Here’s a riddle: What’s a concept you hear about everywhere; nobody knows exactly what it means; but it sounds positive because it conveys a sense of life, so even those who profit from the destruction of Nature want to earn its seal of approval. The answer: the bioeconomy—literally, the “economy of life” and now a buzzword in public policy debates in Brazil.

It’s hard to ignore the bioeconomy: It is the subject of a plan launched by the Pará state government in 2022; it is one of six focuses in the Finance Ministry’s Ecological Transformation Plan; it features in one of the six missions defined by Brazil’s New Industry program, under the Ministry of Development, Industry, Commerce, and Services; and it is a target included in a Brazilian-proposal to the G20, made up of the world’s largest economies. While on a visit to Belém in late March, French President Emmanuel Macron, together with President Lula, announced a program to raise one billion Euros in four years (more than eight times the annual budget of the city of Altamira, Pará), which will be applied to the bioeconomy in the Brazilian Amazon and French Guiana, an overseas territory of France that neighbors the state of Amapá.

After nearly a year and a half of internal government negotiations, on June 5, World Environment Day, Brazil announced a decree that defines a National Strategy for the Bioeconomy. Two of the strategy’s goals are to expand “the market and income participation of Indigenous peoples, traditional communities, and family farmers” and promote development “grounded in the use of biological resources that are environmentally, socially, and economically sustainable.”

The decree provides for the creation of a National Bioeconomy Commission, drawn from both government and civil society, which will be tasked with drafting a National Bioeconomy Development Plan in just 60 days. The plan will define sector resources, actions, responsibilities, targets, and indicators.

Commission members will be appointed by three ministries: Environment and Climate Change, Development, and Finance. A National Bioeconomy Information System, under the responsibility of Marina Silva’s Environment Ministry, will be set up to support implementation of the plan. “The effort will be to take the various existing views of the bioeconomy and build an integrated government vision,” says Carina Pimenta, Bioeconomy Secretary for Brazil’s Environment Ministry.

It is easy to imagine the challenges involved in writing the decree and future plan, since the bioeconomy is a “disputed concept,” as several people interviewed for this report stated. “It’s like a huge narrative with many meanings, open to very different interpretations,” explains biologist Joice Ferreira, a researcher for 17 years with the Eastern Amazon unit of Embrapa, a state-owned agricultural research body, in Belém. “Some groups at a national level, for example, think the bioeconomy is anything that doesn’t rely on fossil fuel, anything that is planted. Anything that makes use of a renewable natural resource is considered bioeconomy, and sometimes the term is actually used as synonymous with ‘agriculture,’” Joice says.

One such example is a 2022 study by the Getúlio Vargas Foundation’s Observatory for Bioeconomy Knowledge and Innovation. Taking into account all sectors that rely on “renewable biological resources,” the study calculated the bioeconomy’s Gross Domestic Product—that is, the total value of goods and services produced by the bioeconomy. Among the sectors included in the study were agriculture, livestock, fishing, and all production of food, meat, paper, pulp, tobacco, and biofuels.

Cattle raised illegally in the Ituna/Itatá Indigenous Territory. Agribusiness monopolizes credit and claims to be part of the bioeconomy. Photo: Lela Beltrão/SUMAÚMA

Joice Ferreira has helped author documents on the bioeconomy produced by the Scientific Panel for the Amazon, established in 2019 by scientists from the eight countries that share the world’s largest tropical rainforest, plus French Guiana. “What really matters in this discussion?” she asks. “Coming up with a different economy that can respond to demands for a more sustainable present and future. If you have a particular monocrop that doesn’t make progress in terms of social concerns or better environmental practices, then what’s new about including old practices under the bioeconomy umbrella? What kind of progress is that?”

Before joining the government, Bioeconomy Secretary Carina Pimenta headed the Sustainable Connections Institute, or Conexsus, a nongovernmental organization that supports community businesses working to conserve endangered biomes. Carina, who negotiated the decree with 16 ministries, often speaks of “bioeconomies,” in the plural; the text of the decree in fact mentions “different segments of the bioeconomy” and “businesses adaptable to different scales and models.”

