At noon a loud boom echoed. A violent storm, such as had never been seen in the region, made the sky plummet toward earth. Only a few Xipai survived the unprecedented annihilation, taking refuge under a huge tree that bore all the weight of the sky for an entire day. When night approached, they asked an Armadillo and a Paca to pierce the celestial dome, through to the other side. They widened the holes and climbed up. That’s when the huge tree broke. In the upper world, the surface of the sky turned into the new ground and the spirit Semãwapa went to meet them, gave them seeds so they could plant again, and said they could live there in peace, in their new world. But he warned them: “One day, the sky will fall on you again.”

The Xipai legend called “The falling sky,” still told today by some of our elders, could be a prophecy. The sky, in fact, fell again. It crushed, suffocated, and for years silenced the voices and songs of our people, who at one point were considered extinct. But, just like in our story, an enormous tree stopped the fall yet again. It was Ayumã Xipai. She bore the burden of searching for her people’s place of origin, a land they had one day been forced to flee. The large tree that was Ayumã also fell but left the seeds that are her children and other descendents.

We are Yãkyrixi and Wajã Xipai, her grandchildren, forest-journalists. And now we tell her story.

Yãkyrixi and Wajã Xipai: forest-journalists and the authors of this report, they are both Ayumã’s grandchildren. Photo: Soll/SUMAÚMA

Baú, the first non-home

In the 1930s, the Xipai lived on the left bank of the Curuá River in Pará State, in a village known as Baú. They made their homes there after centuries of persecution by whites as well as by other Indigenous peoples. It was the rubber era, and Baú had become a kind of plantation village inhabited by the Xipai and Kuruaya, who had been enemies in the past, along with the whites who were there to exploit the labor of Indigenous people.

In one of the families there was an Indigenous woman named Miudjã Xipai, who gave birth to three daughters, one of whom was a warrior: Ayumã Xipai. The eldest in a family of women, it was Ayumã’s duty to accompany her father Arikafu, of Kuruaya origin, wherever he went: to harvest Brazil nuts, tap rubber trees, or plant crops. “When we went out to work, we’d close up the house. We’d bed down in the forest,” Ayumã told us. When we were children, our families maintained the old habit from Ayumã’s day of putting a piece of a philodendron leaf in the house to protect it: in empty rooms the plant turns into a snake.

Back then, the villagers in Baú were in constant territorial conflicts with the Kayapó in the region; one day the Kayapó attacked and killed many children and adults. The enemy had greater numbers and forced the villagers to flee. So the Xipai divided up: One group went up the Curuá River, and the other, including Ayumã’s family, went down towards the Iriri.

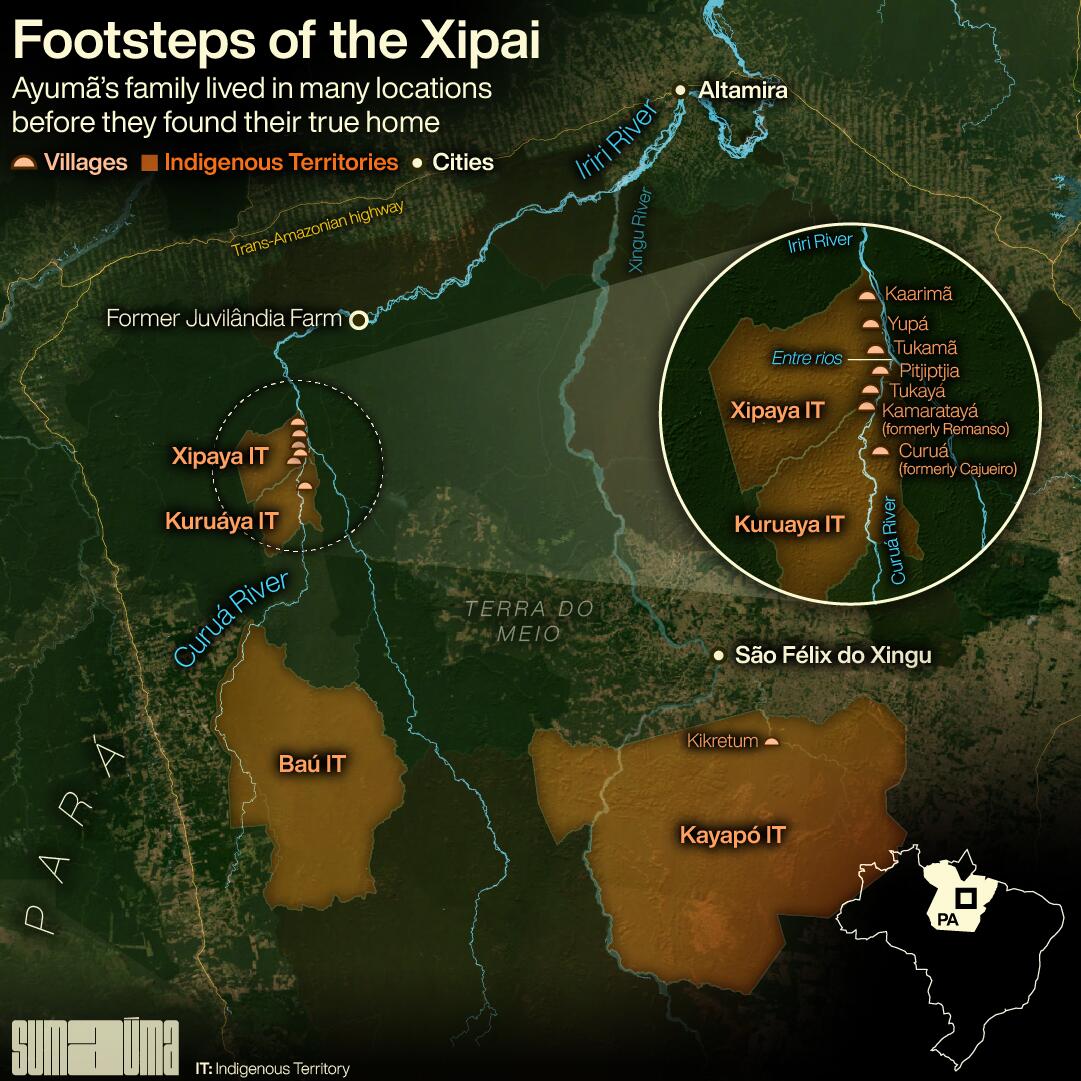

InfogrAPHIC: Rodolfo Almeida/SUMAÚMA

Ayumã was a child. Thinking back on her childhood, she said her family lived off the land for a few years: they planted, harvested, and, soon after, traveled again, out of fear the Kayapó would return. Her father spent whole nights watching over their group, fearing attacks. During this time they grew cassava and, one time, her father spent three whole days making a very large batch of farinha – roasted cassava flour – in advance of their next journey. On the night he finished getting the food ready, the Kayapó arrived at their encampment and destroyed everything.

The small group escaped on a wooden raft to the other side of the river, from where they watched the destruction of their belongings and provisions. When they returned, they saw everything had been destroyed. All of the farinha had been dumped on the ground and the clay pots smashed. The animals they had been raising were dead and the Kayapó had set fire to everything. The Xipai had to continue their journey in search of a place where they could live as a family. Ayumã said her group just wanted some land where they could grow food without anyone persecuting them.

Her life was not easy. She didn’t have a childhood that let her live in peace. She couldn’t let herself get attached to things and had to work hard to help her father.

Colors of Yupá Village: the green of the forest beneath a gray sky and the brown of the thatched house surprised by the yellow of the butterfly. Photo: Wajã Xipai/SUMAÚMA

Then came the whites

The centuries-long war with the Kayapó had forced the Xipai into contact with whites back in the region of Baú village. Arikafu, Ayumã’s father, started working for a man named Antônio Meireles, who was well known in the region. The family was convinced that by working for him, they would be protected from Kayapó attacks. Which is how Arikafu began extracting rubber and trading pelts from the region’s various felines for clothes and food. This forced the family to adapt to non-Indigenous foods, like rice and oil. The boss made himself out to be a friend. Two of Ayumã’s daughters, Yupã (Wajã’s mother) and Kamadï (Yãkyrixi’s mother), say that Meireles’ wife, because she had no daughter of her own, asked Ayumã’s family to let her take Ayumã to the city, promising she’d give the girl a good education. When Ayumã turned 15, she went to live away from her people for the first time in the city of Altamira, which, at the time, was just a handful of streets.

Ayumã left her birthplace, but already knew in her heart that her destiny was to find a home for her family. When she arrived in the city, she saw it was nothing like what they’d promised her. She began working for Meireles’ wife. Ayumã’s job there was to cook and also wash and iron bundles and bundles of dirty clothes. She was paid nothing for her work, and, according to her daughters, ate the family’s leftovers. The young woman’s heart was always troubled, but deep down she was certain she would find her place.

One day, a few months after she had arrived in Altamira, she was washing clothes in the Xingu River when she spotted a young man on a horse. Her heart immediately began to beat harder. Ayumã had never felt that for anyone. The man was Antônio Batista de Carvalho. He was from Altamira, his mother from Ceará, and his father from Sergipe. He was already engaged. Antônio used to say that when he met that “Indian” with long hair, he fell in love on the spot and wanted nothing to do with his engagement, because he was certain Ayumã would be the mother of his children. She fell in love for the first time and had no doubts the young man would be her first love and become her husband. So the two of them ran away. Ayumã went to live with Antônio and his brothers and helped take care of them, since their parents had died.

A few months later, Ayumã became pregnant with a son, and her life slowly began to change. She still lived in Altamira, where her husband was from, but didn’t feel the freedom she wanted for herself and her family. A few years went by, Ayumã had more children, and Antônio decided to sell their place and move to São Félix do Xingu, a neighboring town, with the hope they could better their lives.

