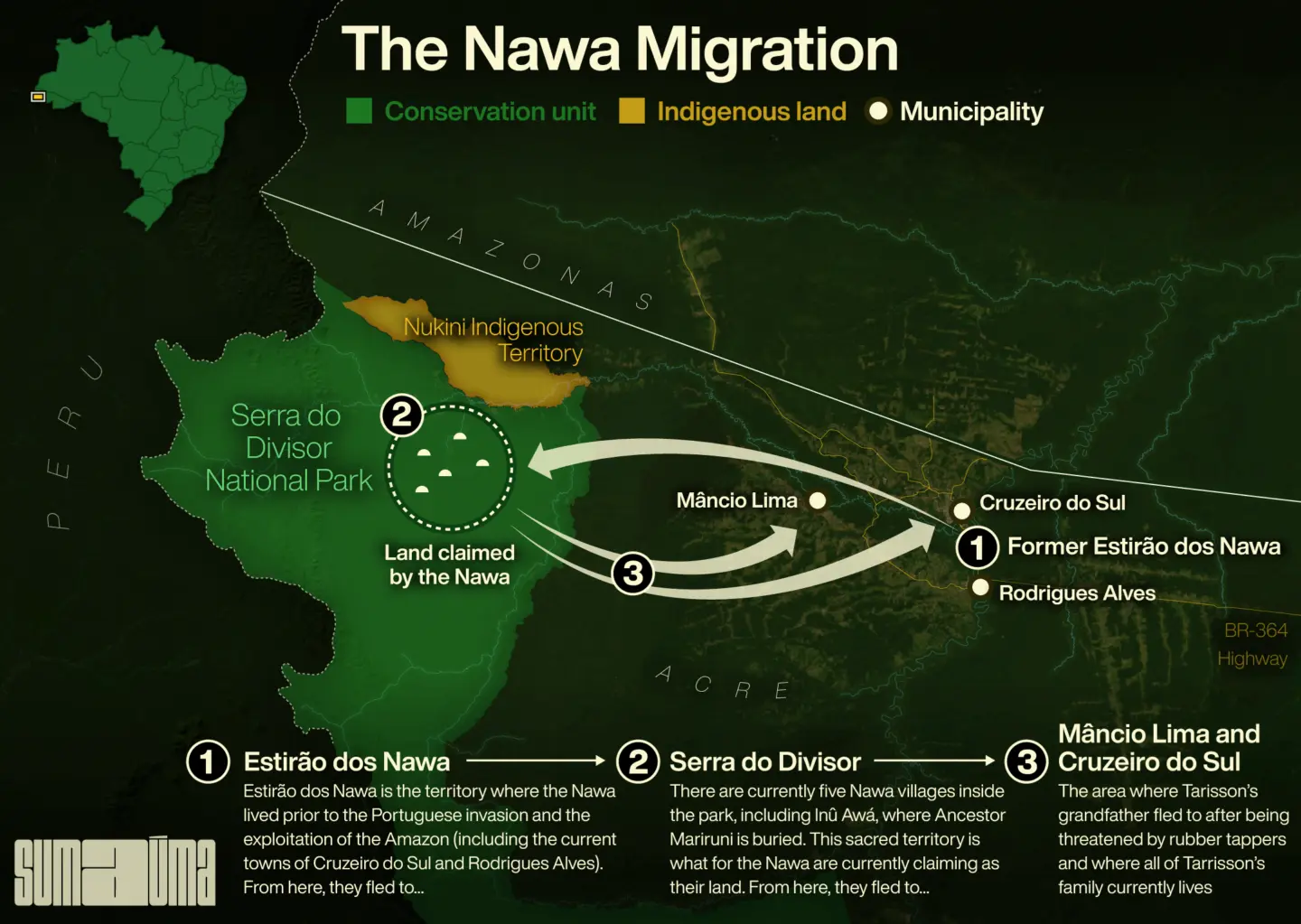

Tarisson Nawa was just three years old when his people began organizing in 1999 to gain recognition of the territory in Acre where his ancestors had lived along the border between Brazil and Peru. Now almost 25 years later, they have yet to see demarcation of the area encircled by the Novo Recreio Tributary and its dark waters that flow into the Moa River.