Carina says this can include some forms of energy generation using biomass (a generic name for organic matter or waste from crops such as sugarcane, eucalyptus wood, oils, bark and bagasse) and “low-carbon” agriculture. The 13 guidelines defined in the decree refer to biomass production not involving “the conversion of original native vegetation”—that is, deforestation—along with the promotion of “regenerative agriculture, productive restoration, the recovery of native vegetation, sustainable forest management and production, especially healthy food systems.”

The secretary says any and all activities that can be classified as part of the bioeconomy will be subject to these 13 “guiding principles.” The first of them talks about fostering activities “that promote the sustainable use, conservation, regeneration, and valorization of biodiversity and ecosystem services,” the last of these referring to services that Nature renders to humans, such as climate regulation. “You can’t stimulate economic activity in Brazil that will degrade our ecosystems,” says Carina.

An additional problem in this debate is the lack of any precise definition of what constitutes “sustainable.” The term “sustainable development” was given traction in the 1980s by the United Nations, which defined it as that which meets “the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” The UN 2030 Agenda divided this into 17 goals to be achieved in this decade, such as ending hunger and poverty and making “clean energy” accessible to all. But it is up to each country to define how to do this.

Socio-bioeconomy, a Brazilian term

In the Brazilian Amazon, this discussion has gained momentum because of the need to reinforce alternatives to the kind of businesses that “raze the forest” and are at present monopolizing credit, subsidies, technical assistance, and infrastructure investments, according to Ivanildo Brilhante, a native of Gurupá, Marajó Island, and director of the National Council of Extractivist Populations.

This regional debate draws from centuries-old knowledge held by Indigenous, Ribeirinho, Quilombola, and family farming communities and from the experience of the extractive reserves created over the past 30 years. In this century, often with technical support from ONGs like the Socioenvironmental Institute, Indigenous and Quilombola populations have begun selling their farm products and handicrafts to a broader public.

Family farmers in Tomé-Açu, Pará. An open letter by forest-people calls for technologies that respect their way of life. Photo: Oswaldo Forte/Fotoarena/Folhapress

Developed in this region, the concept of “socio-bioeconomy,” or “economy of socio-biodiversity,” reflects the idea that there is no forest without the people who live in it. The notion behind the term is that the Amazon’s “biological, cultural, and social diversity” must be “safeguarded and valorized,” as proposed in a 2022 article by a group of scholars led by Francisco de Assis Costa, who is with the Nucleus of Advanced Amazonian Studies at the Federal University of Pará.

In October 2021, at the Amazon Socio-biodiversity Meeting in Belém, extractivist, Indigenous, and Quilombola organizations released an open letter detailing their vision of the topic. “The socio-bioeconomy we defend is aligned with science and technology, with the purpose of enhancing the harvesting of forest and fishing products that allow us to process, store, and sell products of socio-biodiversity while respecting our ways of life,” the text reads. “We oppose innovation processes that result in packages […] fostered to replace native forest with monocrops of genetically uniform varieties to serve the food industry and then falsely publicized as environmentally appropriate systems.”

To give a practical example, the idea is to prevent what Ivanildo Brilhante calls the “açai-zation of the forest,” where incentives are centered on a few crops that have already conquered markets outside the Amazon.

The Landless Workers’ Movement, Brazil’s largest rural social movement, doesn’t use the term “socio-bioeconomy.” But in 2014, it set a formal goal of replacing agribusiness methods, like monocropping and intensive pesticide use, with “agroecology,” where food cultivation is conjoined with Nature conservation.

In one of their documents on the topic, the Scientific Panel for the Amazon defines the socio-bioeconomy. According to the text, the socio-bioeconomy covers activities that, among other things, “lead to the conservation and restoration of ecosystems,” “promote agroecosystems and diverse and integrated agroecological practices,” “protect human and territorial rights,” “add value locally to Amazonian products,” and “integrate scientific knowledge with Indigenous and local knowledge.” It lists as examples the “conservation and restoration of native forests with the aim of generating carbon and biodiversity credits,” “the cultivation, harvesting, and processing of native nuts,” “the harvesting of plants and oils for cosmetics and medications,” and “the cultivation of fruit in agroforestry systems and their processing for shipment in the form of value-added products.”

