I thought I’d gotten lucky. It was late on a sweltering morning in Belém when I arrived at the Amazon Summit, dripping with sweat after a march by civil society organizations. At the door of the Hangar convention center, I ran into cacique [indigenous leader] Raoni. In January of this year, during the presidential inauguration, I had been moved to tears watching the iconic Indigenous leader walk up the ramp of the presidential palace alongside Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. But eight months later, what looked like a possible opportunity to interview Raoni turned into a surreal day, when I became an unwitting witness to the Brazilian president brushing off the 90-year-old Kayapó leader. Stranger still, I ended up buying the latter lunch.

For three years, I had tried to get an interview with Raoni, but his aides kept giving me the runaround and I’d all but given up. When I bumped into him and four other Indigenous men at the summit, I decided to ask him personally. Patxon Metuktire, Raoni’s grandson and interpreter, turned down my request but invited me to accompany the group. Raoni wanted to enter the Hangar so he could speak to the plenary session, but he didn’t have any authorization. Patxon figured my press pass might be useful if security barred the elderly leader at the door of the convention center in Belém, where Lula was receiving the leaders of Amazon countries on August 8. Hoping someone might throw me a bone, I agreed.

Security recognized Raoni right away at the side checkpoint, where the press and delegations from Amazon countries entered the building. They sent us over to a second checkpoint, near the Hangar garage, where delegations went into the plenary session. The elderly leader shuffled his way up the much humbler ramp leading to the entrance and stood there. Caught off guard by the surprise visitor, security radioed the event organizers. Meanwhile, the guards fawned over Raoni, offering him water, asking if he needed to use the restroom, getting him a chair. One of the staff wanted a selfie. “My great-grandfather was an Indian!” he proclaimed.

A few minutes later, Wagner Caetano de Oliveira, Secretary of Political and Social Relations with the Secretary-General of the Presidency, came down to greet the Kayapó elder. Caetano was in the company of Lula’s press secretary, José Chrispiniano, who glared at me—the last thing he needed at a potentially awkward moment was a reporter around. No point protesting that I was only there by chance. From that moment on, I was seen as “embedded” with the Kayapó delegation.

Caetano told Raoni how things would go: he would be taken to meet Lula and other heads of state—without the press—and the two of them would talk for five minutes. The cacique immediately rose from his chair and chewed out the secretary: he didn’t just want to be received; he wanted to address the plenary session, as he had done three days earlier at the opening of the Amazon Dialogues, the gathering attended by organizations from civil society. Caetano said he’d see what he could do.

Lula was annoyed by the request. The summit had gotten off to a late start, the president didn’t know what Raoni planned to say to attendees, and he was also worried the cacique might embarrass him in front of the other presidents. So at first Lula said he wouldn’t receive the Kayapó leader. Thus began a four-hour-long operation to string Raoni along.

Around noon, Caetano came back down to talk to us (by that point, it really was “us”). He said everything was behind schedule and suggested we go for lunch while the leaders were making their opening remarks. We were advised to be back by 1 o’clock sharp, because Lula would receive Raoni before he himself went to lunch. “And then, since you two are friends, you can ask to address the plenary session.” But eat where? I suggested we take Raoni to the press room, where lunch was served every day (never in the history of Brazil have reporters been treated so well). “Noooooo, too much hassle,” was the reply. I didn’t push it. They proposed we call an Uber, but Patxon was adamant that the summit should provide a van. OK, you win, van it is. “Reporter, you come with us,” Raoni declared. Lunch with Raoni? Who was I to say no?

We climbed into the official van in a race against time. We would have to exit the center, confront heavy traffic, grab lunch, and be back by 1:00 pm max. The only person familiar with the city was the driver, who, oblivious to our time constraints, suggested Mangal das Garças, a park half an hour’s drive from the Hangar.

Excited by their apparent victory so far, the Kayapó had another problem to deal with: who was going to pay for lunch? The question, asked in Portuguese, triggered a volley of comments in Kayapó. I caught only one word—“journalist”—which made it clear why Patxon had insisted I go with them.

After we’d spent 15 minutes in traffic, I put the kibosh on Mangal das Garças and asked the driver to please just find a place where we could catch a bite in 15 minutes and hurry back. It was already past noon. The fellow said he knew where we could get a superb blue-plate special. “Anything at this point,” I said. And that’s how the great Raoni Metuktire, received around the world by kings and presidents, ended up having lunch at a greasy spoon in Belém, the kind of place that serves filtered water in repurposed soda bottles. As I had rightfully guessed, the bill for all six of us was mine.

On the ride back, I asked Raoni why he wanted to talk to Lula so badly. “I want to tell him we should work together for the Amazon,” he replied. Had the president known, he wouldn’t have felt the need to string the cacique along.

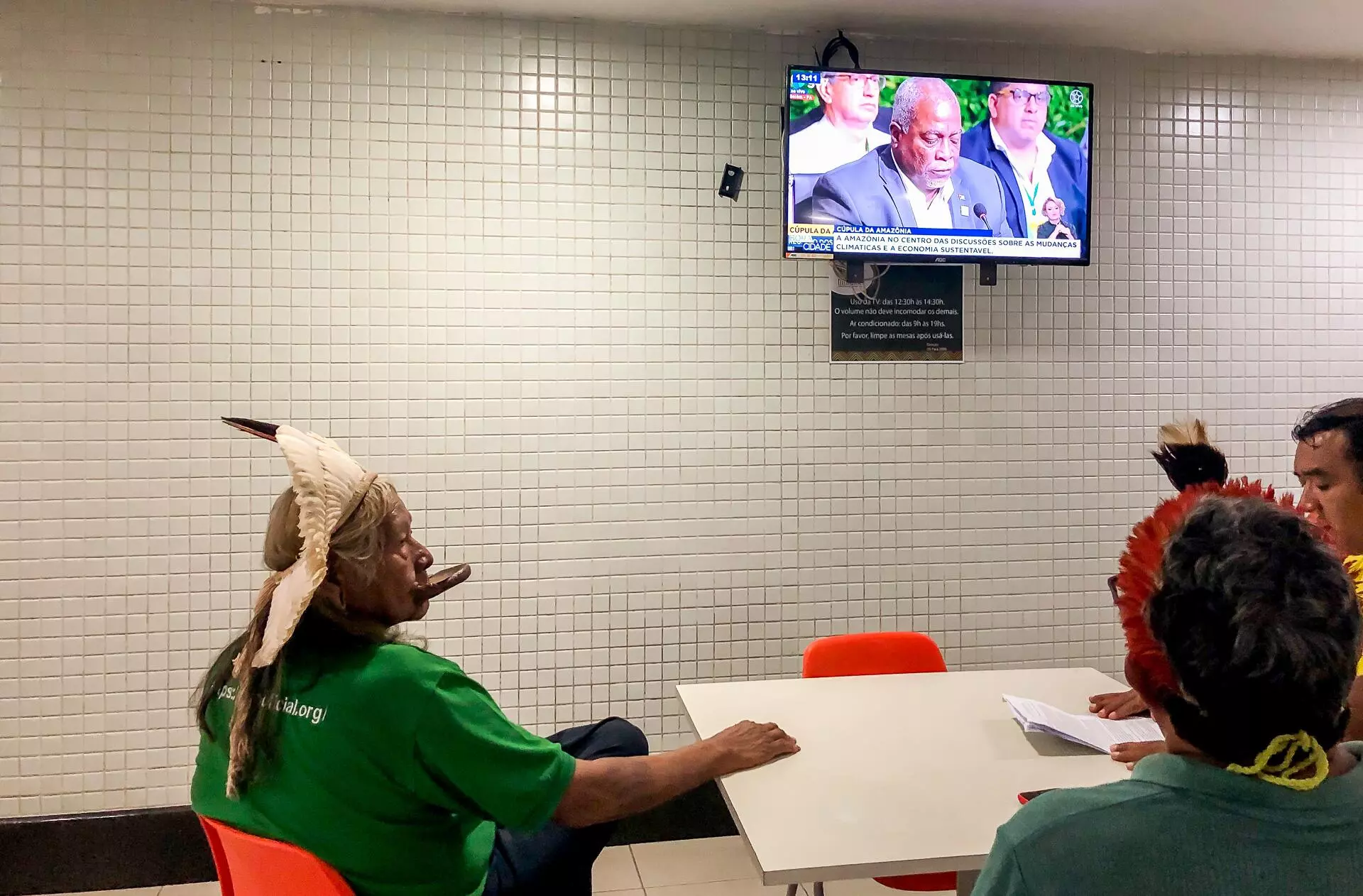

We reached the Hangar at 1:05 pm—quite punctual by Brazilian standards. Patxon sent word to the Secretary-General. It was an unbearably hot afternoon, and security sent us to an air-conditioned spot at the back of the Hangar, where security staff ate their lunch. They made Raoni comfortable there, providing him with water, coffee, and a television set where he could watch coverage of the event he wanted to attend. After a while, Caetano appeared to inform the group of Kayapós that Lula had unfortunately gone to lunch with the Amazon leaders. The cacique would have to wait to see him.

As directed by the Secretary-General of the Presidency, Raoni waited for Lula in a lunchroom at the convention center where the Amazon Summit was held. Photo: Claudio Angelo

We waited more than three hours in the lunchroom. I took advantage of this privileged opportunity to do the interview I’d coveted for three years. A Colombian journalist who had gotten lost in the convention center and found himself at the delegation entrance slipped into the lunchroom and got an exclusive (luck was with someone that day). Frustrated, Raoni got up several times, went out, smoked his pipe, and came back. Patxon started threatening to leave, because Raoni had a plane to catch at 5:40 pm. And still no end to Lula’s lunch.

It was after 3:30 pm and the Kayapó entourage was already preparing to leave when we got the word: a group of Brazilian cabinet ministers was coming down to meet with the cacique. The Secretary-General of the Presidency, Márcio Macêdo, entered the lunch room accompanied by Indigenous Peoples Minister Sônia Guajajara; Health Minister Nísia Trindade (who seemed as thrilled as I was to meet the cacique); Environment and Climate Change Minister Marina Silva; and Marina’s executive secretary, João Paulo Capobianco. At no point was the Indigenous leader invited to go upstairs to meet the regional presidents, even if only in an antechamber. There in a backroom cafeteria, surrounded by tiled walls, thermos bottles of coffee, and microwave ovens, members of the top echelon of the Brazilian government received the country’s greatest Indigenous leader.

After waiting more than three hours, the Presidency sent cabinet ministers to talk to Raoni. Lula didn’t show. Photo: Solange Barreira/Observatório do Clima

By way of apology, Macêdo explained that Lula was having bilateral talks with other presidents and wouldn’t be able to speak to the Kayapó leader after all. Raoni reacted good-naturedly: “The next time we meet, I’m going to give him a good scolding.” He said the matters at hand were of vital importance and the ministers should take a firm stance to eliminate illegal mining on Indigenous lands and halt deforestation. He also used the occasion to address a few local demands: the opening of a road to facilitate shipment of tonka beans gathered by a certain village; more health care inside of the Kayapó territory; and the appointment of a member of the Kayapó people to Brazil’s federal agency of Indigenous affairs, Funai (Macêdo mistook the latter document for a letter to Lula and promised he would deliver it to the president).

In refusing to break protocol, Lula not only failed to show respect for an elderly Indigenous leader and offended the ally whose picture appears on the cover of the Presidency’s Flickr account. He also fumbled the chance to feature a powerful image at the Amazon Summit: a symbol of the Amazon itself addressing regional heads of state and showing that the nods to Indigenous peoples included in the summit’s final declaration by members of the Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization (ACTO) aren’t merely ink on paper. Colombian President Gustavo Petro gave the only speech that day aligned with the needs of a biome close to the point of collapse and a planet grappling with a climate emergency. Alone in speaking truth to his colleagues, Petro certainly would have appreciated Raoni’s presence at the event.

*Claudio Angelo is coordinator of Communication and Climate Policy for the Climate Observatory and a contributor to SUMAÚMA

Fact check: Douglas Maia

Spell check (Portuguese): Elvira Gago

Translation into Spanish: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Diane Whitty

Photography editing: Lela Beltrão

Page setup: Érica Saboya