Ayumã Xipai and Antônio Batista de Carvalho: the soccer pitch is in front of the house where they lived in Tukamã Village. Photos: personal archives & Wajã Xipai/SUMAÚMA

When the ground disappeared

Life in São Félix do Xingu proved hard. There was a lot of work and little money to support the family, which soon began facing hardship. Antônio worked for the city government, but they couldn’t plant food or fish there, and they had to buy everything they wanted to eat, and they didn’t always have the money.

Sitting in her hammock in a corner of their house, built of old steel oil barrels, a downcast Ayumã had tears streaming down her cheeks. She said to her husband: “My place isn’t here! Our place isn’t here! I come from a land with plenty of food, and I’m not going to die here with my children.” This is how Kamadï Xipai, Ayumã’s daughter, remembers her mother’s words. “It’s my hope that before I die, I’ll find a place we can call home,” Ayumã said. By this time, she’d already given birth to her 24 children.

Antônio asked for help from a friend in the city who was a pilot and willing to try to get the family out of there. This man knew some Kayapó, the long-time enemies of Ayumã’s ancestors, who agreed to host them. Antônio sent a letter asking for help from Coronel Pombo, the leader of Kikretum village, who sent transportation to São Félix do Xingu to fetch Ayumã’s family.

When they arrived at the Kayapó village, however, they were told they could stay there and become part of the village, but on one condition: Ayumã’s daughters would have to marry young men from the village.

Ayumã felt the ground pulled out from under her, because she had nowhere else to go and her family needed a place to stay. She rejected the offer, but her family was allowed to stay on as village workers. The Xipai were responsible for planting some of the village crops but could only keep a little of the food they grew.

Shadow and light: the path from Yupá Village to the edge of the Iriri River. The other side of the river is also forested. Photo: Wajã Xipai/SUMAÚMA

The search for a home

Ayumã dreamt of the land of her ancestors, where she would – truly – be able to live in peace.

Leaving for Altamira as a teenager had not completely cut Ayumã off from her family. Soon after marrying Antônio, she heard her mother Miudjã had died of measles. After she moved to São Félix do Xingu, she received a message that her father Arikafu was coming to the city to visit her, but on the way he tried to stop a fight and was murdered. Without her parents, she started losing touch with her sisters and therefore with all other Xipai she knew.

Yet she didn’t give up trying to find her roots. The search, however, wasn’t easy. She didn’t have a memory of a specific place to go; she only knew her people had lived in the region of the Iriri, Curuá, and Xingu rivers and had vague memories of some of the places she had lived with her parents. Baú Village, where she was born and spent her childhood, now belonged to the Kayapó.

One day, when the family still lived in Kikretum village, she was told by a former coordinator at Brazil’s federal agency of Indigenous affairs, Funai, that some of her people were still living on the Curuá River. The news filled Ayumã with hope, and her family decided to return immediately to their native land.

Ayumã, Antônio, and the 12 children who still lived with them left Kikretum village to look for their roots. First they went to the city of Tucumã, where one of Ayumã’s sons, Wilson Xipai, met a man interested in mining in the Curuá River region. Thinking he would be better received helping a family return than simply showing up with his mining equipment, the man decided to hire a bus to take Ayumã’s family to Altamira, from there they would continue on by boat to their people. After boarding the Mão Divina – Divine Hand – the group traveled for five days in anticipation that they would finally find their place in the world. Ayumã would again be in touch with her mother’s people, for whom she cried so much when thinking back on her childhood.

On January 4, 1991, Ayumã, then just over 50 years old, arrived with her family at the dock in Cajueiro village. They unloaded their belongings, joyful they had finally arrived in the land of their people. But right there at the dock, they received sad news: the village they longed for was not the one they had found. It didn’t belong to the Xipai but to the Kuruaya, the ancestors of Ayumã’s father. As much as she also belonged to his people, Ayumã felt strongly connected to her mother’s family, the Xipai. Her children say she couldn’t hide the heavy blow to her heart when she learned the news.

After the family had gone through this whole ordeal, the head of the local Indigenous agency post offered the family accommodation in one of the agency’s support houses in the region. A few months later, Ayumã and her family still didn’t feel comfortable living with the people in the village, with whom they felt little connection.

So the Xipai decided to move to an area just over half a mile from Cajueiro. They built houses and planted crops. Now it seemed Ayumã’s life was finally better. But Yupã Xipai, one of her daughters, tells how her mother felt at the time: “As much as mother’s life seemed better then, she was still sad not to be among the people she grew up with.”

Ayumã’s life became more enjoyable when she began meeting Kuruaya cousins whose faces she recognized from her childhood. But she still felt something was missing.

Yupã Xipai at Tukamã Village, in front of Middle House, the location for meetings and celebrations, as well as where people gather to make artisanal handicrafts. Photo: Mitã Xipai

Facing down the gunmen

Everyone in the region was aware of the family’s desire to move to the place of their ancestors. The Kuruaya were also fighting for recognition of their land, and the presence of the Xipai could mean dividing the territory between the two peoples, which both wanted to avoid.

One day in mid-1994, a Kuruaya friend of the family told them of a place on the Curuá River, well below the village of Cajueiro, where Xipai Indigenous people once lived. The place, called Remanso, had most recently been the home of Ribeirinhos – members of traditional forest communities – but it had been abandoned. Perhaps this was one of the places where Ayumã had spent her childhood. So the family decided to move there.

They only took what was absolutely necessary to build their new life. But even so, they had to borrow a large canoe from the head of the Indigenous agency post and make four trips, in the middle of the dry season, to bring the whole family, already expanded with grandchildren.

On the banks of the Curuá, a narrow river with crystal-clear waters, they set about building their new home. For days, the men cut timber from the forest and carried it on their shoulders to then transform it into the walls of their houses. Thatch from the region’s babassu palms was used to cover the roofs of the new dwellings, whose walls were sealed with clay. But three months later, Ayumã, her children, daughters-in-law, sons-in-law, and grandchildren were uncertain whether they would live another day.

In October 1994, at the behest of the owner of an old ranch called Juvilândia, gunmen went to Remanso to drive the family off the land. Juvilândia was one of the most scandalous cases of land theft in the region. The ranch covered 3.2 million acres – larger than the state of Connecticut. According to the courts, in 2008 the property represented 34 fraudulent land titles that were later revoked.

At the time, however, the landowner was a powerful man, and his henchmen expelled Ribeirinhos and Indigenous people from their homes with threats of violence and then took possession of the land. The gunmen told them the place where Ayumã’s family lived belonged to their boss and, on his orders, they could murder Ayumã and her children if they didn’t leave immediately. They were faced with a difficult choice: they could leave their people’s ancestral land after so much searching, and thus go on living, or they could stay, which was tantamount to “asking” to be killed. Ayumã and her children decided to defy the men.

The gunmen drew their revolvers. Ayumã and her children took up their bows and arrows. It was a struggle not only for land but for a history, for dignity, and for life. When the gunmen saw the Xipai would not give in, they retreated and returned to the ranch. Ayumã’s family continued to receive death threats but had no one to report them to. When they sought out Indigenous agency officials in the region, they were told Funai couldn’t protect them because it didn’t recognize them as Indigenous. To them, the Xipai were an extinct people.

When she heard this, Ayumã was upset. How could her people be extinct when she was right there?

Ayumã’s family was then told about another place where their ancestors had reportedly lived in the past, called João Martins by non-Indigenous people. Antônio and his children planted some crops there and, within a month, they had already built a new home. On December 24, 1994, Ayumã moved there with almost all of her children – one of whom decided to remain with his family in Remanso, where they continued to receive death threats for many years. But now, Ayumã no longer wanted a temporary home. She decided she would live there forever and fight to turn that place into a village. She wanted to see her people officially recognized by the government.

Sunset: the stream proclaims our arrival at Tukamã village. Photo: Wajã Xipai/SUMAÚMA

Now, finally, a village

Ayumã’s first move was to change the name of the place. São Martins, a reference to a church saint who for years catechized and enslaved Indigenous people in Brazil, became Tukamã, which in Xipai means bow. By early 1995, Tukamã was not just another place to live. It was now the first village to seek official government recognition for the Xipai people.

Ayumã was driven by courage. She was determined not to let a people be suffocated and buried without anyone knowing. But the fight was fraught with difficulty. Because they were not recognized by Funai, the family had no right to health care from the Indigenous Health Support House. The torment of disease, especially malaria, was harrowing, say Ayumã’s children. “As we had no support from Funai or the health service, we suffered a lot,” says Yupã Xipai, one of Ayumã’s daughters, now cacica (chief) of Yupá Village. “We used to get sick a lot and the only medicine was herbal, which our mother made for us. We drank a lot of tea. Nobody died because she took care of us. Mother’s knowledge was very important,” she recalls, with a look of nostalgia.

The lack of official recognition from Funai meant Ayumã and her children made frequent trips to Altamira to demand their rights, but they were always told they weren’t Indigenous and therefore had no rights.

On one of these trips, Ayumã’s son Manoel Xipai, then cacique (chief) of Tukamã village, managed to talk to the Indigenist Missionary Council, which offered to help. The organization sent a representative to Tukamã village to gather some data, which included taking photos and recording interviews with Ayumã and her family.

After the council representative heard Ayumã’s story, he drew up a document, with the help of the Tukamã community, reporting on the existence and presence of the Xipai people in their territory. He then submitted it to Funai. Ayumã was happy someone had finally offered to help her and her children in their struggle. Someone had noticed her efforts to save her people from oblivion. Even so, Funai did not immediately consider Ayumã’s family Indigenous. It took more than a year for that to happen.

This was yet another of the many struggles experienced by Ayumã, a mother who taught her children to persist even in the face of challenges. Though always in the fight, she never let things get her down or failed to pass her knowledge on to her children.

Wearing a blue dress, her hair tied up, her feet crossed, sitting on a small sofa in her living room, her hands stained with annatto and her fingers intertwined, Kamadï Xipai, 43, Ayumã’s youngest daughter, said: “My mother’s life was good, among family. She was a warrior woman who always encouraged us, her children. She was always hard-working and told us about our rights. It was also a tough life because we didn’t have everything. I learned a lot from her. Even in times of difficulty, she was always cheerful, giving us words of comfort and encouragement.”

Ayumã also liked to celebrate with her children. “When the family held rodadas de caxiri [gatherings where people dance and drink caxiri – a traditional drink made from cassava], she’d come and watch. She didn’t like to dance, but she always took part; she’d tell us the story of her father, when she lived with him in the forest and they lived in Baú. She was always beside us, guiding us, telling us about our fight and that it wasn’t going to be easy. But she said we were going to win,” said Kamadï Xipai, clutching the beaded necklace around her neck and smudging it lightly with annatto.

Kamadï Xipai, Ayumã’s daughter: “My mother’s life was a good one. She was a warrior woman, and always encouraged us, her children. And would tell us about our rights.” Photo: Wajã Xipai/SUMAÚMA

After Ayumã’s family fought for official recognition of the existence of the Xipai, relatives from other regions came forward and also declared themselves Xipai. Many of them had not said they were members of this people before or didn’t even claim to be Indigenous, out of fear left by past persecution or shame after suffering the racism of whites for generations.

With the help of the Indigenist Missionary Council, and given Funai’s recognition that Ayumã’s family was truly Indigenous, she and her children began to live out their longed-for dream. But in 1996, when the village was only a year old, they had to be strong once again. They now had to defend their continued presence on their native land.

A landowning company called Rondon Projetos Ecológicos showed up and ordered Ayumã and her family to leave the site, claiming it owned the land. Rondon owned the logging company Incenxil, which claimed to have titles to a farm that later became famous as one of the largest areas of land theft in Brazil. “After we got here, we really established ourselves as the owners of the land. We didn’t accept any kind of threat any more,” said Yupã Xipai. “So we stood up to them,” she said, slamming her hands on the table and raising her voice as she recalled when she had to fight for her land.

Seeing Ayumã and her family would not leave the land Rondon Projetos Ecológicos claimed was theirs, the company opted for a less radical course of action and, strangely enough, the supposed owner of the land decided to help the people of Tukamã village. The company offered to pay each family a salary of 180 reais per month and give them food assistance. After a while, the company realized it wasn’t enough and decided to send even more food. During a Parliamentary inquiry held in 1999 in the Pará State Legislative Assembly to investigate the construction firm CR Almeida, majority shareholder of Rondon, the company said it helped the Xipai maintain the village and that it had a “friendly relationship” with them.

The community accepted the donations because they had a hard time getting food from the city. The food assistance supplemented what they got off the land, such as cassava, yams, and bananas.

Rondon Projetos Ecológicos also started bringing medicine to the village and, since the company’s “generosity” seemed genuine and boundless, it even decided to bring doctors from São Paulo to provide care for Ayumã and her people. The only thing it asked in return was for the families to sign a document. According to company staff, it would prove the village was really using the donated goods.

After a year of coexistence with Ayumã and her village, Rondon Projetos Ecológicos built a base at Entre Rios, the place where the Curuá and Iriri rivers meet, a little over a mile from Tukamã. The coordinator posted there was responsible for holding meetings with the community to inform them of changes requested by his boss and bringing the documents to be signed receiving the company’s “donations”. Although they could all read, Ayumã’s family didn’t fully understand the content of the papers they were signing.

In 1998, two years after Rondon Projetos Ecológicos arrived in the territory, Ayumã and her children heard what they had already suspected from some company staff. The base coordinator and two other employees, a man and a woman, were quitting their positions, but first they wanted to visit Tukamã one last time.

When they arrived in the village, they asked for a meeting, where they revealed the truth about the company. They warned Ayumã and her children not to sign anything else because, without knowing it, they were giving up their land month by month in exchange for food assistance. The former employees also said the community should beware of the new base coordinator, because he was an evil man and would do anything to take the land from the Xipai.

After the arrival of the new coordinator, all “donations” from Rondon Projetos Ecológicos stopped. The company no longer had to hide its claws and fangs. Ayumã’s family went to the base with the intention of driving staff out. However, the new coordinator called in a group of armed men who pointed their guns at Ayumã’s sons and daughters, who were holding babies in their arms. Would taking one step forward mean death? We don’t know. They decided not to take that path, instead retreating to their village to think of another way to get the company off their land.

While they tried to figure out how to get rid of Rondon Projetos Ecológicos, the company banned Ayumã’s family from returning to the base and harassed them in their own village. Men in helicopters flew over their houses, pointing guns at them. Those were terrifying days. Ayumã was afraid of losing her life and even more afraid of losing the lives of her children or grandchildren. But if something happened, she knew she would die with them, because no one there would run from the struggle to protect their ancestral land. Running away isn’t in her people’s blood, in the blood she and her children carry in their veins. Running away wasn’t even an option.

For two years, from 1999 to 2000, the Tukamã village community found a way of dealing with Rondon Projetos Ecológicos. They decided to ask for help from the community’s only supporter, the Indigenist Missionary Council. A representative of the organization went to Tukamã and, working with the community, drew up documents to denounce the company and ask for recognition and designation of Xipaya Territory. The documents were sent to Funai.

After that, the Indigenist Missionary Council offered to take the cacique of Tukamã – who at this point was Luiz Xipai, one of Ayumã’s sons – and other members of the community to Brasilia, where they would attend political movement events. They went to large meetings on the demarcation and ratification of Indigenous lands and other events aimed at making the Xipai people’s territory a reality. In 2004, while all this was going on, Ayumã was diagnosed with diabetes. She was already around 70 years old, and now her health was jeopardized.

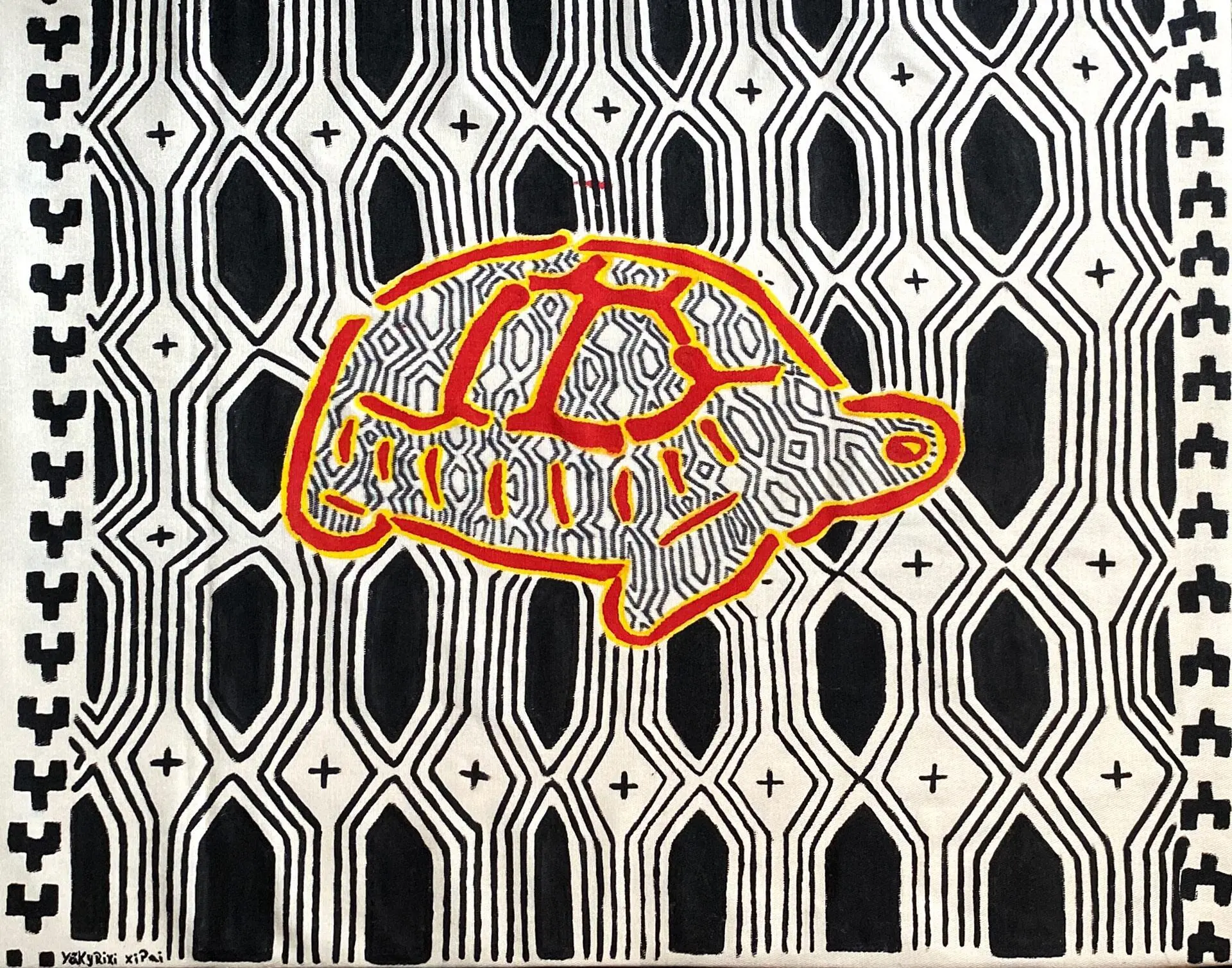

A jabuti tortoise painted on cloth with a bamboo stylus: thïs more-than-human is a symbol of strength and resistance. Art: Yãkyrixi Xipai

Finally, our land

With her hair back, lying in a hammock in a house covered only by thatch and surrounded by chicken wire, 54-year-old Pakuã Xipai adjusts her glasses as she recalls her mother Ayumã’s life after her diagnosis. “She worked a lot in the vegetable garden with dad. They would plant, she’d go into the forest with him to hunt, and she’d be in the day-to-day fight with us, guiding us on what to do,” she said, remembering her mother’s strength.

After the Tukamã community and Indigenist Missionary Council rallied to force Rondon Projetos Ecológicos to leave what would eventually become Xipaya Land, Funai ordered the company out. Rondon was later investigated by the courts. In 2005, Ayumã and her family won another victory: Rondon Projetos Ecológicos left Xipaya Territory.

The first recorded request to Funai for recognition and demarcation of Xipaya territory was made in 1995. It was lodged by the Indigenous Pastoral of the Xingu Prelature, which, in collaboration with the Tukamã village community, drew up documents to send to Funai. They wanted answers as soon as possible because they were worried the land they lived on might suffer further attacks by land grabbers.

In 1996, Funai recognized the Xipai as a non-extinct Indigenous ethnic group. But it was only in 1999 that the agency set up the first Technical Group to carry out studies and surveys to define the Xipaya Indigenous Territory. The work was coordinated by anthropologist Maria Elisa Guedes Vieira, who went into the field in 1999.

In April 2002, Maria Elisa delivered a comprehensive report on the definition and delimitation of the Xipaya Indigenous Territory that proved the historical existence of the Xipai people in the region of the Iriri, Curuá, and Xingu rivers since at least 1750, when Father Roque Hunderfund gave the first accounts of our ancestors. The anthropologist’s document delineated the boundaries of the territory.

Some Xipai later asked that the area proposed by the Technical Group be modified. The Nova Olinda community, made up of some Xipai descendants as well as non-Indigenous people, asked Funai to omit it from the demarcation process.

As a result, in March 2003, Funai asked for a new study to redefine the borders of Xipaya Territory. The anthropologist appointed to carry out the survey was Antônio Pereira Neto, who heard the Tukamã community and Xipai descendants from Nova Olinda in July 2004.

After the anthropological study was done, Antônio Pereira Neto drew up a report confirming the need to redefine the borders of Xipaya Territory. He pointed out that close to the Nova Olinda community there was a location of interest to mining companies where miners had set up camp in the past. The Xipai feared this would hinder the progress of the demarcation process or that, once demarcated, their land would be targeted by illegal miners, setting off clashes. Ayumã always taught her children that mining was wrong and endangered Nature. In the end, Xipaya Territory covered an area of 441,390 acres.

The president of Funai endorsed the anthropologist’s report, and it was published in the federal gazette in 2005. Closing out all the bureaucratic formalities of the demarcation process, the Justice Ministry declared that the Xipai people held permanent ownership of the delimited area in December 2006.

“What a struggle, what a triumph! This shows you will get your land,” Ayumã exclaimed when she heard the demarcation team had begun their work, her daughter Lúcia Xipai recalled. “Today we have a demarcated area, recognized as an Indigenous territory. Never let people humiliate you for what’s yours! I’m very happy because I know that even if I’m not here for long, you’re all together in your own little place. I’m sure you’ll be safe in our land.”

Presidential decree officially recognizing Xipaya Indigenous Territory

The presidential decree ratifying demarcation of the Indigenous Territory, the final step needed to secure the land, was issued on June 5, 2012. It was yet another victory for Ayumã’s family. This family, which had suffered so much in search of their land and the recognition of their identity, now had their territory demarcated and ratified.

Ayumã returned home. She was with her family and had found a new path for the Xipai people.

Midwife to a people

Even in her old age, Ayumã never gave up the habit of waking early and bringing breakfast to her husband in their vegetable gardens. She also enjoyed harvesting crops, as she had always dreamed of having her own space to grow food. Every day, she enjoyed opening the chicken coop and talking to her animals. Her yard was always full of flowers, which she watered in the morning so they wouldn’t die. At noon, Antônio would come in from the gardens and lunch would be ready: fish, sweet potatoes, and roasted cassava flour had to be on the table – they were her favorite foods.

In the afternoon, Ayumã would rest and, around four o’clock, accompany her old man – her affectionate nickname for our grandfather – to the gardens. When evening came, they’d return home and have dinner together. They’d go to bed early after a very tiring day. Before falling asleep, she’d thank Tupã – our God – for the day and the work. This was the life Ayumã had always longed for in her heart.

In 2004, when Ayumã was diagnosed with diabetes, she began going to Altamira quite often for medical care. These trips became more frequent in 2010, but she always returned to Tukamã after a few weeks. In 2011, when Ayumã was 77, her health took a turn for the worse. So she and Antônio moved to Altamira for good, where one of her daughters looked after them until 2014. Even though Ayumã had lived in the city before, she never adjusted to that way of life and would return to Tukamã whenever she could to visit her family.

A year after moving to the city, Ayumã began to feel twinges of pain and traveled to Belém for tests. She discovered she had liver cancer. From then on, her health went steadily downhill. Despite treatment, our grandmother Ayumã Xipai didn’t make it. She died on February 21, 2017, at age 83.

A waxing moon in the Xipaya sky: when a person dies, they go into a deep sleep and transform into Nature. Photo: Wajã Xipai/SUMAÚMA

Ancestral future

Ayumã is gone, but her descendants have taken her story to heart. Her teachings can still be felt in every action in Xipaya Territory. Due to early and forced contact with non-Indigenous people, Ayumã never had the chance to learn her mother’s language. She could only speak a few words, including karaxu (spoon), asa (farinha), kuradada (frog), and a couple of others. She didn’t have time to learn much about her people’s culture. But even so, she didn’t feel any less Xipai and has always encouraged her descendants to revitalize their culture – something her children and grandchildren have done.

When we were children, Yupã Xipai, my mother – Wajã’s mother and Yãkyrixi’s aunt – motivated us to learn the language. She learned it from Xipai elders who had been exposed to the language as children and lived in Altamira. One of Yupã’s sons, Jãdatari Xipai, decided to study it further and today, at the age of 25, he is fluent in the language and is writing a book about it.

In Tukamã village, our cousin Warawara Xipai teaches the younger ones the language that Ayumã dreamed of learning and passing on to her children. Today, I, Yãkyrixi, am pleased when I hear my two-year-old son, Mãzukawa, say iya (water), abi (animal), taeta (to bathe), or sawazi (children) before he’s learned these words in Portuguese. And I know, in the future, he will learn to make the handicrafts I learned from my father.

Today there are six villages in Xipaya Territory, four of them belonging to Ayumã’s family and two to other Xipai family units.

Ayumã’s advice on the territory can still be heard today, but now it’s her children and grandchildren who are repeating it. All the projects developed on our land are designed to protect our home, preserve more-than-humans, and strengthen our culture. Because that was Ayumã’s dream.

Today our grandmother is in a deep sleep, but we see her in every lesson her children pass on to younger generations, in the planting of our gardens, in the stories shared on our doorsteps, or in our caxiri gatherings. And as long as there is a Xipaya Territory and our family lives there, the story of Ayumã will not come to an end.

She now lies in the land she won for her family. She lives in every ebb and flow of the Iriri River, a river she taught her family to respect. She lives in the forest, which she showed her family how to protect. And she lives in the Xipai people, a people she restored.

This is the story of the life of an Indigenous woman. This is the story of Ayumã Xipai, the midwife of our people.

Granddaughters and great-granddaughters in Tukamã Village: “As long as there is a Xipaya Territory and our family remains living there, Ayumã’s story will never end.” Photos: personal archives

Wajã Xipai, 17 years old, is an Indigenous photographer, filmmaker, activist, and forest-journalist with Mycelium-Sumaúma. He is Ayumã’s grandson. He was born and still lives in the territory of the Xipai people, in the village of Yupá, in Terra do Meio, Middle Xingu, Pará, Brazilian Amazon, where he and other youth coordinate the Sekamena network of Xipai communicators, which works to strengthen communication and represent the culture of their people.

Yãkyrixi Xipai, 21 years old, is an Indigenous artisan, nursing assistant in training, forest-journalist with Mycelium-Sumaúma, communicator for the Sekamena network, activist, and Ayumã’s granddaughter. Born on the territory of the Xipai people, in the village of Tukamã, Terra do Meio, Middle Xingu, Pará, Brazilian Amazon, she currently divides her time between her home village and the city of Altamira while finishing her studies. During the forest-journalist co-training program, she realized young people in her community needed to know more about their history in order to strengthen their roots. That’s when she felt the desire to write a feature story about the midwife of her people.

***

The Mycelium-SUMAÚMA Forest-Journalist Co-Training Program began in May 2023. Fourteen young people from the Middle Xingu—four Indigenous youth, three youth from traditional forest communities, one from a Quilombola community, one small-hold farmer, a fisherwoman, an Indigenous health nurse, and young people from urban communities in the city of Altamira—participate in gatherings in the forest and the city. The youth are guided by senior journalists at SUMAÚMA, known as “seed-mentors,” who are in turn guided by the youth, since co-training is an exchange. In this report on the history of the Xipai people, the seed-mentor was Talita Bedinelli.

Coordinated by Raquel Rosenberg, co-founder of Engajamundo, the teaching method used by Mycelium-SUMAÚMA, deliberately eschews any type of orthodoxy. Conceived by Eliane Brum (likewise responsible for supervision and content) and Jonathan Watts, the program maintains the rigor, responsibility, and accuracy of traditional journalism.

Micélio-SUMAÚMA also includes psychoanalyst Ilana Katz, providing care consulting, and producer Thiago de Sousa Leal. Mônica Abdalla is responsible for managing the Program’s finances, with administrative and financial assistant Marina Borges. Micélio-SUMAÚMA receives funding from the Moore Foundation and the Google News Initiative.

Report and text: Yãkyrixi Xipai e Wajã Xipai

Editing: Talita Bedinelli

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Spanish translation: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Maria Jacqueline Evans and Diane Whitty

Infographics: Rodolfo Almeida

Copyediting and finishing: Natália Chagas

Editorial workflow: Viviane Zandonadi

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum