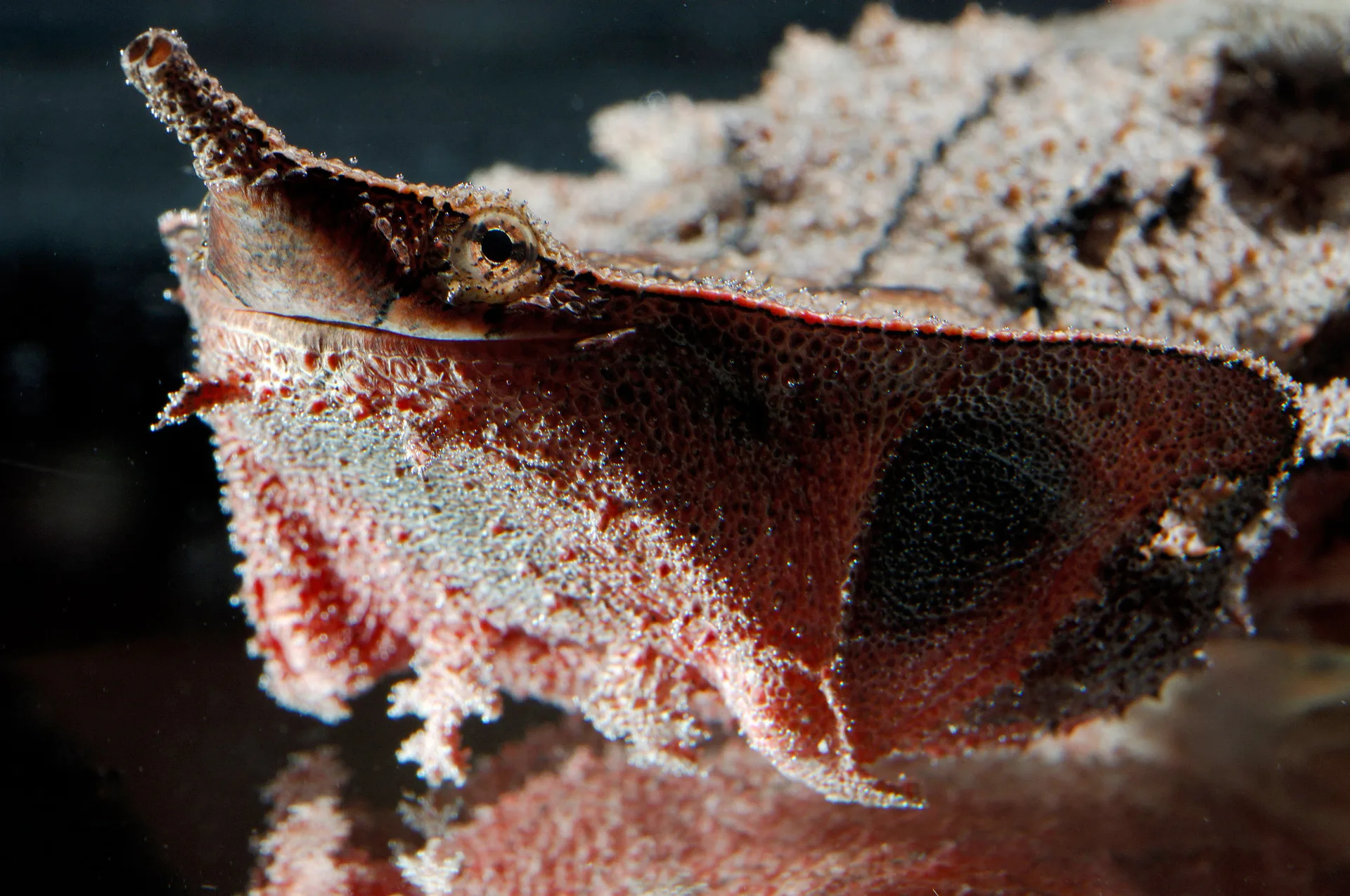

They could be dragons emerging from a suit of armor, snakes seeking shelter under a rock shell or a pile of dead leaves at the bottom of a river. “Ah, the ugly one,” said a lady when she saw it in a tank on the outskirts of Leticia, in the Colombian Amazon. “Matamata guitar,” says Elizabeth Pérez, a 52-year-old indigenous woman who monitors the consumption of this species of turtle in the Paujil marketplace in Puerto Inírida. He spends his time at the bottom of the rivers keeping watch, she says. He takes care of the lord of the waters and sings.

Little is known about Matamata turtles (Chelus fimbriata). They are found in nine countries, in an area covering almost 40% of South America, but we do not know how many there are; there is no estimated figure. Nor do we know what their main predators are, or even the origin of their name. Some say that it comes from the Tupi-Guarani mata matá, “kills a lot” , and that it refers to the turtle’s predatory capabilities, since it feeds exclusively on live fish and crustaceans. Others speak of a possible adaptation of raparapa, the name in Sranan Tongo, the language of the Guianas, first mentioned in the mid-eighteenth century by the French naturalist Pierre Barrère, but the word does not seem to have a clear meaning.

It belongs to the Chelidae family and has its roots in Gondwana, the supercontinent that grouped together South America, Australia, Arabia, Africa, Antarctica and India. They are the only survivors of the genus Chelus, from the Greek meaning “turtle” or “tortoise” or “lyre”, due to being the main material from which the instrument’s case was made. Their distant ancestors are as old as the first dinosaurs and predate crocodiles, mammals and flowers. Their closest relatives witnessed the final rise of the Andes Mountains, the delineation of the Amazon River and the extinction of saber-toothed tigers, giant sloths and the rest of the megafauna.

They haven’t changed much since those times, according to fossil records. They appear to have a perpetual smile beneath their beaks, a snorkel-shaped nose for breathing in low water, and protuberances on the lower face that look like sea beards, or naff mustaches. Their face is flattened and triangular, similar to that of a run-over rattlesnake. The largest ones have shells little more than half a meter long, although in the Amazon there are stories of huge specimens which unsuspecting people have stood on, mistaking them for rocks. Their neck is almost the same length as their shell, so, unlike other turtles, it is impossible for them to hide their head. They protect it by folding it horizontally under their armor and then extending it, suddenly, when hunting. Day and night they powerfully suck in fish and animals that approach them thanks to a powerful hyoid apparatus —the set of bones that encase the neck and jaw— and a distensible esophagus. That suction is the only sound they make, or at least the only one we have been able to detect (other turtles make all kinds of noises: the barking of the velociraptors in Jurassic Park is in fact the sound of tortoises having sex).

They prefer swampy, slow-moving streams, but also inhabit turbid rivers and sewage canals. We do not know how long they live, but, like other turtles, they have a long lifespan, which may exceed 70 or 100 years.

“Turtles don’t really die of old age,” Christopher Raxworthy, associate curator of herpetology at the American Museum of Natural History, told the New York Times; if it weren’t for someone eating them, or viruses and bacteria, they might just live indefinitely.

It is also not very clear who eats them. Giant otters have been observed attacking them, and giant tegu lizards have been observed raiding their nests, but we cannot point to them as the essential diet of a particular species. Some people believe that they may serve as food for jaguars and crocodiles.

Some communities in the Amazon and the Orinoquía region have been eating them for centuries, although it is a sustainable form of consumption, according to the Amazonian Scientific Research Institute SINCHI. Most people leave them alone. They are hard to see unless the waters have receded, their stillness and plant-like appearance make them almost invisible. If someone comes across them and they feel threatened, “they raise their tails and let out a disgusting fart,” according to biologists Carlos Lasso and Mónica Morales, who have studied them. They are reptilian skunks without the fur and face of mammals to redeem them.

Despite the above, they are becoming increasingly scarce, or at least that is what is believed, since there is no data on the size of their populations globally or by country. In part, this is due to habitat destruction, the climate crisis (in sea turtles, the temperature at which the egg hatches determines the sex of the hatchlings, while in river species, it seems to affect behavior) and the other usual suspects: changes in land use, pollution and the introduction of invasive species. But in the case of Matamatas there is an additional factor: collectors in the United States, Europe and Asia are willing to pay hundreds of dollars for each specimen. They can be purchased when they are just a few weeks old, a couple of years old or already adults.

Only Peru sells them legally. Until 2015, a couple of thousand Matamatas were exported each year, as a permit from the National Forestry and Wildlife Service (SERFOR) was required to breed them and take them out of the country. That year, however, a law was passed that eliminated that requirement. Since then, Peruvian hatcheries, reinforced by Colombian traffickers, have shipped more than 60,000 Matamatas to fill the aquariums and vanity projects of hobbyists around the world. In a short period of time, it became the second most exported turtle in Peru, after the Yellow-spotted river turtle, or Taricaya (Podocnemis unifilis).