Farmer in Manicoré, Amazonas, holding a bottle of andiroba oil. Sometimes small innovations, like how oil is extracted, generate more income. Photo: Nilmar Lage/Greenpeace

Conversely, according to the panel, the socio-bioeconomy excludes activities that “lead to deforestation and environmental degradation,” “reduce river connectivity,” “promote monocrops, simplification, and unsustainable intensification,” “reduce biodiversity and compromise ecosystem services,” and “benefit only elites or privileged groups or increase social inequality.” This includes any type of mining, legal or illegal, deforestation for livestock raising, monocropping, large-scale biofuel production, and major hydroelectric dam projects, in addition to predatory fishing.

Amazonian economist and geographer Tatiana Schor heads the Amazon Unit of the Inter-American Development Bank, where she manages the Amazon Forever program, which has three funds worth a total of USD 349 million. The money is to be used over a period of five to seven years to provide grants, loans, and technical assistance for activities that reduce deforestation pressure. One of the accounts receives money from the UN’s Green Climate Fund and is earmarked exclusively for bioeconomy initiatives.

Tatiana says the word “socio-bioeconomy” has yet to catch on outside of Brazil and that there are challenges to not having a precise definition of “bioeconomy.” Bolivia, home to part of the Amazon, rejects the term, which it associates with large projects that turn all of Nature into merchandise. The same holds true for the Coordinating Board for Indigenous Organizations from the Amazon Basin, which has signed an agreement with the Inter-American Development Bank under which the economic activities of Indigenous peoples will receive support. As a condition for signing, the coordinating board demanded the text of the agreement not include the word “bioeconomy” but use “Indigenous economies” instead.

The absence of a firm definition notwithstanding, Tatiana says an essential principle of the bioeconomy is that it should be “positive for biodiversity.” As head of the bank’s Amazon unit, she commissioned a survey to ascertain how Amazon countries understand the bioeconomy; results of the study, which heard more than a thousand people, are now being compiled. “What I can say already is that in every country, there was a very strong idea that the bioeconomy means introducing innovative technologies into traditional processes,” she explains. This same emphasis can be felt in the Brazilian decree.

Joice Ferreira, from Embrapa, says innovations that make life easier for people who support themselves through activities compatible with environmental conservation in the Amazon aren’t always linked to the use of high-end technology. “For local populations, sometimes minor innovations—like how oil is extracted [from a nut or plant]—make a difference,” she says. The biologist also brought up the question of quality control of forest products. “People find it hard to achieve this control; they don’t do it consistently. So they can’t sell to the school lunch program because they don’t meet the minimum criteria,” she says.

One concrete case of innovation comes from the Santo Antônio do Tauá Mixed Agro-Extractivist Cooperative in Pará, whose products include murumuru palm nuts, sold to the Brazilian cosmetics firm Natura for use in moisturizers and shampoos. Gilson Santana, the co-op’s production coordinator, says the organization has designed a machine that cracks open murumuru seeds and extracts the nuts. “Before, it had to be done by hand, one by one. It would take a month to crack open a ton of seeds. Now it takes 50 minutes,” he says. The shells are used in boilers to produce steam energy.

Processing tucumã and murumuru fruit in Santo Antônio do Tauá. Photos: Gilson Santana/Camtauá

Greenwashing the ecological economy

Ricardo Abramovay, sociologist and full professor at the University of São Paulo Public Health School, has studied the relation between food production and the environment. When he was invited to co-author the chapter on the bioeconomy for the Scientific Panel for the Amazon, he looked into the origin of the term. Among other things, he discovered that tropical rainforests were not cited in the scientific bibliography on the topic. “Even in Latin America, the term is associated with renewable fuels and biomaterials, green plastic. What’s worse, there are no critical considerations about where the raw materials come from. So corn for making ethanol becomes part of the bioeconomy,” he says, in reference to monocrops that deplete the soil through intensive use of water, fertilizers, and pesticides.

Abramovay argues the bioeconomy should be considered an “ethical-normative value”—as he defines it, a kind of relationship between society and Nature wherein the production of goods and services does not destroy the environment. For this reason, he says, the product matters less than the way it was obtained. “You’ve got an economy of life or ecological economy when economic activities try as much as possible to regenerate the soil, respect the lives of animals,” he explains. Abramovay gives an example: poultry and pig farms “where the term ‘torture’ wouldn’t be an exaggeration” cannot be part of a bioeconomy.

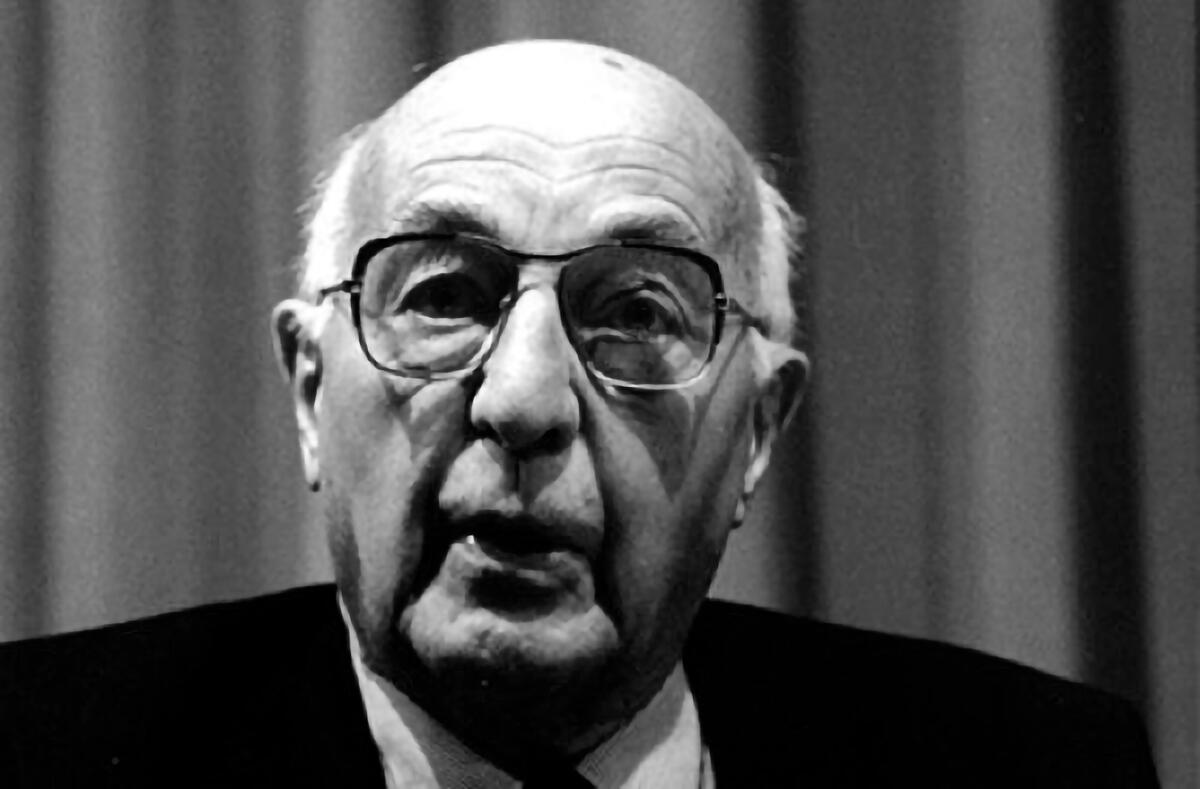

The concept of ecological economy was developed in the 1970s by Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen (1906-1994), a Romanian-born professor residing in the United States after World War II. Rediscovered recently, when the climate crisis grew more evident, Georgescu-Roegen stressed the economy cannot be detached from the limits of Nature, as traditional economists do. To simplify a complex theory, he said using Nature in pursuit of unlimited economic growth would eventually exhaust the foundations that sustain life—and the organization of the very economy.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen, o romeno que forjou o conceito de “economia ecológica”. Foto: Reprodução da internet

Since then, the word “bioeconomy” has been used mainly in materially wealthy countries, but in ways quite different from what was originally intended. Articles on the subject by Brazilian researchers often cite a 2016 study led by Markus Bugge, a Norwegian at the University of Oslo, who boiled the bioeconomy down to three aspects, which now generally predominate: biotechnology, bioresources, and bioecology.

In the case of biotechnology, the focus is on making products, such as vaccines or medicine, from plants and animals. In the case of bioresources, the concern is with the cultivation and processing of biomass for the manufacture of biofuels, biodegradable packages and plastics, and even furniture. While the concept “bioresources” extends to activities like recycling, only bioecology—according to this interpretation—is premised on conservation and the sustainable use of biodiversity. In the other two cases, the process that leads to the final product doesn’t matter much—contrary to the view espoused by Abramovay.

Emphasis on technology

In the decree announced on World Environment Day, an emphasis on technology can be felt in the very definition of bioeconomy as a “model of productive and economic development based on values of justice, ethics, and inclusion, which can efficiently generate products, processes, and services, based on the sustainable use, regeneration, and conservation of biodiversity, guided by scientific and traditional knowledge and related innovations and technologies, with a view to adding value, generating jobs and income, sustainability, and climate balance.”

In its guidelines, the decree talks about promoting “bio-industrialization,” expanding innovation based on biodiversity and agriculture, and fostering research to “conjoin scientific and traditional knowledge.”

Bioeconomy Secretary Carina Pimenta defends the plan’s emphasis on biotechnology. “The frontiers of knowledge in the bioeconomy are very much linked to knowing more about our biodiversity, new drugs, new uses for cosmetics, the functions of a given foodstuff, and the genetic engineering behind improved crop yield,” she says. “This has to be part of policy as much as a vision of the sustainable production of açai, Brazil nuts, or baru nuts.”

By making it a goal to boost the competitiveness of Brazilian biodiversity products “in the transition to a low-carbon economy,” the decree opens the way for considering some forms of biofuel production as part of the bioeconomy. In Brazil today, this production revolves mainly around monocrops, such as sugarcane and palm oil. But the text does not specifically mention the word “biofuels,” which the Lula administration is betting on for the energy transition in the realm of transportation.

This contrasts with discussions within the G20, chaired by Brazil this year. In a concept note on the bioeconomy presented to the group, the Brazilian government says biofuels have potential as a “sustainable solution” not only for cars but also for air and sea transport. One of the obstacles to an agreement within the G20 is the absence of any international consensus on just how green biofuels are, something the Lula administration sees as reflecting the commercial interests of countries now investing in other alternatives to oil and gas. At international meetings, Environment and Climate Change Minister Marina Silva has argued that biofuel production can be sustainable in Brazil and does not harm food crops.

Brazil’s proposal is that G20 countries come to an agreement about “top-level principles” of the bioeconomy to help define which activities fall within its domain. If an understanding is reached, the topic will feature in the final declaration by the group’s presidents and prime ministers, who will meet in Rio de Janeiro in November. With this, Lula hopes to attract investments in these activities.

Sugarcane cultivation in Ribeirão Preto. Despite their reliance on monocropping, biofuels are at the center of the bioeconomy debate among G20 countries. Photo: Ricardo Benichio/Folhapress

Who gets what piece of the pie?

When so many sectors show an interest in being part of the bioeconomy, there is a fear that the most powerful will yet again enjoy the biggest piece of the pie. The decree stipulates the National Bioeconomy Development Plan should define how it is financed and refers to the creation of instruments to this end. But this all depends on which activities are ultimately included—and the mention of the government’s agricultural policies as one of the bases of the plan could open a loophole for traditional agribusiness.

Bioeconomy Secretary Carina Pimenta says she is endeavoring to ensure there are no disputes between the different bioeconomies. “The plan will break down into a number of sectors, with a set of implementation instruments,” she says. “Then we have to make sure sector plans have specific instruments, so one part of the bioeconomy doesn’t compete with others. And so we don’t call everything the bioeconomy, but only strengthen one type.”

Today, the ministries of the Environment and Climate, of Agrarian Development and Family Farming, and of Social Development and the Fight against Hunger are working on the sector plan for the “economy of socio-biodiversity.” The idea is to begin implementation by selecting territories where it is possible to expedite the solution of such issues as infrastructure, technical assistance, funding, and land tenure regularization and enrollment with CAR, the national environmental registry.

Attorney Sergio Leitão, one of the founders of the Socioenvironmental Institute, is now the executive director of Instituto Escolhas, a not-for-profit think tank focused on sustainable development. Since 2019, the institute has undertaken and commissioned studies on the generation of jobs and income in activities that can be classified as part of the bioeconomy. Their studies have, for example, concluded that recovering one million hectares of degraded forests in Permanent Preservation Areas located within agrarian reform resettlements could create over 238,000 jobs in the implementation and management of agroforestry systems. Or that the recovery of 12 million hectares of deforested forests—Brazil’s official target for 2030—would generate more than five million jobs in forest management and seedling production.

“Our concern has to focus on lending substance to the concept [of bioeconomy], [and of having] effective proposals that will enable us to make a good argument,” Sergio says. “A good argument means having proposals that show the government, investors, and public and private banks that this activity can reduce poverty, improve the living conditions of traditional populations and Indigenous peoples, but also [provide] a real, concrete chance of creating new economic possibilities in the Amazon region, in the Cerrado, in all of Brazil’s biomes,” he says.

Sergio points out that stimulating the bioeconomy could benefit not only forest-peoples but also the “guy who holds the chainsaw,” that is, people in towns in the interior or in marginalized areas of large cities in the Amazon who don’t have jobs or income. “You take deforested areas around these cities, and you have to recover them. This will generate jobs,” Sergio says.

An airplane spreads pesticides over a soybean plantation in Bahia. Açaí being harvested in Barcarena, Pará. Photos: Marizilda Cruppe/Greenpeace & João Laet/SUMAÚMA

Will the socio-bioeconomy be the Amazon’s salvation?

But can socio-bioeconomic activities really compete with the businesses now destroying the Amazon and the Cerrado—businesses that have strong political backing?

In the case of agriculture, another study by Instituto Escolhas found that in northern Brazil in 2022, this activity received BRL 5.9 billion (USD 1.15 billion) in tax cuts or exemptions from the federal government and BRL 4.4 billion (USD 852 million) in subsidies, which is when the government covers certain expenditures within a given economic sector. Agriculture in the region collected a further BRL 9 billion (USD 1.74 billion) through the Constitutional Financing Fund for the North, 76% of the fund’s total allocation.

A study by specialists at the Brazilian Development Bank, BNDES, showed that from 2017 to 2021, nearly 88% of money disbursed by the bank for agriculture in the North went to livestock raising, pine plantations, soybeans, and other monocrops, for a total outlay of BRL 156 million (USD 29 million) for the period. “We’ve been saying the bioeconomy or socio-bioeconomy needs neither more nor less than agriculture. It just wants the same treatment,” according to Sergio Leitão.

Compare these figures, for example, with the funding received by different community activities in Pará through the Inova Sociobio project, financed by the UN Development Program and the Norwegian government. Through a competitive tender, the National Council of Extractivist Populations won grants for three projects in Oeiras, Curralinho, and Gurupá, each in the amount of BRL 100,000 (USD 20,000). The money was used to create a seedling nursery for reforestation purposes, an açai pulp processing center, and a workshop that will use leftovers from a forest management project (the latter will enter operation once power has been hooked up). “We worked a collective miracle to get these investments,” says Ivanildo Brilhante, of the national council.

Ivanildo drives home the importance of having more money and more staff devoted to accelerating land tenure and environmental regularization in community territories, a prerequisite for access to bank credit and the licensing of economic activities. Many communities are currently unable to add their land to CAR, the national environmental registry of rural properties, because they can’t afford to have their land surveyed. They often outsource the job to a company and in exchange agree to sell their products on disadvantageous terms.

“We also need credit that takes the basket of socio-biodiversity goods into account,” Ivanildo says. “This means fishing, seeds, oils, fruit, vines, resins, handicrafts. There’s credit to finance açai, but it won’t be long before we’re açai-zing our forests. There’s credit to finance Brazil nuts but we can’t have just Brazil nuts,” he says. “In livestock, the cattle themselves are the collateral. In our case, the collateral could be the regional basket of goods that was financed.”

Tatiana Schor, with the Inter-American Development Bank, sees “three scales” to the Amazon’s socio-bioeconomy. The first consists of protected Indigenous and traditional territories, sites of a developing niche economy that requires support but where excessive growth would disrupt cultural processes and integration with Nature. The second scale is that of products, such as Brazil nuts, that have already entered larger trade circuits but where the producer gains the least. “The weakest link in this chain is production, whether it’s extractivism, family farming, or rural workers. This has to be fixed, because there’s no point in scaling up this product if we still have the rural poverty we see in the Amazon,” Tatiana says.

The third scale, according to Tatiana, can be divided in two. One encompasses products that are already on large markets but need to adopt elements of biodiversity conservation, such as açai. “We know we won’t be able to do this 100% on açai plantations, but we can work with different species, raising bees to produce honey in agroforest systems,” she says. This third scale also entails technology that enables the processing of socio-biodiversity products, thus adding value to them.

Tatiana, however, doesn’t think the bioeconomy alone will be able to respond to economic pressure from the sectors now destroying the rainforest. That’s why she has made the creative economy—art, festivals, tourism, gastronomy, fashion, architecture, and design—part of the program’s focus for the Amazon. “This is what really generates jobs in the Amazon today,” Tatiana argues. Data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics, cited by the project Amazônia 2030, show that more than 80% of jobs in the region are located in urban areas, and 46% are in the service sector.

Sergio Leitão points out that a large share of socio-bioeconomic activities in the Amazon, whether practiced by traditional communities, family farming, or private companies, should not be thought of as big business. “We can say that bioeconomy businesses in the Amazon will be big when added up, in other words, businesses themselves may be small, the scale of logistics is different. But this doesn’t make the sector small overall, because it’s the sum of small businesses,” he says.

What must be done, adds Sergio, is to tackle the obstacles standing in the way of business potential, such as the lack of technical assistance and electrical, communication, and transportation infrastructure adapted to varied, geographically scattered activities. Sergio says federal and state public banks have “idle” money that they don’t loan out to bioeconomy activities because their protocols are only designed for dealing with traditional businesses—many of which destroy Nature. Only now, for example, have the agricultural research body Embrapa and the National Development Bank devised indicators to evaluate funding requests for agroforests and forest restoration. “If we don’t resolve the bottlenecks in the standing-forest economy, the dispute [over resources and priority] might remain in the field of rhetoric,” he warns.

Environmental monitoring in the Paquiçamba Indigenous Territory, Pará. Traditional knowledge about Nature is a focus of the decree. Photo: Soll/SUMAÚMA

The fight for fair compensation for traditional knowledge keepers

When it comes to incentivizing the use of Brazilian biodiversity in the manufacture of cosmetics, medicine, food, and other products, a main concern is ensuring the populations who have traditional knowledge of the properties of plants and animals of the Amazon rainforest and other biomes actually receive their fair share of earnings from the commercial exploitation of this wisdom.

To address this, the 2015 Biodiversity Law must be effectively enforced. This law, which is referenced in the decree that created the National Strategy for the Bioeconomy, regulates the research and development of products using the genetic heritage of Brazilian species and traditional knowledge and calls for benefit sharing. The law created a database: the National System for the Management of Genetic Heritage and Associated Traditional Knowledge, known as SisGen. Since November 2017, it has been mandatory to register in SisGen all research or product development that uses Brazilian species.

Nevertheless, a study by Instituto Escolhas found that, by the end of 2022, 87% of the 150,538 studies recorded in SisGen only documented genetic heritage and did not identify associated traditional knowledge. Among the 13% that did report their reliance on traditional knowledge, the majority did not say which people or community held the knowledge. Of the 19,354 entries related to finished products, only 9% reported using traditional knowledge.

Instituto Escolhas sees these numbers as evidence of the theft of traditional knowledge. “One example […] is the Amazonian giant leaf frog (Phyllomedusa bicolor) whose secretions are used as medicine by many Indigenous peoples in the Amazon. The substance has 11 registered patents in countries like the United States, Canada, Japan, France, and Russia,” the study points out. It suggests creating a database specifically for traditional knowledge to facilitate cross-checking information.

The Genetic Heritage Management Council, under the Environment and Climate Change Ministry, created a technical board in March to devise solutions to this problem. According to Bioeconomy Secretary Carina Pimenta, the ministry has also been working since 2023 to launch the National Benefits Sharing Fund, which was foreseen under the 2015 Biodiversity Law but never implemented.

Brazil is a signatory to two international treaties on the utilization of biodiversity that provide for benefits-sharing: the Nagoya Protocol, an agreement under the UN Convention on Biological Diversity, and the Treaty on Intellectual Property, Genetic Resources and Associated Traditional Knowledge, which was finalized in May by the World Intellectual Property Organization.

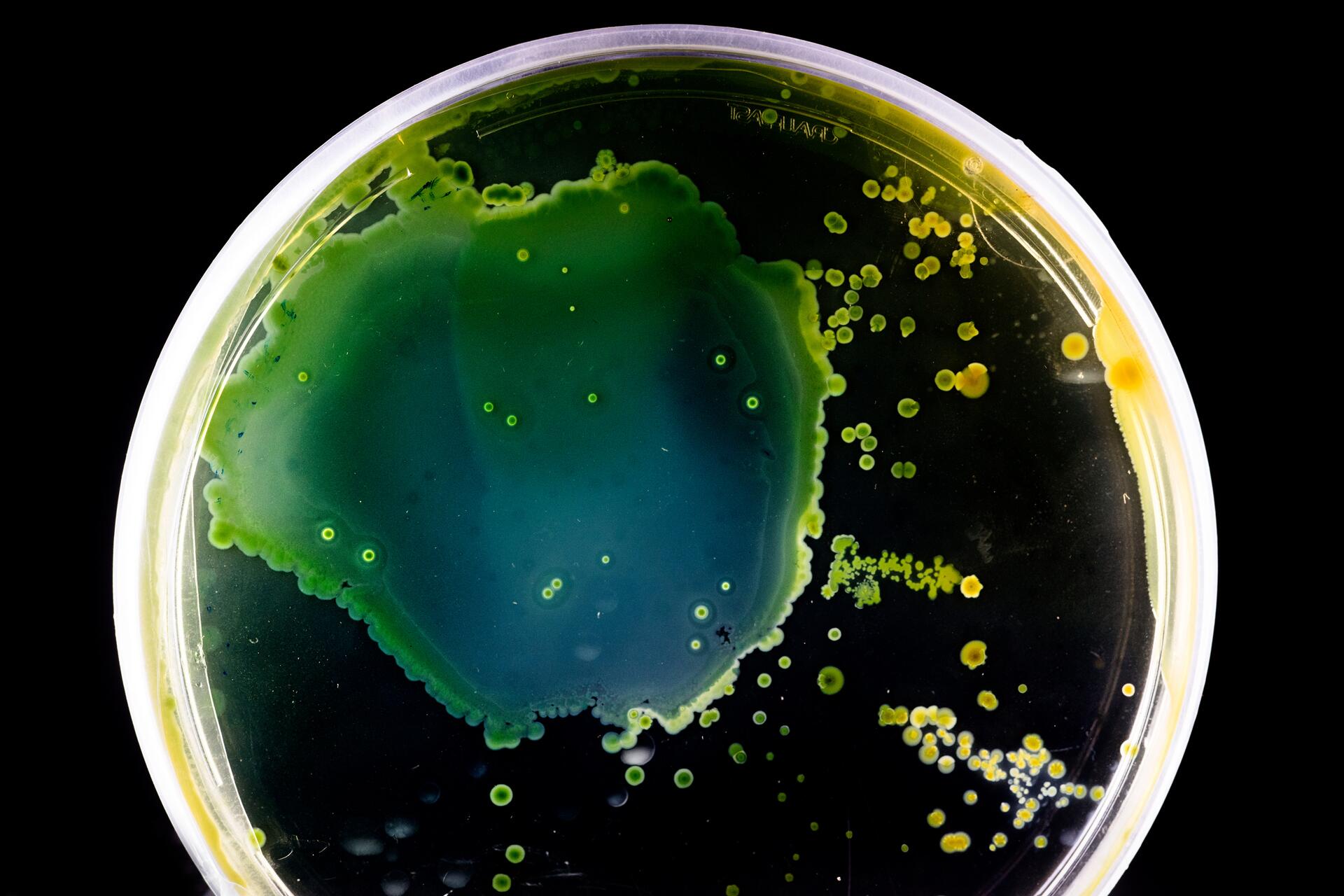

Amostra de bactéria colhida nas águas do grande recife do litoral amazônico. A “biotecnologia” tem peso significativo na estratégia do governo. Foto: Marizilda Cruppe/Greenpeace

Report and text: Claudia Antunes

Editing: Talita Bedinelli

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Fact-checker: Douglas Maia and Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Spanish translation: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Diane Whitty and Maria Jacqueline Evans

Copyediting and finishing: Natália Chagas

Editorial workflow coordination: Viviane Zandonadi

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum