The Legal Amazon’s six meatpacking plants authorized to export beef to the European Union have done little or nothing to adapt to the requirements in the EU Deforestation Regulation, issued by the economic bloc, which will take effect this year on December 30. A new Radar Verde study, shared with SUMAÚMA, shows that none of the exporters – Agra Agroindustrial de Alimentos, JBS, Marfrig Global Foods, Minerva, Naturafrig Alimentos, and Vale Grande Indústria e Comércio de Alimentos (Frialto) – implemented systems capable of controlling 100% of indirect suppliers, that is, the farms selling or transferring cattle from the Amazon region to other properties or intermediaries. Only Marfrig had already begun mapping its indirect chain, with 63% of the meatpacking plants at all of the companies included in the study controlling direct suppliers.

These companies, located in the state of Mato Grosso, have eight meatpacking plants and a total daily slaughter capacity of 5,870 animals. They have just been given extra time to, in practice, keep buying meat from deforested areas. That is because a group of 17 countries, including Brazil, have taken up exporter lobbying and asked to delay regulations that would stop the destruction of forests from being approved by European consumers.

Slaughter: no monitoring of meatpackers’ indirect supplier networks allows deforestation to grow. Photo: Marcello Casal Jr/Agência Brasil

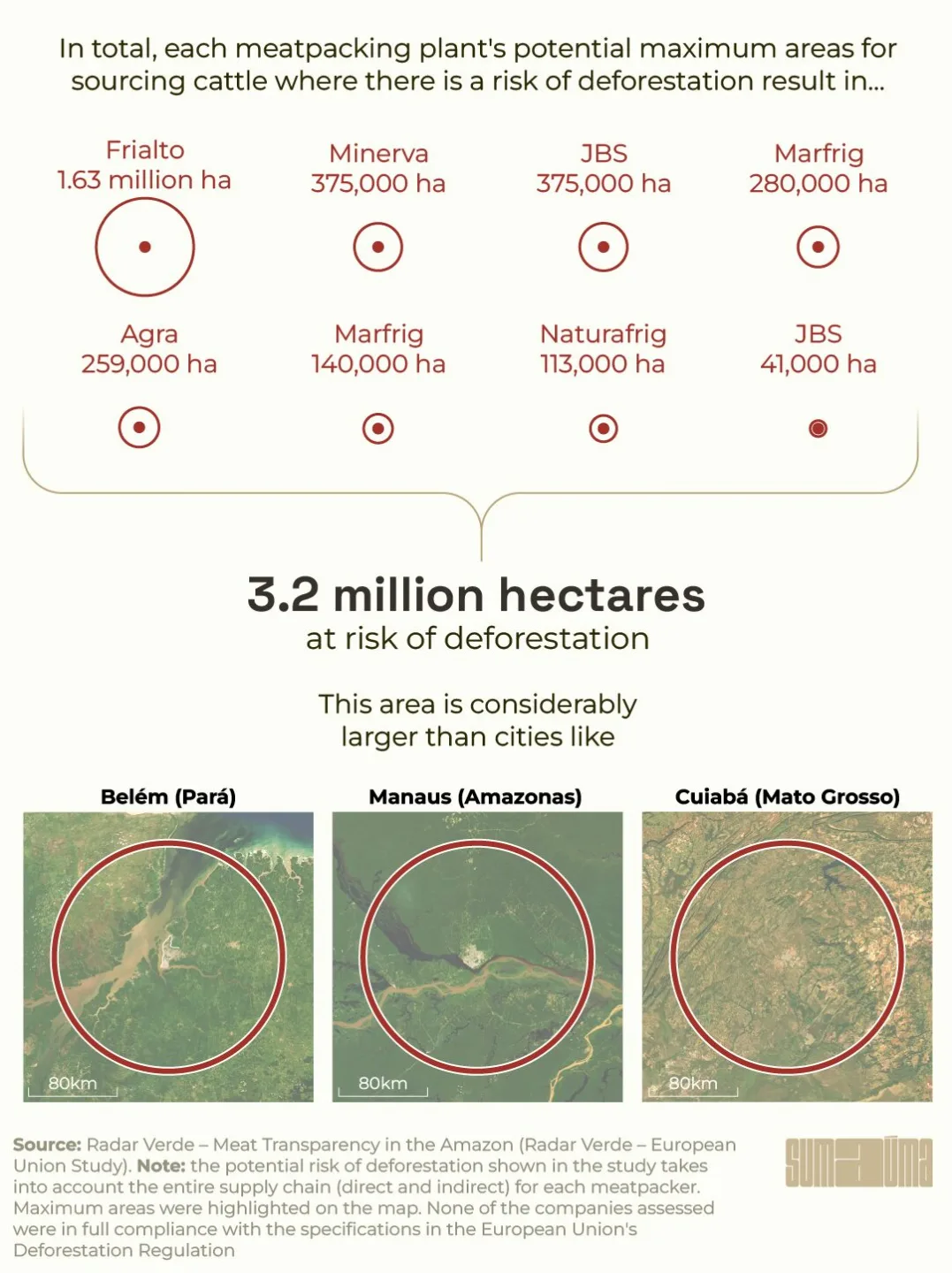

By extending the timeline to implement the European Union’s Deforestation Regulation, each exporter will be able to continue operating in a region where at least 100,000 hectares are exposed to the risk of deforestation. For an idea of what this number represents, imagine tens times the entire area of the city of Paris. Now multiply this area by each of the six meatpacking plants. This is the potential devastation to the forest that could still be jointly caused by these companies in their meat production chains if strict control measures are not taken. Radar Verde’s estimate is conservative and considers meatpacking plants’ area of operation.

On October 2, the European Commission introduced a proposal agreeing to hold off the Deforestation Regulation until 2026, bringing benefits to cocoa, coffee, palm oil, natural rubber, timber, and soybean exporters as well. Large producers, like the meatpacking plants, were given 12 additional months to adapt to the new standards, while small producers have at least 18 more months. Just one symbolic European Parliament vote is needed to approve this decision, which had already cleared the Council of the European Union on October 16. The European Parliament’s vote is set for November 14.

