Osvalinda Alves Pereira lives one-tenth of a second away from death. Afflicted with a disease that has been aggravated by her struggle to keep the forest standing, her 55-year-old heart sometimes skips a beat – or two or three – and she freezes, putting her hand to her chest. When she added her name to the waiting list for a pacemaker, the doctors said that if her heart paused for another tenth of a second, it could be fatal. The diminutive Osvalinda has big eyes, green like the forest she protects, and hands calloused from a lifetime of work in the fields. Her family is one of seventy living in the Areia II Resettlement Project, built in 1998 in the municipality of Trairão in southwestern Pará state. She became a defender of the environment and of land rights in Brazil’s deadliest state, which has the highest rural murder rate and is one of the most dangerous regions in the country for defenders of any kind of right. For ten years, Osvalinda heard threats from men intent on plundering the forest where she lives. Then, in 2018, she and her husband went out one morning to gather passion fruit and found two holes dug in the ground—open graves marked by crosses, each bearing a name: his and hers. She froze, putting her hand to her chest. Whoever was threatening the couple was no doubt watching and could kill them right there, in one-tenth of a second.

“I thought I was just about dead, me and my husband. That would crush anyone’s heart. Everything turns to rags,” she says. Osvalinda, a recognized rights defender, has been featured in countless news stories–and one documentary–portraying the lives of people who have been threatened because they fight for agrarian reform in Pará. She heads the Areia II Women’s Association, and in 2012, alongside her husband, Daniel Pereira, 52, she began denouncing both illegal logging activities inside of resettlement projects, as well as the public land theft scheme known as grilagem. The streets of Areia II serve as thoroughfares for trucks loaded with logs stolen from three nearby conservation units: Trairão National Forest, Riozinho do Anfrísio Extractive Reserve, and Jamanxim National Park. In 2014, four years before Osvalinda and her husband found the backyard graves, they received so many threats that they entered the federal government’s protection program for human rights defenders. But the program hasn’t protected Osvalinda and Daniel enough for them to live in peace. They have no police escorts or any security equipment protecting the home where they live. And the criminals can come as close as they want.

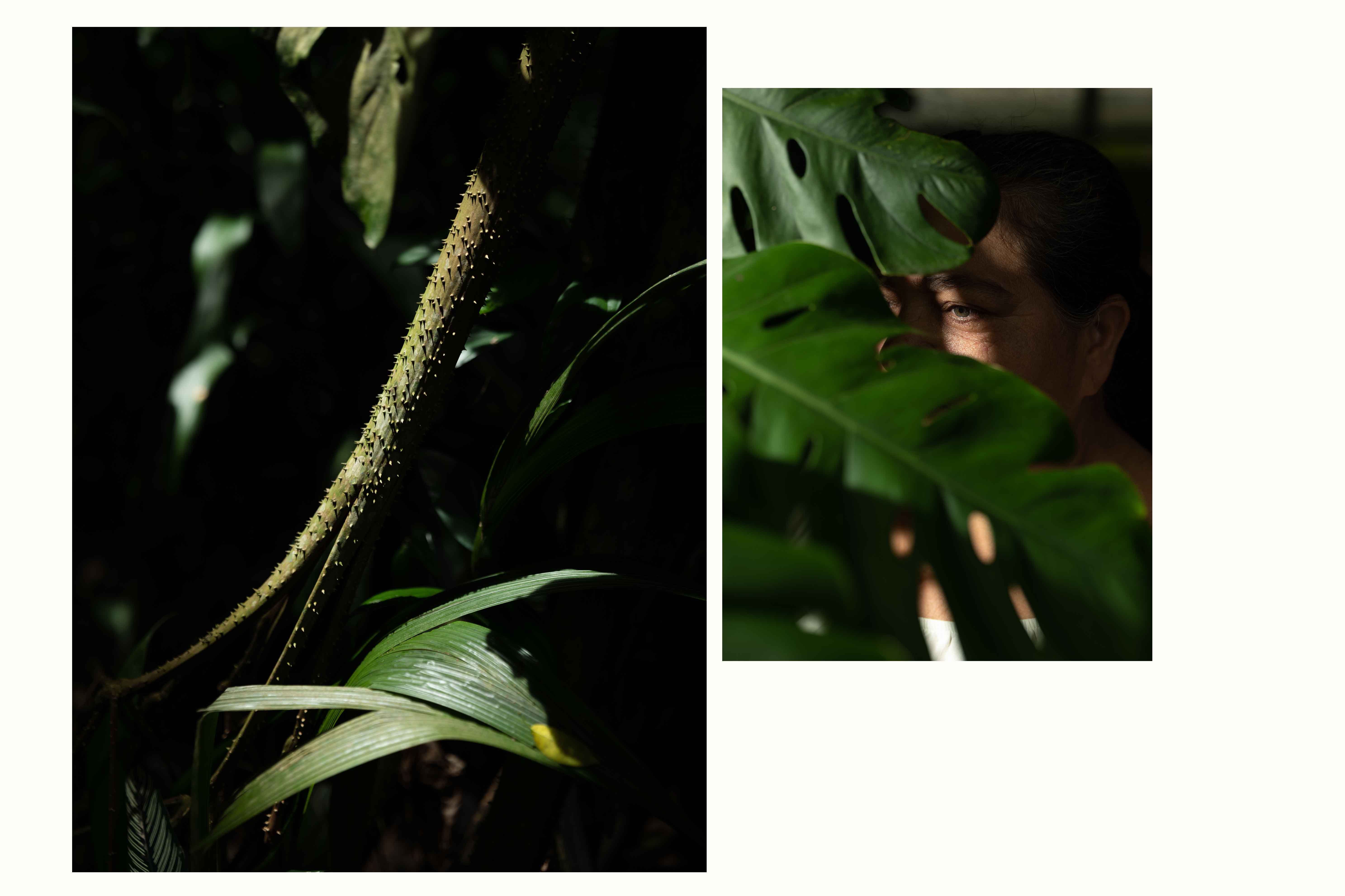

Osvalinda and Daniel, leaders threatened with death by illegal loggers and now in the protection program for human rights defenders, pictured in a forest in Pará. Photo: Alessandro Falco/Sumaúma

Established in 2004 by Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, then in his first term as president, the program gained a new name in 2018: the Protection Program for Human Rights Defenders, Communicators, and Environmentalists . Its role, however, stayed the same: to provide security so rights defenders can remain in their places of residence. In extreme situations, when the risk is especially high, the program is supposed to transfer threatened individuals to temporary lodgings in a secret location until things settle down and they can return. Under the law, the federal government can sign agreements with individual states interested in setting up their own programs. In 2019, Pará opened one such program, managed by the nongovernmental organization Society, Environment, Education, Citizenship, and Human Rights.

But program guidelines fall short of needs, and the defenders who should be protected in their places of residence lack suitable protection, while the defenders who need to be moved from their homes and relocated to temporary lodgings suffer indignity. Over the last two months, we interviewed six families of rights defenders who are part of this program in Pará. We saw sick people who had no access to adequate medical care and were living in temporary houses infested with mould, where sewage was backing up into the drains. These individuals, now living far from their fruit and vegetable patches, sometimes didn’t have enough money to feed their families. Unprotected, they live in constant fear in a state where, from 2013 to 2022, 98 people were murdered and another 127 were victims of murder attempts, according to data from the Pastoral Land Commission. Deaths in rural Pará account for one-fourth of murders in rural areas in Brazil.

Erasmo Theofilo, an environmentalist threatened with death in Anapu, Pará, and his two-year-old son. His family remains in exile after a death threat forced them to leave their place of residence. Photo: Alessandro Falco/Sumaúma

In light of this, a group of human rights defenders in Pará has begun organizing a new struggle, this time for the right to be truly defended. Under the umbrella of the new association, these defenders plan to present the federal government with a series of demands meant to enhance the protection program. This includes the construction of walls and the installation of security and surveillance systems in defenders’ homes, along with adequate health care and financial assistance so they can live with dignity when they need to leave their places of residence. The group is also calling for the provision of funds so defenders can be relocated permanently when forced to abandon their communities for good. Next month, they will present these demands in Brasilia, where the federal government is preparing to convoke a work group to discuss the program (further information below). “We want a federal law that will really protect human rights defenders, like the Maria da Penha Law [for female victims of domestic violence],” says Natalha Theofilo, a member of the new association.

M.A. is part of the group. She is a serene, soft-spoken woman who almost became another statistic in this horror story. Although she is part of the program, she lives unprotected in a quilombo [community of descendants of enslaved Africans who rebelled] that was invaded in 2020 by land-grabbers with ties to a drug trafficking faction in Brazil. Given the absence of oversight in the Amazon, the criminal group saw the invasion of public lands as a lucrative new business. When the land thieves reached the territory, many quilombolas [residents of quilombos] fled, including the president of the local association. This is when M.A. took over the group and began denouncing these crimes. (Her name is being withheld in this article for security reasons, at her request).

Detalhes da casa de uma defensora dos direitos humanos ameaçada. Foto: Alessandro Falco/Sumaúma

“At first, we didn’t know they were faction members. We only knew they were deforesting everything and building on land near the quilombo. But when they got closer to our community, I went after them and said, ‘Not here’,” M.A. recalls. Sitting in a plastic chair, two rosaries wrapped around a glass bottle at her side, she talks about her encounter with terror while we listen to birds sing and the rain fall. One November morning last year, she was at home, busy organizing paperwork related to the purchase of solar panels for local residents through a project. “I heard the sound of a motorcycle, and when I went outside, I saw a young guy in the front yard. He said, ‘Come out here, because what I’ve come to do is really fast’. It never occurred to me he might be armed, and before I could realize it, he pulled out a gun and said, ‘Look, I’m going to warn you: don’t mess with us, because if they come after anyone from the faction, I’ll come back and kill your whole family’.” M.A.’s daughter, 22, let out a terrified scream. Before the neighbors arrived, the man climbed back on his bike, repeating, “You’ve been warned.” Now the woman stops speaking every time a motorcycle approaches.

After receiving this threat, M.A. entered the protection program—but they changed nothing at her home or in her routine. The walls surrounding her house are still low, and she took it upon herself to buy a second-hand security grille for the front door. “Everybody said, ‘For the love of God, you have to leave; you have to get out of here’. But I’m not going to leave my home. I’ve got a lot to do for my community.” Paradoxically, she has felt more protected since a police officer was killed inside the quilombo during a confrontation with criminals, because now there are more police patrols. “When it was only the quilombo that was threatened, the police weren’t doing much. But now that an officer has been killed, things have calmed down,” she tells us.

M.A. on a walk near her home, where roads flood regularly on rainy days. Photo: Alessandro Falco/Sumaúma

Imprisonment for the sake of survival

Maria do Socorro Costa, 57, lives in a quilombo in another region and has been in the protection program since 2018. She also asked the program to beef up security where she lives. “What did they do? Did they put a wall around my house? A camera? None of that!” she says. They told her there were no funds. “Being in the program is just talk. It’s just paper,” she complains. She installed six security grilles in her house. “I bought them,” she tells us. Socorro opens the door, and we walk through the first, which leads to a covered space crammed with documents from the quilombo association she heads. Another five grilles separate each room in the home, tantamount to a prison. Out back, the chickens peck away, oblivious to the danger.

Socorro (in the background), a quilombola leader who is in the protection program for human rights defenders, pictured with her sister (likewise in the program) in Socorro’s home in Barcarena, northeastern Pará. Photo: Alessandro Falco/Sumaúma

In recent years, Socorro has received death threats via text messages, been chased by cars, and even spotted drones flying over her house. “The state and federal government are complicit with them. I don’t want to die, but I have to be mature. If I don’t want to die, I have to give up the struggle. And if I give up the struggle, I’ll see more people die.”

Socorro’s backyard hints at the complex struggle she faces. Chickens scratch about under trees where the fruit has rotted on the branch before it has time to ripen. “They get like that because of the contaminated soil,” she explains, pointing to a dead açai tree. She shows us the rest of the yard: rotting coconuts, trees with burned leaves, peach palm fruit that barely sprouts before it dies. Wearing a red dress and her trademark straw hat, holding a hand-rolled cigarette between her fingers, she puts her hand behind her glasses to rub her inflamed eyes. “We’re always sick around here. We didn’t have much before, but we were happy. Now we don’t have a river to fish in and the land is what you see,” says Socorro, who is known as Socorro do Burajuba, named after her quilombo of some eight hundred families. Burajuba lies in Barcarena, a municipality in the state of Pará, an epicenter of the toxic exploitation of the Amazon.

Barcarena is the site of the Hydro Alunorte alumina refinery, owned by Norsk Hydro, a Norwegian multinational headquartered in Oslo. The plant processes and then exports aluminum made from bauxite extracted from a mine in another municipality and piped underground to Barcarena. Part of the material is then refined there–where two tailings deposits lie right next to the community of Burajuba. Likewise located in Barcarena is the French multinational Imerys, which operates the world’s largest factory for processing kaolin, a mineral used to manufacture a wide range of products, from plastic and rubber to cosmetics and sanitary napkins. In addition to these two multinational giants, this port on the Pará River is home to companies in the shipping sector and plays a strategic role in the transportation of soybeans. Barcarena is also the site of fertilizer companies that supply the region’s robust agribusiness sector. “Many people have their eye on Barcarena, and these companies are contaminating our soil and water, disrupting our way of life, our existence. My husband died, a victim of contamination. Thousands of people are dying every day because of this contamination, and everybody shuts their eyes to it,” she says. “We quilombolas, ribeirinhos [members of traditional forest communities], everybody—these companies and even the government see us as getting in the way.” As the leader of the Association of Caboclos, Indigenous, and Quilombolas of the Amazon (Cainquiama), an organization that campaigns for the rights of traditional communities, Socorro denounces every case of environmental pollution and grilagem that she uncovers.

In February 2018, people in thirteen ribeirinho communities that depend directly on the Bom Futuro and Burajuba tributaries and the Murucupi and Tauá rivers, all part of the Pará River basin, noticed red mud oozing into their yards and artesian wells. Analyses of the liquid by Marcelo de Oliveira Lima, a public health researcher with the environmental division of the Evandro Chagas Institute, ascertained that the liquid contained mining residue and was contaminated with lead and other heavy metals found in the municipal water supply, caused by Hydro Alunorte. “We were all desperate then, during the leak and afterward. Everybody was sick, contaminated,” Socorro says. Hydro Alunorte has denied the leak. Given the visibility of this case and Socorro’s denunciations of land theft, life became riskier that year. Two quilombola leaders were shot to death.

Socorro entered the protection program but, she maintains, nothing has changed. The police will occasionally make a perfunctory drive by her house. She has the phone number of the Military Police Battalion in case of emergency. “When I call the station, sometimes they say they have only one police car. It takes them a while to get here. The State knows I’ve got poison in my blood, that I’m doing what government officials should be doing, but even so, they don’t do anything,” she says, short of breath from her constant coughing. “I don’t want to leave. If I leave, who will fight for them? Not to mention, if they move me out of here, I’ll be so sad I’ll die. What everyone needs to understand is that we, the ones who are here, are the Amazon. If there is an Amazon today, it’s because of us. If anyone has to leave, it should be the companies; they need to learn to respect my people.”

Socorro, quilombola leader of the community of Burajuba, in Barcarena, northeastern Pará

Broken bodies

Every day, the defenders that were heard and visited by SUMAÚMA protect the world’s largest tropical rainforest, and the planet’s climate regulator, with their own bodies. They confront powerful enemies like transnational corporations and local hatchet men with ties to the political elites in their municipalities or Brazil’s centers of power. The police are often allies of the defenders’ very enemies, as are local physicians, who block access to health services. Treatment frequently comes too late for sicknesses triggered by violence or worsened by constant stress.

Osvalinda, leader threatened with death by illegal loggers, pictured in a forest in Pará. Photo: Alessandro Falco/Sumaúma

“In many municipalities in rural Pará, college-level posts—like that of physician, nurse, psychologist, nutritionist, secretary of public security—are generally filled by people with ties to local power. And these defenders stand up to local powers. That’s why many defenders report that the problems start right there, at the local level. How are you going to be seen by a psychologist who is a relative of the person you’re fighting? To skirt this system, we sometimes take the person to another municipality for care,” says the prosecutor Ione Nakamura, representative of the State Public Prosecutor’s Office on the protection program board in Pará. “We got the Department of Human Rights to set up a policy, but it’s not enough. It has to be part of other public policies, which also have to have a norm, an adjustment, so these defenders have greater access to more effective services,” Ione says.

Maria Márcia de Mello, who has stood up to invaders in the settlement project where she lives, has suffered three attempts on her life, two of them after she entered the protection program for human rights defenders. Photo: Alessandro Falco/Sumaúma

Maria Márcia de Mello, 46, is head of the Nova Vitória Association of Rural Producers, part of the Terra Nossa Sustainable Development Project. Established in 2006 by INCRA, Brazil’s agrarian reform agency, Terra Nossa lies between the municipalities of Altamira and Novo Progresso, where 310 families plant passion fruit and cupuaçu, produce honey, and raise chickens and pigs—and where five people have been murdered since 2011. This stark brutality stems from the invasion of public land thieves and fazendeiros [large farmers and ranchers], who deforest the land to plant soybeans or raise cattle; it is also a product of the onslaught of illegal miners and even multinationals. SUMAÚMA recently showed that the British mining company Serabi Gold has begun operating a gold mine inside the territory, without the authorization of the state’s agrarian agency or any consultation with residents or Indigenous communities. Although the region is treated like a no-man’s-land, it has many owners, represented by Maria Márcia, who has been challenging and denouncing all these invaders without backing down, even after she experienced three attacks, the first in 2019, when she entered the protection program. But even though she was in the program, it didn’t keep these criminals from trying to kill her two more times.

The last time was in May 2022. For some reason, Maria Márcia woke up with her hands and face swollen. “I called the program and took a photo. They said I should have it looked at. Our car had traveled a kilometer inside the settlement when three pickups without license plates pulled up—one red, one white, and one gray. They signaled for us to stop, and several men wearing camouflage jumped out, armed with rifles,” she remembers. “When I got out of the car, my three-year-old grandson Pedro clutched my neck, and the older one, José Armando [9], started screaming, ‘Don’t kill my grandma! Don’t kill my grandma!’” she says. “I think the only reason they didn’t kill me there was because Pedro was clutching my neck.”

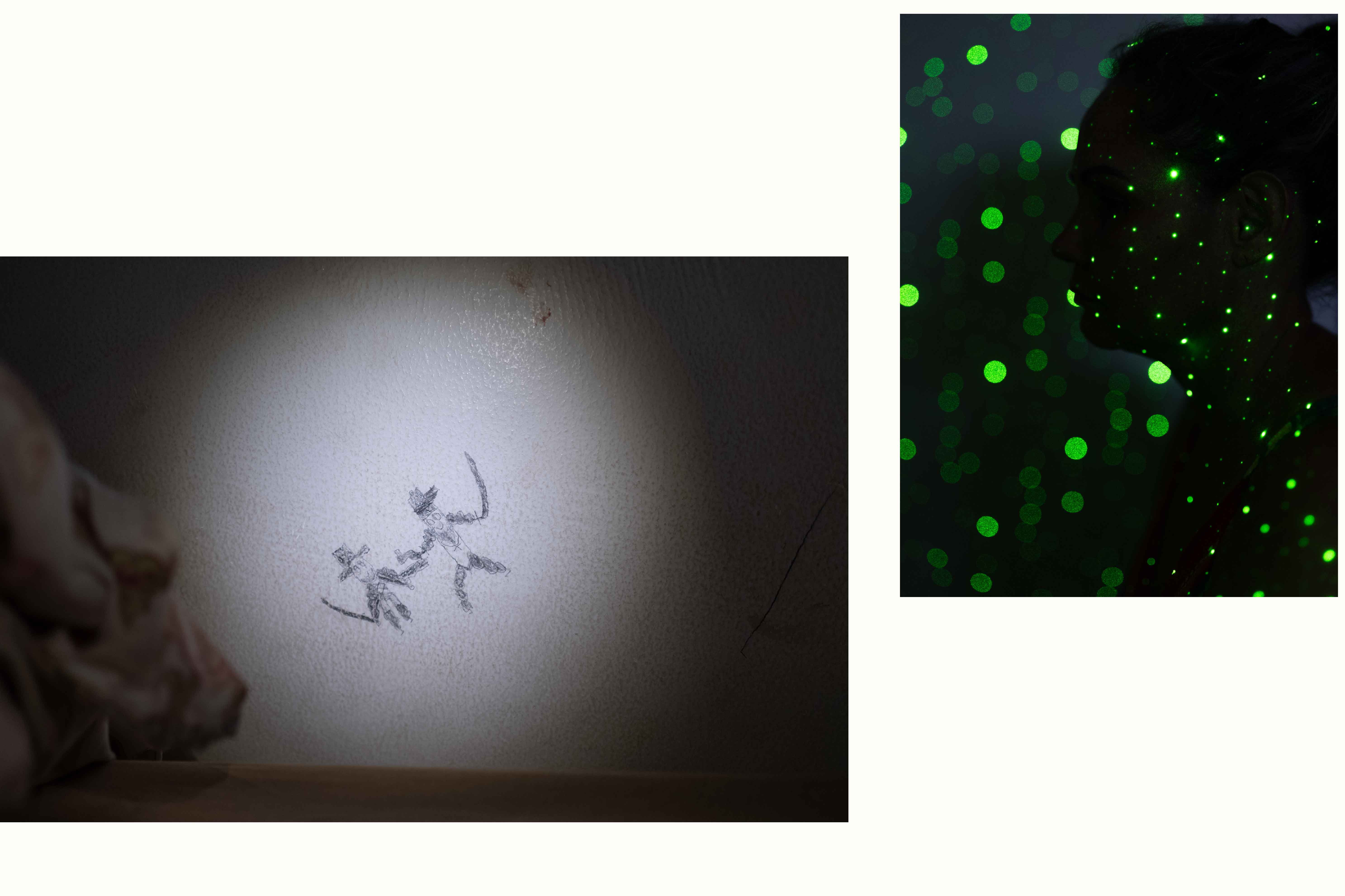

Drawing of two gunmen by Maria Márcia’s grandson, who witnessed the attempted murder of his grandmother, a leader threatened with death by large landholders (left). Picture of Maria Márcia (right). Photos: Alessandro Falco/Sumaúma

Ever since the first attack, in 2019, Maria Márcia has struggled with serious health issues. “The first time they tried to kill me, my husband and I were going to the wedding of one of my daughters. I noticed there was a pickup following us and I thought, ‘Today’s the day we die’.” There was a chase. “It all happened very fast, and the road was narrow. Our car flipped over.” She has been in constant pain ever since. “At the time, I couldn’t walk.” She broke her pelvis and spine, but only found that out when her friends passed a hat to pay for private health care, after watching her agonize in pain for weeks. At the nearby public hospital, right after the accident, she says the doctor, who was friends with some local fazendeiros, barely examined her. “I went through all that and told the program about my situation, but the only thing they said was ‘We’re scheduling an appointment, we’ll get you out of there’. Then nothing happened, and there I was in pain. It was awful. I spent three months unable to walk.”

In February, the program took her to another city for treatment. They lodged her and her two grandsons, who live with her, in an efficiency apartment with a tiny kitchen, one bathroom, and a laundry area with only enough space for a washing machine. Sometimes she barely has enough to eat because the program’s financial assistance doesn’t cover her expenses. SUMAÚMA finally interviewed her there (we are keeping the name of the city confidential), after waiting weeks for her to recover from a disabling toothache that caused tremendous swelling, deforming her face and leaving her unable to speak. “I spent weeks asking the program for help with my tooth, but it was only after I contacted the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office that they took me to the hospital. That’s how the program works,” she says in frustration. “Ever since I got here, my grandsons have been out of school because the program hasn’t enrolled them, and I can’t.” The program denies that it failed to enroll them.

Inside the home of an anonymous woman who is in the protection program for human rights defenders and has received threats from a criminal faction in Pará. Photo: Alessandro Falco/Sumaúma

Children suffer more

Natalha Theofilo, 34, is a tall, Black feminist, quilombola, human rights defender, African hair braider, and teacher. She had to abandon the region with her partner, Erasmo Theofilo, and four youngest children, ages two to nine; Ingrid, 18, joined them later. They were forced to flee when Erasmo, who had already received several threats, got an audio message on WhatsApp that read: “You don’t have to worry about dying anymore because we’re not going to kill you. We’re just going to rip your heart out.” According to Natalha, in Anapu, where they lived at that time, if they say they’re going to rip your heart out, it means they’re going to attack your child, or the people you love most. “By heart, they were talking about my children. I was never so scared.”

Erasmo and Natalha Theofilo, leaders threatened with death in Anapu, pictured in the kitchen of their temporary home, which floods during heavy rains. Photo: Alessandro Falco/Sumaúma

Erasmo, 34, displays a picture of their home on his broken cellphone screen—a house surrounded by trees in Plot 88 of the Bacajá tract. He moved to rural Anapu with his parents in 2010. “We thought life would be more tranquil there.” He had polio as a child and by the time he was ten had undergone nineteen operations. At the age of sixteen, he became the first president of the Transamazonian association of people with disabilities. He also became a leader of small-hold farmers, an environmentalist, a human rights defender, and an agroforest systems educator. He earned his bachelor’s degree in administration and a graduate degree in government management. From 2013 to 2016, thanks to political organizing efforts and the community’s hard work, three rural settlements were legally recognized within the municipality, including the one where Erasmo and Natalha’s family lived, at kilometer 80 of the Transamazonian highway. After joining the fight for the legal recognition of other territories, they became targets of public land thieves and saw two of their comrades in the struggle murdered. Although Natalha has received repeated threats, only Erasmo is in the protection program; she has never managed to get in.

The program placed the family in a three-bedroom house with two bathrooms, a kitchen, utility area, patio, and porch. On paper, all apparently quite decent, but a more discerning look tells a different story. Almost all the inside walls are covered in mold; in the kitchen, what’s left of a fungus-infested cupboard is consumed by humidity; in the bathroom, a toilet not properly fastened down spills waste with every flush and when you use it, you have to be careful not to hurt yourself; the shower faucet has to be opened with pair of a pliers.

“We’ve complained to the program about the shape of this house many times, but they say they can’t do anything and that that’s how things are,” declares an indignant Natalha, pointing to the moisture on the wall. In the backyard, a warped, termite-riddled beam forewarns that the roof might cave in. When it rains, the yard floods and water enters the house. The NGO that manages the protection program told SUMAÚMA that the problems were caused by rain and had already been taken care of. But we visited the place twice, in March and early April, and the situation remained unchanged. Natalha has also been trying for months to get an appointment with a gynecologist, because she has experienced frequent bleeding. “Health care is terrible in every imaginable way. There’s no help with medicine, with anything,” she says, exasperated. “Our situation here is very complicated. As you can see, the house doesn’t offer decent living conditions, and we don’t get enough money for our monthly support.”

Empty refrigerator in the home of Erasmo and Natalha, who had to relocate from their permanent place of residence after a death threat. Photo: Alessandro Falco/Sumaúma

The tract back in Bacajá had four reservoirs and two headwater springs, with lots of fish. “The children’s entertainment was to go fishing with their parents and grandparents. We had a lot of chickens in the yard too, for meat and eggs,” says Natalha. “There was plenty of cassava, corn during corn season, beans during bean season, cupuaçu, pineapple, Brazil nuts, cashews, biribas, hog plums, tamarinds, jaboticabas, peach fruit palms, coconuts, all kinds of mangos, ice-cream beans, oranges, Brazilian cherries,” she lists. “We use the agroforest system, which gives you all sorts of fruit. We lacked nothing. We were very happy, and the children hardly ever got sick.” They don’t believe they’ll ever get back to this place, and they don’t know what they’ll do in the future, since the program isn’t offering any solution. “We’ve been here seven months now. We’ve complained and we’re going to file a lawsuit against the government. They’ve given us no prospects for the future. The program asks us, ‘What are you going to do?’ But if we go back, we’ll die,” she says.

They fight for land they can’t live on

This angst is shared by the family of S.R., a farmer who has been caught in a tremendous legal mess. On the one side, a powerful grileiro [public land thief]; on the other, INCRA, Brazil’s agrarian reform agency. The area where S.R. lives was declared public land and earmarked for agrarian reform, but this has been contested by a grileiro, who claims he purchased the place and has the right to live there. Two hundred fifty families reside there now, making a subsistence living by working the land. S.R. planted 15,000 cacao trees, 3,000 annatto trees, 250 black pepper plants, and more than four hundred banana trees with the help of his family, comprising some thirty members, including children and grandchildren. “We dreamt about having a really nice cacao farm someday, which we could live off,” he says. “But then we had to leave.”

In recent years, while the case was hung up in the courts, S.R. was chased by armed gunmen. He became a target because he headed a farmers’ association in one of the resettlement projects near where Dorothy Stang was assassinated. He saw rural workers, friends, and neighbors killed. “My neighbor across the way was murdered. Many died there,” he says, and begins listing the names of seven murdered comrades, one of whom was clubbed to death and another shot to death in his rice own patch. The threats increased every time the workers won a legal battle. To protect themselves, S.R.’s family went to sleeping in the middle of the woods and only going out at night. They could no longer work in the fields they had planted with so much care.

When INCRA finally demarcated the area so these families could live in peace, S.R. sensed that the danger had grown. There was a steady flow of motorcyclists. The grileiros would never accept defeat. Then he asked the program for help leaving his territory for good, but they said that if he left, he would no longer receive protection. He turned to the State Public Prosecutor’s Office, which found an NGO to finance his family’s distant relocation. “How are we going to live now? We finally managed to get some land, where we can’t live now.” Exiled with his family in his own country, the future is uncertain.

The children of Natalha and Erasmo Theofilo, leaders threatened with death in Anapu, watch TikTok videos on the bed in their temporary home in Pará. Photo: Alessandro Falco/Sumaúma

Promises to reform the program

Until the filing of this report, the Pará Department of Justice and Human Rights, responsible for coordinating the state program, had not replied to our questions. SOMECDH, the NGO that has run the program under a contract with the state since 2019, said in an email signed by its president, Joacy Brito, that “the program [in Pará] was inaugurated under a federal administration that unfortunately dismantled, disassembled, and destabilized all previously implemented policies” (a reference to the presidency of Jair Bolsonaro), but even so, the state program remained in place. “Our greatest power lies in coordinating with government agencies so defenders’ needs can be met as quickly as possible,” wrote Brito. “As to improving security in the home of this defender specifically, this is a struggle we are discussing almost every day. We will soon have very solid answers,” he guaranteed. Brito emphasized that the program covers the cost of temporary rentals pursuant to a federal rule and that, when necessary, it also helps with medicine and private health care.

Old photo of an anonymous woman who is in the protection program for human rights defenders and has received threats from a criminal faction; taken in her home in Pará. Photo: Alessandro Falco/Sumaúma

The Ministry of Human Rights and Citizenship, a federal body, informed SUMAÚMA in an email signed by the new coordinator-general of the protection program, Luciana Cristina Furquim Pivato, that it has “structural actions underway” to respond to the program’s challenges. These include setting up a technical work group assigned to outline a proposal for a national protection plan and a draft bill for the program. Once established under a decree law, this would “guarantee the participation of agencies and civil society, with parity and public hearings,” he assured. The ministry further stated that it is reviewing the program parameters set out in an administrative decree from 2018 so it can revise program rules and adjust financial support and other assistance for people in temporary lodgings.

“The coordination office has become aware of some cases involving human rights defenders enrolled in Pará’s protection program. In each situation, we have worked to devise measures to ensure that the reported problems are responded to or resolved,” the coordinator wrote. “In the coming days, we will ask for a meeting with Pará state departments to discuss a plan to address the problems of which we have been made aware.”

Organizations heard by SUMAÚMA, however, were unanimous in asserting that the lives of these defenders will only receive true protection when the government expedites the land demarcation processes that have dragged on for years, thus exacerbating conflicts, and when the people who are threatening these defenders are finally held accountable. “Those who attack human rights defenders enjoy structural impunity. And this is another way of reinforcing violence and curtailing the struggle,” states Alane Luzia da Silva, legal advisor for Terra de Direitos, a human rights NGO that last year compiled a report on the shortcomings of the protection program.

None of the individuals heard by SUMAÚMA have seen their persecutors serve jail time. “The right thing would be to open an investigation and punish the culprits,” says Osvalinda, who estimates she has filed more than thirty police reports pertaining to death threats, bribery, and attempts on her and Daniel’s lives. “Our enemies are fazendeiros, illegal loggers, grileiros, the police, city council members, and the mayor,” she explains.

After spending nearly two and a half years in the temporary house rented by the program, Osvalinda and Daniel could no longer stand living so far from their fields, where their enemies had measured out their graves. “I’m against removing defenders from their land. When you do that, you’re saying that crime is above the law,” she argues. Now, however, she and her husband have had to return to their “temporary shelter,” because Osvalinda needs to have a third cardiac surgery. But, given her place on the waiting list with Brazil’s public healthcare system (SUS), she had to file a lawsuit against the State. Yet another battle for a heart that has always fought hard to keep on beating.

Spell check (Portuguese): Elvira Gago

Translation into Spanish: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Diane Whitty

Photography editing: Marcelo Aguilar, Mariana Greif and Pablo Albarenga

Page setup: Érica Saboya

Erasmo Theofilo, a leader threatened with death in Anapu, looks at drawings his children did on the wall of their temporary home, where they live in exile. Photo: Alessandro Falco / Sumaúma