The cacique Kullung-Teie Xokleng, of the Xokleng people in the State of Santa Catarina, in the south of Brazil, appeared stunned when she came up to SUMAÚMA’s team, in the Communications Tent, set up at the Free Land Camp (ATL) 2023 for journalists. She was distressed, rushed and looking for help to communicate with a representative of the Public Prosecutor’s Office. “My people are dying.” The Xokleng people have faced situations of extreme violence in the state during the process of trying to secure part of their territory. Throughout a week at the Free Land Camp (ATL), whichever way you looked at things, all you could see was urgency. All of the indigenous people are in a hurry, because they fear “the sky falling”, which denotes a threat to the survival of all species.

“In the forest we may all die. But white people should not think that we will die alone. They will not live for very long after us,” prophesied the Yanomami shaman Davi Kopenawa in his book The Falling Sky, written in partnership with the anthropologist Bruce Albert. In this logic, if the falling of the sky denotes the end of the world, then salvation necessitates holding up the sky, which means preventing the forest’s devastation. It was for this reason that the 19th edition of the Free Land Camp decreed a climate emergency and demanded effective public policies for preserving nature “from all of the State’s authorities”.

The torrential rain that fell in Brasilia during the evening of the last Thursday in April, after a number of dry hot days, also led to a state of emergency being declared in the camp. Perhaps it was just one of those extreme scenes of climate change that society insists on treating as something that is normal. Crammed into tents and under plastic tarpaulins, in a place that is ironically referred to as Citizens’ Plaza, in conditions verging on the unsanitary, indigenous people lost food, mattresses, blankets and the little other belongings that they needed to remain at the camp until Friday. This was their most important annual gathering, at which representatives of the 305 peoples are called to discuss the directions of their struggle. For almost two decades the indigenous peoples have stuck to the same ritual: setting up camp in Brasilia to overcome the invisibility of their struggle.

Sonia Guajajara, Célia Xakriabá, Ricardo Weibe Tapeba, Joenia Wapichana and the cacique Raoni during the launch of the Mixed Parliamentary Front for the Defense of Indigenous Peoples’ Rights, in Congress. Photo: Matheus Alves/Sumaúma

But the struggle to hold up the sky and prevent it from falling entails demarcating the hundreds of indigenous lands, across all biomes, that have not yet been recognized in Brazil. “Without demarcation there is no democracy,” highlighted the slogan of the Free Land Camp (ATL) 2023, which brought together about 6,000 indigenous people, according to the event’s organizers. After almost six years without any demarcation – Michel Temer’s government only demarcated one Indigenous Land, in April 2018, but the ratification was suspended by a court decision, and former president Bolsonaro did not demarcate anything – Lula’s decision to sign ratification decrees for six Indigenous Lands was a source of encouragement. But it also generated frustration. Since the transition government was set up, in late 2022, indigenous leaders knew that 14 demarcation processes were ready, just requiring the president’s signature. And all of them arrived in April 2023 on the desk of the President’s Chief of Staff, Rui Costa.

