The wooden house is being slowly dismantled, board by board, shingle by shingle. It will have to be rebuilt far from the river. This forced move is the only solution left for Ana Alice Soares, 25, a resident of the Leonardo Barbosa neighborhood, in the city of Brasiléia, in the Brazilian state of Acre, on the border with Bolivia. Ana Alice is one of the first environmentally displaced persons in one of the municipalities most heavily impacted by extreme weather events in the Amazon. In less than a year, from March 2023 to February 2024, her home was hit by two floods on the Acre River.

“We can’t go on. We just came out of flooding last year, now again. You lose your things, furniture, everything you worked hard to get,” the young lady says. Her house was barely spared from being carried away by the current. Her neighbors were not so lucky.

A city submerged: the streets in Brasiléia’s city center are overtaken by the Acre River’s flooding in February. Photo: Gianfranco S. Aguiar/Brasiléia Municipal Communications Office

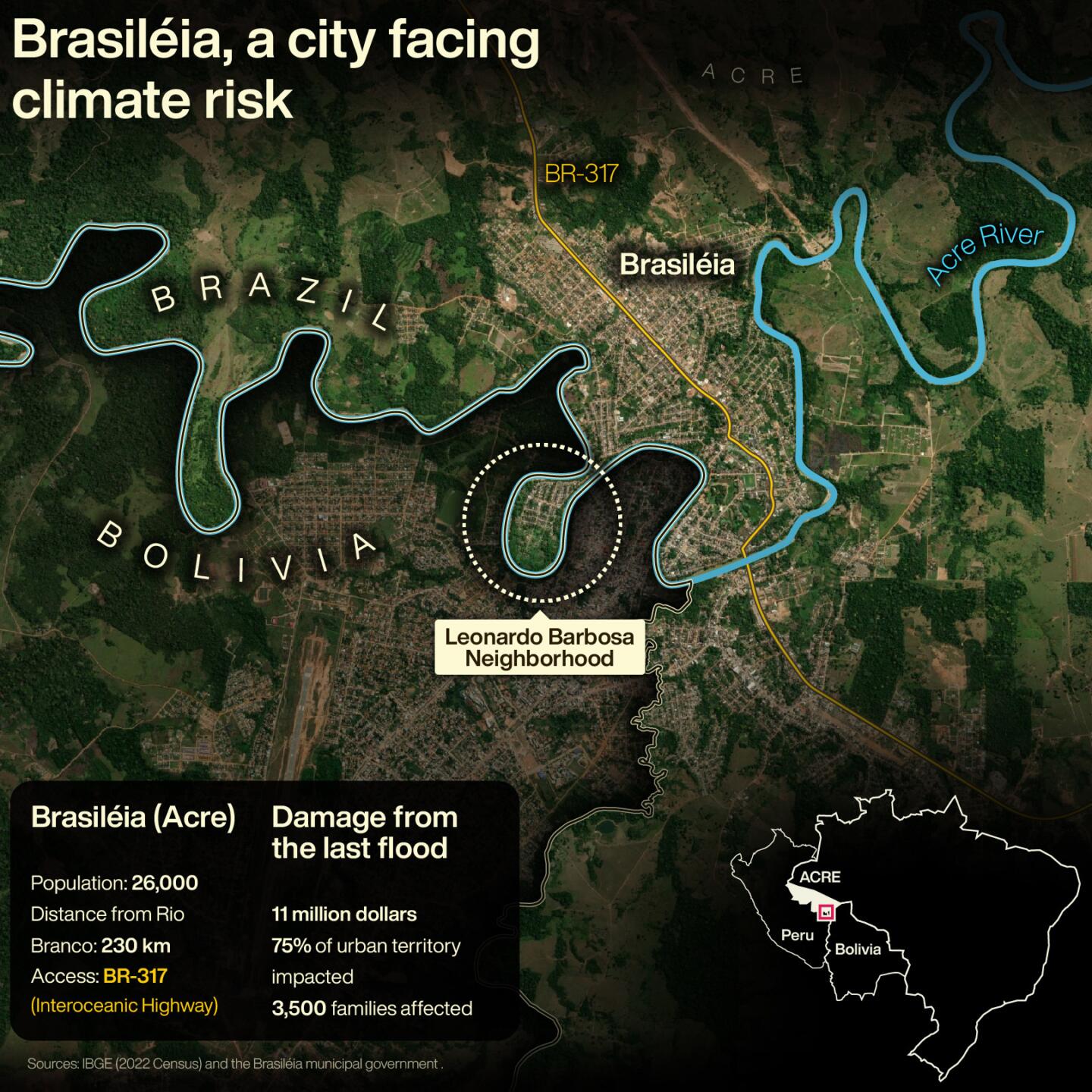

The Leonardo Barbosa neighborhood sits in a peripheral area of Brasiléia on a tight bend in the Acre River, where the waterway forms a U. During flooding, the water rises and covers the open end of the U — turning the neighborhood into an island. Locally they joke that it will be incorporated by Bolivia, the country on the other bank of the river.

This year, as February turned to March, the river’s strength broke through Catraieiros Street, the community’s main thoroughfare, turning the street into an island as well. The municipal government used boats to deliver food supplies and drinking water. Once the waters subsided, emergency construction reconnected the community to the city. The municipal government says that 42 families were left without homes and have nowhere to go.

Ana Alice will rebuild her house in the same neighborhood, on a piece of land next to her mother-in-law Iranira de Melo’s home. Iranira, who used to live on a rubber tree plantation in Bolivia, has endured flooding since she moved to the region. “The first big flood was in 2012. Then, 2014 and 2015. I couldn’t take it and I bought a little piece of land on the high ground, away from the river.”

Ana Alice and Iranira are victims of the social and environmental tragedy caused by extreme climate events in this part of the Amazon. The years alternate between severe flooding and drought, putting lives at risk in urban communities and in communities of traditional Ribeirinho forest peoples, Indigenous peoples, farmers, and extractivists, by destroying farmlands, livestock, and sources of drinking water. According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, a partner of the UN’s International Organization for Migration, there were over 708,000 displacements in Brazil due to socioenvironmental disasters in 2022 alone. Events that turn people like Ana Alice and her mother-in-law into climate refugees.

Forced move: Ana Alice Soares will have to disassemble her home and rebuild it farther from the river

Brasiléia forced to rethink its place

A large part of Brasiléia may have to move. The centuries-old city which sprouted on the banks of the Acre River is not sure how many floods it can still withstand. With each major flood, buildings like the City Hall, the Municipal Chamber, the Courthouse, and state and federal agency buildings are submerged. “It’s not easy moving a 113-year-old city. Beyond the economic issue, there’s the cultural issue. These are people whose entire lives lie along the riverbank: shops, homes,” says the mayor, Fernanda Hassem. She says the damages caused by flooding to Brasiléia’s urban infrastructure run up to U$ 11 million.

Twelve of the municipality’s 15 neighborhoods were affected – 75% of its urban area. A total of 420 families had to move. “The proposal is to build public housing complexes on the high ground, with safe housing. The municipal government doesn’t want to destroy the city’s low ground. It’s part of our history, but we need to provide options for those with nowhere to go,” the mayor says.

Brasiléia’s population began to live with routine major flooding starting in 2012, when the river swelled to 14.55 meters. Only the roofs could be seen on some homes. Only small boats, like catraia boats and fishing boats, could move through the central region. These scenes were repeated in 2023 and 2024. This year, the Acre River reached a highwater mark of 15.58 meters – three centimeters above the 2015 mark, the previous record for the municipality’s highest flood.

InfogrAPHIC: Rodolfo Almeida/SUMAÚMA

When SUMAÚMA arrived in Brasiléia in late March, it had been two weeks since the waters had receded. Water trucks were washing the streets and an odor lingered from the sludge left by the muddy river. Walls and floors bore marks from the water. Even with the river back in the riverbed, the streets continued to crumble, and there were warnings of collapses.

Becoming an island: in the Leonardo Barbosa neighborhood, a part of Catraieiros Street was destroyed by the Acre River, cutting the area off for some time

Brasiléia also bears other marks. Like those left by the criminal factions spread across the region. In what was left of the sports court and the small square in the Leonardo Barbosa neighborhood, the B13 faction’s graffiti tags make clear who runs the territory. In Acre, the group is allied with Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC), a São Paulo-based faction that came to the Amazon to control the route for drugs trafficked from neighboring countries.

Brasiléia’s proximity to the Bolivian city of Cobija, the capital of the Pando department, leaves its population vulnerable to disputes over the international drug market. Young people in low-income areas are the first victims. Those not coopted by drug trafficking put up with a routine of considerable violence, between an absent State, the fear imposed by crime, and the impacts of flooding.

At the margins, a stubborn hope

In a scenario of hardship, there is also resistance and hope. Janaína Souza, 23, lives in the Samaúma neighborhood, on the shores of the Acre River. Her story is like that of many women from the Amazon’s urban peripheries, always at the margins – of the river and of possibilities for social mobility. “It was the cheapest place to buy a little land. We paid a downpayment, then installments. It floods, but it’s ours, we don’t pay rent,” says Janaína. Her husband has severe back pain and is unable to work. The couple’s only income comes from Janaína’s work as a digital influencer.

She posts videos of her day-to-day life in the Samaúma neighborhood to Tik Tok and Instagram, earning her R$ 600 (U$ 115) per month. During the flood, she talked about what living at a shelter was like and showed her home completely covered by water. This is how she is able to live – or survive, as she prefers to define it.

“It’s hard to live where it floods. We’re always afraid of whether the river will flood, because you never know with nature. There was [a flood] last year, and nobody was expecting [one] this year because it used to be every three years, every five years, and now, less than a year and a half later, another flood came,” says Janaína.

Online: Janaína Souza (wearing black) posts stories about the floods; her sister Dalvania’s bathroom was carried away by the water

She plans to save up money from her work on social media and move her family. “I never try to see the bad side of things. I try to see the good side. I am thankful for my life, I’m healthy.” Her videos convey joy, good humor, and serenity.

‘It was as if we didn’t exist’

Past the Leonardo Barbosa neighborhood is the 28 de Maio neighborhood, a Jaminawa community which is the largest urban concentration of Indigenous peoples in the Upper Acre River region and which is also controlled by the B13 criminal faction. Jaminawa youths have been coopted to act as “soldiers” for the factions.

It is estimated that over 80 Jaminawa families reside within the municipality of Brasiléia. Forty of them are in the 28 de Maio neighborhood. The community has potable water and electricity. Streets are unpaved. Many homes’ structures were compromised by the flood, and their walls show the water’s marks.

While SUMAÚMA was talking to a community leader, a “scout” passed by on a motorcycle to see who was there and what they were doing. Safety is only found in the presence of a local leader.

“The biggest challenge we face is prejudice, which has never gone away. We were invisible for many years, people who didn’t exist. I grew up here, we had no help at all. It was as if we didn’t exist,” says the president of the residents’ association, Marilza da Silva Jaminawa, 37.

‘We’re invisible’: Marilza Jaminawa feels official policies forget urban Indigenous people

The Jaminawa are a people in constant movement. They are spread across almost all of Acre, in villages and cities. Within the urban context, they are “unprotected,” outside of the scope of federal policies focused on village-dwelling Indigenous people. In Brasiléia’s peripheral neighborhoods, they are among the groups most vulnerable to flooding.

Rubber-tapper resistance submerged

Brasiléia is one of the cradles of the rubber-tapper resistance to turning rubber tree plantations into pastureland for cows, from the 1970s to the 1980s. The Union of Rural Workers of Brasiléia was one of the first in Acre to organize rubber-tappers to fight against the “paulistas,” as people from São Paulo are known, who were coming to the Amazon with incentives from the business-military dictatorship (1964-1985).

Along with Chico Mendes, Wilson Pinheiro, the president of the union in Brasiléia, was one of the movement’s most important figures. On July 21, 1980, Pinheiro was murdered in an ambush while leaving the organization’s headquarters, the victim of the dispute between the rubber-tappers and the gunmen hired by “Acre’s new owners.” Eight years later, Chico Mendes would be executed in the Xapuri neighborhood.

For four decades, the union’s headquarters operated out of a wooden building in Brasiléia’s center, its white walls dirtied by the mud from the river. With each major flood, the water reaches the roof. In a visit to Brasiléia in March, Environment and Climate Change Minister Marina Silva recalled its history: “I was overcome with emotion when we went by the Union of Rural Workers of Brasiléia, which carries Wilson Pinheiro’s name. He was murdered to protect the forest.”

Over the last 50 years, Brasiléia has been one of the municipalities in Acre most affected by the forward march of deforestation. There are no longer any forests between the over 230 kilometers from the municipality to the state capital of Rio Branco. The entire surrounding area is made up of large grain and cattle farms. The last area of forest, yet one still under pressure from growing agribusiness, is the Chico Mendes Extractive Reserve, the fruit of rubber-tapper resistance.

Resistance: the Chico Mendes house in Xapuri after the flood. Photo: Ronaira Barros

No roof, no floor

The last flood in Brasiléia left homes without roofs. Once the waters retreated, the owners returned to find themselves literally without a roof over their heads. Only the walls are left on the home located in the city center that belongs to Antônio Braga Correia, 56. He is temporarily living at his brother’s house, which was not swept away by the river, and which did have any shingles come loose. “I’m afraid a gust of wind will take everything,” he says.

Antônio was not expecting more high water so soon after the 2023 flood. “We always think the water won’t rise much, but when I looked, it was already above the walls. Nothing could be saved. The mattress was rotten. It was so heavy, I had to pull it out of the house with a rope.”

The fruit orchard in the yard, with açaí and banana trees, was lost. Antônio practically only kept the clothes he was wearing. An electrician, he works on a job-to-job basis and has no fixed income. “Now it’s time to work, wait for the clientele to be able to recover.”

What remains: seen from above, Antônio Correia’s home, its roof taken by the water, is a void surrounded by wreckage

The floods in Brasiléia have had profound impacts on the local economy. The city, which neighbors Bolivia, makes its living from the flow of Brazilians heading to Cobija to shop, go to school, or find more affordable medical treatment. Brazilians and Bolivians share bars and restaurants, and one of the most popular is Renato Gastro Bar, on the Acre River waterfront. It has been open for three years and has already flooded twice, with water rising to the ceiling. Its owner, Renato Oliveira, says the “advantage” of Brasiléia is that people have up to 72 hours to leave, since the floods start at the headwaters, on the border with Peru. “When news reaches us of the river flooding up in Assis Brasil [at the border with Peru and Bolivia], it’s just enough time to get everything out before the water arrives here,” he explains.

Isolated: a resident stranded on top of a roof waits for help in Brasiléia’s water-drenched central area. Photo: Brasiléia Municipal Communications Office

This report is a partnership between Jornal Varadouro, an Acre-based journalism platform, and SUMAÚMA

Report and text: Fabio Pontes

Editing: Fernanda da Escóssia

Photos: Gleilson Miranda

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Spanish translation: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Sarah J. Johnson

Infographics: Rodolfo Almeida

Copyediting and finishing: Natália Chagas

Editorial workflow: Viviane Zandonadi

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum