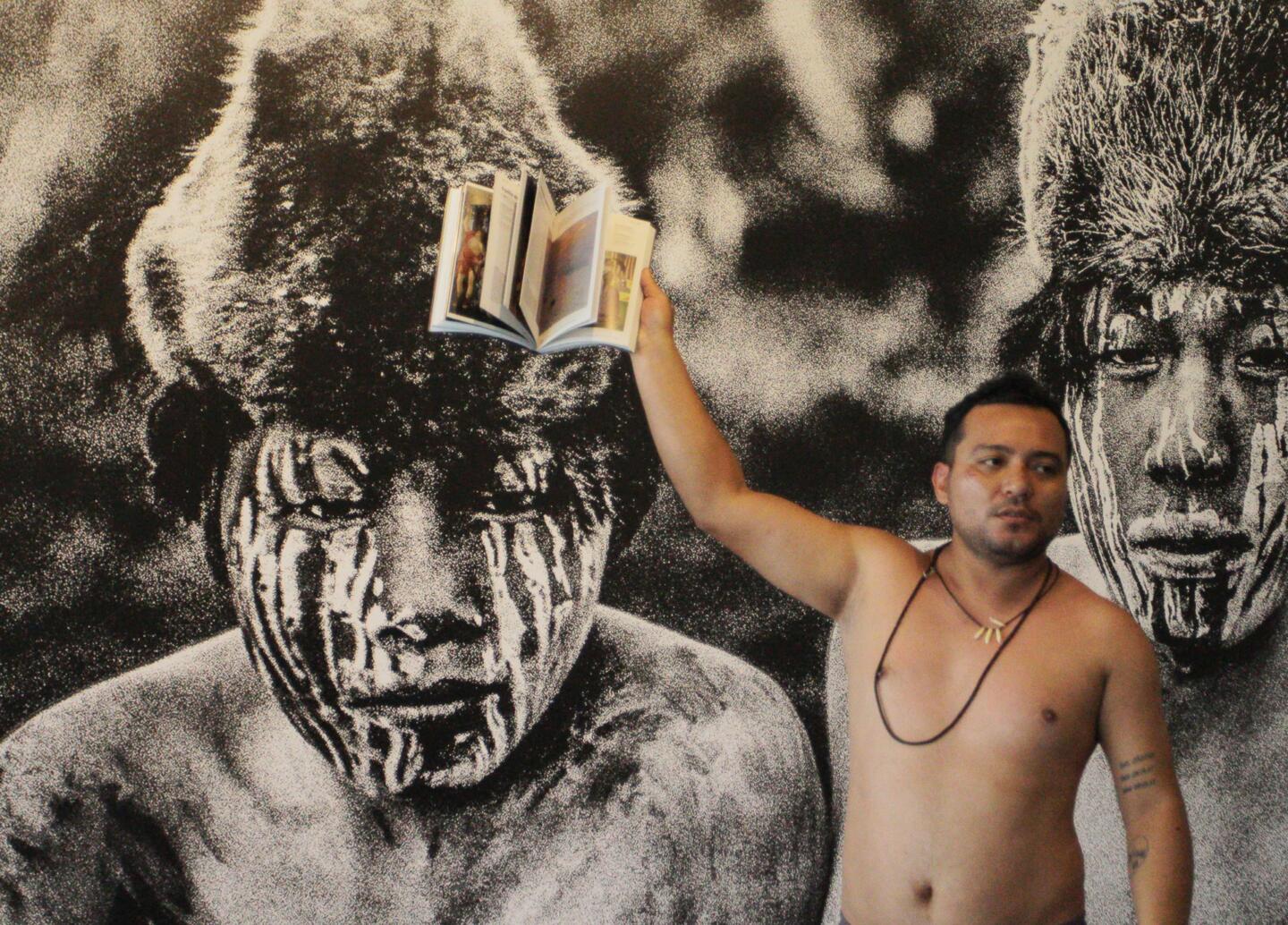

Anyone who attended the 2018 São Paulo Biennial had the good fortune to see Pajé-Onça, a figure who wasn’t on the official program but whose roar made history. Pajé-Onça—Shaman-Jaguar—was the Indigenous artist Denilson Baniwa. Dressed in an animal mask and a cape imitating jaguar skin, holding a handful of flowers, Denilson started out from the Monument of the Bandeiras chanting Baniwa songs; from there, he crossed Ibirapuera Park to reach the show’s main pavilion.

Denilson Baniwa and his performance at the São Paulo Biennial in 2018. Photo: Zedu Moreau/personal archives

“Today I think about how much this action—and others too, by other Indigenous people—has altered the scene since 2018, when ten Indigenous artists might appear some place, until now, when we have 60, 80, very active Indigenous artists appearing all the time. I think it’s amazing,” says Denilson, 39, in an interview with SUMAÚMA. “Brazilian art has long seen Indigenous people and Indigenous production as sub-culture or sub-art.” But performances like Pajé-Onça have shifted the path: “We’re no longer timid, [because we know] there’s nothing ‘sub’ about our production and thinking.”

Denilson’s work will be on display at the Amazon Biennial in Belém, capital of Pará, through November. The show features work by over 100 artists, many from the Amazon—and not just Brazil. Denilson’s art has also been a focal point of the 35th São Paulo Biennial, which opened September 6 and runs through December.

“It’s an opportunity for us to get to know not only this region but the thinking of the region’s artists. It’s important for anyone in Brazil who wants to understand the history of Brazil. Including present-day history,” says Denilson. The artist points out that the Amazon Biennial was curated by a diverse group of women, who embraced dialogue and plurality. “The process involved a lot of conversation among a lot of people. It was lovely to see how the dialogue was trans, multi—and not uni[lateral]. That hasn’t been the case at other biennials I know of.”

Indigenous Peoples Minister Sonia Guajajara looking at the piece Azougue [Mercury], by Denilson Baniwa, on display at the Amazon Biennial in Belém. Photo: Nailana Thiely/personal archives

In this interview, Denilson tells how his artistic journey owes much to Feliciano Lana (1937-2020), a member of the Desana people. “For me, he continues to be the person who enabled me to become an artist.” Denilson also talks about the memoir-biographical documentary he is working on about this Indigenous artist, who died in May 2020. The work of Seu Feliz, as he was known, is on display at foreign museums today, and in any non-racist country would already have been organized and documented. In the Brazil of Denilson Baniwa and Pajé-Onça, erasure will no longer be permitted.

What follows are the highlights of a telephone conversation with the artist in late July 2023. It was a few days before the closing of Escola Panapaná, Denilson’s recent installation at the Pinacoteca de São Paulo. The piece consisted of a three-story-tall structure that hosted language classes, art, music, and other Indigenous cultural expressions.

SUMAÚMA: Why should people in Belém leave home to attend the Amazon Biennial? What does it represent?

DENILSON BANIWA: It isn’t just people in Belém. I think anybody in Brazil should leave home and go to Belém. First, to get to know Belém, right? And then to see a biennial that lies well off the beaten path of Brazilian art. When you think about art, you immediately stick a geographical pin in São Paulo, Rio, Minas Gerais. Holding a biennial in Belém is really significant. There hasn’t been an event of this kind before, bringing people from all the Amazons to one place to talk about art, artistic production, and how this production is implicated in the political and economic process. It’s a diverse group of artists, with very diverse content. It’s an opportunity for us to get to know not only the region but also the thinking of the region’s artists. [The event] is important for anyone who wants to understand the history of Brazil. Including present-day history

What was the road to the Amazon Biennial like?

The process behind the Amazon Biennial was really beautiful and also chaotic, because there were changes in venue, date, curators… What I observed, which wasn’t the case with other biennials I’ve followed, was a process that wasn’t authoritarian or unilateral. It was a process involving a lot of conversation among a lot of people. It was lovely to see how the dialogue was trans, multi—and not uni. That hasn’t been the case at other biennials I know of.

Why not?

In a broader sense, biennials are spaces where social and economic power is disputed. It’s a dispute involving egos because biennials are so important worldwide. The São Paulo Biennial, the Venice Biennial—they present a panorama of artists and artistic production that serves as a new repertoire for everyone, for all the curators, artists, and so on. And this is really fought over. It’s a “democratic” process but at the same time authoritarian. There’s a very fierce dispute over space among curators, supporters, and artists.

Biennials are the pinnacle of any artist’s career. The São Paulo Biennial is the highest a Brazilian artist can go inside their own country. Imagine being at other biennials around the world. The Amazon Biennial took a different route. Of course some things can’t be changed, in part given the structure of art history and the art market. But having only women curators is a milestone at any biennial in the world. And the curatorial team is mixed: Indigenous, Black, brown, white. This is also a really different characteristic: pluri-diversity in terms of ethnicity and place.

Polinização da Memória [Pollinating memory], a sound installation exhibited in 2022. Photo: A Gentil Carioca/personal archives

Which Indigenous artists would you draw attention to at this biennial?

I had the chance to meet Lastenia Shipibo [Lastenia Canayo, a Shipibo-Konibo artist]. She is an amazing person. I’d really like people to get to know her work, her illustrations of plant spirits, the spiritual entity of living beings. This work of hers is truly special. She’s from Peru, an older person of great wisdom. It was amazing to meet her in person. There’s also Carmézia [Emiliano, a Macuxi artist], someone I’ve been following for quite some time and who was recently at Masp [São Paulo Art Museum]. She’s an amazing woman with a remarkable history and a very long career, but no recognition to date. Many Indigenous people have been working as artists for more than 30 or 40 years but have never gained recognition. The fact that Lastenia and Carmézia have achieved this is quite special. I think of artists who are gaining recognition now, like Feliciano Lana, Gabriel Gentil—years after they passed away. I find that so sad… to see such capable artists who enjoyed no recognition while alive.

What work did you prepare for the Amazon Biennial?

They accepted two of my pieces. One reflects on the impact of fish contamination by heavy metal in the Amazon. This is recent research in Brazil; three reports have come out on the contamination of fish by metals like mercury in the Amazon. In other Amazons, such as Guyana, for example, there are already many reports about the impact of this contamination on Indigenous and traditional forest peoples. Brazil is really a long way behind in this research; in fact, they are already discussing changes to laws in other countries. [This piece] is a mural of fishing lures, as a way to talk about fish contamination by heavy metals.

The second project is super different. I’m not that old but I’m old enough to have seen cell phones and the Internet become popular in the Amazon. Before the Internet, our means of communication in the Amazon and the Rio Negro region were rádios-poste [loudspeakers mounted on light poles]. In O Boca de Ferro [Iron mouth], I created an installation that is a rádio-poste that broadcasts Indigenous programs in Indigenous languages and Portuguese. Then I contacted Rede Wayuri [a network of Indigenous communicators in the Rio Negro region, in the state of Amazonas, which partners with our platform on Rádio SUMAÚMA], so we could form a partnership and use audio released in the language during the pandemic. Those are the two pieces. The first, with this environmental concern; the other is more personal, as a communicator, but also about Indigenous and traditional forest communities.

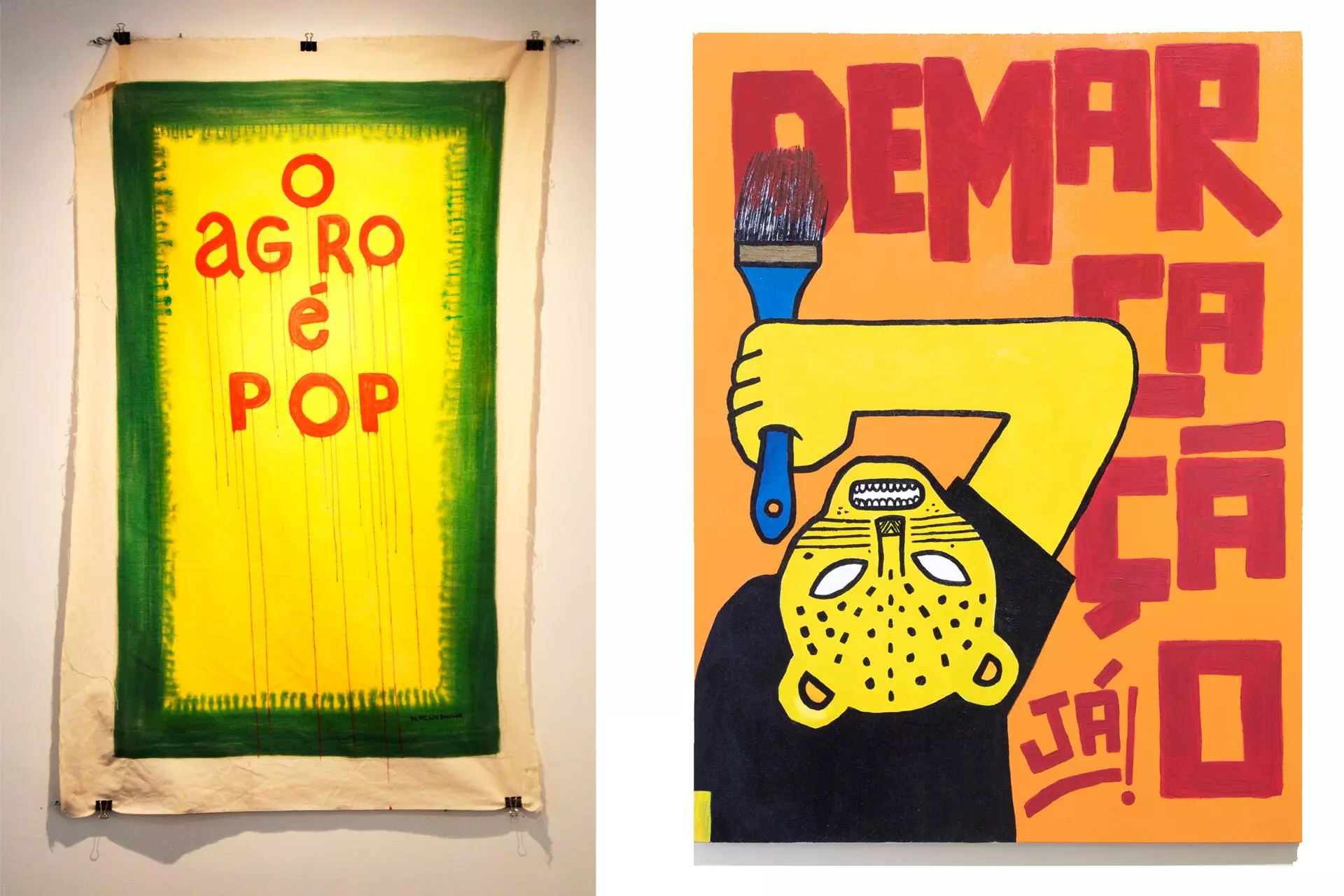

Counterpoint: In his work, Denilson Baniwa criticizes and questions the destruction caused by agrobusiness. Piece on left: Agro is pop. Piece on right: Demarcation now!. Photo: A Gentil Carioca/personal archives

There was a moment in Brazilian art history when the Pajé-Onça [Shaman-Jaguar] went to the São Paulo Biennial [in 2018]. I’d like you to tell us about your artistic interference there.

Brazilian art has long seen Indigenous people and Indigenous production as sub-culture or sub-art, often relegating them to spaces for handicrafts, which is art but not art for a gallery, for a show (unless it’s a show about ethnography). Indigenous people are seen as producing naïf art. Jaider Esbell [an Indigenous artist who passed away in 2021] and I were in São Paulo, looking for spaces we could occupy with Indigenous artistic production. And we kept getting the same answer: “Oh, but Indians don’t do art. Indians do handicrafts and collective art. They don’t have authorship; they don’t have critical thinking.”

We were so upset when we heard those responses that we started attacking rather than dialoguing. When we went to visit the biennial, we saw a number of references to Indigenous culture, but they didn’t say this production was art; instead, it was a theme that the “superior intellectual artist” was working on. That’s when it becomes art. And we were super upset by this. We thought about writing a letter of repudiation, stating: “Don’t you see, you say Indigenous people don’t do art, but you, white people, are living off this sub-product you call Indigenous art.”

Anyway, I don’t remember what came of this, but I ended up with this jaguar mask. And we were talking about people who become animals, who become jaguars, and I remembered this Baniwa story, about the Pajé-Onça. He’s an interdimensional, cosmic being who travels through time, across worlds. I don’t remember where the idea of occupying the biennial came from; it was an unplanned performance. I dressed up as Pajé-Onça and started the performance at the Monument to the Bandeiras, crossing Ibirapuera [Park], through the Modern Art Museum, to then enter the São Paulo Biennial. I walked along singing and playing some Baniwa songs.

Wherever there was some Indigenous presence [in featured works], I would leave a flower, as a mournful tribute. Then in the end, Pajé-Onça tore up an art history book, saying that this art history must be rewritten with the presence of Indigenous people. Given that the Indigenous presence is officialized in art but not recognized, from now on the history of art should truly recognize this presence—not as a theme, not as inspiration, but as a protagonist. For us, this was super radical.

Pajé-Onça’s occupation of the São Paulo Biennial opened new avenues: ‘Our productions changed completely; they’ve matured a great deal.’ Photo: Zedu Moreau/personal archives

Pajé-Onça opened new avenues…

Not just Pajé-Onça but other people. Expressions by Arissana Pataxó in Bahia, Daiara Tukano in Brasília, Jaider [Esbell] in São Paulo and there in Roraima, and Uýra [Sodoma] in Manaus…

How do you think Indigenous art has matured since then?

Since the São Paulo Biennial [2018], we seem to have gained much more momentum, with our productions completely changing, maturing very quickly. Today, for example, I see us in a place of Indigenous art production comparable to Latin America or North America, having sorted out our production and the support we have. What looked like it might stagnate in painting and drawing, today I see how we are doing very diverse things, with videos, performances, sculpture, installations, and conceptual pieces. And also textual production. The artists have evolved remarkably. This is due to the authority derived from self-esteem, from seeing Indigenous artists occupying spaces. We’re no longer timid, and there’s nothing ‘sub’ about our thinking. I’m so happy to see my colleagues’ work in places where even highly acclaimed non-Indigenous artists haven’t even thought of reaching yet.

I’d like you to tell us about your experience at the Pinacoteca, the São Paulo museum that housed your installation Escola Panapaná.

I’m very happy about Escola Panapaná [Panapaná school, a three-story-tall structure exhibited at the São Paulo museum in 2023, with language classes, art, and music taking place inside the installation], with everything it represented in terms of encounters and exchange over those four months. I think it can be replicated by anyone anywhere, in different ways. But I wanted to rest a little. It was intense; it was a PhD. There were 58 activities, more than one thousand enrolled students or attendees. And teachers came from the Baniwa, Tariana, Kaimbé, Sateré-Mawé, Guarani, Xakriabá, Baré, Tupinambá, Fulni-ô, Kariri-Xokó, Pataxó, Tapuya, Terena, Kadiwéu, Mapuche, Wapichana, Bororo, Maxakali, Munduruku, Aymara, Pankararu, and Pira-Tapuya peoples. There were many special moments at Escola Panapaná [a collective noun for a group of butterflies], sharing knowledge so the public could learn more about Indigenous culture and Indigenous identity, the Indigenous presence, Indigenous production, in any area. There was a fashion show, various musical shows, rap, traditional music. Anyway, there were a lot of people and a lot of learning. If a third of those thousands of people [who visited the installation] manage to “panapanar”—to become butterflies that pollinate other minds, other memories—that will make me really happy. I hope Panapaná was a place for nourishing butterflies, for pollination. May they fly off and replicate this knowledge.

From the series Brasiliana – Polinização Invisível [Brasiliana: invisible pollination]: chalk, charcoal, and acrylic on canvas, 2022. Photo: personal archives

Regarding your art involving copies of historical records, historical photos—I think you were the one who inaugurated this in Indigenous art. The exhibits Terra Brasilis: o Agro Não É Pop! and Yurupari 2022 explored the war against agribusiness.

I’m a child of the Amazon Indigenous movement, and this is something that sticks with me all the time, even if I didn’t want it to. I’ve always considered art one of the Indigenous movement’s tools for positioning itself in the world; there are other means—protests, letters… Art has the power to challenge, to be an emotional encounter and create memories that last a long time. O Agro Não É Pop! [Agrobusiness isn’t pop] and these interferences in colonial works are an attempt to create memories from there, to think about our position in the world and about the history of our territory. At school, I always learned the history of Brazil through works of art. When I interfere in these works of art, these historical objects, it’s an attempt to make us think about these works, these records. It’s about creating critical memories from them.

In the case of works like O Agro Não É Pop! I wanted to create a new visual memory. There were some clips on television that said “agro is pop,” “agro is tech,” “agro is whatever.” People in Brazil started to believe in this “pop agro” as the salvation of the Brazilian economy. Meanwhile, they were totally unaware of how agribusiness was destroying the environment and [Indigenous] villages, the violence in rural Brazil, the murder of Indigenous leaders. This work was an effort to counterbalance television advertising, to challenge people with another reality.

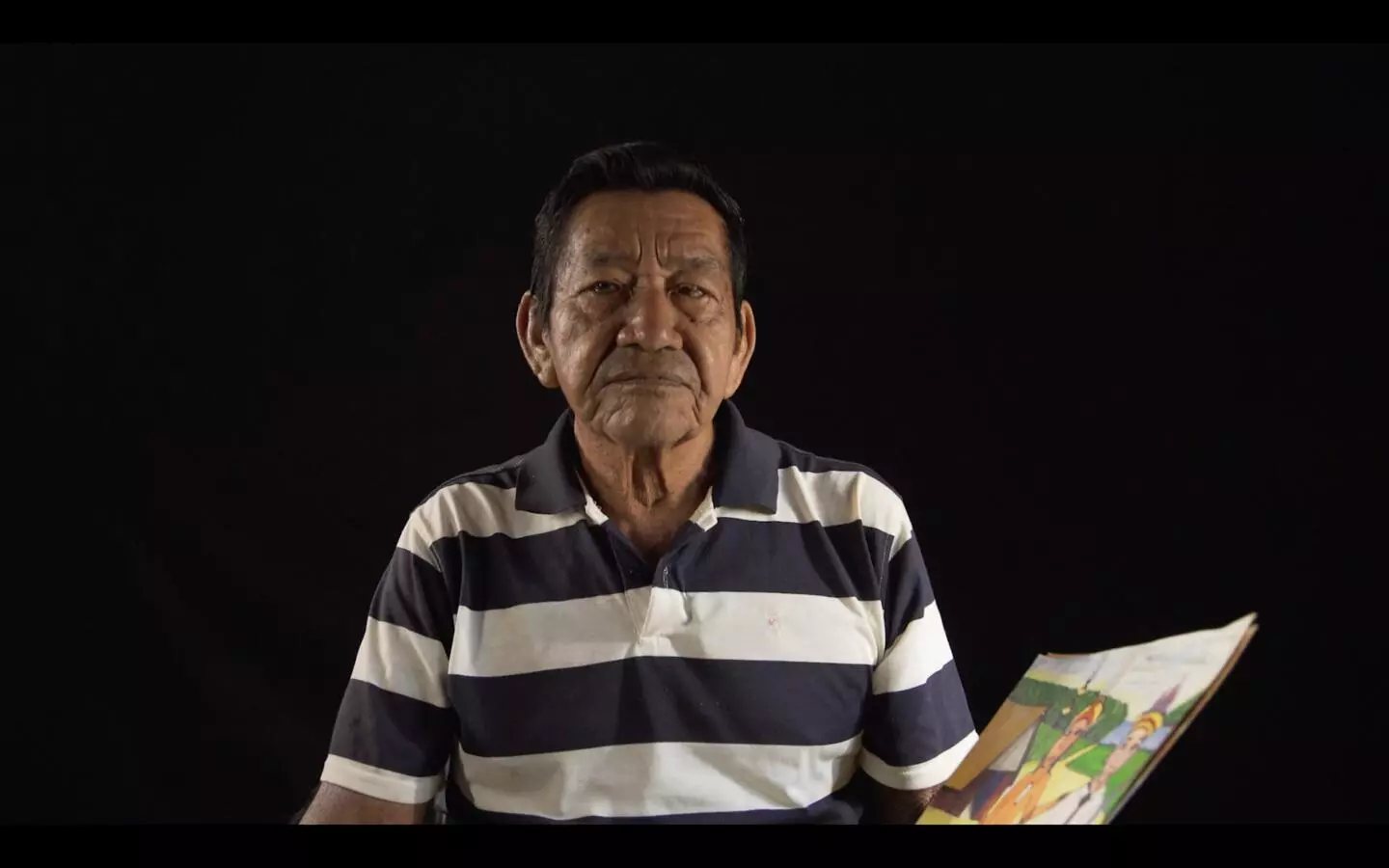

I’d like to close by talking about Feliciano Lana [Indigenous artist who died during the pandemic, in 2020]. I’m sure Feliciano would be at this Amazon Biennial. Why are you, at the height of your career, devoting yourself to documenting Feliciano’s work?

When I was 15, it was the first time I left my community to go to São Gabriel da Cachoeira for an event, a project involving the Federation of Indigenous Organizations of the Rio Negro, the Socioenvironmental Institute, and the Universidade de São Paulo. There were workshops, micro-courses, many things for Indigenous youth. It was the first time I had contact with artistic production I had never imagined. I was in school and reading the classics that everyone reads; I had read some foreign classics translated to Portuguese, some philosophers… and I was learning the history of Greek mythology, Roman mythology. I knew the names of all the gods in the Greek pantheon, for example. And at the same time, I heard a lot of my stories—of my mother’s, my father’s, my aunts and uncles. The stories of the Baniwa, the history of the Rio Negro. When I got to São Gabriel, they had released a collection called Narradores Indígenas do Rio Negro [Indigenous narrators of the Rio Negro]—and the illustrations in the book were by Feliciano Lana. It was the first time I had a visual idea of the Rio Negro Indigenous pantheon.

Feliciano Lana’s illustrations of Rio Negro stories were Denilson Baniwa’s chief artistic inspiration. Photo: Thiago da Costa Oliveira/Ethnological Museum of Berlin

And then I had access to [the book] Antes o Mundo Não Existia [The world didn’t exist before], stories likewise illustrated by Feliciano. It changed my life, definitely. It was the first time I saw the face and form of all of these ancient stories we had heard. When I decided to devote my life to being a real artist, everybody asked me what my inspiration was or what artists I liked. I would talk about Feliciano Lana, Gabriel Gentil… Not long ago, I was thinking a lot about Feliciano and his importance for the birth of many Indigenous artists in the Rio Negro region and state of Amazonas, how much he was a pioneer in creating an aesthetic, in creating historical images, in creating a Rio Negro and Brazilian visual narrative repertoire.

I had a project with my grandmother, drawing from the thinking of Feliciano Lana, [the idea of] making a documentary and interviewing her. I kept putting it off, putting it off, and my grandmother passed away. I met Thiago Oliveira, an anthropologist who studies in Berlin, and we decided to make a documentary about Feliciano Lana. We started interviewing him, and then we asked him to do something he’d never done before. He had always written about the Rio Negro mythological narrative, but he had never illustrated the story of non-Indigenous contact and presence in the Rio Negro region. So we asked: “How come you never drew anything about the priests, the military?” And he said, “Well, nobody ever asked me to.” [laughs] Then we said we’d provide him with the resources to do drawings about this contact. He started doing drawings about the contact with priests, life in Salesian boarding schools, the arrival of the military, big mining companies, and all.

Unfortunately, the pandemic came along in the middle of this process, and he ended up dying of COVID-19. We were very shaken up by this, and we really wanted to finish this project, not as a narrative biographical documentary but as a memoir biographical documentary, of his passage through this world. For me, he continues to be the person who enabled me to become an artist. He allowed me to understand that Baniwa and Tukano history and gods, for example, are as important as the gods Neptune, Aphrodite, and Zeus. And that the Indigenous visual and narrative history of the Rio Negro is as important as any other visual narrative of any other country or civilization.

Spell check (Portuguese): Elvira Gago

Translation into Spanish: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Diane Whitty

Photography editing: Lela Beltrão

Page setup: Érica Saboya

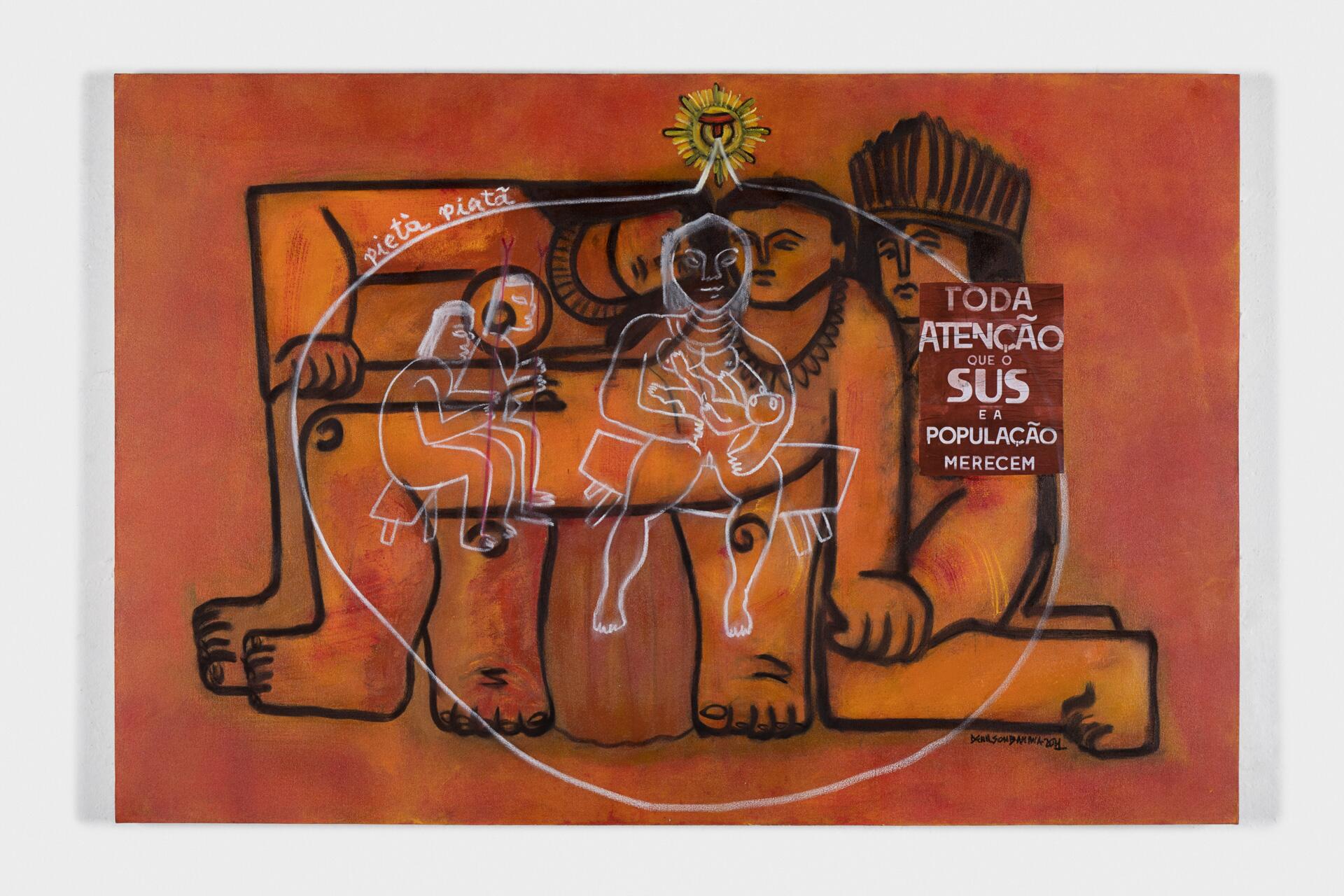

Pietà Piatã: Collage, charcoal, and pigment on canvas (2021-2022). Photo: A Gentil Carioca/personal archives