The Nawa, persecuted and expelled from their lands for centuries, ended up corralled by the Brazilian State. In 1989, the area where part of their ancestors had lived was designated the Serra do Divisor National Park, a restricted-use conservation unit that does not allow for human habitation, not even by those who have lived there for generations in harmony with the forest. The Nawa, spread across various areas of the state but with some families still living inside parklands and being pressured to leave, began to organize and demand territorial demarcation. They found themselves trapped in a legal dispute that has now been going on for decades.

Last year, Tarisson, who became an anthropologist, was invited by the National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples (Funai) to resume discussions about the future of the territory following years of inaction. Feeling encouraged, he joined one of the foundation’s working groups as an assistant collaborator; he traveled to the land of his ancestors and helped conduct new studies of his people. But once again, his relatives were thwarted. Funai has not kept its promise to release an updated anthropological report on the demarcation process by September 2023. Nothing can move forward without that document. When questioned by SUMAÚMA about the delay in demarcation, the foundation did not respond.

Tarisson recognizes the case of the Nawa is extremely complex, primarily because its members have spread across different regions of the Amazon over the centuries and have been victims of systemic erasure. “In the past, we were the Kapanawa and inhabited the region that today includes [the municipality of] Cruzeiro do Sul, the so-called Estirão dos Nawa,” he explains.

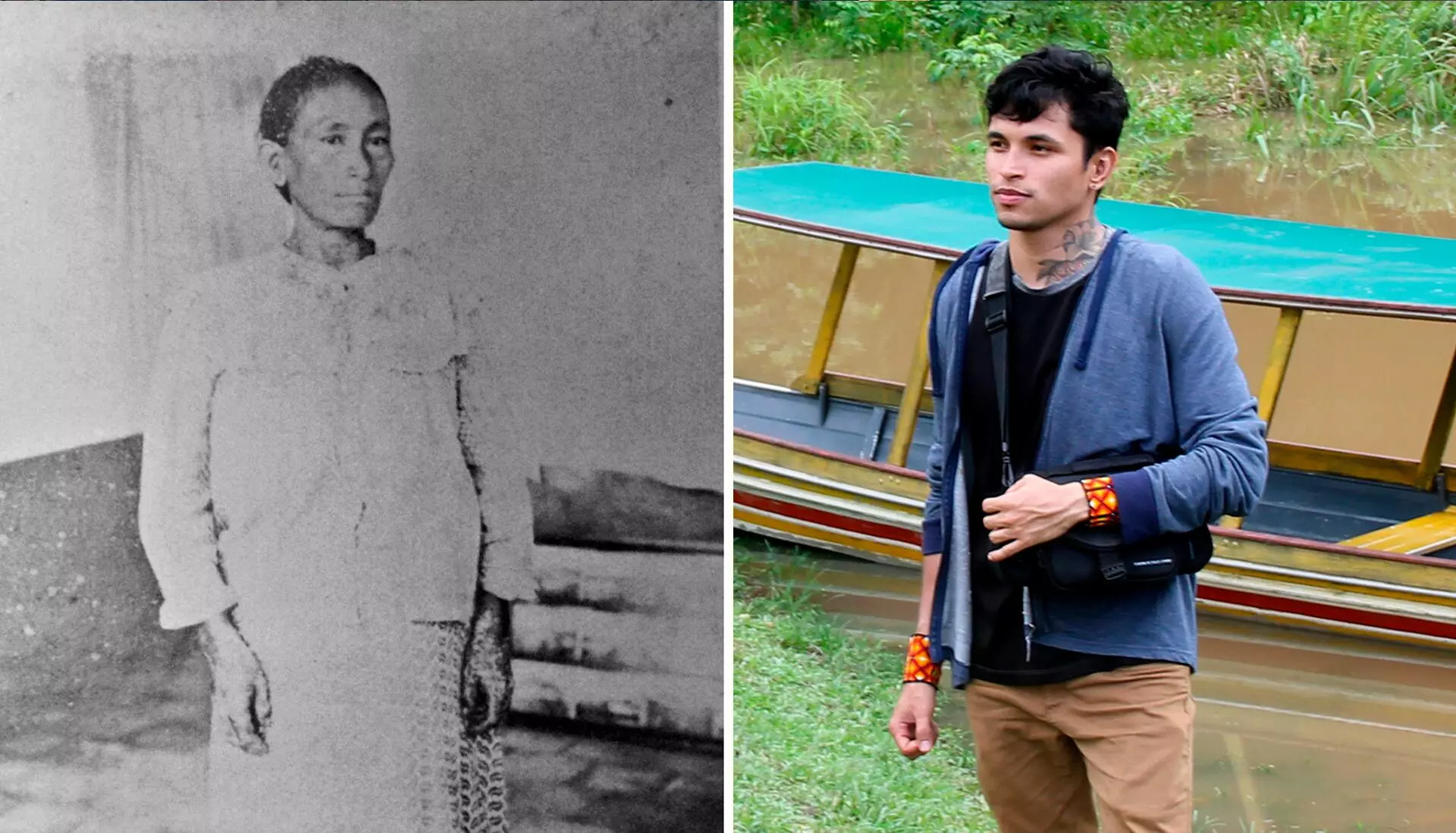

Back in the 19th century, Mariana [Mariruni], listed in historical records as the last survivor of the Kapanawa, migrated from Estirão dos Nawa to the region where the Serra do Divisor National Park lies today. In 2017, Tarisson began researching the history of Mariruni, whose name means “bush agouti” in Pano, a language in the Nawa language family. Mariana was her Christian name. She was his great-great-grandmother, the ancestor of his people. “I was brought up without knowing I was Nawa,” he says. The anthropologist explains the gradual shift from using the name Kapanawa to the name Nawa in Mariruni’s lifetime. “At the time, my people were Kapanawa. And we called everything that wasn’t Kapanawa – Nawa, which means ‘other’ [otherness]. For us, a white person was Nawa.” Yet as white people began coming into steady contact with the Indigenous Kapanawa, they began to refer to the Kapanawa as Nawa simply because that was the word they kept hearing over and over.

Mariruni (left), the last Kapanawa Indigenous person and great-great grandmother to Tarisson (right). Photos: Alma Acreana/Personal archive

The Nawa say that Mariruni managed to escape persecution by European rubber tappers and successive violent colonizers. Yet on one of her escapes down the Juruá River, she wound up imprisoned at the behest of Sinhá Geton, a rubber baron whose past is a mystery. There are two versions to Mariruni’s recollection, which was gleaned from oral history, neither with precise dates. The prevailing version states she was alone when arrested; in the other version, she was with a brother. Mariuna was subordinated by white people, imprisoned on rubber plantations, and ultimately married José Peba, who worked for Sinhá Geton. After the two wed, they went to live in the area that now constitutes the national park. The Nawa say that Mariruni and Peba had eight children. Mariruni, survivor, progenitor of the Nawa, was buried in the territory-turned-park, which is why Tarisson’s relatives consider it sacred and ancestral land.

“That is where the Nawa of today come from,” explains the anthropologist who dedicated his master’s thesis in social anthropology entitled “The Nawa Were Never Extinct” to his great-great-grandmother. Years earlier, as an undergraduate student of journalism at the Federal University of Pernambuco, Tarisson had already started delving into his ancestry. His undergraduate research project was a documentary entitled “Memórias Nawa: das malocas ao contexto urbano” (Nawa Memories; From Malocas (Indigenous Cabanas) to the City).

It is precisely the territory where Mariruni lived, where the Serra do Divisor National Park stands today, that the Nawa are claiming in the ongoing demarcation process. Some Nawa still live inside the park, but many of the descendants who have married non-Indigenous people are scattered across several other towns and cities in Acre. The Nawa migration across the state was also the result of numerous attempts to escape both violent rubber barons who had imposed a new form of slavery on the Nawa and agricultural encroachment into the Amazon forest.

Historical records point to a Nawa presence in the Alto Juruá region dating back to the 19th century. But it’s no secret the territory had been occupied by Indigenous peoples long before the arrival of the Portuguese in 1500. Invasions in the region by European settlers came in waves, with incursions during the 19th century rubber boom considered some of the bloodiest of all time. It was during this extremely violent period when Mariruni so bravely resisted.

The state had once considered the Nawa extinct. Funai anthropological reports from the 1970s and 1980s point to the existence of Indigenous peoples in the Upper Juruá and Novo Recreio Tributary (Mariruni’s territory), but list them as Nukini. For the white people, the Nawa had disappeared; for the Nawa, never. For centuries they had inhabited the territory, yet for centuries they remained silent, afraid to reveal their identity. The Nukini managed to get their territory demarcated in 1991. “I was born at a time when my people still didn’t have the courage to say who they were,” Tarisson recalls.

The descendants of Mariruni, the ‘bush agouti’

Branches were added to the family tree following Mariruni’s marriage, but the Nawa continued to face persecution, assassination and compulsory, backbreaking work on rubber plantations and extractive farms. And the migrations continued. Tarisson’s grandfather, Francisco Ferreira da Costa (Chico Peba), was born in the territory that would eventually become the park. In the early 1980s, a rubber tapper and his henchmen threatened Chico Peba with machetes and rifles, forcing him to flee the area. Tarisson says his grandfather wanted never again to return.

“My grandfather had eight children and was so afraid of dying he decided to leave. He left the territory in the park we are now claiming and went to the rural outskirts of a town called Mâncio Lima. He bought a large plot of land where my family lives to this day.” And Tarisson’s relatives preserved Nawa traditional customs; they lived, hunted and fished along the banks of a stream.

The anthropologist’s relatives settled in a rural neighborhood known as Estirão do São Domingo. “That’s where my family is. But today there are Nawa families inside the village [in the park], in Cruzeiro do Sul [the ancestral territory, formerly known as Estirão dos Nawa], in many places, and also in Estirão de São Domingo.”

The same story of escapes played out with the family of Cacique Railson Nawa, who has been fighting for recognition of Nawa territory within the park for over a decade. “My grandmothers fled to the headwaters of the Azul River by way of Novo Recreio [tributary] and then stayed in that region,” the cacique recalled.

Cacique Railson Nawa awaits demarcation: ‘We are the sons and grandsons of those who resisted; we fight for the lands of our ancestors.’ Photo: Alexandre Cruz Noronha/Amazônia Real

At age 27, Tarisson spent 15 days with a team from Funai visiting his relatives’ villages to collect testimonies and data to buttress the Detailed Identification and Delimitation Report. Yet six months past the date set by Funai, the document, which is essential to demarcate the territory, has yet to be published.

“If this report isn’t delivered, there’s a chance leaders will start demanding that the demarcation process be brought before the courts. The process of demarcating our territory has been stalled for decades. This is just an outright violation,” Tarisson says.

According to the Nawa people, five indigenous villages currently fall within park borders: Novo Recreio, Sete de Setembro, Jezumira, Boca Tapada and Inû Awá. In 1998, when the Brazilian Institute for the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (Ibama) and environmental NGOs conducted a census to survey the population inside the park, it found 522 families living in the area.

Aerial view of where the Nawa live inside the Serra do Divisor National Park; the Novo Recreio is the name of both the tributary and the village. Photo: Alexandre Cruz Noronha/Amazônia Real

And midway through, a park appears

The park, which measures 2.08 acres (8,400 square kilometers) is recognized as one of the most biodiverse areas in the Amazon. Its creation made the Nawa realize that if they didn’t fight to remain within the park’s borders, they would be swallowed up by what they call “environmentalism without people.” For this Indigenous group, this type of environmentalism sees only the forest, not the people who inhabit it. And, to add insult to injury, not once were the Nawa consulted about the creation of the conservation unit.

It was during a visit from the Indigenous Missionary Council (Cimi) to the Moa River in 1999, ten years after the park’s creation, when an Indigenous woman broke the silence. Dona Chica do Celso, Tarisson’s great-grandfather’s niece and heir to the Mariruni legacy, came out as Nawa. At the time, Brazilian environmental agencies were finalizing a management plan for the park, and the federal government had begun registering the Indigenous and non-Indigenous people it was planning to displace.

When the Nawa realized the government was attempting to remove them from their ancestral lands, they reached out to Funai. In 2002, an anthropological report published by Funai recognized the Nawa as a case of “ethnogenesis,” a population that had been massacred in the past, taken on other identities, and was now once again affirming its identity as an Indigenous group.

Dona Chica do Celso, Tarisson’s great grandfather’s niece, died in 2002 without ever seeing official recognition of Nawa lands. She related Mariruni’s stories to the anthropologist. Photo: Liliane Cruz/Personal archive

And that’s when the most recent tug of war began, whereby Ibama started to question the Nawa’s self-identification. According to the Brazilian Constitution and Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization, it is up to indigenous peoples to self-declare, to establish whether they are Indigenous, and to state to which group and community they pertain. Ever since the Nawa began claiming their identity, recognition of Indigenous lands has been hindered by lengthy bureaucratic, administrative and legal fights, with allegations of overlapping areas, conflicting land interests, a tangle of legal disputes and, above all, conflicting views among the federal agencies about how the territory should be preserved.

The Nawa never accepted the government agencies’ proposal to remove them from the park and put them in a settlement.

They chose to remain in the park, resist and fight for demarcation. As for the non-Indigenous invaders who also live within the park, Tarisson explains, they are waiting for the demarcation process to unfold because, once that happens, the government is legally bound to compensate them for any subsequent displacement. According to the anthropologist, conflicts are expected to flare up in the near future as long as the demarcation process drags on.

The Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation (ICMBio), which is responsible for managing federal conservation units, told SUMAÚMA that, since 1989, when the Serra do Divisor National Park was created, “families have been resettled on an optional basis, whenever they have expressed such an interest.” Some residents accepted the proposal to leave the park, according to ICMBio, while others remained or returned years later, “with no resettlement records of indigenous Nawa.” The agency added, “the institute is currently drawing up the Term of Commitment to guarantee the Nawa’s territorial rights.” This document recognizes the rights of the Nawa while they await demarcation.

Neither Funai nor Ibama responded to our requests to comment on the current number of residents in the park or the displacement and removals that have taken place over nearly two decades.

The first studies to identify and demarcate Nawa Indigenous lands officially began in 2003, according to Funai. However, it wasn’t until April 2023, twenty years later, that a working group, which includes Tarisson, was set up to finally resume the process of recognizing the Nawa’s land.

Disregard for the lives of the Nawa has spanned several governments. And during the administration of right-wing extremist Jair Bolsonaro (2019-2022), in which the Funai was gutted, all ongoing demarcation processes were suspended. Desperate and hopeless, the Nawa pursued a process of self-demarcation in 2021, during Bolsonaro’s third year in office.

The Nawa began self-demarcating their lands in 2021: ‘The lines it demarcates often don’t represent our notion of territory,’ the Nawa anthropologist says. Photos: Alexandre Cruz Noronha/Amazônia Real and Tarisson Nawa

“Our most important elder, Dona Chica do Celso, the first person to say ‘we are Nawa’ and the first person to organize our collective fight, died in 2022. This is very sad because she never saw her territory demarcated. It’s distressing to see how tired my leaders are, to see them aging. Yet I, girded with the spirit of youth, believe it is still possible,” Tarisson says.

Cacique Railson says the Serra do Divisor National Park was built atop Nawa lands with the approval of the environmental agencies. That’s why, Railson explains, the Indigenous have historically viewed government institutions as enemies of their people. Now, he continues, the Nawa have agreed to talk to the environmental agencies.

Before there was a park, there were Indigenous peoples…

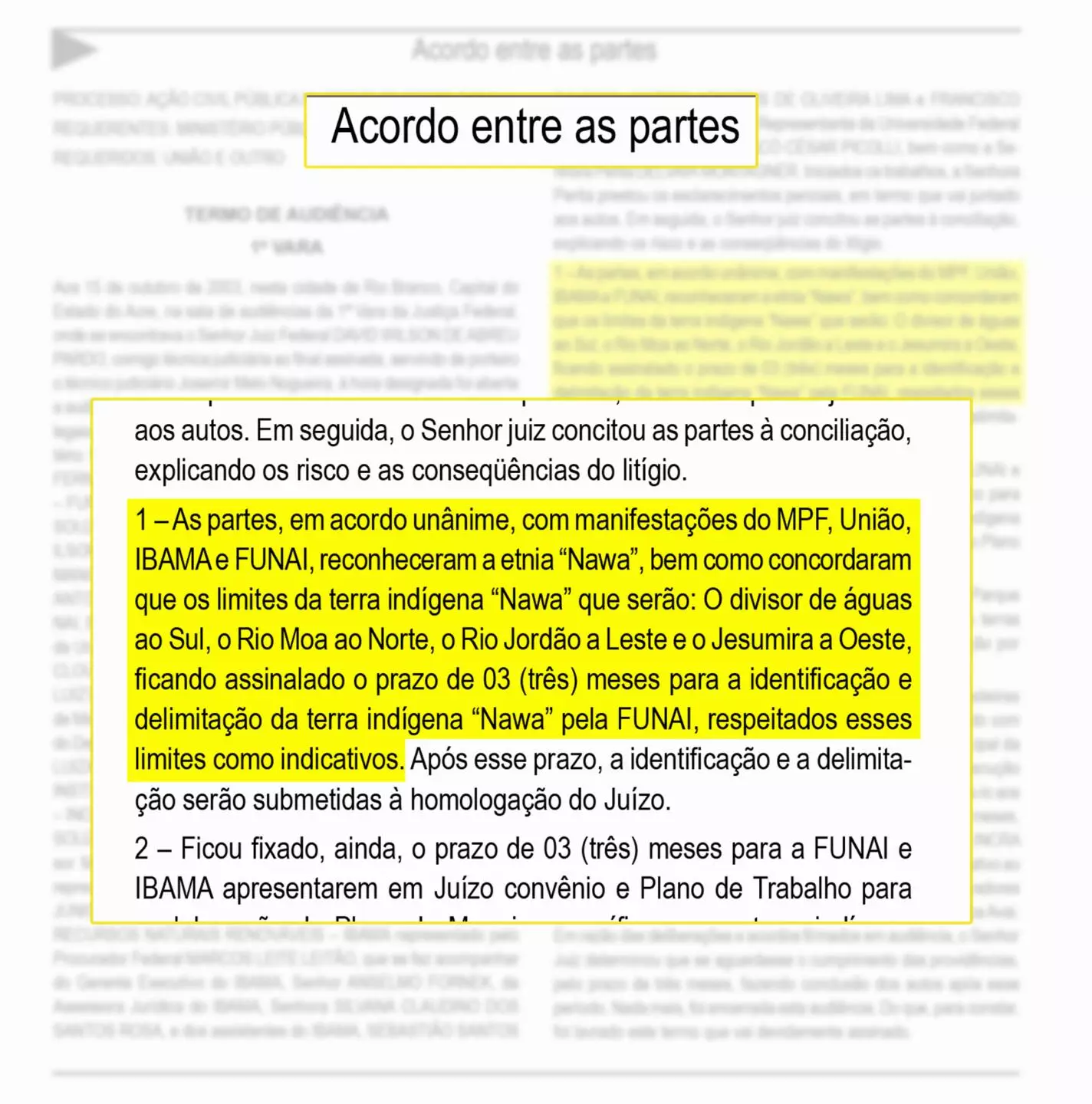

In 2003, the Federal Court of Acre endeavored to reconcile differences between the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office and federal agencies regarding the park area in an attempt to avoid litigation. The aim of the class-action lawsuit filed by the Public Prosecutor’s Office was to ensure the Nawa were heard and included in discussions concerning the park management plan. The parties to the case, which was heard by the First Federal Court, unanimously recognized the Nawa as an Indigenous people, endorsing the anthropological study that Funai had published the previous year. The courts then ordered Funai to conduct an identification and delimitation study of the Nawa territory.

The 2003 agreement signed by Nawa leaders, Ibama, ICMBio and Funai recognizes the presence of Indigenous people in the park. Photo: Reproduction

The following year, in 2004, attorneys for Ibama contested the preliminary Funai report that had delimited 205,636 acres (83,218 hectares), less than 10% of the park’s total area, for the Nawa. The environmental protection agency took the case to the Federal Court of Acre to review the demarcation, claiming the proposed extension of Nawa Indigenous lands would divide the park and could thus jeopardize efforts to preserve biodiversity.

Lucila da Costa Moreira, a Nawa women’s leader, recalls when the Nawa outright rejected Ibama’s opposition to the territory’s boundaries. “[Ibama agents] went around putting [park] signs everywhere. Wherever we saw signs on our land, we would take them down. And then came the fight to claim what was ours. When the Funai report on our territory was due to be published, Ibama was against it. I asked myself, ‘why did they build a park in our territory?’”

Lucila Nawa (from behind) speaks to her relatives at a meeting with Funai in 2023: ‘Why did they build a park in our territory?’ Photo: Tarisson Nawa

Funai did not respond when SUMAÚMA asked about publication of the anthropological report and progress regarding demarcation. They did say that the delay in the Nawa process was due to various legal proceedings and lawsuits filed subsequent to publication of the anthropological study that had identified and delimited Nawa territory within the park.

This disagreement over Nawa territorial borders lasted until 2019, when an attempt was made to get Funai, ICMBio, the Acre State Environmental Department and the Nawa community itself to reach a consensus on borders. Nevertheless, under Bolsonaro, the process stalled once again.

During Tarisson’s time as a member of the Funai working group, he stressed the importance of the self-demarcation process that had begun in 2021. “The action of demarcating one’s own territory, putting up handwritten signs and reinforcing the ancestral struggle for life, as understood in the broadest possible sense, forced me to reflect deeply.” Tarisson considers self-demarcation “an Indigenous action to show the State that the lines it demarcates often don’t represent our notion of territory.”

Funai teams returned to Acre in 2023 to resume work identifying and delimiting Nawa territory; Tarisson was part of the group. Photos Tarisson Nawa

For Cacique Railson, demarcating Nawa territory is key to curbing invasions by loggers and drug trafficking across the territory. “We want to have a document for our land, a place just for indigenous people. If the land isn’t demarcated, non-Indigenous people will stay, and these non-Indigenous people are the biggest threats to living harmoniously in a territory,” he says.

For the Nawa, life can only go on if there is demarcation. “Without it, we can’t survive,” says the cacique.

Tarisson hopes his spirit will still be young when demarcation finally happens. And he will no longer have to watch his relatives die before their right to the territory is granted.

Inû Awá, a Nawa village inside the park, is sacred land; it is where Mariruni and other ancestors are buried. Photo Tarisson Nawa

In his dissertation on the Nawa, Tarisson wrote that the process of recovering Nawa memories had been a journey akin to going up a river utterly against the current. “And I didn’t go upstream with a motor or a paddle; I went upstream with a quant pole.” When he truly immersed himself in discovering his ancestry, the journey proved so difficult he had to punt, that is, to steady himself on a pole to propel the boat forward when things were most critical. The journey was tremendous, he told SUMAÚMA. “I jumped into a long and arduous movement, I was often tired, hurting, backbroken, sad and angry, but strengthened by seeing that, with each stroke, I became more aware of what I was and what I am,” he wrote in his thesis. The journey through turbulent waters continues, as Tarisson is all too aware. It will end only when the State finally recognizes that the land where his great-great-grandmother set down her roots is exactly where his people deserve to be.

Editing: Malu Delgado e Talita Bedinelli

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Spanish translation: Julieta Sueldo Boedo

English translation: Melissa Mann

Infographics: Rodolfo Almeida

Copyediting and finishing: Érica Saboya

Editorial workflow: Viviane Zandonadi

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum

Nawa youth still have hope that the territory will be officially delimited. The older members were not so blessed. Photo: Alexandre Cruz Noronha/Amazônia Real