The problem is an old one: “Turtles are the most exploited and abused animals in the world,” the authors of the book Turtles of the World write. In 2011, Hong Kong authorities detained a shipment of 11,000 turtles of eleven different species, reports writer Sy Montgomery in her book Of Time and Turtles. Four years later, in the Philippines, 3,800 individuals of Siebenrockiella leytensis, a critically endangered freshwater turtle species endemic to that country, were seized.

It is an irresistible business for traffickers: on the black market, a Yunnan box turtle (Cuora yunnanensis) can cost $200,000 dollars and Chinese three-striped box turtle (Cuora trifasciata), $25,000, to give just two examples. Matamatas are cheaper —their price ranges from $250 to $1,000— but the volume of demand, and the poverty of our countries apparently make them worth the effort.

We know little about these turtles, but with the information available, it is clear they face three main scenarios. What follows are three life stories that are quiet, turbulent or unfair, depending on how you look at them. Together, these stories changed the world, leading to the discovery of transnational trafficking networks, the identification of a new species and the creation of genetic protocols, police alliances and a planetary convention to stop their extermination.

I

It starts with an egg. Or, rather, it starts with three eggs in three different nests. For now, we will focus on one of them. A lone female buried it in 2014 on a sandy beach in the Colombian Orinoquía region along with at least half a dozen others, in around September or October, the time when the rainy season ends and the waters begin to recede (the Sikuani indigenous people call October the month of the Matamata, which they call atzapani). In that first nest, the spherical eggs, 35 mm in diameter, almost the size of ping pong balls, incubated for almost 200 days away from the claws of lizards, dogs and other predators, until one day a person started digging around them.

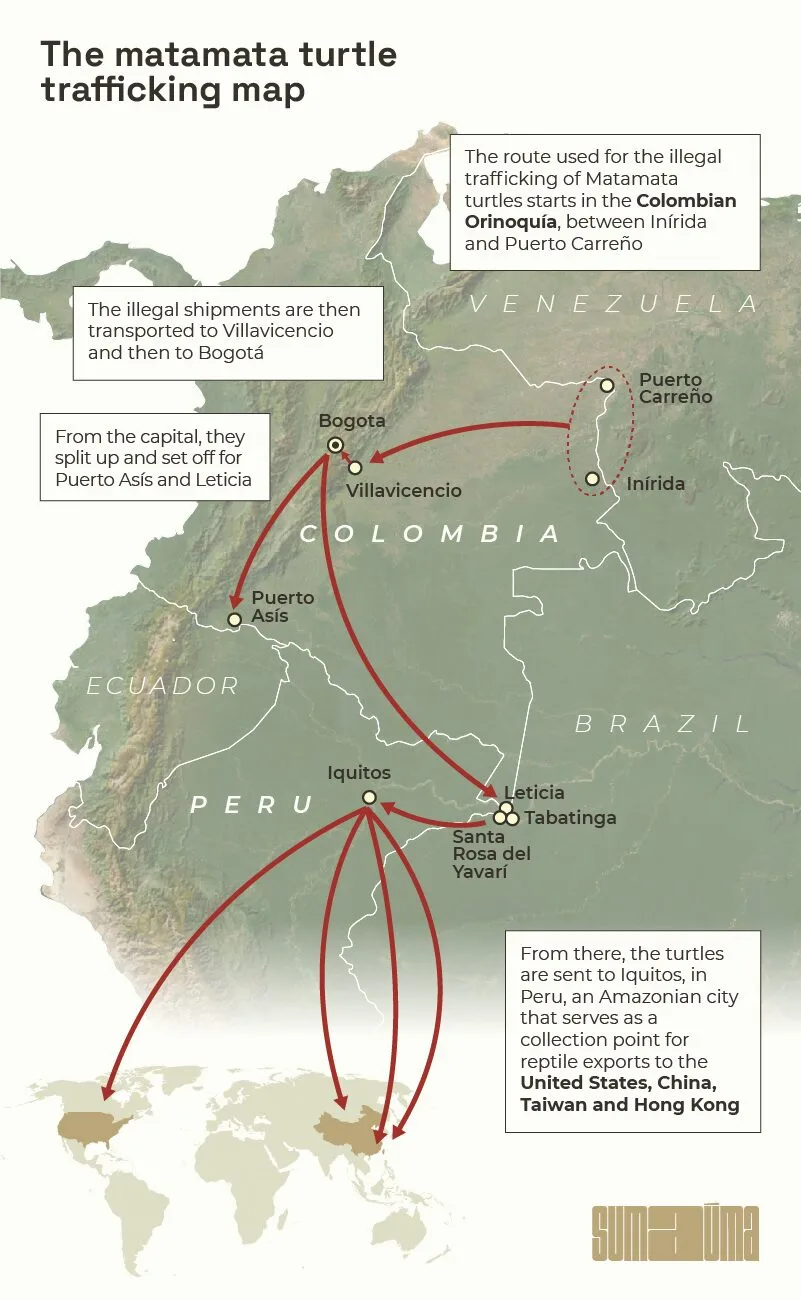

The plunderer took the eggs from the first nest, including one in particular, the one we are talking about. It is not known who transported this and the other eggs to Bogotá, or if they finished incubating them in Puerto Inírida or Villavicencio. Perhaps, they waited for them to hatch and immediately loaded the hatchlings onto a plane. However, the environment must have been completely alien to the Matamatas from the first nest, which this first story is about.

This is an ultra-resistant species, Daniel Alonso Pardo, a veterinarian who, as director of the Ikozoa Bioparque Amazónico Foundation, watched over the thousands of hatchlings that were seized at the Leticia airport between 2019 and 2020, told me. The few deaths he recorded were due to sudden changes in temperature. They would get hypothermia and at dawn, they were dead.

An X-ray of a Matamata turtle registered by the Ikozoa Bioparque Amazonas Foundation. The species belongs to the suborder Pleurodira, commonly known as Side-knecked turtles. Credit: Cortesy of Fundación Ikozoa Bioparque Amazonas

When the Matamata from the first nest was transported, its shell was only two or three centimeters long. It was a miniature version of its parents. The main difference was its color: it did not have the brown, ochre and dark brown tones of the adults, but a shade between red, orange and pink similar to that of raw beef, the shell of certain crabs or a kind of salmon. At just a few days old, it already had five small, well-formed claws on its front legs and four on its hind legs. The scar of the umbilical cord that joined it to the egg wall could be recognized in the middle of the plastron, the lower part of the shell structure (the scar disappears after a few weeks). And it was even more attractive than the adults of her species, or, at the very least, even more unreal. “They’re ugly cute,” Monica Morales, a turtle biologist who studied the natural history of Matamatas, told me.

To prevent it from dying in transit, they may have tried to raise its temperature by wrapping it in newspaper, sawdust or some other cheap material. On the occasions when authorities have managed to seize them, they have been found in cardboard boxes of Chilean apples, under shipments of fingerlings for fish farming projects, or in shipments of ornamental fish.

The Matamata turtle that left that nest in the Colombian Orinoquía region may have died en route due to temperature changes, but, for the sake of our story, let’s assume that it did its species proud and somehow survived the journey. It probably arrived in Leticia in a DC-3 cargo plane, camouflaged in a parcel or in a shipment of fish. Someone picked it up on time along with its brothers and sisters —it is difficult to distinguish the sexes at a glance, but males tend to be a little smaller, have slightly longer tails and more concave plastrons— and crossed the border without difficulty.

That is the easiest part of the journey for traffickers. Leticia, the capital of the Amazonas department, is located on the border with Brazil and Peru. In mid-June, I visited the city and, in under 20 minutes, walked from Colombia to Tabatinga in Brazil, and then crossed the river by boat from Colombia to Peru. There are no border controls and the trip to Santa Rosa, the Peruvian town on the other side of the Amazon River, costs just over a dollar. The boatman who took me, a Putumayo Indian named Antonio, had a pet Matamata in his house and offered to get me one, if I was interested.

After leaving Leticia, the turtle probably went down the river to Iquitos, in the Peruvian department of Loreto. Boats leave three times a week, cost about $40 and take about 18 hours to reach their destination, a relatively short trip. The main exporters of fauna in Peru are located in this department. There, the Matamata from the first nest was mixed with those bred in the hatchery to which it was sold. It was different from the others, but that shouldn’t have mattered. Matamatas rarely interact. In captivity, males and females recognize each other and make synchronized movements in the water when they are about to mate —their sexual maturity occurs at around five to seven years of age—, but beyond that they seem to ignore each other, especially at a young age. So the turtle sat motionless in its pond for quite a while. It was fed and cared for, we have no idea whether well or badly, until an order arrived from Hong Kong, China —presumably an intermediary according to experts—, Taiwan or the United States, the main clients of Peruvian companies. It was packed onto a plane again, this time more carefully, and flown to an aquarium.

Its price increased exponentially. According to Major Christian Hair Mesa, head of the Colombian National Police’s Natural Resources and Environmental Crimes Investigation Unit, the person who dug up the eggs in the Orinoquía region got paid between $5,000 and $10,000 pesos (between $1.25 and $2.5 dollars) per turtle; the traffickers in Leticia were paid between $20,000 and $30,000 pesos ($5 to $7.5 dollars), and the buyers in Tabatinga or Santa Rosa, between $30 and $40 dollars. The price for end customers —collectors and home aquarium owners— is 6 to 25 times more than those last figures.

It is very easy to buy them. There are several distributors in the United States. I recently wrote to five of them to ask about their specimens. They offer to ship them in less than a week with all possible care to any part of the country and special aquariums can be purchased to keep them. Water should be changed often to avoid diseases, the pH kept between 5 and 6, and the temperature around 30°C, say their owners in specialized forums. They may have skin irritations or suffer from respiratory infections when there are many dissolved organic substances in their new home. One of the stores wrote to tell me that they had Orinoco Matamatas available.

If it found a good owner, the Matamata from the first nest should still be alive. It is probably doing very little, as they do not interact that much with humans. Some turtles seem to be able to recognize people and come when called. Matamatas, at best, learn to associate people with food, according to the Mata Mata Turtles Pet Owner’s Guide, a 2017 handbook for owners and prospective buyers. (One of the sections includes some of the beliefs about the animal: “Matamatas are reptiles, so they don’t suffer or feel pain”).

Its life is spent in that aquarium, ideally at least 300 gallons in volume and with ample space for it to walk around, according to comments in the forums. Today it would be nine years old, which is young for a turtle. Some of the owners raise fish —tilapia, guppies, carp, swordfish or goldfish— in order to feed them live food. Others try to get them used to the turtle concentrate sold in pet stores, which is not recommended, and some may survive. Most of the time they remain motionless until they are given food. They are decorative objects in tanks, like piles of dead leaves without any trees in sight.

Leticia, on Colombia’s border with Brazil, is one point of departure for Matamatas abducted by traffickers. Photo: Juancho Torres/Anadolu Agency via AFP

II

The Matamata from the second nest is dead. It hatched from its egg and died in 2015, on its way to Leticia; it is not known exactly why. Like the one from the first nest, it was almost the size of a paper clip, salmon-colored and still had the equivalent of a navel in the middle of its plastron. It arrived in Bogota on a fast flight from Villavicencio and then left on another flight to Leticia. But the similarity in their paths ended there. The turtle was unable to withstand the demands of the journey. Its death, however, produced a revolution for its species.

In Leticia, the police arrested the person who picked it up. He transported it by motorcycle in a padded box, in deplorable conditions. The cop delivered it along with hundreds more tiny Matamatas to Corpoamazonia, the government institution in charge of regulating and protecting the natural resources of southern Colombia. The authorities thought they were part of the local population, but were puzzled by the fact that they had traveled from Villavicencio.

By chance, on June 19, 2015, an ichthyology conference had ended in Leticia. One of the assistants was Carlos Lasso, the biologist who had worked with Monica Morales in Vichada. At the age of 14, his family left Spain and moved to Venezuela. In Caracas, Lasso studied biology at the Central University. He then did a PhD in Seville, with a thesis focused on fish from the plains of Apure, in western Venezuela. There he managed a biological station and met Manuel Sánchez-Villagra, a student researching the Chelus genus of turtles. Like other naturalists and researchers before them, Lasso and Sánchez-Villagra suspected that there were two species of Matamata, as there were marked morphological differences between those of the Orinoco and those of the Amazon. The color of the neck, the shape of a carapace plate and the abdominal surface varied from one to another. The discrepancies were not marked enough to be sure that they were two species —think, for example, of the morphological differences that exist in different breeds of dog— but Lasso and Villagra were convinced that all they needed was more evidence.

Lasso finished his work in Apure and, after the crisis that caused the collapse of Venezuela at the end of the 2000s, he moved to Colombia, where he began working with the Humboldt Institute. With Monica Morales he captured and analyzed the movements and diets of the Matamatas in 2013, in Vichada. Five of them were fitted with trackers and followed for more than a year (they moved very little). Several others were captured and made to vomit in order to study the contents of their stomachs (they had mostly half-digested fish and shrimp).

By the time of the conference, Lasso was particularly fond of the species. His reunion with the turtle had also rekindled his desire to demonstrate that the differences between those of the Orinoco and the Amazon were not merely superficial. For this reason, he had recently asked a student from the National University based in Leticia to help him obtain samples for genetic analysis of the Matamata from the two basins.

Leticia is a small city —of about 50,000 inhabitants— and the student was quick to learn of the seized turtles in the hands of Corpoamazonia. It was the early morning of June 20, a Saturday, but they knew Lasso was traveling back to Bogota that same day, so they did not hesitate to call him. After hearing the news, Lasso contacted Susana Caballero, a biologist and professor at the University of the Andes with whom he collaborated on genetics. As fate would have it, she was also in town for the conference.

They got ready in a hurry, and rushed to see the turtles. They arrived at seven o’clock in the morning. There were hundreds of Matamatas and most of them were still alive. Thirty had died, including the little one from the second nest. Lasso took tissue samples from that one, and the other dead bodies, and gave them to Caballero for analysis. According to the police, the turtles came from Villavicencio, but Lasso was not convinced by the story. Why bring hundreds of turtles from the Orinoco if you could get them there?

In his laboratory at the University of the Andes, Caballero and Laura Amaya, one of his graduate students, examined segments of mitochondrial DNA from Matamata from both basins. This kind of circular genetic material contains far fewer nucleotide base pairs than the DNA in the nucleus, which does not make it as informative —it is like the difference between a couple of pages and a whole book— it has the advantage of being cheaper and easier to analyze. Despite their small size, Caballero and Amaya found that there were marked differences between the two kinds of turtles, suggesting that they were indeed two species. To prove it, they would have to check the entire genome and look for samples from all over the continent, but at least they had a good starting point. In the meantime, they contrasted the genetic material of the Matamata from the second nest with that of others from the Amazon basin. The turtle was from the Orinoco, Caballero told Lasso.

The finding confirmed the biologist’s suspicions. “It was a light bulb moment for me,” he told me. The traffickers were “laundering” turtles. The first links in the trafficking chain in the Orinoquía natural region would plunder the nests at exactly the right time – “They are more scientific than we are,” says Lasso – and wait for them to hatch or finish incubating them in special locations and then send the newborn turtles to Bogotá, Leticia and, finally, to the hatcheries in Peru. It was either a way to increase their inventory to meet growing demand or, as the Colombian Attorney General’s Office believes, a way to offer greater variety to their clientele. (Some turtle hobbyist forums on the internet seem to support this idea: at least since 2004, there have been discussions about the possibility of acquiring the “Orinoco shape” of the Matamata).

Caballero and Amaya’s discovery brought an additional complication. Despite the lack of data, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) had classified the Matamata as a species of “least concern” —in other words, as an abundant species with no major threat to its survival —largely because of the wide distribution of its populations. But, if in fact it was not one, but two species, then it was necessary to reconsider that conclusion. That is, the population of the Amazon Matamata may have been fine, but the same may not be true for the Orinoco, or vice versa. Further research was needed to understand the conservation status of the turtle, especially now that it was known that they were being trafficked.

As these studies progressed, the “laundering” of the turtles increased at an accelerated rate. In Colombia, between 2015 and 2022, more than 7,500 Matamatas were seized, according to data gathered by the NGO Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS). That usually means that thousands more reached their destination undetected by the authorities. Exports in Peru seem to support that conclusion: they went from 2,514 in 2015, to 18,355 in 2018, according to the same WCS report, and totaled more than 70,200 individual turtles between 2014 and 2023, according to a recent investigation by the media outlet OjoPúblico on the turtle trade in Peru.

The question of numbers is complex. Monica Morales mentioned that the seizure in which the turtle from nest two was found in 2015 did not appear in official records. I asked Corpoamazonia for all seizure data and copies of the indictments against the persons involved in Matamata trafficking through a freedom of information request, and the seizure mentioned by Morales does not appear. Figures from the Directorate of Carabineers and Rural Security of the National Police indicate that only two Matamatas tortoises were seized between 2023 and June 2024. So far, the Attorney General’s Office has not provided any data or figures.

Trafficking in Colombia proliferated because environmental crimes are not taken seriously, although that is changing, according to several members of different police forces. The Police Environmental Crimes Investigative Unit, for example, went from having five investigators in 2019 to nearly 100 in 2024. The Directorate of Criminal Investigation and Interpol of the National Police (Dijín), meanwhile, opened the first non-human forensic laboratory in Latin America to deal with cases such as that of the Matamatas. Each year, the laboratory participates in more than 20 identification processes, in cases involving shark fin trafficking, sale of harpy eagle claws and illegal exports of other animal parts sold to gullible or ignorant people as fake aphrodisiacs or cures for diseases.

In 2020, Caballero, Lasso, Morales, Amaya and other researchers from Colombia, Brazil, England and Germany were able to demonstrate that there are two species of Matamatas: Chelus fimbriata, which inhabits the Amazon, Esequibo and Mahury River basins in French Guiana, and Chelus orinocensis, which lives in the Orinoco and Rio Negro basins. The discovery and the previous work with mitochondrial DNA, driven in part by the Humboldt Institute and the Omacha Foundation, allowed several of the turtles seized by the authorities since 2015 to be returned to the Orinoco, instead of being released in the Amazon, which would have meant the introduction of a species alien to that ecosystem. Thousands of them were fed one by one with tongs, by patient workers at the Fundación Ikozoa Bioparque del Amazonas, who cared for them —and put up with their bites— until an Air Force plane transported them back to their natural habitat in 2020 and 2021. Others still remain at the Foundation’s facilities.

From 2019 to 2020, Alirio, an employee with the Ikozoa Bioparque Amazonas Foundation, fed thousands of baby Matamata turtles apprehended at the Leticia airport, one by one. He would patiently bend over the tanks trying to entice them to eat pieces of fish from his tweezers. Credit: Santiago Wills

During the pandemic, Susana Caballero and Diego Cardeñosa, another graduate student at the University of the Andes who is now one of the world’s leading authorities on sharks and genetic identification for trafficking issues, developed a low-cost protocol to quickly discern which species of Matamata a sample corresponds to. The Dijín laboratory now has the genetic markers to do the same and has already responded to requests from agencies such as Corpoamazonia and equivalent environmental authorities in other departments (all the Matamatas they have evaluated belong to the Chelus orinocensis species). Controls have been increased at airports such as Leticia, and WCS and other organizations have carried out training to, for example, improve the use of baggage scanners to find wildlife parts.

By the end of 2022, increased trafficking and recognition of the new species, in part thanks to the dead carcass from the second nest, led Colombia, Brazil, Costa Rica and Peru to request the inclusion of Chelus fimbriata and Chelus orinocensis in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). The species covered by this classification are not necessarily threatened, but it is considered that, unless their trade is regulated, their survival may be endangered. The request was approved in January 2023. This means that, in theory, hatcheries in Peru —and any country in the world that wants to export the turtle— must now comply with strict regulations if they want to continue with the business, which moves tens of millions of dollars, according to OjoPúblico’s investigation.

According to the Directorate of Carabineers and Rural Security of the Colombian Police, between 2023 and 2024, only two Matamatas have been seized. This means that, in the best case scenario, the various initiatives have had an effect or, in the worst, that the traffickers are getting better at camouflaging their shipments. There are various levels of optimism depending on who you ask.

InfogrAPHIC: ARIEL TONGLET/SUMAÚMA

III

It ends with a sound. The Matamata from the third nest hatched during the first half of 2015. It felt the sand of the beach between its claws and probably immediately sought out the water of the river. It learned to suck hard on its own and to remain static, like a rock, waiting for the fish and shrimp that live in the waters of the Orinoco rivers.

Over time, its color changed from crab pink to the dark brown of rotting weeds. Its carapace, composed of the dorsal —the upper part—, the plastron and a bony structure called the bridge, grew several centimeters per year, until it reached the size of the width of a guitar case. Its small, pinhead eyes are brown to yellow in color and have dark, rounded pupils. Underwater, the Matamata refined its inner ears to detect vibrations and low-frequency sounds to be on the lookout for predators we cannot detect. With barbs tucked beneath its chin, it sensed the smells of the approaching fish and prepared to open its huge, perennially grinning mouth and inhale them in one breath. Although it is like a snapping turtle or an alligator, it has very few taste buds and doesn’t care whether it eats a shrimp or a particular species of fish. But it might have a preference. Scientists are uncertain on the subject.

The dangers of trafficking persist, despite all that has been done to stop it. At any moment, a person could come along and pull the turtle out of its riverbed. The Matamata would lift its tail and do a foul-smelling fart, but whoever pulls it out must be used to it.

If the turtle is taken away, there are still many actions to be taken to protect it. The police’s specialized environmental unit does not have any personnel at the country’s air and sea ports. Today, searches of cargo luggage or containers leaving the ports depend on the Anti Narcotics Police, which has no idea and is not interested in the issue of wildlife trafficking, according to sources within the institution.

Any forged CITES document or any document that mentions a turtle will usually be enough to get them to approve the departure of one or more Matamata. And this isn’t reprehensible: they have neither the knowledge nor the training to differentiate a slider from a Matamata or a hawksbill turtle. Specialized police are required at river, land and air ports to be able to assess shipments of wildlife (and timber, which is another concerning environmental issue). More resources are also needed for the Dijín laboratory, for example, and more support for the communities where the Matamata is found (trafficking is usually born out of necessity, not evil intent). “It’s like drugs,” says Carlos Lasso. The market must break somehow.

The Matamata turtle has several tubercles or fleshy protuberances on their necks that look like worms when they are underwater. It uses them to attract prey. Photo: Cyril Ruoso / Biosphoto via AFP

The main thing, however, is more research into the species. We still don’t have the answers to basic questions about the lives of the turtles, which could help us protect them. In fact, we don’t even know the level of threat facing the Matamata. Essentially, trafficking may still be happening, or if it has stopped, it could start up again any time unless long-term strategies are devised.

Today, if nothing bad has happened to it, the Matamata from the third nest is more than 9 years old, so it has reached sexual maturity. If it is a female, she lays between 8 and 28 eggs each year. If it is a male, he will look for a mate. Life goes by fast, every hour the equivalent of a few minutes in which not much happens for us. All animals perceive time differently. Our vision makes it feel slower or faster. One way to measure this is through the critical flicker fusion frequency (CFF), the maximum speed at which we can discern whether a light source is constant or whether it is composed of different beams or flashes. A common fly has a CFF of 250. i.e. it is able to recognize when a light source flashes or flickers 250 times per second. In contrast, a human perceives light as constant when it flickers more than 60 times per second. For the fly, then, things happening around it occur much more slowly than for humans (hence how difficult it can be to swat them: the hands we believe to be moving fast are moving at a snail’s pace through the air). Something similar happens with pigeons, which have a CFF of 77, dogs 80, and macaques 95.

The CFF of a sea turtle, the only kind of turtle for which the experiment has been done, is 15. Unless it varies surprisingly, the figure for the Matamata should be similar. This means that for our turtle born in the third nest, in human terms, time is passing at top speed. Our days are hours to the turtle; our minutes are seconds. What we would perceive in a year would occupy the space of a few months for the Matamata.

Paradoxically —or perhaps not— this means that they live much calmer lives than we do. In the same amount of years as us, they experience less stimuli, as they perceive less visually. We might be unable to distinguish the individual flapping of a dragonfly’s wings, but a turtle cannot even see an insect crossing its field of vision.

This calmness is in accordance with its metabolism. The maximum heart rate of sea turtles is around 40 beats per minute, that of Galapagos sea turtles is between six and eight, and some North American turtles may reduce their heart rate to one beat per minute during their hibernation periods. No one has ever measured a Matamata’s heart rate, but it is likely to be low as well. There appear to be no evolutionary reasons for it to be otherwise.

And so, in some stream in the Colombian Orinoquía, our turtle from the third nest waits underwater among the leaf litter, camouflaged among roots or buried in the mud. It perceives a different world, one that is fast and at the same time slow. When a prey approaches, it springs into action: a dragon defying time.

Matamata turtles have unmistakeable faces: their huge mouths seem to be stuck in a perpetual smile, under a pair of gold eyes and a nose that looks like a mash-up of a snorkel and a pig snout. Photo: Luquet M./HorizonFeatures/Leemage via AFP

This report is part of a special on ‘Turtle abduction: the dark trade of illegal traffic in South America,‘ coordinated by Consejo de Redacción (CdR). This project was made possible thanks to support from Internews’s Earth Journalism Network (EJN).

Report and text: Santiago Wills

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Fact-checker: Douglas Maia

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Portuguese translation: Paulo Migliacci

English translation: Charlie Coombe

Copyediting and finishing: Natália Chagas

Editorial workflow coordination: Viviane Zandonadi

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum