Seven years after being forced from the banks and islands of the Xingu River by the construction of the Belo Monte hydroelectric plant, around 300 ribeirinho (people from traditional forest communities whose lives are closely linked to the rivers of the Amazon) families in the Altamira region, in the state of Pará, are still waiting for promised land with which they hope to recover their way of life. The creation of the so-called Ribeirinho Territory, approved in 2019 by Ibama, Brazil’s environment agency, as a way of repairing the lives of this traditional community, is one of the conditions the agency has set for the renewal of Belo Monte’s operating license, the application for which it is currently examining. The creation of the Ribeirinho Territory will require the appropriation of land by Norte Energia, the holder of the concession to operate the hydroelectric plant. But its lack of action as well as Ibama’s inability to enforce the requirement, has fueled a new offensive against the project by Brazil’s agricultural sector. both in the region and through allies in Brasilia.

Ibama’s first technical report on the requirements for renewing the license, issued in June 2022, described Norte Energia’s position on the Ribeirinho Territory as “ambiguous.” At the time, the company contacted families who would potentially benefit from the creation of the territory to confirm their interest in resettlement, even though its implementation had yet to begin. Ibama went on to say that Norte Energia’s position “requires disproportionate and unusual resilience from the families affected.”

Aerial view of the Belo Monte hydroelectric plant in Altamira. Photo: Pablo Albarenga

Norte Energia’s Director of Institutional Relations, Eduardo Camillo, did little to dispel such ambiguity when he received a delegation led by Brazilian senators Zequinha Marinho, of the Liberal Party, and Damares Alves, of the Republicans, at Altamira airport towards the end of March. The two politicians, allies of Jair Bolsonaro, had called an open meeting in the city to discuss ways to prevent the creation of the Ribeirinho Territory, which included trying to form an external commission on the topic in the Senate, which would comprise Hamilton Mourão (Republicans), a retired general and vice-president in Bolsonaro’s far-right government, and Tereza Cristina, of the Progressistas Party, Bolsonaro’s Minister of Agriculture.

In many respects the meeting, which took place on March 23, mirrored another held earlier that month, also in Altamira, convened by Norte Energia itself at the request of Siralta, the city’s Rural Producers Union. On that occasion, Siralta had suggested a drastic reduction in the size of the Ribeirinho Territory, restricting it to the Permanent Preservation Area of the plant’s reservoir – a strip of varying dimensions, but whose width never exceeds 500 meters at the water’s edge, and for which landowners had already been compensated during the Belo Monte licensing process. Under this proposal, in exchange for giving up land for subsistence farming and the raising of animals such as chickens, which would involve the expropriation of 8,400 hectares, the ribeirinho families would be paid for performing environmental services – in other words, for conserving or recovering the Permanent Preservation Area, something that had never been considered under the plan that aims to rebuild their way of life.

In response to Siralta’s proposal, Ibama analyst Henrique Marques Ribeiro da Silva – who participated in the meeting by video – said the questions raised by the rural workers’ union were out of date, having been superseded by the approval, four years previously, of the current plan for the Ribeirinho Territory. He once again accused Norte Energia of delaying the implementation of the territory – the company has not yet purchased any of the areas needed to resettle ribeirinho dwellers, although some landowners have expressed their willingness to sell.

Although Ibama considers the case presented by Siralta closed, Eduardo Camillo not only received Marinho and Alves, but also attended the March 23 meeting, which lasted for three hours and which was attended by 200 people at Altamira’s Center for Conventions and Courses. He also failed to comment when Marinho promised the ruralists that their first step would be to mount a legal campaign to prevent the land necessary for the creation of the Ribeirinho Territory being subject to a Declaration of Public Utility by Brazil’s National Electric Energy Agency, Aneel. Public utility status would accelerate the expropriations, and Aneel has already published a favorable legal report on the matter in May last year. The final decision, however, has not yet been confirmed, as Norte Energia, which filed the DPU request in October 2021, has been slow to provide the necessary information, and even made errors in filling out the request, as can be seen from Ibama files viewed by SUMAÚMA.

Norte Energia refused to answer any of SUMAÚMA’s questions about the Ribeirinho Territory, including regarding the reason for Eduardo Camillo’s presence at the meeting led by Zequinha Marinho and Damares Alves. Instead, the company would only state that “all questions regarding the Ribeirinho Territory are being directly addressed with Ibama and other competent agencies.” The fact is, however, the company’s delay paves the way for ruralists in Altamira to bring pressure against the successful completion of a reparation process in which the traditional communities of the Xingu River have taken control of their destiny, in a campaign born of the destruction caused by Belo Monte.

Ribeirinha resistance

Maria Francineide Ferreira dos Santos has followed the struggle since the beginning. A 53-year-old “born ribeirinha” from Paratizinho, one of the islands of the Xingu affected by changes to the course of the river, she is temporarily living on Pedacinho do Céu island until, as she puts it, her “territory is ready.” “We have the right to have our way of life respected, because we existed before Belo Monte. Our strength doesn’t just come from us, it comes from our rights, it comes from the freedom to have what we’ve always, but no longer, have,” said Francineide, in an interview at the headquarters of Movimento Xingu Vivo (the Xingu Lives Movement) in Altamira.

Her family, and those of the other ribeirinhos in the region, lost everything they needed to live, but were not even considered in the Belo Monte licensing process until 2015. That was when, shortly before the plant’s operating license was issued, large numbers of them contacted the Attorney General’s Office in Altamira, saying the compensation they had received from Norte Energia barely made up for the upheaval to their way of life, yet was supposed to compensate for their expulsion from the beiradões (riverside beaches) they occupied – or else they had been asked to choose between resettlement in rural areas far from the Xingu, or in Collective Urban Resettlements, drab housing developments built by the company on the outskirts of Altamira.

Maria Francineide Ferreira dos Santos, aged 53 and born and raised on Paratizinho, one of the islands of the Xingu: she and her family have lost everything and wait in Altamira for a new territory in which to live. Photo: Soll Souza / Sumaúma

In light of the complaints, investigations on the islands and banks of the Xingu River ordered by federal prosecutor Thais Santi – responsible for ensuring the rights of traditional and indigenous communities and the environment in Altamira – led to the “discovery”, hitherto ignored by Norte Energia, that traditional ribeirinho dwellers often have two houses: one on the riverbank and the other as a support base in the city. Many had already been victims of violence prior to the expulsions caused by the plant, when the creation and expansion of farms, in a region where land grabbing prevails and where few have definitive titles to their lands, pushed them to the banks and islands of the Xingu.

Faced with the challenge of understanding the needs of this underserved population, Santi asked for help from the Brazilian Society for the Progress of Science, which tasked its most renowned specialists with listening to the ribeirinho people and studying their way of life. The project, coordinated by anthropologists Manuela Carneiro da Cunha, a retired professor at the University of São Paulo, and Sônia Magalhães, from the Federal University of Pará, resulted in a report, which later became a book entitled The Expulsion of the Ribeirinhos of Belo Monte.

At the 2016 public audience in Altamira where they revealed their findings, the anthropologists did not suggest a plan for the Ribeirinho Territory or define who would live there. They said it was the members of the traditional community in the area of influence of Belo Monte who should recognize their fellow ribeirinhos and present a plan to rebuild their way of life. This resulted in the creation of the Ribeirinho Council, which led the so-called “process of social recognition.”

From this, the criteria that define the traditional riverside community were established: a history of living on the river; strong neighborly relationships, involving experiences of sharing and caring for fields and houses in case a family is temporarily absent; a mixture of fishing activities, subsistence farming, animal breeding, hunting and extractivism; and the existence of two dwellings, one where people live and the other, “on the street”, used as a support point for access to health, education and the sale of products such as fish or flour. Based on these criteria, the Ribeirinho Council identified the families that should have their rights restored, and the plan for the Ribeirinho Territory was proposed, comprising three different areas on both banks of the Xingu, on the outskirts of Altamira.

A traditional community under attack

At the meeting attended by Damares Alves and Zequinha Marinho, both the ribeirinho way of life and this process of mobilizing the community came under attack. Senator Alves said “a ribeirinho is someone who lives on the riverside”, equating the owners of large farms along the Xingu with members of traditional communities. Jorge Gonçalves, a Siralta director who owns a property subject to partial expropriation to allow the creation of the Ribeirinho Territory, said he believes that both ribeirinhos and large agricultural producers are “riverside people.” “Some developed their financial and social conditions a little more, raised their children, introduced them to other worlds, but their origins are the same,” he argued. Afterwards, he attacked the academics of the Brazilian Society for the Progress of Science: “We let someone in from outside, with their little dossiers, commanded and paid for by someone, so that they can change our way of life.”

The Ribeirinho Council was not invited to the meeting, but, alongside the rural landowners, there were ribeirinhos who had abandoned the idea of living in the Ribeirinho Territory, fishermen, potters and those from other communities whose demands had yet to be met by Norte Energia. The focus of the interventions, however, were the landowners and land grabbers threatened with expulsion by the implementation of the Ribeirinho Territory.

An aerial view of the Collective Urban Resettlements in Altamira, where ‘ribeirinho’ families were relocated after losing their connection to the Xingu River and experiencing enormous upheaval in their lives following the construction of Belo Monte. Photo: Pablo Albarenga

A Siralta-produced video – in which only small landowners on the eviction list spoke – was screened at the event. Some of those who appeared in it said they would leave for “a fair price”, while others didn’t want to leave because of their attachment to the land, like Ronaldo Rodrigues Vaz from the midwestern state of Goiás, who has been in Altamira for 43 years and claimed to own only 43 hectares, on which he lives with his eldest son. Siralta’s lawyer Alfredo Bertunes also spoke at the meeting, claiming the “vast majority” of the 94 properties to be totally or partially expropriated were small. “The plan is creating antagonism in rural areas. It is not the only way to comply with the requirement (for the renewal of the license). There are other ways that would have less impact on the lives of these rural producers,” he said, raising the specter of the violence that has marked the growth of Altamira, a center of constant agrarian and environmental conflicts.

However, the video and Bertunes’ account are misleading, as the list of potential expropriations also includes a number of large farms, according to a document attached to the DPU request Norte Energia has filed with Aneel. The same document reveals that some individuals own several properties classified as small – or less than four rural modules in size, according to the criteria of Brazil’s National Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform. In Altamira, each rural module has 75 hectares. One landowner, Ilma de Melo, has six small properties, while another, Elisvaldo Menezes de Oliveira, is registered as the owner of five. When these properties are added together, such landowners can no longer be considered smallholders. Well-known large-scale landowners on the list include the former mayor of Altamira Wanderlan de Oliveira Cruz, who has three properties in the area proposed for the Ribeirinho Territory, totaling 287 hectares, of which 218 hectares would be expropriated, and the Lorenzoni family, which owns two farms with a total area of 581.5 hectares, of which 389.2 hectares will potentially be expropriated. Another former Altamira mayor, Odileida Maria de Souza Sampaio, owns a 405.7 hectare property, of which 232.6 hectares would be expropriated, while there are also two companies on the list – HD Empreendimentos (the owner of 4,130.9 hectares, of which 934 hectares would be expropriated), and Ecopalma Agroindústria Palmiteira (the owner of two farms totalling 868 hectares, of which 101 hectares would be expropriated).

Bolsonarists take aim at public prosecutor

A frequent complaint from landowners is the price offered by Norte Energia, which, they say, is based on unadjusted 2013 land values, in a region where Belo Monte has made everything more expensive. Siralta president Maria Augusta Silva Neta told SUMAÚMA the union had contracted a surveyors report and presented Norte Energia with “a real price list.” “There are some people who say ‘I’m too old to go somewhere else’, but there are others who are keen to move, the topography in the river areas is no good for machinery. [But] the price list is terrible, and if they create the DPU, forget it,” she said. Even while demanding a better price for the land to be expropriated, Maria Augusta attempted to distance the company from the Declaration of Public Utility request made to Aneel. “Norte Energia has to comply with the recommendations and determinations that have been imposed. The cause of all these problems is who’s doing the imposing. It’s Ibama, pressured by the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office,” she said.

Maria Augusta Neta, president of Siralta, the Altamira Rural Workers Union, in an interview with Sumaúma in which she criticized the position of Ibama and the Public Prosecutor’s Office. Photo: Rodrigo Correia / Sumaúma

The artillery arrayed against Brazil’s Public Prosecutor’s office, which has yet to request a single court order in relation to the Ribeirinho Territory, was demonstrated by the words of Zequinha Marinho, and also by Hamilton Mourão, who recorded a video message played at the March 23 meeting. The Ribeirinho Territory is a work of fiction imposed by the Public Prosecutor’s Office and carried out by Ibama,” claimed the retired general. Questioned by SUMAÚMA, prosecutor Thais Santi, who has been working in Altamira for ten years, said the forced expulsions the Belo Monte hydroelectric plant imposed on those living along the Xingu River was one of the most serious human rights violations in the entire history of the plant. The process, she argues, was made possible by the invisibility of a traditional population that had, throughout its history, established a unique way of life, linked to the dynamics of the river and the city. “The role of the Federal Prosecutor’s Office in this case is centered around efforts to avoid further human rights violations, the silencing of and disrespect for the ribeirinho way of life, by demanding this traditional population from the Xingu River has an active role in the process,” she said.

The Ribeirinho Council is not standing still. A number of its 14 members were in Brasília this year, for talks with Ibama and Brazil’s ministries of Environment and Climate Change, Agrarian Development and Human Rights and Citizenship. According to the council, Ibama told its representatives the meetings of the project’s opponents would not change anything, as the territory has already been approved, is one of the requirements for the renewal of the Belo Monte license, and must be complied with by Norte Energia. The Council also points out it has already agreed to reduce the size of the Ribeirinho Territory in negotiations with the company, as the area initially foreseen for expropriation was 32,000 hectares.

In its statement, the Council said that, despite the delay, the vast majority of families still intended to move to the Ribeirinho Territory. This includes a number of ribeirinhos who, before the project was approved, were resettled in Permanent Protection Areas already expropriated by Norte Energia. Some of these families have failed to adapt, however, and are waiting for the larger territory, as smallhold farming activities are not permitted in protection areas. Other families settled in such areas by the company did not even belong to traditional ribeirinho communities – yet the fact they abandoned the Permanent Protection Areas is cited by ruralists as evidence that the whole project is doomed to fail. “How, in the 21st century, can you settle a family in an area where they can’t dig a well or have house of bricks and mortar?” asked Siralta director Jorge Gonçalves, at the March 23 meeting, apparently unaware of the evident contradiction between his words and Siralta’s proposal that the Ribeirinho Territory be restricted to Permanent Preservation Areas.

The ribeirinhos also received further support from the coordinators of the Brazilian Society for the Progress of Science report. In a letter to the president of the Senate, Rodrigo Pacheco, of the Social Democratic Party, they expressed their “discomfort” over the external commission that Zequinha Marinho intends to lead. The letter emphasized that Ibama had approved both the Ribeirinho Territory and the role of the Ribeirinho Council, but “as yet, the Norte Energia Consortium has not complied with its requirements.” “We ask you and the honorable senators to make every effort to ensure the environmental licensing of Belo Monte complies with the law and provides for the reparation of the rights of the traditional peoples of the Xingu,” requests the document, signed by Sônia Magalhães and Manuela Carneiro da Cunha.

Delaying tactics

At a meeting with Aneel in December, Norte Energia representatives raised questions over the company’s own DPU request. The minutes of the meeting reveal discussions over the difficulties in negotiations with the landowners to be expropriated, and the admission that “some of the ribeirinho families” no longer want to go to the agreed Ribeirinho Territory. In response, Aneel made clear it was not the responsibility of the agency to analyze the merits of Ibama’s requirements for renewing the Belo Monte license. In addition, the Aneel representatives stressed, “the management of the acquisition of areas to meet its obligations is the responsibility of the agent [Norte Energia],” which must meet such requirements “through amicable negotiation or in the absence of an agreement, in court.” They also pointed out that the DPU, which is valid for five years, “can be complied with in part or in its entirety” – in other words, Norte Energia would not be obliged to buy all the land covered by the declaration, if some was not necessary.

On March 16, Aneel informed Norte Energia the analysis of the DPU request had been placed on hold, and gave the company ten days to make two corrections to the process. The requests are relatively minor: the insertion in the validation system of the vector data of the areas subject to the Declaration of Public Utility, and the signing off, by an authorized signatory, of the table summarizing the survey and status of these areas. Aneel did not respond when asked if these were the last pending issues prior to a decision.

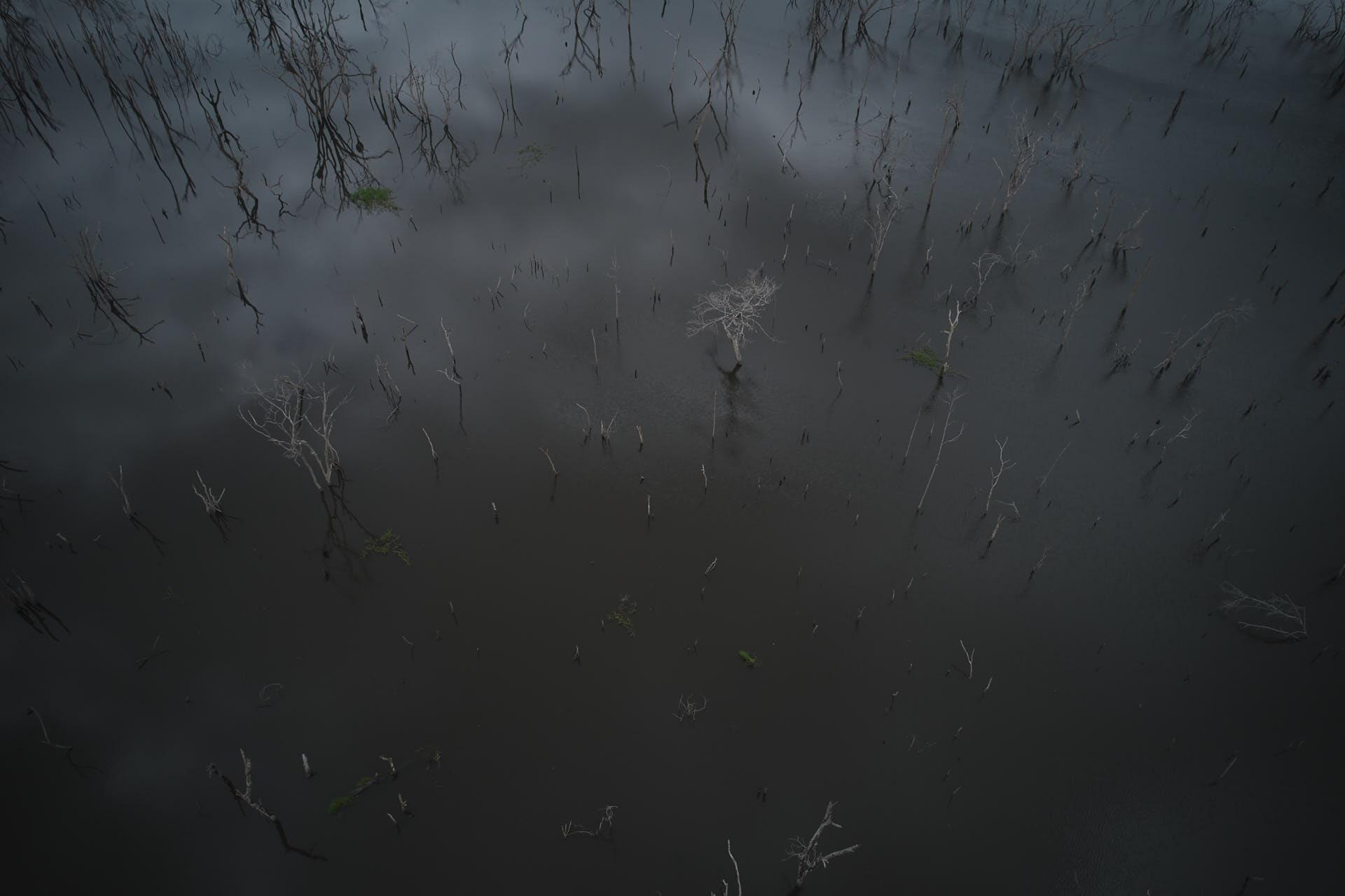

DEAD TREES MEAN THE LANDSCAPE AROUND THE BELO MONTE HYDROELECTRIC PLANT RESERVOIR, ON THE XINGU RIVER, RESEMBLES A GRAVEYARD FOR NATURE. PHOTO: PABLO ALBARENGA/SUMAÚMA

Since February, Ibama has demanded, in two communications sent to Norte Energia, that the company respond to a letter sent earlier that month by five non-Siralta linked landowners in the Ribeirinho Territory. In it, they said they had been contacted by Norte Energia two years previously, and had informed the company they would be willing to leave in return for compensation. They had made their farms available for an evaluation of their properties’ worth, but the company had gone quiet. “We have not received any response from them on the amount of compensation, nor a deadline for when we might receive it and leave our land,” they said, expressing their readiness for a quick sale.

Norte Energia only responded to the letters in April, but did not directly refer to the letter from the five landowners. Instead, it said it has been trying to buy land in the Ribeirinho Territory since last year, but “most of those consulted were opposed to the sale, or proposed values well above the market average.” As such, continued the company, it had to wait for the DPU to be issued by Aneel to “take the appropriate measures.” The company also claimed “the Public Prosecutor’s Office has opposed the purchase of separate parcels of land, as it supports the creation of a single territory.”

Even if it is true that the project demands a continuous, unbroken area of land for the families, given the importance of relations between neighbors in the traditional way of life, at no time has either Ibama or the Public Prosecutor’s Office said this would prevent available land from being purchased. On the contrary, the environmental agency stated the “acquisition (of land) in an amicable manner does not depend on the position of Ibama or Aneel” in its June 2022 report on pending requirements for the Belo Monte license renewal.

Norte Energia’s situation is to some extent comfortable, as it requested the renewal of the license prior to its expiry in November 2021, meaning the plant can continue to operate regardless of how long Ibama takes to make its decision. Asked if the company would be fined for the delay in taking action to implement the Ribeirinho Territory, the agency said “progress in this requirement is under analysis.”

Despite such buck passing, and difficulties that have lasted years, with some families living in a state of food insecurity, ribeirinha Francineide said she will not give up. “The territory will bring life in the midst of the violence, which is why we fight on, sometimes without even thinking about ourselves. The ribeirinho identity and culture must be respected from generation to generation, because we have always lived on the banks of the river, on the islands and creeks, since the world has understood itself as the world.”

Spell check (Portuguese): Elvira Gago

Translation into Spanish: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: James Young

Photography editing: Marcelo Aguilar, Mariana Greif and Pablo Albarenga

Maria Francineide Ferreira dos Santos travels the Xingu River, near where her house was flooded in Altamira. Photo: Pablo Albarenga.