Radar Verde‘s unprecedented study on European Union exports looked at data collected in 2023. The project, which was supported by O Mundo que Queremos and the Amazon Institute of People and the Environment, gives consumers and financial sources insight into which meatpacking plants are in control of and transparent about their production chains, that is, whether or not they contribute to deforestation in the forest region.

“What we’re seeing is an ecosystem of leniency to guarantee that meat contaminated by deforestation continues to be exported,” says Paulo Barreto, an associate researcher at the Amazon Institute of People and the Environment. He says that this system involves everyone from the people deforesting to farms operating in illegal areas and, obviously, up through the meatpacking plants buying their products, financial backers who claim to be committed to solutions, and the government itself, which doesn’t always act with due transparency.

InfogrAPHIC: Rodolfo Almeida/SUMAÚMA

Researchers at Radar Verde arrived at the risk of deforestation indicator after doing an analysis using information provided by the companies’ own procurement areas on the sizes, in kilometers, of areas where meatpackers acquire cattle. Based on this data, a statistical model was built that considered every possible route – navigable rivers and official and unofficial roadways – to find the size of the cattle procurement zone. This number was used to calculate exposure to deforestation risk, considering variables such as environmental embargos in the procurement zone, any deforestation already inflicted on the region, and legal deforestation planned within the area.

Radar Verde asked all the exporters to provide evidence of their controls for their supplier chains over the last year. Although the European Union calls for transparency in reporting information on products sourced from areas at high risk for deforestation, none of the companies responded to the questionnaire.

SUMAÚMA reached out to all the meatpackers and asked for data on suppliers. Marfrig sent a statement sent by email saying that it already complies with the main aspects of the new European legislation, especially traceability. “The company monitors 100% of its direct suppliers in every region in Brazil. This year, it reached monitoring rates of 87% among indirect suppliers in the Amazon biome and 73% in the Cerrado, and the goal is to reach 100% traceability by 2025. These are the industry’s highest indirect [supplier] control rates in Brazil.” According to Marfrig, all indirect suppliers located in high-risk areas are already 100% monitored by the Social and Environmental Risk Mitigation Map, a company tool that cross-references data on livestock distribution in biomes with areas at risk for deforestation, old growth native vegetation, regions of social conflict, and Indigenous and Quilombola territories.

JBS also said by email that it has applied geospatial monitoring to potential suppliers since 2009. “The JBS Raw Material Procurement Policy blocks purchases from properties with illegal deforestation, areas under environmental embargo, conservation units, and Indigenous or Quilombola territories, among other requirements such as inclusion on the Forced Labor Blacklist,” said the company. In 2021, JBS created the Transparent Livestock Platform, allowing direct suppliers to apply the same social and environmental criteria the company demands to their own animal suppliers. According to the company, as of January 1, 2026, only producers on the Platform will be allowed to sell cattle to JBS.

The other companies mentioned in Radar Verde’s European Union study did not respond to SUMAÚMA’s contacts.

InfogrAPHIC: Rodolfo Almeida/SUMAÚMA

Signals crossed within the government

The Environment and Climate Change Ministry reasserted its control over livestock farming after Marina Silva was reappointed to lead it in 2023, with the goal of fighting the climate emergency caused by atmospheric gas emissions from this activity. Nevertheless, the Agriculture Ministry, a key player in this discussion, argues the European regulation will have little or no impact on fighting deforestation, since it will require agricultural products to be sourced from areas that were deforestation-free since 2020, something which, according to the ministry’s current managers, mostly already occurs now. As indicated by the Radar Verde study, agriculture is responsible for 27% of Brazil’s greenhouse gas emissions – with 22% coming from livestock farming alone, according to the System of Estimates on Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Removals.

Pressure from the Brazilian government to defer the Deforestation Regulation included direct action by Vice President Geraldo Alckmin, a member of the Brazilian Socialist Party as well as the minister of Development, Industry, Commerce and Services and the head of the Agriculture and Foreign Relations ministries. Alckmin said Brazil is an “example of renewable energy and the fight against illegal deforestation” and that this postponement was necessary for the Brazilian government to show the European authorities this.

Responding to SUMAÚMA, the ministry led by Alckmin guaranteed that “the Brazilian government is unequivocally committed to fighting deforestation” – August 2023 to July 2024 saw the largest proportional decrease on record for deforestation in the Amazon, of 45.7%. The government says the goal of eliminating deforestation in the biome by 2030 remains. “What the Brazilian government and other countries are asking for is more clarity in relation to the criteria, metrics, systems of verification, and other points in the European legislation, and for these criteria to be based on science, so the measure does indeed attain its stated objectives and does not become a unilateral mechanism of green protectionism camouflaged in good environmental intentions,” reads the statement.

The Agriculture Ministry told SUMAÚMA its position has been very clear since the initial phase of discussions on the legislation in Brussels. The Deforestation Regulation, reads a message from the ministry’s press office, “is a unilateral and punitive instrument that fails to consider national laws to fight deforestation.” As the ministry sees it, the rule imposed by the European Union “has extra-territorial aspects that violate the principle of sovereignty, establishing discriminatory treatment by disproportionately affecting countries with forest resources, increasing the cost of the production and export process, especially for small producers, and violating principles and rules of the multilateral trade system, as well as commitments signed in multilateral environmental agreements.”

The European Deforestation Regulation really does fail to consider the particularities of Brazil’s Forest Code, a set of laws regulating the use and protection of forests and aimed at reconciling economic development, especially in the agricultural sector, with environmental conservation. The first version of the code was enacted in 1934, yet it has undergone a variety of changes, the most significant of which was a reform in 2012. This national regulation permits legal deforestation, or rather, it allows authorized removal of native vegetation within legally established limits, which are 20% within the Legal Amazon’s forest area and 65% in the Cerrado. And this is the point of contention between Brazil and the European Union. The European measure stipulates that products sold to the continent must come from deforestation-free areas, with no regard as to whether deforestation is or is not legal.

Sides: Agriculture Minister Carlos Fávaro (left) and Vice President Alckmin are working to delay the regulation; Marina wants more control over livestock. Photos: Ton Molina and Pedro Ladeira/Folhapress

Paulo Barreto, a researcher at the Amazon Institute of People and the Environment, explains that the European Union does not have confidence in Brazil’s rules because it is normal to change laws in the country so they fit specific economic interests. “The Forest Code passed in 2012 forgave 40 million hectares of illegal deforestation. What’s more, Congress frequently seeks to pass land regularization laws, which in practice means legalizing land-grabbing,” he says.

This well-known tradition in Brazilian politics, of legalizing illegal practices to continually occupy public lands, feeds not only the Amazon’s deforestation, but is also directly connected to violence and successive violations of Indigenous, Ribeirinho, and Quilombola rights. “Land-grabbing is not only a lucrative activity, it ends up making its practitioners more politically influential. The people stealing public lands have a lot of money and end up gaining political power, whether by funding electoral campaigns or by becoming politicians themselves,” Barreto points out.

Taking a different tack, the Agriculture Ministry emphasizes that Brazilian production is the most sustainable in the world and it is the country best suited to complying with European Union requirements, as long as the rules are established in advance and timelines are adapted for compliance. “No industry or exporter country is completely adapted [to the Deforestation Regulation], since the EU did not make the evidentiary criteria clear. The EU (…) recognized that exporter countries do not have the conditions to meet the requirements, especially developing countries and small farmers,” the ministry’s press office said in a statement sent to SUMAÚMA.

Dispute: the federal government is planning complex operations to remove cattle from illegal areas, such as in the Jamanxim National Forest, in Pará. Photo: Avener Prado/SUMAÚMA

Why put off confronting the climate crisis?

SUMAÚMA asked for an interview with Agriculture Minister Carlos Fávaro, to understand the reasoning for holding off a regulation that could help to combat the climate emergency precisely at a time when the problems caused by this same crisis are affecting agricultural production in other regions, especially the production of food for domestic consumption. The state of Rio Grande do Sul is a recent example. According to the National Confederation of Municipalities, the heavy rains that ravaged the state in 2024 caused R$ 4.9 billion (US$ 850 million) in damages to the state’s agriculture operations and R$ 514.8 million (US$ 89,3 million) to the livestock industry.

The Agriculture Ministry provided a perfunctory statement: “Brazil is willing to explore, bilaterally and in the appropriate regional and international forums, ways to intensify Brazil-EU cooperation to preserve the forests.” The ministry used the text to explain that its goal “is really effective protection that considers the reality in Brazil, promotes the three dimensions of sustainable development, and respects our environmental laws, some of the most advanced in the world.”

The ministry sees large exporters as having the resources to adapt their production chains to comply with European Union requirements. Consequently, the ministry notes, “they will charge more for this.” Brazil’s central concern, the ministry says, is “small producers, who will face greater hardships to comply with these requirements.”

Brazil, along with Sweden, Portugal and Slovakia, has been making the argument that small producers are more vulnerable to the implementation of the EU Deforestation Regulation and they need special support, and that the term environmental degradation must be better defined. Barreto, however, contests this claim, estimating that just 25% of Brazil’s herds are on small farms. He says mechanisms can be developed to include these producers in the sourcing controls required by the EU, as was done in the past with hoof-and-mouth disease vaccinations.

“In the 1990s, we vaccinated around 10% of the herd; today, we vaccinate practically every animal, even those with small producers, since the cost of this control system is already built in. This added billions of dollars to exports. Right now, Brazil sends around 25% of everything it produces abroad; but in the 1990s, this figure was under 5%,” the researcher says.

The European Union’s Deforestation Regulation, accused by the federal government of violating national sovereignty, considers several variables related to crises in the field. The economic bloc will require exporters to consult and cooperate in good faith with Indigenous peoples, and to assess whether these original communities have made any claims that their properties have been invaded to produce agricultural products sold in a natural state, in other words, with very little industrialization.

Other variables that should influence exporters in creating an indicator of risk are level of corruption, prevalence of document and data falsification, lack of law enforcement, violations of international human rights, armed conflict or sanctions imposed by the United Nations Security Council or the Council of the European Union.

What is at stake and consumer power

The European market is the third largest buyer of Brazilian meat, trailing China and the USA. In 2023, Brazil exported 77,600 metric tons to the European Union, generating US$ 554.4 million in revenue. The Radar Verde study suggests that Brazil needs to connect the origin control used for health purposes, managed under the Agriculture Ministry’s Brazilian System of Individual Identification of Cattle and Buffaloes, to social and environmental control to thus trace both direct and indirect suppliers.

Pressure from international and domestic customers is seen as fundamental to promoting changes. In Europe, civil society organizations sent a letter to the European Union’s member States arguing against the postponement of the Deforestation Regulation. “One of the [EU Deforestation Regulation’s] innovations is that it tackles unsustainable agricultural expansion, which the journal Science estimates to be behind 90-99% of tropical deforestation,” the document says. What consumers and civil society are alleging is that the European Union’s agriculture ministers made last-minute efforts to hold off the regulation, ignoring not just the urgency of the climate and biodiversity crises, but also sectors that already operate with traceability and in compliance with these rules, such as the cocoa and rubber industries.

Radar Verde also shows that European meat retailers and financial institutions operating in Brazil could benefit from tougher rules against deforestation.

A study by the Brazilian Institute of Consumer Defense, published in a report on responsible banks in 2020, revealed that financial institutions in the Netherlands, Germany, and Norway invested over US$ 11 billion in 26 large Brazilian retail and agribusiness companies that were at high risk for involvement with deforestation in the Cerrado and the Amazon. These include the Casino group, which owns the Pão de Açúcar chain of supermarkets and is accused in a suit brought by Indigenous peoples in Brazil and Colombia of selling meat connected to land-grabbing and deforestation in the Amazon.

Conscience: large companies like the Casino group, which owns a chain of supermarkets, were cited as selling meat connected to land-grabbing in a suit brought by Indigenous people. Photo: Lela Beltrão/SUMAÚMA

In Brazil, the meatpackers signed a Conduct Modification Agreement with the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office in 2009, promising not to purchase cattle from farms that violate the law, whether by illegally deforesting land, invading Indigenous territories, or using forced labor. Despite this advancement, the measure was insufficient to prevent deforestation, which under the far-right Jair Bolsonaro administration reached an average of 11,300 square kilometers of area felled per year, equal to the area of the Free Trade Zone of Manaus, which includes the state capital of Amazonas and the municipalities of Presidente Figueiredo and Rio Preto da Eva.

Pressure from customers has also caused the financial sector to move to restrict credit to those perpetrating deforestation. In 2021, the Central Bank of Brazil, through Resolution 140/2021, reinforced social and environmental criteria for granting rural credit, such as requiring that property be listed in the Environmental Registry of Rural Properties and blocking credit for properties in protected areas or areas with a history of illegal deforestation in the Amazon. Two years later, this rule was extended to all of the biomes.

In 2023, the Brazilian Federation of Banks launched a rule requiring meatpackers to implement systems to trace and monitor suppliers, guaranteeing that by December 2025 they would not source cattle from areas involved with illegal deforestation in the Legal Amazon. The measure is in addition to prior initiatives, such as the “Cattle on Track” Protocol, created by the Institute for Forestry and Agricultural Management and Certification in partnership with the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office, in an effort to speed up implementation of the commitments undertaken by the cattle chain in the Amazon under the Conduct Modification Agreement.

These measures are, however, self-regulating, which means that at the end of the day the banks are deciding on possible punishments for clients operating in deforested areas. Restricting credit is one possible punishment.

A National Monetary Council resolution dated June 2023 also set rules for granting rural credit in Brazil, stipulating that social, environmental, and climate obstacles be considered. “Yet many of these criteria, such as registration with the Environmental Registry of Rural Properties and having land that does not encroach on Conservation Units or Indigenous Territories, have already been discussed and defined by the meat industry’s Conduct Modification Agreement through the Cattle on Track Protocol since 2019,” says Camila Trigueiro, a researcher with Radar Verde. Nevertheless, none of it was enough to stop the destruction of life and forests.

Unfortunately, as made clear by this year’s droughts and fires, the Amazon is out of time to wait for goodwill.

Future: agriculture accounts for 27% of Brazil’s greenhouse gas emissions; the life of the planet demands a swift change of course. Photo: Lela Beltrão/SUMAÚMA

Report and text: Regiane Oliveira

Editing: Malu Delgado

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Fact-checker: Gustavo Queiroz and Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

English translation: Sarah J. Johnson

Spanish translation: Julieta Sueldo Boedo

Editorial workflow coordination: Viviane Zandonadi

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum