A sixty-year-old Indigenous man named Baré Bornaldo sits at the microphone. Military personnel in camo field uniforms and jackboots watch him closely. The scene in question takes place in a maloca, or communal hut, in Waimiri Atroari Indigenous Territory, located between the northeastern region of Amazonas, and Roraima, in the Brazilian Amazon. Bornaldo is a witness to a crime committed in his village. One of the very few to survive. The public hearing being held in a Federal Court is part of a lawsuit filed by the Federal Prosecutor’s Office against the Brazilian government. It is February 27, 2019. It is also the first time the Waimiri Atroari people, who are generally reticent, are speaking publicly about events dating to half a century ago, during the business-military dictatorship of 1964 to 1985. “I lost my father, my mother, my sister and my brother,” Bornaldo said. And he was just getting started.

Kinja (pronounced Kinyá) is what Baré Bornaldo’s people call themselves. The term means the “true people.” At least eight Kinja villages were attacked between 1974 and 1975 by a Jungle Infantry Battalion, which used combat aircraft to launch chemical attacks. According to Indigenous testimonies in the expert report to which SUMAÚMA was given exclusive access, the bodies burned on the inside. The document’s author, specialist João Dal Poz Neto, states that the chemical weapons “resulted in deaths among the residents” without affecting the malocas or the forest around the villages.

Public Prosecutor’s Office demands R$ 50 million as compensation for village attacks during dictatorship. In this February 26, 2018 image, Indigenous people welcome a delegation of lawyers. Photo: Raphael Alves

In some cases, after spraying villagers with poison, the Army then deployed ground troops armed with firearms and machetes. The report affirms that after the coordinated attacks, which Neto calls a true “war of occupation,” survivors were forced to flee into the jungle. Villages were decimated. Anything to ensure the Indigenous people got out of the way of BR-174, one of the highways the dictatorship built in order to bring “progress” to the Amazon.

It is estimated that 58 Indigenous people died during those eight attacks. But the National Truth Commission estimates the total number of Kinja people killed between 1972 and 1977 was as high as 2,650—not only during construction of the highway, but also due to subsequent diseases contracted from white people. The National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples estimated that the Kinja population numbered 3,000 at the time. Nearly the entire Kinja population was exterminated.

The Public Prosecutor’s Office declared it a genocide in its public civil suit. This is why they are requesting a compensation of 50 million reais and a public apology from the federal government for the violence perpetrated against Indigenous people between 1974 and 1975 during construction of the highway that currently connects Manaus and Boa Vista. A verdict is expected in the coming months.

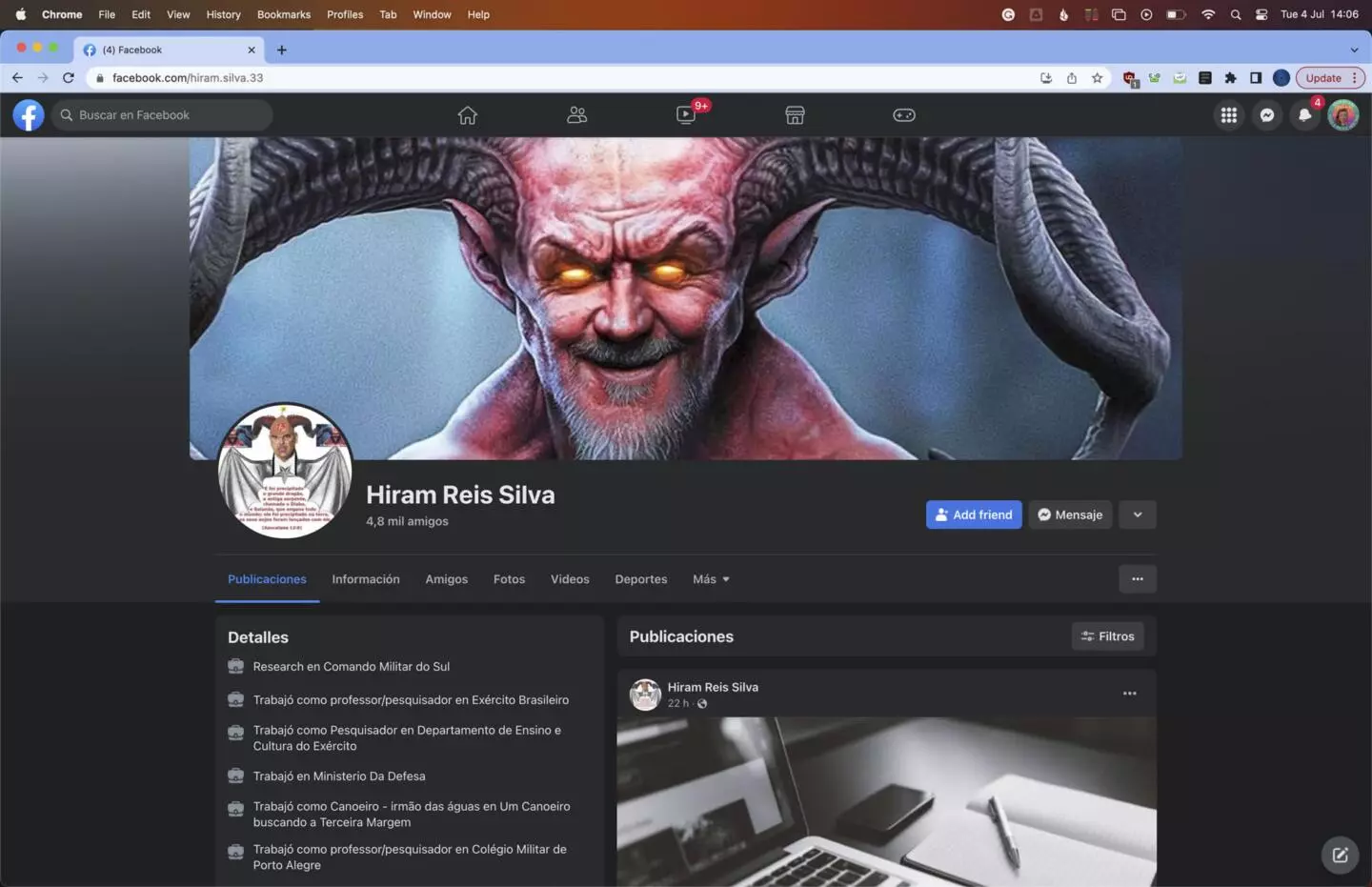

Until late April 2023, the position of the Attorney General’s Office, which is acting in defense of the Brazilian government, had been aligned with the military, anti-Indigenous, pro-Bolsonaro vision of bringing progress to the Amazon, to the detriment of native peoples. Even after President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva took office, their stance has remained the same as that of the previous government. The technical advisor appointed to the case by the Attorney General’s Office is a retired colonel whose social media profile picture is a photomontage of Supreme Court Justice Alexandre de Moraes—a prized target of Bolsonaro supporters—with devil’s horns. His role would be to supervise court-commissioned investigations and reports to elucidate how the massacres occurred. Only after questioning from SUMAÚMA did the Attorney General’s Office change their position and indicate they wished to reach an agreement.

Facebook profile picture of Hiram Reis e Silva, whom the Army appointed as the defense’s technical assistant in legal case

Federal Prosecutor Julio Araujo, one of the authors of the lawsuit, said the Public Prosecutor’s Office “is not against” negotiating with the government. If an agreement is not reached, the Brazilian government may have to finally take responsibility for the Kinja genocide. “A genocide was perpetrated on Waimiri Atroari Territory. In this case, it was sponsored by the Brazilian government, which neglected to stop the attacks or prevent escalation. There is ample evidence in the legal documentation supporting our position,” the prosecutor affirmed.

This wouldn’t be the federal government’s first conviction. In cases of genocide against Indigenous people committed during the dictatorship, Brazil was ordered to give compensation to the Krenak people in Minas Gerais, the Tenharim and Jihaui people in Amazonas, and the Avá-Canoeira people in Tocantins.

Death fired from the sky

At the microphone, before the eyes of the military, Baré Bornaldo recounted the attack on the So’o Mydy village, which unfolded in late 1974 and early 1975. “It was Marubá day, the initiation ceremony of the boy warrior. People from other villages came to take part,” he said. All of a sudden, there was an attack from above. “It was poison. They sprayed it on the maloca.” An injured Bornaldo saw, as he also said, a relative have his throat slashed.

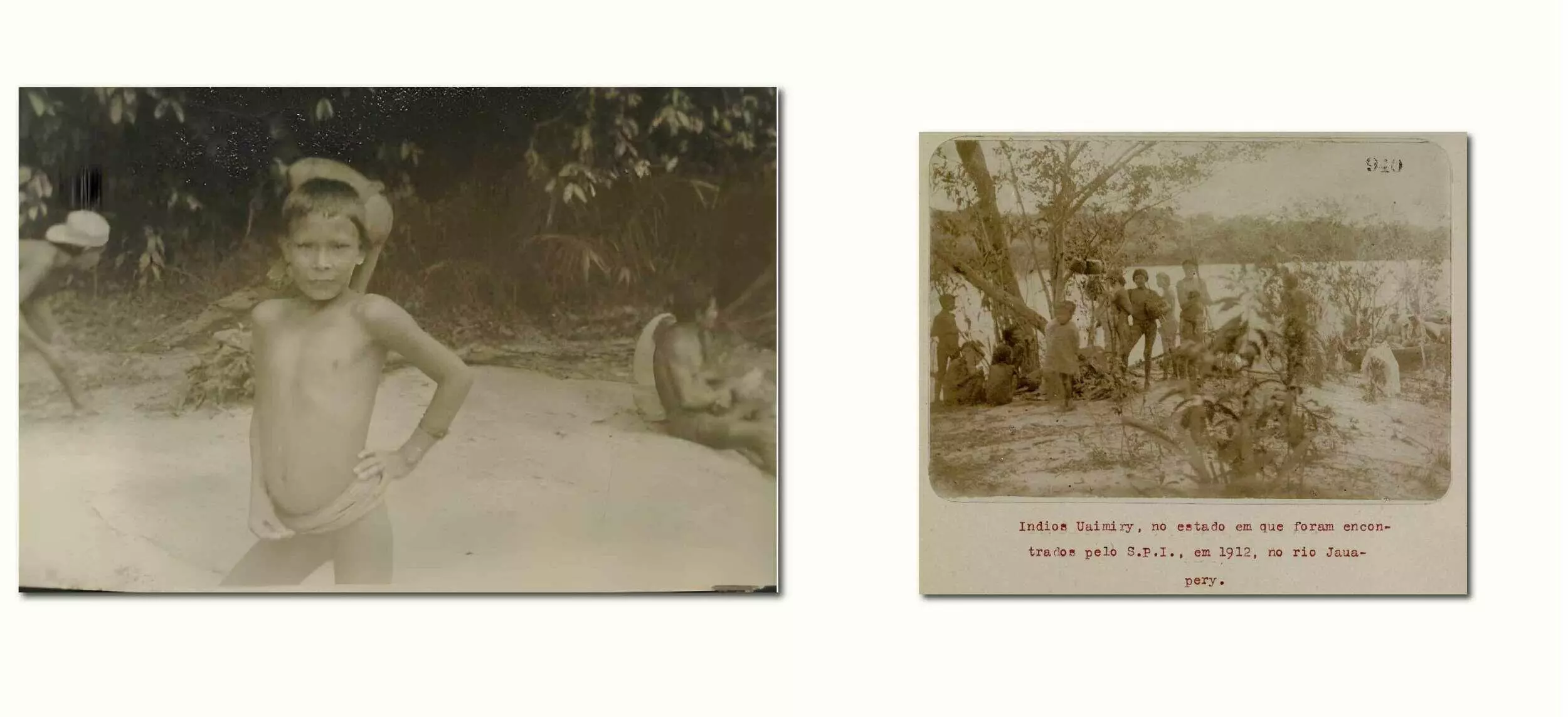

ON THE LEFT, 11 YEAR-OLD BARÉ BORNALDO IN 1969. HE WAS 14 WHEN THE VILLAGE HE LIVED IN WAS ATTACKED. PHOTO: FUNAI. ON THE RIGHT IS A 1912 PHOTOGRAPH OF THE REGION NOW KNOWN AS THE WAIMIRI ATROARI INDIGENOUS TERRITORY. PHOTO: DIGITAL ARCHIVES OF BRASILIANA FOTOGRÁFICA

As Bornaldo tells it, the Army spread terror throughout the forest. There were so many victims and so much fear of further attacks that the dead did not receive their funeral rites—to the Kinja people, this can bring a curse and other cosmological misfortunes. Baré Bornaldo testified that his relatives managed to cremate some of the bodies, but most were left behind. “There was no one left to look after the bodies,” he lamented. Another survivor, Temehe Tomas, added that fear of resumed attacks was even stronger. “They abandoned their relatives’ bodies—they were left right there.”

Manoel Paulino, then field leader for the National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples, said he witnessed the Army dig a mass grave with a backhoe loader, then bury the victims near one of the foundation’s outposts, currently the site of a village. The survivors of the attacks did not witness the burials because they were forced to flee. Paulino is a key witness in the case.

Another witness, who was heard in the anthropological investigation, gave another perspective on the events that unfolded in Baré Bornaldo’s village. Wamé Viana described a plane dispersing what looked to be water. He and other relatives were on their way to a ceremony in So’o Mydy village. When they got there, everyone was already dead—everyone but Bornaldo, then a teenager. “We saved him, in the middle of all those dead people. We got there days later. [The bodies] were already rotting, vultures eating them. When we arrived, my uncle grabbed him and took him out of there to save his life. He had a strong fever.” Bornaldo will never forget it. “When the village grew very hot, I got a really high fever. The maloca heated up. The leaves didn’t fall from the trees. It only killed the people there.” Then he said, “A whole maloca died.”

“Everything burned on the inside.”

The symptoms the Kinja people described after the chemical attacks—heat, fever, nausea, headaches, paralysis of the limbs—are “at first sight” consistent with the pathology of “nerve agents,” which target the central nervous system, according to specialist Dal Poz Neto. The Army has been charged with launching one or more of this class of chemical weapon on the villages. The victims experienced almost immediate effects: nasal discharge, coughing, rapid breathing, mental confusion, headaches, loss of consciousness, paralysis, and shortness of breath. These effects can be fatal. Among this class of chemicals is a gas called VX. Developed in the United Kingdom in 1952, VX is an odorless, relatively low-volatility substance with adhesive properties that is maintained in liquid form.

One of the survivors, who is unidentified, told the specialist what happened to the victims of the Army’s aerial attacks. “It left us confused. It attacked the village, it got hot fast. A few minutes, they died. We didn’t understand until now what weapon they used back then. It went like this: an Indian went out to hunt, then felt something like an arrow in his body. He screamed and ran to the village, already feeling the symptoms, heating up his body. It was like everything burned on the inside. He lasted a little, died. He felt an intense heat. He lay down, screaming, pouring water on his body. Not long after, he died. It’s hard for us to understand what weapon they used.”

When Baré’s village was attacked in the 1970s, poison was sprayed over a maloca where Indigenous people had gathered for a day of celebration. Photo: Raphael Alves (01/12/2017)

To the Kinja people, this was a maxi, a word in their language originally used to designate a curse or poison. Because of the massacres carried out by the dictatorship, the word has taken on new meaning. According to the report, the significance of the toxic substances the attackers used “has become more precise as our knowledge on the industrial and technology apparatus available to non-Indigenous people has increased.” Today, Indigenous people also use the term maxi to designate not only chemical and biological weapons, but also agrochemicals and pollutants.

There is evidence of at least eight military operations involving the dispersal of chemical weapons and subsequent ground invasions. After examining the patterns of these village attacks, the legal investigation concluded that everything indicated it was a “war of occupation” aimed at expelling the Kinja people from their territory.

Technical assistant of the AG Office treats Indigenous people as “incompetent witnesses”

During the judicial hearing in the Waimiri Atroari Indigenous Territory, while Baré Bornaldo described how everyone around him died from a substance that fell from the sky, a white man in the audience in civilian garb shook his head in a show of frustration. The man in question is retired colonel Hiram Reis e Silva, a military officer aligned with the Armed Forces’ anti-Indigenous ideology. He was in the room because the Army appointed him as “technical assistant” to the Attorney General’s Office’s defense team. Selected in January 2019, the first year of retired captain Jair Bolsonaro’s extreme right-wing government, his role was to oversee the anthropological investigation.

Even though President Lula took office in January of this year, retired colonel Reis e Silva was still representing the federal government as of the completion of this article. After questioning from SUMAÚMA, the Attorney General’s Office began the process of negotiating a settlement with the Public Prosecutor’s Office. However, it has yet to formally request Reis e Silva’s removal from the case.

Reis e Silva served in the Amazon’s Battalion of Construction Engineering, which is responsible for part of the construction of highway BR-174. He did not serve during the period of the attacks, but more than five years later, between 1982 and 1983. The 72-year-old military office also worked as a math teacher at the Colégio Militar de Porto Alegre and claims to be the president of SAMBRAS, the Society of Friends of the Brazilian Amazon, an NGO whose National Registry of Legal Entities number is in the name of Hilda Wrasse Zimmermann, from Rio Grande do Sul, who died in 2012. Since 2018, Brazil’s Special Department of Federal Revenue has deemed SAMBRAS unfit, citing lack of documentation. The organization’s website is no longer online.

The retired military officer Hiram Reis e Silva, appointed as the defense’s technical assistant in legal case, holds anti-Indigenous views and supports occupation of the Amazon. Photo: Omar Freitas/Agência RBS (29/05/2015)

It was thanks to a partnership between the military academy and SAMBRAS, Reis e Silva claims, that he was able to travel by kayak along the rivers of the Amazon basin in 2008 and 2009, between the cities of Tabatinga in Amazonas state, and Belém, in Pará. From his trips through the Amazon, the colonel has written various books, all self-published online. In one of them, titled Defying the River-Sea – Descending the White, Volume III, he says, in reference to the demarcation of Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous Territory, ratified by the Supreme Court of Brazil in 2009: “The decision [about the demarcation] has but one sad, melancholic meaning—to put Brazilian sovereignty at risque (sic). The territory currently belongs to an ‘indigenous nation,’ and no so-called ‘non-Indians’ can live or even pass through there, because the perverse agents of the Indigenist Council of Roraima do not consider them Brazilian kin.”

Judging by his Facebook posts, Reis e Silva is a Bolsonaro supporter. He shares memes that express a desire to run over Lula and the Supreme Court Justices, videos with messages to the tenor of “in case some clueless asshole tries to talk shit” and tendentious news items according to which “if the time frame [for the demarcation of Indigenous territories, a favorite talking point of the ruralist bloc] collapses, it will spell the end of private property.”

Reis e Silva showed his frustration about the testimony of the Kinja survivors during the hearing in the Waimiri Atroari Indigenous Territory. A few days later, he made his position even more explicit. In an online document dated March 2019 and titled “Circus of Horrors,” he states that the lawsuit filed by the Public Prosecutor’s Office is “rife with ideological bias, hinges on the testimonies of a few incompetent witnesses, and lacks any conclusive proof.” The Public Prosecutor’s case rests not only on the testimony of Kinja elders, but also on those of Indigenous experts and respected anthropologists like Stephen Baines, a professor at the Universidade de Brasília, and Egydio Schwade, one of the founders of the Indigenist Missionary Council.

Reis e Silva’s attitude during the hearing led the Waimiri Atroari people to successfully request his interdiction from their territory to oversee the legal investigation. “The leaders and other members of this ethnic group are keen observers. They registered Reis e Silva’s negative behavior and expression, which greatly disappointed them,” stated a July 22 petition from the lawyers of the Waimiri Atroari Community Association to the Federal Court of Amazons. “The Kinja people felt they were being portrayed as liars, which to them is a very serious accusation, since in Kinja culture, lying is inconceivable and vehemently rejected,” the petition continues.

The document then concludes: “[The Kinja people] refuse to allow access to their territory to someone who behaved negatively when a Kinja Warrior, an elder, gave testimony under oath, and who later insinuated to the press that the Kinja people were being untruthful.” The document is referring to an interview Reis e Silva gave to the Associated Press after the hearing, in which he claimed to “have another version of the facts.”

Faced with objection from the Kinja people, the Attorney General’s Office and Public Prosecutor’s Office agreed to keep their technical assistants out of the investigation, a decision ratified by the judge in 2022.

SUMAÚMA spent over 40 days trying to interview Reis e Silva. He didn’t respond to a note sent to an email address available online, nor to direct Facebook messages. The Colégio Militar de Porto Alegre, where the retired colonel used to teach, refused to share his phone number. At the request of the media sector, SUMAÚMA sent the institution an email stating they wished to speak with the colonel for a news article and requesting his contact details. The Colégio Militar said they did not have the former teacher’s contact information. Messages were also sent to an email address available online and to a cellphone number said to belong to the colonel’s wife. There was no response.

According to the Attorney General’s Office, the colonel was appointed to oversee the case by the Army and claimed it “took into consideration the difficulty of finding other professionals with knowledge of the case who were capable of providing clarifications that could be used to settle this controversy, especially in light of the time that has passed since the events cited in the reports.”

The Army, on the other hand, stated in a note to SUMAÚMA that it “is unaware of any events or conduct on the part of the technical assistant during the 2019 hearing that could be viewed as disrespectful to Indigenous people” and that “respect toward Native peoples has been built into the Army’s institutional culture since its inception.”

SUMAÚMA used the Access to Information Act to request from the Army a copy of the documentation appointing Reis e Silva. The request was denied: “This documentation, which is covered by attorney-client privilege, refers to procedural strategies and cannot be disclosed.”

The AG Office’s Bolsonaro appointee keeps his position under President Lula

On April 27, 2023, nearly five months after President Lula and Attorney General Jorge Messias took office, the Attorney General’s Office began their critique of the investigative report and the allegations made by the Public Prosecutor’s Office. It also reaffirmed that Hiram de Reis e Silva should be heard as technical assistant of the defense.

“Although the federal technical assistant’s involvement in the investigation has been called into question, it is important to note that in light of the limited staff and the time elapsed since the events in question, the Attorney General’s Office reached out to a professional with knowledge of the case, capable of forming well-founded reflections attuned to the circumstances of the time”—this sentence is underlined in the piece signed by federal attorneys Ivo Lopes Miranda, Luis Fernando Teixeira Canedo, and Israel Sales Vaz.

The Attorney General’s Office also suggested another retired colonel be included as a witness, “with the aim of shedding light on questions about the Armed Forces’ planning and execution of operations in the time period and locations that pertain to the case.” The man in question is Gélio Fregapani, ex-commander of the Jungle Warfare Training Center. According to a 2005 news article published in O Estado de S. Paulo, Fregapani—then an employee of the Brazilian Intelligence Agency—prepared a report in which he made clear that demarcating the Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous Territory would trigger a “military response.” “All signs point to environmental and indigenous problems being mere excuses, and that the main NGOs are in fact pieces of a larger game in which hegemonic nations strive to maintain and expand their dominance,” states an excerpt of the report cited in the news article. “They are clearly cover-ups for their secret services.” Years later, in 2014, in a blog about military issues, Fregapani would write that the Army should view illegal gold prospectors as “allies” and “key to the success” of their regional policies.

The Waimiri Atroari people, as they are known, call themselves Kinja, meaning the “true people.” Photo: Raphael Alves (26/2/2018)

SUMAÚMA reached out to the Attorney General’s press contact to inquire about federal attorneys Ivo Lopes Miranda, Luis Fernando Teixeira Canedo, and Israel Sales Vaz’s position about the petition where they reiterate their support of Hiram Reis e Silva and Gélio Fregapani. In response, they were informed that public servants do not speak to the press.

Is a “conciliatory solution” possible in genocide cases?

On May 11 of this year, the Attorney General’s Office changed their position, asking the judge on the case to drop the public civil suit “with the view to begin conciliatory negotiations with the Public Prosecutor’s Office. The moment Attorney General [Jorge Messias] learned about the impasse between the Indigenous people and the Army-appointed specialists, he personally decided to seek a conciliatory solution,” the Attorney General’s Office stated in a note to SUMAÚMA. “The AG Office’s leadership understands that a conciliatory solution is not only possible but preferable to continued litigation.” This change of position occurred after SUMAÚMA contacted the department—in April—seeking an explanation about its stance on the Waimiri Atroari people’s case, since it was closely aligned with that of the former government.

A source close to the Attorney General revealed, on condition of anonymity, that the case was being treated “bureaucratically” by the AG Office and that a change of position is natural after “a drastic swing” like the one that occurred in the transition between the governments of Jair Bolsonaro and President Lula. After this change of position, the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples and the Army were contacted with the aim of reaching a consensus proposal. An agreement, however, may be hampered by the Armed Forces’ insistence that they are not responsible for any crimes committed during the dictatorship.

The Attorney General’s Office’s change of position was met with skepticism by the Public Prosecutor’s Office. Prosecutors familiar with the case told SUMAÚMA that the Attorney General would have to demonstrate, in practice, how they plan to achieve a consensus solution. “It’s worth remembering that statements made by the Office of the Attorney General have been aimed at deconstructing the events that led to the present suit,” federal prosecutor Fernando Soave emphasized. “Recently (in 2023, under the new government), the AG Office disagreed with the content of the investigative report, asserting that the results do not demonstrate any illicit behavior on the part of the central government.”

As of completion of this article, the judge on the case has yet to decide whether or not she should accept the Attorney General’s Office’s request and the Public Prosecutor’s Office has asked “for further clarifications as regards any deliberations” about a potential agreement. Whether or not an agreement is reached, the lawsuit is ready for an initial ruling.

The decision could represent the end of a period of horror for the Kinja people, who continued to be targeted after the war of occupation the Army waged for the BR-174 highway. Following their forced removal, survivors lived near Brazil’s federal agency of Indigenous affairs’ post for the attraction and pacification of Indigenous people, which caused a large number of epidemic deaths and where survivors were subjected to forced labor. Later, a large portion of their territories was granted to the Taboca mining company, of the Paranapanema group, and to land invaders who settled on the side of the highway during the dictatorship. Another part was flooded by the Balbina hydroelectric dam and power station during José Sarney’s government (1985-1990). Whole villages were evacuated.

During the Bolsonaro government (2019-2022), the Kinja people were pressured to agree to the construction of a new high-voltage overhead power line between Tucurí and Boa Vista, once again cutting through Indigenous territory. The Kinja genocide case could be an inflection point in a series of violent acts that persists to this day.

Indigenous leaders have requested that all massacre sites be recognized and designated as sacred—locations that would have to remain undisturbed. “They came with the BR [highway], they came with the asphalt, they came with topographical studies, which brought us problems. Now, that big [power] line. This is very sad for us. A sign would be OK, anything to protect the place, to keep it from being touched anymore. So the white man knows it’s not allowed. The Waimiri Atroari people will never forget what happened,” Kinja leader Parwe Mario said in the hearing held at the Federal Court.

“I want to talk about a sacred area for the Waimiri Atroari people,” Ewepe Marcelo pleaded. “Where blood was spilled, there is now an unforgettable mark.”

Fact check: Plínio Lopes

Spell check (Portuguese): Elvira Gago

Translation into Spanish: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Julia Sanches

Photography editing: Marcelo Aguilar, Mariana Greif and Pablo Albarenga

Page setup: Érica Saboya

Ant trees in flooded area near Waimiri Atroari Indigenous Territory. Photo: Raphael Alves (01/12/2017)