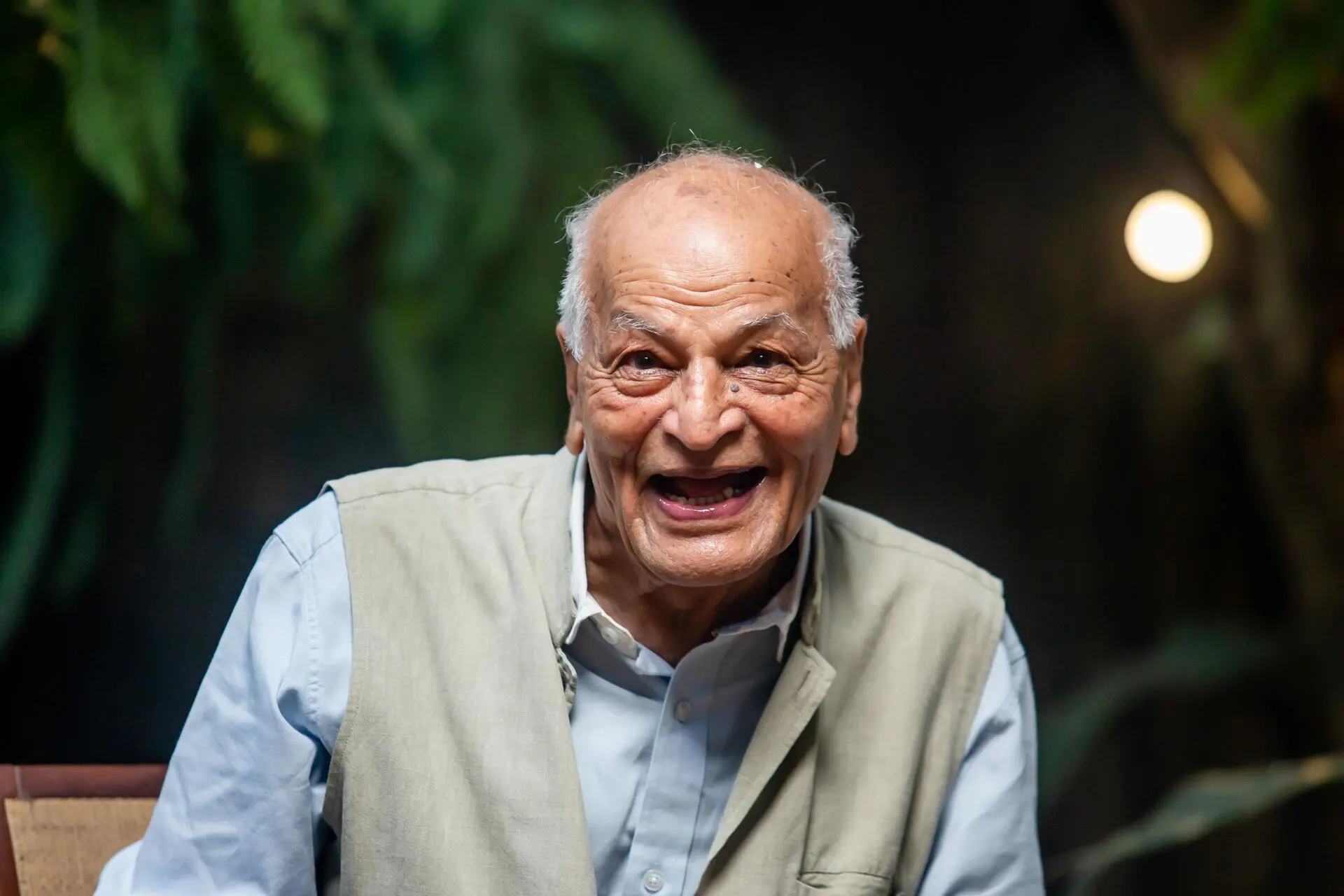

“It’s so green!” Satish Kumar is surprised when he sees the trees and plants in the backyard of his Brazilian friends’ home in the Alto de Pinheiros neighborhood of São Paulo—rare foliage flourishing amid the city’s concrete monocrop. With his slow, easy steps, Satish’s gentle footfall reflects his distinct brand of activism: Activism with love. The former Jain monk, born in Rajasthan, India, tilts his head slightly to the right, perhaps under the weight of his 87 years. Or maybe this is how a body bends when it has learned by long experience how to listen. In the patio garden, surrounded by a huge Pitanga tree, one Golden and one Pink Trumpet tree, a somewhat twisted Mignonette, some Raffia palms, and a mature Schefflera, the activist who preaches radical love joins 14 young Brazilian activists to share experiences and talk about daily resistance. These youth want to learn from Satish’s long journey.

Climate-concerned, Black, Indigenous, feminist, antiracist, residents of Brazil’s marginalized urban peripheries—the young activists settle somewhat timidly, into a circle in the green backyard. In a circle, the energy flows. The topic of the conversation is manifestly complex. After all, how can you ask these youth to act out of love if their lives and the lives of their families and communities are battered day after day, their bodies relentlessly violated, their homes destroyed, their territories taken, while Nature is in extreme distress, death is on the prowl, injustice reigns, and impunity persists? How can they control their hurt and anger? How can they help but feel hatred toward those who want to erase them and make them invisible? Satish, co-founder of Schumacher College, in Devon county, England, believes he knows how. He came to Brazil to celebrate the tenth anniversary of a branch of the college here and to launch Amor Radical, the Portuguese translation of his latest book, a summary of the kind of activism and way of life that he believes can save the planet and humanity. He made time in his schedule to devote an afternoon to the young Brazilian activists.

To welcome everyone and set the scene for the conversation, Wajã Xipai, an 18-year-old Indigenous man, sings a song of the Xipai people from the Middle Xingu. The song “Wïra na Iko” summons the forest spirits and asks them to remain among the group. During the ancestral prayer, everyone taps their feet on the ground. Everyone is connected. Ears and hearts open. Wajã traveled from the Xipaya Indigenous Territory in the Amazon to close out a year-long cycle of the Mycelium-SUMAÚMA Forest-Journalist Co-Training Program. Singing in his mother tongue, he makes music his opening message, while every three minutes an airliner en route to Congonhas Airport, which receives 70,000 passengers a day, drowns out the backyard birdsong.

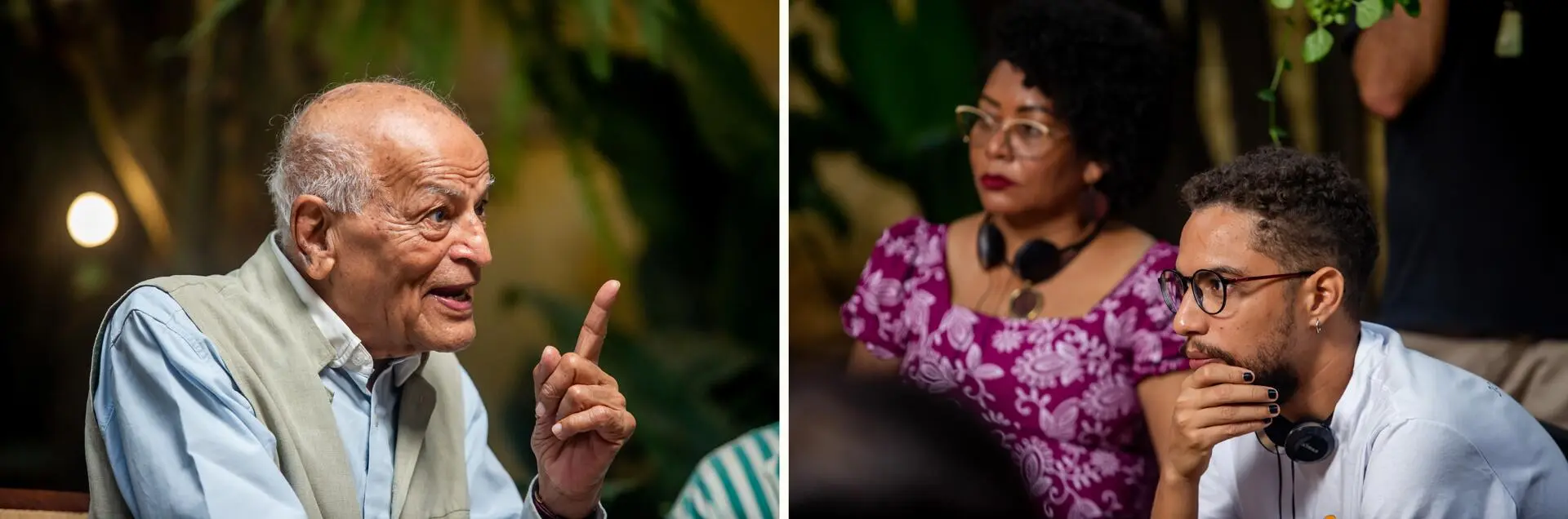

Affection and hope: Soll, a forest-journalist who took part in the Mycelium-SUMAÚMA program, thanks Satish for his wise words and encouragement

Old time, new time

After Wajã comes 30-year-old Thiago Henrique, or Karai Djekupe, a leader of the M’bya Guarani people from the Jaraguá Indigenous Territory in São Paulo state. Thiago, who holds a degree in architecture and urban planning, leaves it clear that his Indigenous name is sacred: “It comes from other worlds, from spirituality.” He says that understanding the importance of an Indigenous name means understanding time. “Unlike non-Indigenous people, we don’t have spring, summer, winter, fall. We have Ara Ymã [old time] and Ara Pyau [new time],” Karai Djekupe says. “Ara Ymã is old time, when diseases tend to catch people more. This is the time we’re in now, when Nature needs to take care of itself. And Ara Pyau is when the weather gets warmer, more floral, when we’re able to do more, when our spirituality blossoms and we receive our Guarani name in ceremonies, given to us after we turn one year old.”

The Guarani, Djekupe tells the group, have never felt they own Nature. He talks about his people’s historical resistance and remembers the 18th-century Guarani wars and massacres by bands of adventurers and fortune seekers known as bandeirantes, who founded São Paulo at the cost of Indigenous lives. “Even though the colonizer tried to eradicate our languages, eradicate our customs, and colonize our bodies, we can affirm that they didn’t colonize our souls. We do our ceremonies; our Ara Pyau is always reborn.”

Karai Djekupe tells his colleagues and Satish that the Indigenous peoples of Brazil will once again be evicted from the few territories they have managed to demarcate, all because of the Marco Temporal (historic cutoff thesis), which is, in his words, “the idea non-Indigenous people have of setting a cutoff date, October 5, 1988, to define Indigenous communities’ right to land.” The young activist says it is unacceptable for Brazil to swallow this perverse idea, considering that Indigenous people were either massacred by the colonizers or placed under the tutelage of the business-military dictatorship (1964-1985). Since colonization, violence against Indigenous people has been “linear, continuous,” he says. “Those who kill us then hold their own trials, find themselves innocent, and go back to legitimizing all of these massacres. Human rights don’t extend to us. Today we’re fighting for democracy in the overall context of the nation. But we, Indigenous peoples, have been waiting ever since 1500 to see this democracy.” The Guarani refuse to accept this war, Djekupe says. “We believe dialogue and union among all of the people who are fighting can ensure our children’s future.”

Satish listens with a penetrating gaze. The young people are then invited to tell how they became activists. “I come from the periphery of Altamira [Pará]. We have a relationship of belonging with our rivers and streams, bathing in them, gathering in community, playing and learning. After they built the dam [for the Belo Monte Hydroelectric Power Plant], the population swelled, and there were tremendous environmental and social impacts, and these spaces of belonging were destroyed,” says Soll, 28, a visual artist, former participant in the Mycelium program, and now a reporter for SUMAÚMA. Soll says “art and love” are his tools for fighting. After the dam was put in, the river “turned into a strange lake,” teeming with “rotten trees.” “Many people were torn from their lands to distant places. At the time, I felt I was losing really important things. I saw the memory of my people and my community at risk. So that’s what motivated and moved me,” Soll says.

Empathetic listening: Bruninho Souza (left), Satish, and Mathaus Torres during a firm yet gentle conversation with Brazilian activist youth about radical love

Cleidiane Carvalho, 42, isn’t as young as the others in the circle but, like them, she joined the struggle at an early age. She begins by reciting a poem she has just jotted down in a small notebook in her hands:

Different faces, all on the same quest

The environment must be felt

To fight and resist is to offer those who aren’t here yet

the green era that others don’t want to leave standing

How ignorant these mere men who use their very strength to destroy the world they live in

Clei, a nurse who is also with the Mycelium-SUMAÚMA program, worked with the Munduruku people, in Pará state, for 16 years. “What made me want to be an activist was when I entered the first illegal mining area in the region of São José, in Jacareacanga [Pará]. I had never seen a child who had suffered pedophilia. I tended to a 6-year-old with marks all over her. In my innocence, I asked, ‘What kind of horseplay was this?’ And they told me, ‘No, nurse, this child was raped; her mother sells her to old men in this mining camp.’ That really hit me. I couldn’t speak. There was nothing to say, because if we said anything, our lives would be threatened.”

Clei did what she could. She went to the authorities, reported the abuse and violence, denounced injustices. A few years ago, she was the first healthcare professional to warn about the effects of mercury poisoning among the Munduruku people. “I contacted the Health Ministry at the time, but who was I? Just a nurse, Black and voiceless.” In 2019, with the assistance of staff from Fiocruz, a federal medical research foundation, she entered the Middle Tapajós territory: “It was found that more than 90% of the women and children had high levels of mercury contamination.” The expedition resulted in the book Garimpo de Ouro na Amazônia: Crime, Contaminação e Morte (Gold mining in the Amazon: crime, contamination, and death) and was the inspiration for the documentary The Amazon, a New Minamata?, directed by Jorge Bodanzky. Some years later, it also awakened Brazilian healthcare teams and the federal government to the tragedy. “I felt this desire to record events through photos and writing, but not show myself. Other people spoke, using my material and collections; they could show the world this massacre, this crime. I decided I needed to do something as a nurse, as a woman, as part of the resistance.”

Almost half an hour after the meeting has begun, Satish speaks. All eyes are on him, as the jets continue their infernal noise. “We can be activists against noise. This airport is bothering so many people in São Paulo!” he jokes. But his calm isn’t shaken by the noise pollution. Coincidentally, the birds make a commotion when Satish begins. A leaf falls near his head. Satish says he became a Jain monk when he was nine. He had lost his father suddenly, at the age of 4. He opted for the religious life in a spiritual attempt to deal with death. But when he was 18, he had a disturbing dream about Mahatma Gandhi, assassinated in 1948. In his dream, the activist and worldwide symbol of India’s struggle for independence told Satish the world needed fighters and it wasn’t enough to withdraw into monastic life in search of spiritual salvation. “I said: ‘Wow, Gandhi calling me to be an activist! The world isn’t good. I must die for the world.’ After midnight, when all the monks were asleep, I ran away from the monastery.”

Choosing words: under the watchful gaze of Soll and Cleidiane, Satish tells the activists they must learn how to communicate their ideas

‘What legacy will we leave behind?’

For ten years, Satish went from village to village in India, trying to raise landowner awareness about the country’s extreme land concentration and the poverty and exploitation suffered by its workers. In the company of Vinoba Bhave, his guru and Gandhi’s spiritual successor, Satish traveled his country under the slogan “Wealth and land should belong to everyone.” The activist dedicated his latest book to the guru. As a result of this pilgrimage, social pressure mounted for land reform in India, and 4 million acres of property owned by large landowners was redistributed to poor Indians.

Satish’s subsequent struggle was against nuclear weapons, in the 1960s. “People had no land, no food, and they [world powers] were spending money on bombs,” he tells the young people. He walked 8,000 miles with no money in his pockets. With nothing. He crossed many countries. In the United states, France, England, and Russia, he protested the bomb. He had the privilege of meeting Martin Luther King, of whom he speaks with love and admiration.

After taking so many steps and waging so many struggles, Satish embraced climate activism: “I got involved in the ecological movement because of the destruction of the environment. We have to learn from Indigenous values, from Indigenous cultures. They have taken care of the planet for millions of years without destroying it,” he says, looking at the Indigenous people sitting in the circle. “What kind of legacy will we leave future generations? Polluted rivers, polluted oceans, polluted air, polluted water, polluted soil? What are we doing to the planet? So I became an activist to defend the environment. Activism against large landholdings, against racism, against nuclear weapons, against war, and against ecological destruction. This has been my activity for many, many years. I’m 87 now. But you have plenty of time,” he says with a smile, trying to prepare the young activists for a very long journey.

Satish says he learned from Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Desmond Tutu, and Nelson Mandela that “activism comes from love.” Speaking firmly yet tenderly, he assures the group that activists don’t act out of hate, fear, or anxiety. “But out of love. Because if you act out of anger, you’ll soon be exhausted, burned out. Anger is hell. You’ll be disappointed and give up. But if you act out of love, love strengthens you, and you keep going.” Satish guarantees he will go on living right through the final battle, without burnout. “Because I’m a happy activist. Do you want to be happy or miserable? It’s up to you.”

The activist leader teaches three pillars to fighting with love: “be the change you want to see in the world; learn to communicate this change and use good tools to communicate your ideas; join together, act collectively. A great movement is made up of many individuals. No single individual will be able to change the world. A river is made of countless small streams. Find common ground.”

Common ground: the Indian activist explains to the Brazilian activists that they can’t change the world alone; rather, collective action is paramount

In Parelheiros, a region in the far south of the municipality of São Paulo, 24-year-old Bruno Souza de Araújo, nickname Bruninho, found common ground with his friends—the ground of the poor urban periphery. It was there, site of “what’s left of the Atlantic Forest in São Paulo,” that Bruninho, who founded the Center for Young Politicians collective, discovered the solution to practicing antiracist activism in literature. “With a group of friends, we opened a library in a very unusual space, in a cemetery. A group of young Black people got together to build a community library in a place where people were expecting other things. This sends a lot of messages in a country where the Black population is suffering genocide.”

Resignifying a place associated with death, associating it instead with life and literature, in a country where 77 out of every 100 murder victims are Black, is a way of turning to words to describe feelings on the periphery, Bruninho tells the group. “Sometimes it’s not only food, water, school, and a good education that are missing. Sometimes what’s missing are words to describe the world we live in, the things we feel and the community we’ve built.” Bruninho looks to Satish for answers: “What words and solutions should we, activists, use in our daily lives so we can continue existing and resisting? What other words are there to build possible futures?”

“You have to be realistic and prepared for suffering,” Satish replies. “Martin Luther King was arrested 29 times,” he points out, “in more than a decade of activism.” He goes on: “Jesus Christ was nailed to a cross. Change will come, but only when conditions allow it, and consciousness is reached collectively. Martin Luther King could never have imagined Barack Obama as president of the United States.” Satish asks the young activists to have patience and courage.

Climate activist Amanda Costa, 27, says she feels her heart on fire while listening to Satish. A resident of Brasilândia, on the north side of São Paulo, she is one of the founders of Sustainable Periphery, a not-for-profit organization that promotes sustainable educational actions in marginalized neighborhoods. “Activism wasn’t a choice for me; it was a calling. On my journey, I’ve felt a lot of anger in my heart. But, as you said, we have choices.” Amanda wants to know how Satish chose love at moments of fear and injustice. “What pathways made this conscious choice possible, so you, at 87, are able to communicate with passion and vitality?” the young woman asks.

Looking at Amanda, Satish tells her he views problems as opportunities. “I don’t complain, even if it’s very hard. I think I have to communicate better, do things better. Activism can be through music, through protest, through art—many forms. But you have to be clear and strong. To change biases and minds, you need good arguments, good examples, and good communication to persuade people.” Amanda asks more: “And what is love to you?” Satish replies: “It’s loving unconditionally, despite reality, despite yourself, despite Nature, despite people. Without any demands. Accepting yourself as you are, accepting people as they are, in true dialogue, true communication. It’s accepting even what’s bad; accepting the reality of life.”

River of feelings: in the conversational circle with Satish, two Guarani youth, Thiago and Suzana, talk about the pain of Indigenous peoples

Love, the missing word

Mateus Fernandes, 23, a climate activist and antiracist raised on the poor outskirts of Guarulhos, in Greater São Paulo, couldn’t figure out the word love. “For a long time, the word ‘love’ wasn’t part of my existence, in the sense of affection, of upbringing. Racism destroys many things. We don’t have the privilege of staying strong.” Mateus says activism left him ill. “Climate activism came into my life with the role of healing. If I didn’t think things could get better, I wouldn’t get out of bed. Violence was imminent, but my activism remained strong. One favela alone doesn’t move everything, but a collection of peripheries—look at the power we have,” he says.

Satish is delighted with Mateus’s healing: “If you’re a climate activist, an Indigenous activist, a social activist, I often say that when you’re working together, with other people, you find your place within the whole. Different people choose different paths. There are countless forms of activism, but working in solidarity, in friendship—that’s what makes for joyful activism.”

Pain and love always come together, Satish says, and activism demands optimism: “When we see suffering, death, and violence, we feel pain. And feeling pain is good because it’s a sign that your heart is alive.”

As the conversation draws to a close, the group appears to have formed a deep connection with Satish and his teachings. “Each one of us is like a seed with the potential to become a tree. But how does a seed turn into a tree? Through relationships. Without soil or water, the seed can’t become a tree. And it has to have sun. Without sunlight, the seed can’t turn into a tree. I can’t exist alone. I can only exist with other people.”

Satish thanks the young activists for the exchange. He tells them they will become trees. “Love can transform the ordinary into the extraordinary. Love each other, love people, love Nature, love every moment of your life,” he says. Everyone seems much lighter in spirit. It’s even possible to ignore the annoying roar of the planes overhead.

Mycelium: Soll, Natalha, Wajã, and Cleidiane (left to right), forest-journalists with the SUMAÚMA program, shared the joy of listening to and learning from Satish

Report and text: Malu Delgado

Editing: Talita Bedinelli

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Spanish translation: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Diane Whitty

Copyediting and finishing: Natália Chagas

Editorial workflow coordination: Viviane Zandonadi

News editor: Malu Delgado

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum