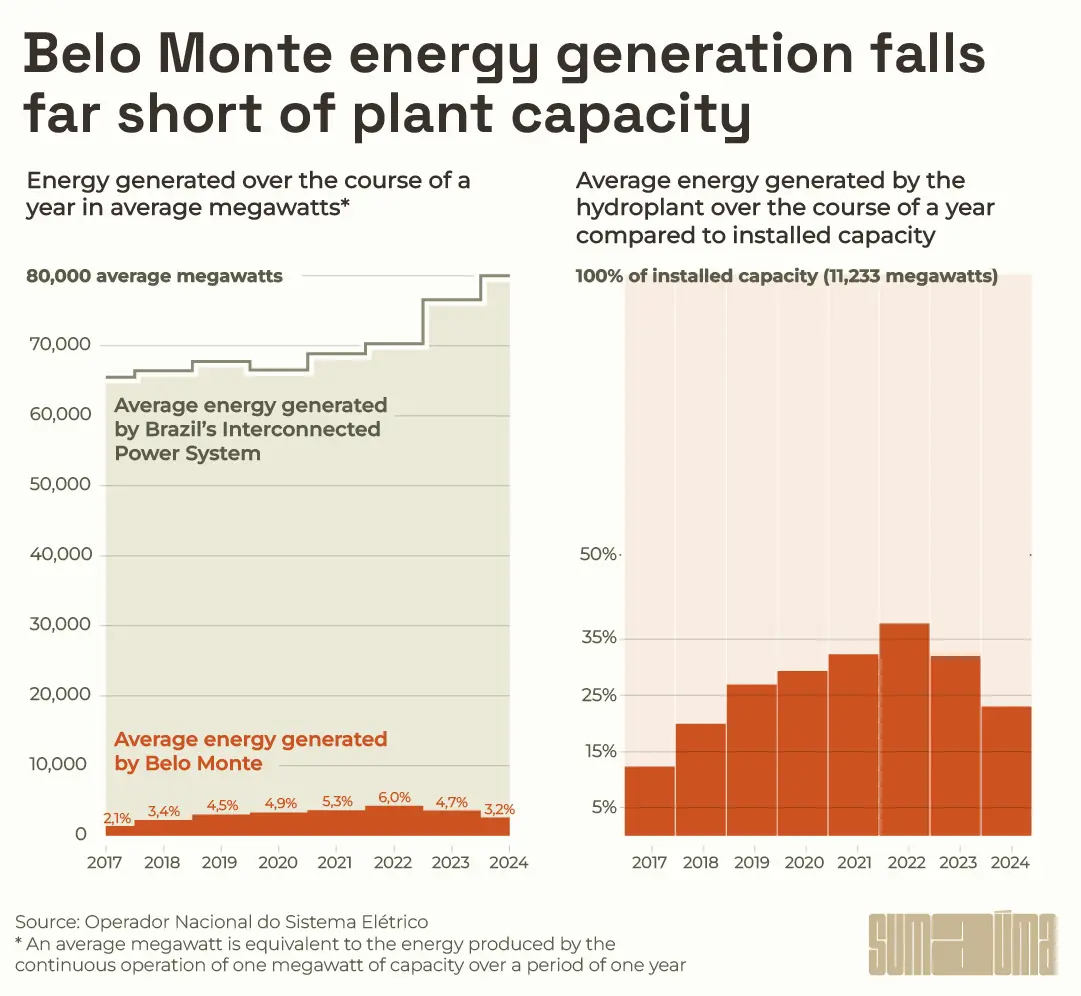

The proposal for a new reservoir, under the pretext of increasing the plant’s production, comes as no surprise to anyone who read a report released by a panel of 38 scientists in October 2009, before the Belo Monte construction license was issued. That document stated that the hydroplant would be uneconomical, that is, that the energy it would deliver to the electricity grid would not compensate for its cost. Because of the variation in the flow of the Xingu River throughout the year, the study predicted that, on average, the plant would fall far short of delivering on the energy generation potential of its turbines, which is 11,200 megawatts and second only to the 14,000 megawatts of Itaipu dam, built during the business-military dictatorship (1964-1985), when environmental licensing didn’t exist.

The prediction has come true, with an added exacerbating factor: the 2009 report didn’t consider the impact of climate change on Amazonian rivers. Since then, research has confirmed the rise in the planet’s temperature is likely to lengthen the dry season and reduce rainfall in the region. The consequences of this for hydropower plants in the biome were projected in the study “Brasil 2040,” commissioned by the Department for Strategic Affairs during the Dilma Rousseff (PT) government and shelved after its release in 2015. The study estimated that the flow of the Xingu at Belo Monte could fall by 25% to 55%.

The efficiency of an electricity source is defined by its “capacity factor,” which is the ratio between the energy it actually generates and the energy it can theoretically generate. On average, Brazilian hydroelectric plants have a capacity factor of 55%, according to the publicly owned Energy Research Company, linked to the mines and energy ministry. The expected capacity factor for Belo Monte was around 40%. However, the plant’s annual performance, including rainy and dry seasons, has never reached this percentage, even after all the turbines were installed in 2019. According to data from the National Electric System Operator, the plant came closest to reaching this efficiency in 2022, when it recorded a capacity factor of 37.8%. In 2024, a year of extreme drought in the Amazon, Belo Monte’s capacity factor fell to 23%—less than half the average for Brazilian hydroelectric plants and 17 points below its expected performance.

InfogrAPHIC: Rodolfo Almeida/SUMAÚMA

Ricardo Baitelo has a PhD in energy planning and is now project manager at the Brazilian non-profit Instituto de Energia e Meio Ambiente. He compares this energy yield with yields from wind power plants, which are also fickle because they depend on variable winds but today average 40% efficiency in Brazil’s South and Southeast and 47% in the Northeast. “During the debate over Belo Monte, what I and many others argued was that wind and biomass energy would be better for the system at that point in time,” says Baitelo. “We always warned that Belo Monte was unfeasible,” says agricultural engineer Danicley Saraiva de Aguiar, a specialist in regional planning and development at the Federal University of Pará and senior forest campaigner for Greenpeace Brazil. “We spent 40 billion reais [USD 7 billion] on a hydroplant that now needs another reservoir.”

Plans from the early 1980s, inherited from the dictatorship and predating the 1988 Constitution, envisaged the construction of up to six dams on the Xingu. In 2008 the National Energy Policy Council approved a resolution determining that only one dam would be built, which was seen as a strategy to secure approval of Belo Monte. Purportedly to minimize social and environmental damage and avoid flooding Indigenous lands, the Belo Monte project opted for a run-of-the-river hydroelectric power station without a large accumulation reservoir. This isn’t an unusual option: Itaipu, on the Paraná River, is also considered a run-of-the-river dam system, although it has a reservoir of 1,350 square kilometers to increase the force of the falling water. At Belo Monte, generation varies according to river flow and its two reservoirs, which, though “small” for a hydroelectric plant, constitute an immense environmental tragedy, totaling almost 500 square kilometers. It is from these reservoirs that the water diverted from the Volta Grande do Xingu is directed to the turbines.

Although the project called for a run-of-the-river facility, the problem is that its power generation potential was designed to be more than 11,000 megawatts, although capacities of 5,500 to 7,500 megawatts had been considered. That’s why the report by the panel of experts predicted that, if built, the hydropower complex would be headed for a “planned crisis”: when it came onstream, the gap between the potential of the installed turbines and the electricity they actually produced would “suddenly be discovered.”

Aerial view of Belo Monte dam and hydroplant: Brazil’s current goal shouldn’t be a new dam but better use of the energy it produces. Photo: Carlos Fabal/AFP

It has been more than 166 days since the meeting in Brasilia where Norte Energia brought up the proposal for a new reservoir, but nothing has been presented to Ibama. SUMAÚMA lodged another request through the Access to Information Law, and the environmental agency replied, “the environmental licensing administrative process for [the] Belo Monte [hydroelectric power plant] contains no documents on the project […] or on the intention to build it in.” SUMAÚMA ascertained that the idea of building a new reservoir came as a surprise to Ibama—it had never been mentioned in dozens of meetings between the Belo Monte management company and the environmental agency. The press office of the mines and energy ministry told SUMAÚMA that “there was no formal communication on the matter after the aforementioned meeting.” The same thing was said in response to a request via the Access to Information Law.

Sources SUMAÚMA spoke with in Brasilia do not rule out the possibility that the new reservoir is a “bargaining chip”—a proposal made to be withdrawn in exchange for what Norte Energia has always wanted: to use a water management plan for the Xingu that would be more advantageous for electricity production but considered deadly to the Volta Grande ecosystem since it would remove much more water from the river. The company calls this plan a “consensus hydrograph,” alternating between the hydrographs known as “A” and “B.” However, the idea of alternating between the two was never authorized because, as an Ibama technical report from October 2024 explains, it would cause “impacts of a magnitude greater than those foreseen in the Environmental Impact Assessment” and would not be “safe for the maintenance of biodiversity and the way of life of the peoples of the Volta Grande do Xingu.” Instead, only hydrograph B has been implemented. Even so, as its effects have not been mitigated to their satisfaction, the environmental agency’s experts state in their October report that it is “essential and urgent to conduct studies to enable the definition of a less damaging and more sustainable hydrograph (or set of hydrographs) for the Volta Grande do Xingu.”

SUMAÚMA asked Ibama about the water management plan and whether the agency endorses the environmental experts’ conclusion. “This is a matter of utmost importance that requires extensive discussions involving other parties beyond Ibama and is currently under analysis,” said the agency.

Although it produces less energy than expected at the time of its construction, Belo Monte has become an important part of Brazil’s interconnected power system, or SIN, made up of thousands of different types of power plants. However, its contribution is irregular. Between 2019 and 2024, the average energy generated by the dam on the Xingu as a proportion of the average generation for the entire SIN grid has varied from a low of 3.22% in 2024 to a high of 6.04% in 2022, a year when Itaipu’s contribution was 8.5%.

Since Belo Monte’s construction, however, the characteristics of the Brazilian electrical grid have changed. At the beginning of the century, solar, wind, and sugarcane-bagasse power represented only 2% of the SIN grid. Now wind, solar, and biomass account for 28% of the SIN’s current installed capacity. So the big goal today shouldn’t be to build a new reservoir at Belo Monte—with all its ensuing environmental and social impacts—but to make better and more efficient use of energy generated by these new sources.

Boys scale a tree in an area flooded by the Xingu: the hydroplant has displaced more than 20,000 people. Photo: Aaron Vincent Elkaim/The Alexia Foundation

WHAT NORTE ENERGIA SAYS

All reports, information, and findings on the impacts of Belo Monte gathered by SUMAÚMA were sent to Norte Energia for comment. The company received the list of questions [8] at 1 p.m. on Friday, May 7, and was given 48 business hours to answer. Norte Energia asked for more time to respond, and SUMAÚMA agreed. Additional questions were sent on Wednesday, May 14, and Thursday, May 15. In the early evening of May 15, Isabele Rangel, head of Norte Energia’s press office, phoned SUMAÚMA to say that no questions would be answered. A few days earlier, the company had sent a note stating that the questions “carried value judgments and made assumptions with which Norte Energia does not agree” and that they “cannot serve as a starting point for what is meant to be a balanced and open dialog between the company and SUMAÚMA.”

SUMAÚMA also asked Folha de S.Paulo why Ibama, the federal Public Prosecutor’s Office, or the voices of those affected by Belo Monte were not given space in the news story resulting from Norte Energia’s invitation. The newspaper’s managing editor, Vinicius Mota, replied that “conditions for accepting travel invitations from third parties are set out in the Editorial Manual, in the ‘Conduct’ section, and were observed in the case in question.” The text, available online, reads as follows: “When producing content resulting from an invitation, the professional must maintain independence and a critical attitude.”

In a written response sent to SUMAÚMA, Ibama said, “the review of the project’s operational license is ongoing,” and a technical review from 2024 “identified pending issues still to be addressed prior to renewal.”

When asked by email on May 12 and 13 about Belo Monte’s environmental licensing requirements that are affecting social and health issues in Altamira, the municipality did not respond.

Landscape of death: withered trees dot the Belo Monte reservoir on the Xingu River. Photo: Pablo Albarenga / Sumaúma

Report and text: Claudia Antunes, Fernanda da Escóssia, Malu Delgado, Rafael Moro Martins, Soll and Plinio Lopes

Editing: Talita Bedinelli

Art Editor: Cacao Sousa

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Spanish translation: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Diane Whitty and Maria Evans

Infographics: Rodolfo Almeida

Copyediting and finishing: Natália Chagas

Editorial workflow: Viviane Zandonadi

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum