“I’ve reached this point of bringing their words for you to know, to understand our world, the way we are—why our dances, why our healing, why our blessings, why the birds are the way they are, why human beings are like this.”

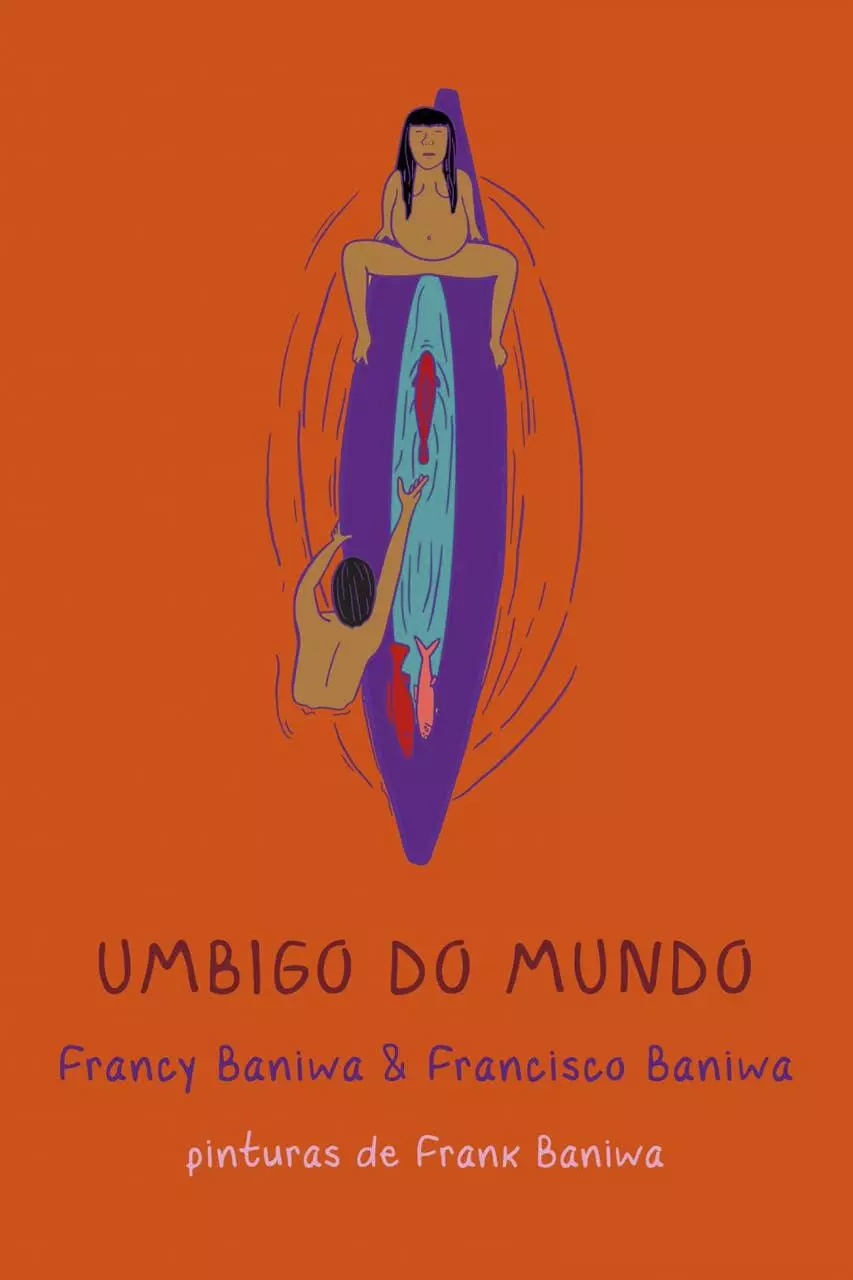

Only someone who is nature itself can make sense of so many why’s. This is how Francy Baniwa, known to her people as Hipamaalhe, launched the first anthropology book written by an Indigenous woman in Brazil: Umbigo do mundo: Mitologia, Ritual e Memória Baniwa Waliperedakeenaai [Navel of the world: Baniwa mythology, ritual, and memory] is also signed by Francy’s father, Matsaape or Francisco Baniwa, and was released by the very unique publishing house Dantes.

No other place could host such a launch. Four and a half years after the fire that destroyed 85% of the National Museum’s collection—an all too literal brutal allegory in a country being brutalized by the rise of the anti-Indigenous far right—the flames have reignited, this time with a new meaning.

The historic building’s courtyard provided the setting for a vigil of ancestral memories that started on the rainy night of April 15 and ended the next morning, a sunny Sunday. All senses were aroused by Indigenous chants and dances held in a circle around a bonfire where two hundred people joined in the happening. The event was organized by the team at Selvagem – Ciclo de Estudos Sobre a Vida [Wild – a cycle of studies about life, or Wild Cycle], a movement focused on Indigenous, scientific, and traditional knowledge, as well as the knowledge of other species. Wild Cycle was conceived by the publisher Anna Dantes, guided by the Indigenous thinker Ailton Krenak, organized by the cultural producer Madeleine Deschamps, and carried out by a group of participants, many of them volunteers.

“We are surrounded by umbrellas, in this unexpected situation where we find ourselves, here around memory,” said Ailton Krenak during the opening ceremony. “This invocation of peoples full of memories is about the expression of ‘body-territory’. It is about the act of establishing memory, of feeling, telling the story of the origin of things, and experiencing these things. A social memory not just of objects but a memory of our effects, of our senses of life.”

Indigenous Baniwa participants (from left to right): Francisco Fontes Baniwa, Francineia Fontes Baniwa, Diego Emilio, Fabricio Ruy Fontes, André Fernando, and Frank Fontes Baniwa. For twelve hours, from dusk to sunset, all the senses were aroused by Indigenous chants and dances, held in a circle around a bonfire with two hundred people in attendance. Indigenous narrators, griôs, quilombolas, academics, figures from the literary world, and storytellers offered guests an immersive experience. Photo: Ana Carolina Fernandes/Sumaúma

Surrounded by relatives, Francy Baniwa explained the relationship of narratives to the reality of the original peoples: “Allow yourselves to travel through these narratives; from there you can understand the importance of these mythologies and the demarcation of territories. And look at Indigenous peoples through different eyes.” The writer explained that her book “begins by telling how the world was once small and has been transforming itself since the creation of the world up through today, where we sit here in this big world.” For the Baniwa people, the universe is made up of multiple layers, associated with various deities, spirits, and other peoples.

Francy Baniwa, Indigenous anthropologist and author of the book Umbigo do Mundo, launched during the ancestral memories vigil at the National Museum in Rio de Janeiro. Photo: Juliana Chalita

Francy is a researcher, anthropologist, and photographer who was born in the community of Assunção do Içana, located in the cultural and ecological area of the upper Negro River, in the state of Amazonas. She has a degree in sociology from the Universidade Federal do Amazonas (UFAM) and a master’s degree in social anthropology from the National Museum of the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), where she is currently doing her PhD. She also knows the river, the fields, and the forest—where she comes from and where she always returns.

The book is a revised, commentated version of her dissertation, in which she transcribes and translates mythical narratives of the Baniwa people, based on her analyses of the accounts of her father, a maadzero [wise man] of her community. Frank Baniwa, the author’s brother, did the seventy-three drawings that accompany the narrative.

Vigil participants took shelter from the rain. When the rain paused, everyone gathered around the bonfire. Photo: Ana Carolina Fernandes/Sumaúma

Umbigo do Mundo has been described by non-Indigenous people as a “literary event,” an “Amazonian epic,” a “cosmological journey through the landscapes of the northwest Amazon,” a “sample of the complexity of the creation narratives of the Baniwa people.” It could only be released as “wild”—as the relaunching of a fire that welcomes memories to fight the fire that destroyed the museum and destroys nature.

After people were welcomed and given some orientation, they milled about the area, equipped with what they needed to get through the night. Banners displaying Indigenous writings and drawings and aesthetic touches like anthills encircled by leaves set a compelling mood for the Wild Cycle.

Firefighter, luthier, and musician Davi Lopes—who fought the fire at the National Museum and afterwards transformed wood from the wreckage into musical instruments—welcomed the guests. Davi’s delicate process of creating the instruments was recorded in the documentary Fênix: o Voo de Davi [Phoenix: Davi’s flight].

Accompanied by his grandson, Fabricio Baniwa, and his son Franky, Francisco Baniwa also gave a brief musical presentation, playing the traditional Japurutu flutes from the Negro River region and dancing with volunteers from the audience. The Japurutu flutes took us to the navel of the world: the Hipana waterfall on the Aiari River, where humanity first emerged and where everything will end, according to Baniwa cosmogony.

Between memories

“To tell a story of the creation of the world—and the world has many stories—our memories must be embodied,” said Ailton Krenak. “We cannot be an empty body. How can we honor this social, plural experience that we make up as a complex society, living among many cultures, many ethnicities, many memories?”

A large part of the collection that went up in flames was the memory of Indigenous people, and on the night the National Museum burned, a number of them rushed there, where they kept repeating: “Our memories, our memories.” Krenak remembered this: “It was a serious loss, but imagine if we had no memory of everything that burned?”

In his remarks on the importance of the book’s publication, André Baniwa, who is currently the director of Territorial Demarcation at the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples, spoke about the process of organizing the Indigenous movement in the Negro River region, including the assemblies that were held and the establishment of the federation of Indigenous organizations and Indigenous schools, which has brought the Baniwa to universities today. “If Brazil and its universities decide to invest in this, the country will have a great potential to create its own identity and strengthen Indigenous cultures. I would still like to see an Indigenous university founded in Brazil, with a type of knowledge more appropriate to and more sustainable for our reality, as demanded by our current situation of climate change,” he stressed.

Indigenous people play Japurutu flutes—a tradition in the Negro River region—for people gathered around a bonfire during the ancestral memories vigil at the National Museum. Photo: Ana Carolina Fernandes/Sumaúma

Idjahure Kadiwel, who is an anthropologist, editor, translator, and Indigenous poet, pointed out that the experience of listening to Indigenous languages where we live should be part of Brazilian education. Idjahure explained that the Baniwa language, which is part of the Aruak linguistic family, is one of about 180 Indigenous languages that exist in Brazil, which is among the most linguistically diverse countries in the world.

Aparecida Vilaça, a professor at the National Museum, UFRJ, and her son, Francisco Vilaça Gaspar, shared the reading of excerpts from one of the stories in Ficções Amazônicas [Amazon fictions]. They wrote the book during the Covid pandemic, drawing from their memories and decades of experience with Indigenous peoples. Francisco concluded his participation by quoting the Argentinean attorney and legal expert Julio César Strassera, who was a prosecutor at the trial of the military officers behind Argentina’s dictatorship (1976-1983): “It is our responsibility to forge peace based not on oblivion but on memory; not on violence but on justice.”

Participants warm themselves near the fire during this moving exchange of ancestral memories, which extended through the night. Photo: Ana Carolina Hernandes/Sumaúma

First warning the audience that she would bring a darker tone to the evening, the poet and artist Amora Pêra read the poem “Mausoléu Nacional” [National mausoleum], written in the wake of the museum fire:

we are all made of the other’s silence

made of erasure

from fifteen hundred to two thousand eighteen

no one saw?

someone laughed a river

while Luzia burned

[name of the oldest human skeleton found in the Americas, stored in the National Museum]

this time she seems not to have survived

[…]

sorceresses sing

saying we can be reborn from ashes

scientists cry and it should make us cry

[…]

memory is an island set afire and erased

our body people burning slowly

our blazing Brazil

our backwardness tragedy discovery

Between languages

After the immersion in Baniwa cosmogony, Indigenous leaders and intellectuals shared with the public their ancestral memories, both their own and those of their peoples from other corners of Brazil. Each and every one of the speeches demonstrated that this experience is only possible when lived and remembered as a collective movement.

The teacher and artist Glicéria Tupinambá explained the process of revitalizing and reviving the Tupinambá mantles, a symbol of memory and resistance. Glicéria looked for mantles in European museums and initiated the process of making new ones with feathers from the birds currently found in her home territory, Serra do Padeiro village, in southern Bahia state. One of the replicas she made was not affected by the fire and is part of the National Museum collection.

Hendu means to listen with the body. The concept was translated by the art curator Sandra Benites, current director of visual arts at Brazil’s National Arts Foundation, FUNARTE. Guarani Ñandeva, from the Porto Lindo Indigenous Territory, in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul, addressed concerns regarding Indigenous people’s efforts to be respected and have their knowledge valued. Sandra described ancestral memories as a worldview, quoting the Indigenous artist Jaider Esbell: “This is an eternity of processes and teaching and learning that has no end. This is truthfully an educational process.”

The word “resilience” echoed in the speech of the female cacique and spiritual leader Catarina Guarani when she explained the process of recovering her community, in Piaçaguera village, in Peruíbe, São Paulo state. She was invited to assume a leadership role during this process and became a cacique; throughout, she remained connected to her spirituality, which is also present in her dreams.

The midwife and educator Cris Takuá, of the Maxakali people, lives in Ribeirão Silveira village in the Ribeirão Silveira Indigenous Territory, in São Sebastião, São Paulo. She described the powers of yerba mate, the healing plant that gives her strength and that dialogues with the female world and sacred beings. The plant has been part of the Guarani people’s rituals and daily life since long before Europeans arrived in America. Later on, some of the Guarani were enslaved to produce the herb.

Introducing himself as a young apprentice on the spiritual path and still learning how to connect with the codes of the wind, birds, and ants, Carlos Papá, an Indigenous leader and filmmaker of the Guarani Mbya people, explained about the importance of sensing one’s own shadow and about the flexibility one gains in the forest by dodging, lifting, and jumping. “A way of dancing all day long.” The filmmaker questioned the never-ending search for happiness in things. He ended his talk by singing the Nhe’ery, “where the spirits bathe,” as the Guarani call the Atlantic Forest.

Between worlds

Ailton Krenak brought everyone back to the bonfire, fascinated by the state of attention generated by the on-again, off-again rain, which enabled the vigil and “the experience of an unpredictable dance.”

“Today we are sharing this pluricultural experience, permeated by individual experiences, weaving a plural consciousness. It’s very interesting to let ourselves open up with a certain abandon and enter into each other’s memories—this gentle invasion of ancestral memories. A much more spirit-enriching experience than that other one they’ve proposed for us, with these devices all over, multiplying themselves, accosting us. It would be very interesting to generate a reaction of the spirit to algorithms. And it is very comforting to think we are capable of taking a creative, regenerating attitude—to recall the expression used by Fabio Scarano [forest engineer, author of the book Regenerantes de Gaia], an attitude that might regenerate Gaia.”

During the Circle of Memories, Ailton Krenak and Baniwa Indigenous people connect with those taking part in the event at the National Museum in Rio de Janeiro. Photos: Ana Carolina Fernandes/Sumaúma

Krenak then invited those taking part to allow their bodies to express themselves in memory, which generated a steady sequence of statements and comments, in a surprising convergence of songs and poems that everyone shared, reliving their own ancestral memories.

The night ended with the narratives of griôs [masters responsible for affective memory and the oral transmission of African culture] and caboclos [people of mixed European and Indigenous ethnicity], realizing the Wild Cycle’s goal of incorporating traditional Afro-Brazilian knowledge. Memories—creative, active, and healing—are also difficult and painful.

Helena Edir Vicente, a community leader and one of the griôs from the Complexo da Maré neighborhood in the city of Rio de Janeiro, began by expressing her gratitude for being there, listening to those stories and reliving her own memories, like the ones she shared with the guests about her grandmother. Helena said that her grandmother was born before Brazil enacted its so-called Law of Free Birth, when “Black girls were sacrificed because only male children were regarded as useful.” The griô pointed out that the only reason her grandmother wasn’t sacrificed was because the owner needed her: someone on the farm had gotten married and wanted a domestic servant. “[My grandmother] was proud of the fact she had been saved; she thought that was lovely. It was only later that I came to understand that her owner only let her live because she needed someone to take care of people who were being born into her family.

In their talks, Helena Edir (seated on the left) and Teresa Onã presented elements of orality from the Yorubá cosmogony to the guests at the vigil. Photo: Ana Carolina Hernandes/Sumaúma

From her grandmother’s memories, Helena went on to tell what it was like to move from the municipality of Conselheiro Lafaiete, in Minas Gerais, to Nova Holanda—the community with the largest percentage of Black people in Complexo da Maré, a district of Greater Rio de Janeiro—and to help form a residents’ association there. “When I arrived in Maré, I found a little of what there had been back in Minas. It was like a small town, with everybody helping each other. There was no water, no electricity, no sewage system, nothing, and we all used to work together to get things done.” Today, Helena is one of the directors of Redes da Maré, an organization that conducts projects in art, culture, memory, and identity, such as a neighborhood arts center called Centro de Artes da Maré, the only local public facility.

Tereza Onã was born Tereza Cristina but adopted the name Onã, which is the designation of an exu [Lord of pathways in the Afro-Brazilian religion Umbanda]. Through the documentary As griots da Maré [The griots of Maré], she has taken these memories to schools and talked about the elements of orality in Yorubá cosmogony with students in Maré, as part of an effort to create an “Afropindoramic” culture—a term that encompasses quilombolas [descendants of enslaved Africans who rebelled], Blacks, and Indigenous and was suggested by the quilombola thinker Nêgo Bispo.

“We are here at a moment of re-signification of the memory of the National Museum. For a long time, we were swallowed by other cultures. I, for example, did not understand this beautiful thing that it is to be a Black woman—this mass of memories, these references,” said Tereza. “Our heroes didn’t die of any overdose; our heroes were murdered.”

Between powers

The day dawned with the drumming of the Senegalese griot and percussionist Pape Babou Seck, who shares the African cultural experience with children in the city of Rio de Janeiro. He explained how a drum is made and invoked his ancestors.

The sun rose with guests taking part in dances, after a night using orality to express their memories. Photo: Ana Carolina Fernandes/Sumaúma

Verônica Pinheiro, who directs the Selvagem Community’s Children’s Group, addressed the subject of the childhood universe and memory. She was followed by the pedagogue and writer Luiz Rufino, whose books include Vence-demanda: Educação e Descolonização [Justicia gendarussa: Education and Decolonization]. Rufino recalled his family’s homeland, the cowhands of Ceará state, and Northeastern Brazil’s arid sertão. As a child, during a bull hunt once, everyone was on horseback, and he fell behind. An old blind man with a staff was accompanying him, and the man asked: “But where’s this bull? Can’t you see the bull? The bull’s in the woods.” But Rufino didn’t see the woods; all he saw was the sertão

Scenes from the dawn: the day breaks with guests dancing barefoot in the wet earth after a night of rain. Photo: Ana Carolina Fernandes/Sumaúma

The sun rose to the sound of Rodrigo Maré, Curcuma Groove, and the flutist Ana Paula Cruz, along with dancing and laziness. A prayer and words from Cris Takuá concluded the ancestral vigil. “Every day the sun rises to warm us, to allow us to go on living. As long as praying men and women continue to chant their good and beautiful sacred words, with the children chanting and enchanting this land, it will still be possible for us to follow the path of living well. I am grateful to each of you who rose with us, who shared your songs, your silences, your concentration. It was a night of many deep movements. I am grateful to each and every one of you who had the strength to spend this long time together. May we continue creating and recreating living possibilities of knowledge transmission, because memories never die, they only fall asleep.”

Participants relax and greet the day after their intense experience in the exchange of ancestral memories. Photo: Ana Carolina Fernandes/Sumaúma

All of the ordinary and extraordinary memories of that night, which will never end, can be viewed at YouTube do ciclo Selvagem, accompanied by Francy Baniwa’s unsettling question, “How does memory permeate our daily lives when life is urban?”

Spell check (Portuguese): Elvira Gago

Translation into Spanish: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Mark Murray. Edition: Diane Whitty

Photography editing: Marcelo Aguilar, Mariana Greif and Pablo Albarenga

Page setup: Érica Saboya