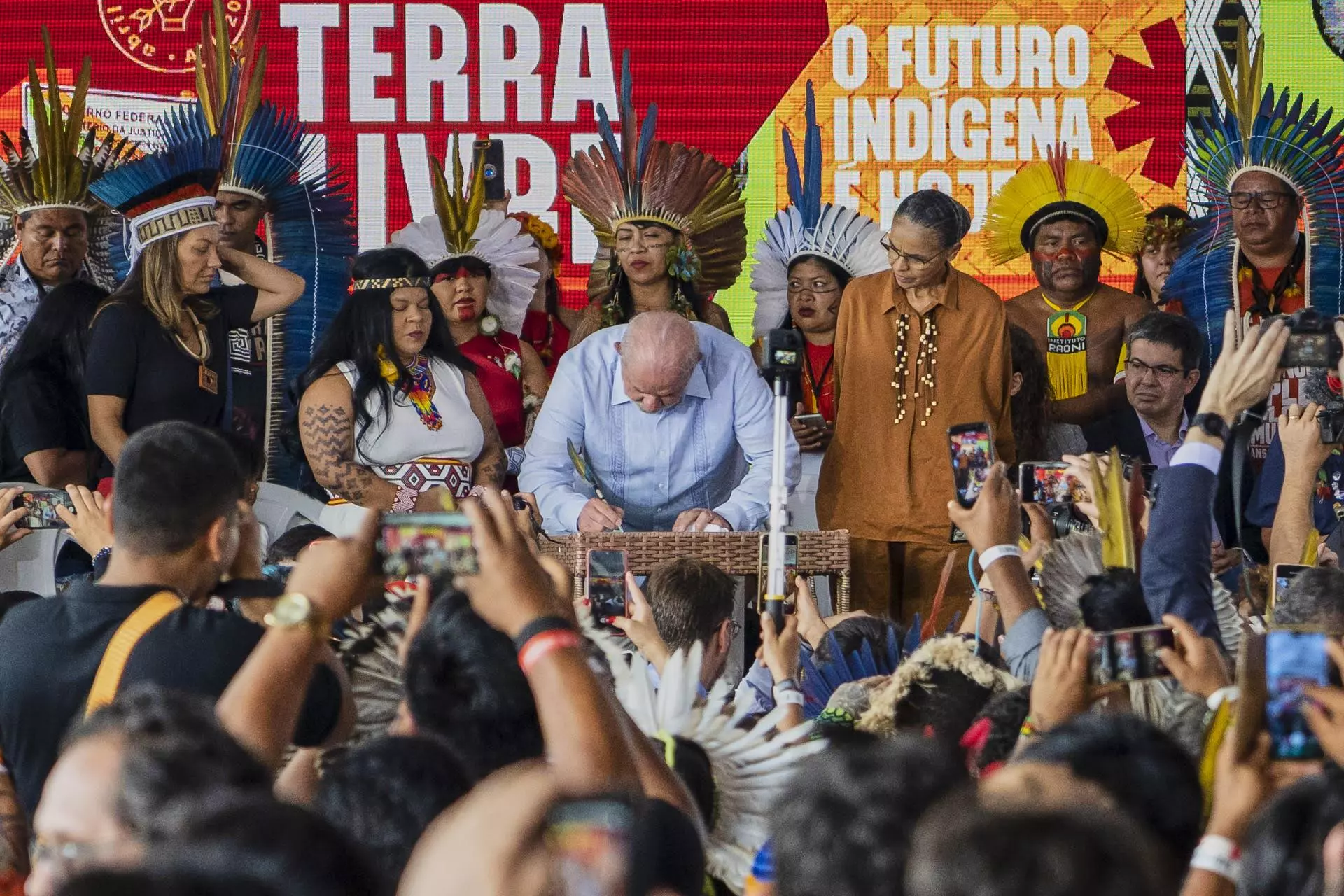

Lula delivered less than expected, but even so it was an emotional moment. The event’s master of ceremonies was the young indigenous activist Samela Sateré Mawé, influencer and communications coordinator of the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (Apib), a SUMAÚMA collaborator. Sam, as she is known among the indigenous people, announced the lands, one by one, while Lula signed the ratification documents: Arara of Rio Amônia (in the State of Acre), Kariri-Xocó (in the State of Alagoas), Uneiuxi (in the State of Amazonas), Tremembé of Barra do Mundaú (in the State of Ceará), Avá-Canoeiro (in the State of Goiás) and Rio dos Índios (in the State of Rio Grande do Sul). When questioned by SUMAÚMA about the political decision to ratify just six Indigenous Lands, the advisors of the President’s Chief of Staff, Rui Costa only replied: “The President of the Republic’s decision was to ratify the six lands announced. We will not comment as to the reasons for not ratifying (any other lands).” Lula brought seven ministers with him to the land ratification ceremony, at the Free Land Camp. Rui Costa was not among them. Lula made some mistakes which did not go unnoticed by the indigenous movement: he got the federal deputy Célia Xakriabá’s name wrong, calling her Caxilabá, and it was also clear that he did not have up-to-date information regarding Brazil’s indigenous population. The president mentioned the existence of eight hundred thousand indigenous people in the country and was corrected by Joenia Wapichana. In the 2010 Census, the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics had recorded a population of 896,917 indigenous people. The president of the National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples (Funai), informed Lula that indigenous people now number 1.7 million throughout the country. “So, you see, Brazil’s indigenous population has doubled. That means you will need more land, more health care, and more schools,” said Lula.

Behind the scenes, government sources explained to SUMAÚMA that the government refrained from ratifying processes that relate to lands that are under dispute in the courts. This is the case of the Morro dos Cavalos Indigenous Land, in the municipality of Palhoça, on the coast of the State of Santa Catarina. The area of roughly 494 acres (2,000 hectares) close to the BR-101 highway and the beaches of the city of Florianópolis is the territory of 600 Guarani M’bya and Guarani Ñandeva indigenous people. In 2008, the Ministry of Justice declared the area to be one of traditional indigenous occupation. This is one of the most consistent and best documented cases for demarcation. But one of the region’s residents is still fighting in the courts for possession of the land.

At the second rally organized by the indigenous peoples who were present at the 19th edition of the Free Land Camp, in Brasilia, leaders were already demanding that President Lula demarcate lands. On the last day, when the president made an appearance, a mere six indigenous lands were ratified. The Morro dos Cavalos Indigenous Land, in the State of Santa Catarina, was not among them. Photo: Matheus Alves/Sumaúma

Demarcating Morro dos Cavalos would be a landmark decision. When she learned this Indigenous Land would not be included in the list of lands to be ratified by Lula, Eunice Kerexu cried. She was at the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples, where, at the invitation of Minister Sonia Guajajara, she is Secretary of Environmental and Indigenous Territorial Law. Kerexu was the first female cacique of her people and is recognized as a leader of the Guarani Mbya people, in the Morro dos Cavalos Indigenous Land. SUMAÚMA caught her comrades in arms questioning her at the Free Land Camp (ATL): “Do you know what saddened me the most? There are 40 declaratory decrees, which just had to be signed. You have to create them. Then afterwards we go forwards to the fight for demarcation. But you have to create the lands. I am very sad,” confided Neidinha Suruí, from the State of Rondônia. Kerexu explained that a number of administrative proceedings have to be followed. And she guaranteed the declaratory decrees, which are initially screened by the National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples (Funai), have not yet reached the ministry. In a demarcation process that is very time-consuming and full of red tape, the declaratory decree is the formal objective recognition phase of the original indigenous people’s rights over a certain area of Brazilian territory. Before the decree is issued, anthropological, cartographic, land and ethno-historical studies are carried out to support the demarcation request process. Ratification is the final phase.

“I know you want answers yesterday. But we need to organize the National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples (Funai),” explained Joenia Wapichana, the entity’s first indigenous president. Joenia stressed, in a full session of the Free Land Camp that the positions now held by indigenous people are strategic spaces they never had before. “And that also presents us with a challenge, namely to reverse the last seven years in which our rights have been trampled on and dismantled and during which there has been a lack of investment and we have been persecuted and have come under a lot of attacks,” said Funai’s president. In Joenia’s own words, the Free Land Camp’s mission is to establish an “agenda that is always provocative to the Executive Branch, the Legislative Branch and the Judicial Branch.”

There was already a feeling of indignation at the Free Land Camp two days before Lula showed up and signed less than half of the expected demarcations. With indigenous people in positions of power, there was no way that information of this type wasn’t going to leak out. And, in the view of many leaders, it was necessary to make room for the collective frustration and avoid any public embarrassment to Lula.

Sonia Guajajara’s speech was carefully calibrated to suggest the indigenous movement would continue to believe in the Lula government, but also to maintain pressure on Lula. The minister made it clear that being a part of the current government is a source of joy and hope for her. But she views the demarcation measures signed by Lula as only “the start of the process of this recovery” of indigenous rights. “The creation of the ministry is merely the first step. We need to move forward,” she emphasized. Three days before Lula’s participation in the Free Land Camp, the minister had warned her “parentes” (or relatives, as this generation of indigenous people refer to one another): “Don’t expect us to resolve 523 years in four.” The president, who spoke to indigenous people at the Free Land Camp, promised to demarcate all the lands by 2026. But this unrealistic pledge was seen as a political ruse to minimize discomfort.

President Lula signs the ratification of six new Indigenous Lands in Brazil, beside the ministers Sonia Guajajara (Indigenous Peoples) and Marina Silva (Environment and Climate Change). Photo: Fernando Martinho/Sumaúma

Lula signed three presidential decrees at the Free Land Camp, which helped to minimize frustration at the lack of demarcations. One of them establishes the National Indigenous Policy Council (CNPI), at the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples, to draw up and monitor the implementation of public policies directed at indigenous peoples. The Working Group for the Mitigation and Reparation of the Effects of Drug Trafficking on Indigenous Populations, under the coordination of the Ministry of Justice was also created by decree. Lastly, Lula signed a presidential decree that set up the Interministerial Committee for the Coordination, Planning and Monitoring of Actions for the Disintrusion of Indigenous Lands – aimed at coordinating the removal of invaders from the territories.

The president did not come under attack. On the contrary: he received applause from the indigenous audience. The picture of the “parentes” or relatives in official government positions is holding the peoples’ anger in check. Memories are also fresh of the iconic presence of the Kayapó cacique Raoni Metuktire. Raoni walking up the ramp of the Presidential Palace next to Lula, at the president’s inauguration ceremony. “President Lula told me that it was time for indigenous people to take charge of these entities [the National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples, the Special Office of Indigenous Health, and the ministry of indigenous peoples], and I agree. Now I want to ask President Lula to strengthen these organizations with financial resources so that you can do your work,” Raoni stated to the leaders of those institutions. The federal government announced the establishment of a career plan for the National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples’ staff. Regarding the budget, the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples’ (MPI’s) operational difficulties have not yet been resolved.

Cacique Raoni hands a headdress with the word “Lula” written on it to the president during the closing ceremony of the 19th edition of the Free Land Camp. Photo: Matheus Alves/Sumaúma

But anger flared up at other times. A Pataxó indigenous man shouted at Minister Sonia Guajajara, just minutes after Lula had left the Free Land Camp. “People are dying! Please, it’s urgent! My people need an answer!” he shouted, while the minister, surrounded by journalists, gave a quick and improvised press conference and her team tried to get round the embarrassing situation.

The Pataxó people, who live in the south of the State of Bahia, yearn for the demarcation of the Comexatiba and Aldeia Velha Indigenous Lands. The demarcation process of Aldeia Velha has been dragging on since 1998. The demarcation of Comexatiba is still in the phase of identifying the indigenous people’s traditional territory, and the process has not moved forward at all since 2015. Meanwhile, the Pataxó suffer from the violence of the region’s farmers – last September an indigenous teenager was murdered by gunmen.

The little indigenous girl Kaywa Pataxó Hã-hã-hãe during the second rally and demonstration with the theme “Indigenous Peoples Declare a Climate Emergency”. The rally was held on the third day of the Free Land Camp, which lasted the whole week, in Brasilia. Photo: Matheus Alves/Sumaúma

That afternoon, in an exclusive interview with SUMAÚMA, Kleber Karipuna, executive coordinator of the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples (Apib), responsible for organizing the Free Land Camp, summed up the situation as follows: “We are in fact having dialogue, hope [with Lula’s government]. I usually say the second semester of this year and the first semester of next year [2024] are going to be vital for us to be able to achieve minimal results, that begin to outline a long-term picture. In a document released at the end of the event, entitled “Letter of the Free Land Camp to President Lula,” Apib was more incisive in its demands of the Workers’ Party government: “The resumption of the policy of demarcation and protection of indigenous lands, with an [implementation] schedule, is essential.”

Along with preparing a timetable for demarcations, Lula’s government has one month to show what stance it will take in relation to another matter that is crucial to the indigenous peoples: namely the judgment of Time Limitations (of demarcation claims) by the Federal Supreme Court, which is scheduled to be resumed on June 7. Under Bolsonaro, the Attorney General’s Office, the body responsible for legally defending the Brazilian State, said only those lands occupied by indigenous peoples when the Constitution was enacted in October 1988, can be demarcated. This stance does not take into account the fact that many indigenous peoples were expelled from their lands before or during the military-business dictatorship (from 1964 to 1985). With Lula in the Presidential Palace, the expectation is that there will be an about-face in the stance of the Attorney General’s Office, as expressed by the National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples’ president. In an important gesture, Lula, at the Free Land Camp, raised a banner of the Xokleng Youth calling for the end of the time limit. But he did not express, in words, the government’s stance regarding this issue.

Way beyond politics…

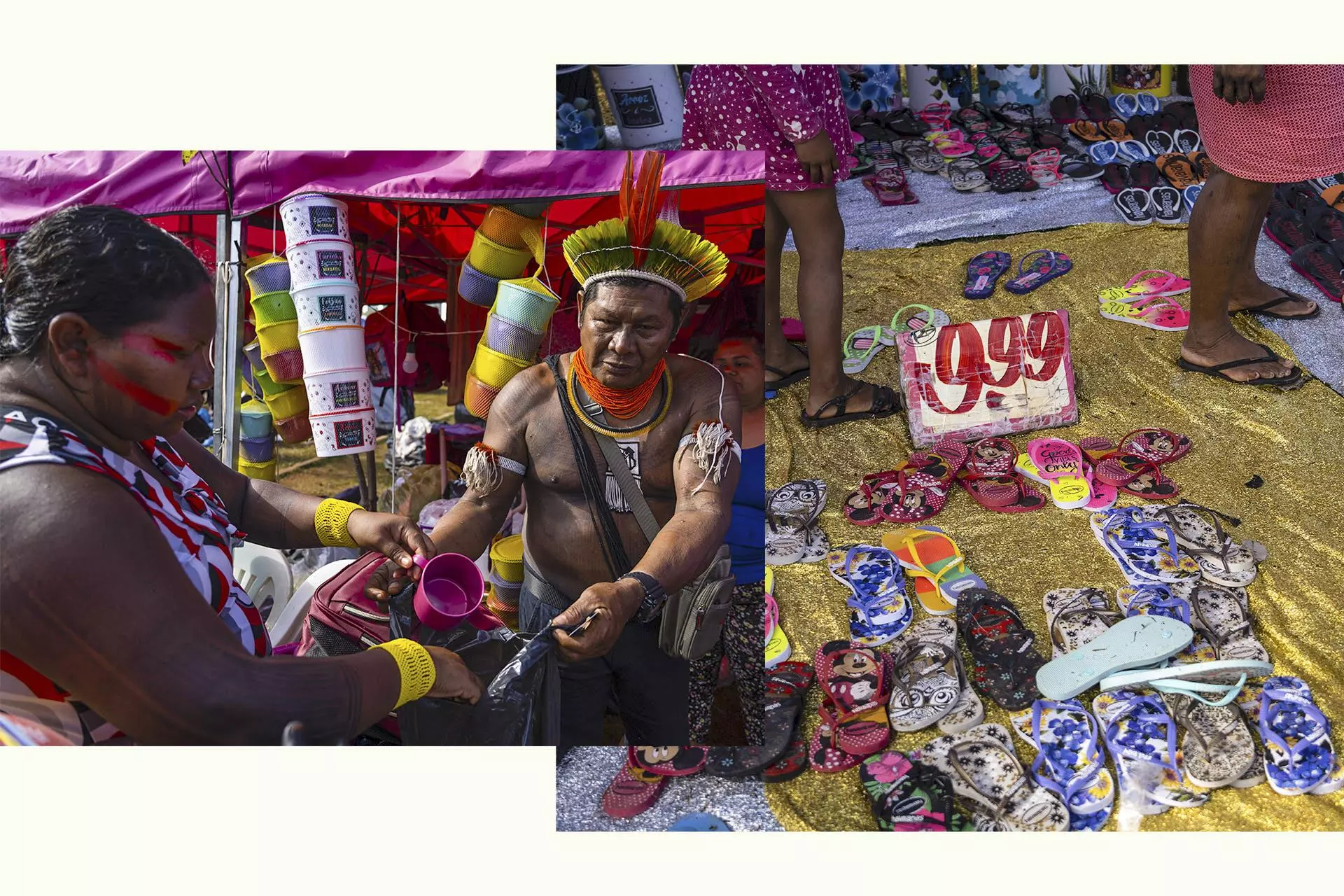

At the commercial tents set up by street vendors in Brasilia, indigenous people bought clothes, shoes, domestic utensils and food at the 2023 edition of the Free Land Camp, in Brasilia. Photo: Fernando Martinho/Sumaúma

The Free Land Camp is a small city that is set up at one end of the Esplanade of Ministries, and this year it was housed in an area near the bus station in Brasilia, in front of the National Theater. According to the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples (Apib), representatives of 180 of the 305 Brazilian native peoples congregated this year. If the first few editions of the Free Land Camp seemed to be out of place in Brasilia, now even the city’s street vendors have realized the event’s potential. Many indigenous people used to ask for help to visit the Paraguay Fair and buy utensils. What we saw this time round, in 2023, was that street vendors have descended on the Free Land Camp offering the indigenous people flip-flops, shorts, gym clothes with graphic designs, summer dresses with straps, functional plastic containers for the kitchens in the camp and in the villages, in which flour, beans and tapioca are stored. If the street peddlers have been able to grasp the indigenous people’s practical needs for these days of the Free Land Camp, it is clear that listening is a good path for the government to follow.

Indigenous rapper group of the Guarani Kaiowá people Bros MC’s giving a performance on the cultural night, on the third day of the 19th edition of the Free Land Camp (ATL). Photo: Matheus Alves/Sumaúma

The Free Land Camp is also establishing itself as a major cultural event. Famous artists, such as DJ Alok – who has 28 million followers on Instagram alone – performed at the camp’s first cultural night. Indigenous youth are everywhere, organized into communication groups, prepared to tell their own stories, with knowledge of all the facts and their own narratives. Audiovisual collectives have emerged, and female leaders, who have been the ones at the forefront of the indigenous movement in recent years, have established themselves. It is the indigenous women who are in the most significant positions representing their peoples in the government. During the full sessions, you heard indigenous men of a new generation praising female personalities and denying the existence of machismo in the villages. But you could also hear many women protesting against violence and asking for specific public policies for indigenous women in the villages. In a debate organized by the Coordination of Indigenous Organizations of the Brazilian Amazon Region, a women’s network left the Free Land Camp with a women’s meeting pre-scheduled for later this semester, to start discussing indigenous female candidates for 2024 and 2026.

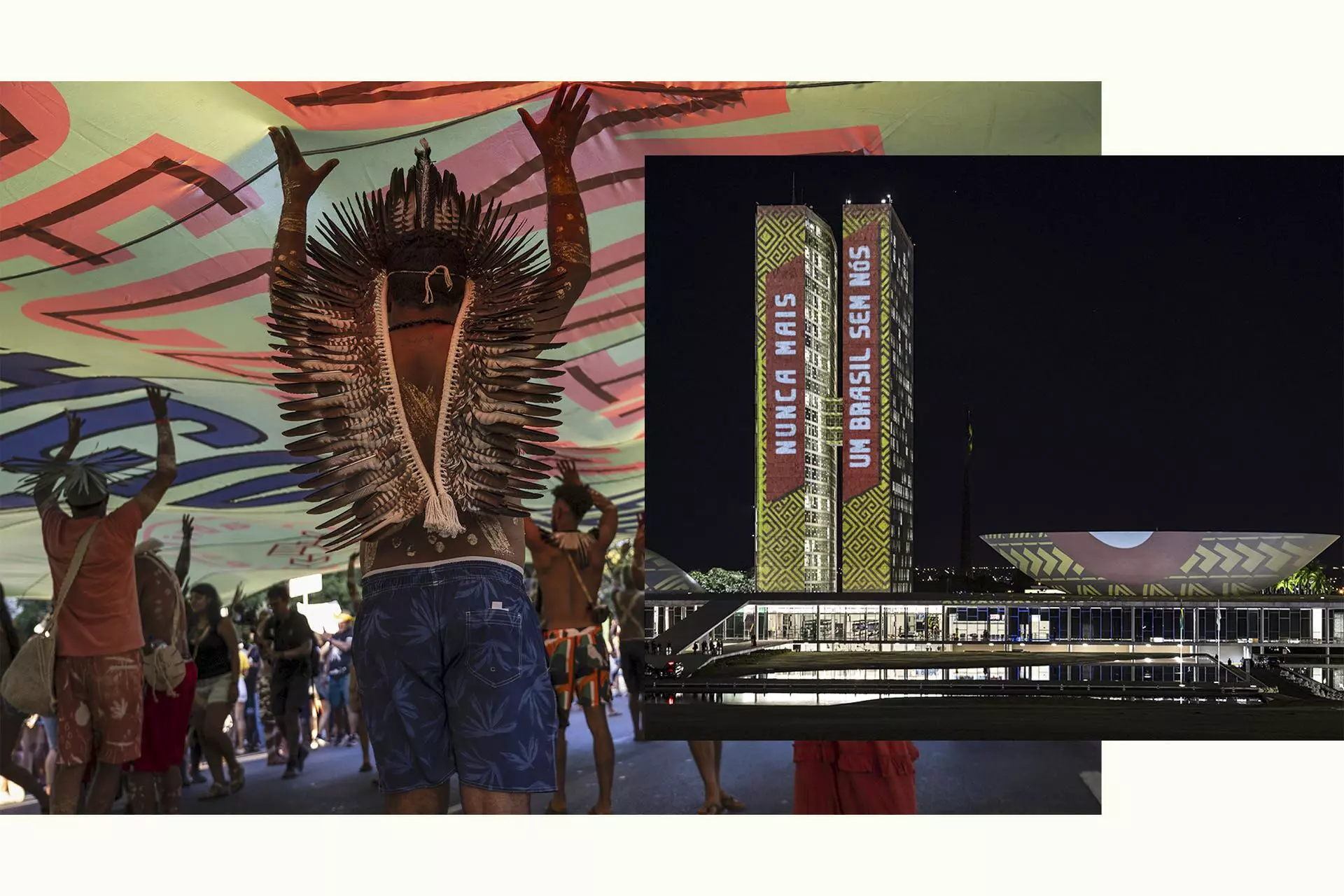

The indigenous rallies that set off from the Free Land Camp are viewed by the indigenous people as true rituals that mix spirituality and struggle. The security protocols imposed as a result of the attempted ‘coup d’état’ on January 8 made it impossible for the indigenous people to gather in front of the Congress and Federal Supreme Court buildings, where they had planned to hold a peaceful act. Even so, Congress was overwhelmed with bright colors and projections of indigenous art and a new vocabulary with the words that the indigenous people want to show to the world: to form villages, to make the world more female friendly, to make women more powerful, to indigenize.

Indigenous people marching along the Esplanade of Ministries, when they decreed a Climate Emergency, and in images projected onto the National Congress at night. Photos: Fernando Martinho/Sumaúma

For the first time, in an organized way, the topic of LGBTQIA+ youth was addressed from the perspective of the right to public policies. Indigenous youth speak openly about the topic, without prejudice. Trans indigenous people circulated in the camp and were respected by their “parentes”, even though there are still difficulties in dealing with the topic among the peoples. The trans activist Symmy Larrat, who is the Ministry of Human Rights’ National Secretary for the Rights of the LGBTQIA+ population, the federal deputy Érica Hilton (of the Socialism and Liberty Party for the State of Sao Paulo), and the drag queen Ruth all turned up at the Free Land Camp for the full session of LGBTQIA+ youth. There was the night of the first Indigenous Ballroom in Brazil, marked by a pronounced presence on the part of young people, who encourage LGBTQIA+ bodies. The ballroom is an act imported from the United States, and consists of an expression of the free manifestation of LGBTQIA+ bodies. It is a movement aimed at recovering self-esteem, of the singularity of expressions, with totally free dances and presentations.

The Drag Queen Ruth Venceremos on the catwalk of Brazil’s First Indigenous BallRoom, at the Free Land Camp, which was also attended by the federal deputy Erika Hilton (of the Socialism and Liberty Party for the State of Sao Paulo). Photo: Matheus Alves/Sumaúma

At the 2023 edition of the Free Land Camp there was a moment of atonement, of strengthening of memory. In the debate about uncontacted peoples, the memory of Bruno Pereira and Dom Phillips, who were murdered in 2022 in the Amazon region of Vale do Javari, was mentioned on repeated occasions. Bruno’s widow, Beatriz Matos, who is the current director in charge of this area at the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples, accompanied the debates. There were also leaders of recently contacted groups, such as the Tapayuna, survivors of genocide in the State of Mato Grosso, the Yanomami, who suffered a genocide under the Bolsonaro administration, the Parakanã, residents of one of Brazil’s most invaded lands, in the State of Pará, affected by Belo Monte. The Parakanã were represented by the leader Menato’a Parakanã, the first woman president of the Tato’a association. One week after the Free Land Camp (ATL), the government announced that the removal of the invaders from the Apyterewa Indigenous Land of the Parakanã should take place before the end of the first half of the year.

There is still a long way to go to “hold up the sky”. But the indigenous movement is gaining new strength under the current government. As Minister Sonia Guajajara said, there can never be a Brazil without the indigenous peoples. “The indigenous future starts today.”

* Letícia Leite, Malu Delgado, Rafael Moro Martins, Matheus Alves, Fernando Martinho, Helena Palmquist

Spell check (Portuguese): Elvira Gago

Translation into Spanish: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Mark Murray

Photography editing: Marcelo Aguilar, Mariana Greif and Pablo Albarenga

The cacique Marcos Xukuru and his people during the Free Land Camp’s second rally, the theme of which was “Indigenous Peoples Declare a Climate Emergency”. Photo: Matheus Alves/Sumaúma