Only the beginning. That is the uncomfortable truth that we cannot escape as we look upon the images of devastation in Rio Grande do Sul.

One of the most intense floods in the country’s history has taken at least 149 lives, forced the evacuation of 538,000 people (including several members and relatives of the SUMAÚMA community) and left about two million without electricity and potable water. Surreal images of roads turned to rivers, football stadiums transformed into lakes, and a horse stranded on a rooftop have upended our expectations of a stable reality. Entire cities seems to be drifting. Certainty appears to have lost its moorings.

In this issue, we include a harrowing opinion piece from Porto Alegre by one of its residents, the biologist and journalist Jaqueline Sordi. She asks why countless warnings have been ignored and explores the futile blame game by politicians who have done little or nothing to address the root cause of the problem. Another native of the region is SUMAÚMA artist, Pablito Aguiar who interviews the residents of his home town, Alvorada, and Canoas and draws pictures of the unimaginably desperate situations that many now find themselves in.

A horse was found stranded on a roof in Canoas, state of Rio Grande do Sul. May, 2024. Photo: Reproduced from ‘Jornal Nacional’/TV Globo

This will not be the last time we witness such scenes in Porto Alegre and elsewhere in Rio Grande do Sul and far beyond. In the past month, we have seen similar destruction in Dubai and Guangdong. Last year, thousands died in flooding in Libya. A few years before that, graveyards in Germany were stripped of their dead by a flash flood. Across the planet, this is an increasingly common story and it will happen again and again, becoming more frequent and more destructive for as long as humanity continues to burn trees, oil, gas and coal. It is these activities that are heating up the planet and destabilising the climate. It is these activities that are supercharging the impact of natural disasters, which are now increasingly man-made.

Of course the Earth has always had rain and floods, but they are growing more intense and frequent. The planet is now between 1.2C and 1.3C warmer than it was before the industrial revolution. That extra heat in the Earth system means the atmosphere can hold an extra 8.4% more moisture than it was able to do 200 years ago. That means more floods and fiercer storms, as well as other types of extreme weather, such as droughts, forest fires and heatwaves.

As SUMAÚMA warned last year, this is a calamity for human and non-human life. Growing food and preventing disease have become more difficult. Last week, the World Meteorological Organization reported tens of thousands of climate-related deaths in Latin America in 2023, at least US$21bn of economic damage and “the greatest caloric loss” of any region.

The ongoing heatwave – and its associated floods and droughts – might once have been dismissed as a rare blip. But once freak events are now becoming more frequent in a world floating on an ever greater wave of climate instability. Professor Jose Marengo, the Director of the Brazil National Center for Monitoring and Early Warning of Natural Disasters, said the old calculations no longer apply: “The tendency of a one-in-a-century-event doesn’t work like before. That’s how we described the Amazon drought of 2005. But then there was another in 2010, and then 2016, and 2023. That’s four one-in-a-century events in less than 20 years.” And this, he warned, is just the beginning.

Aerial view of the city of Beruri, in the state of Amazonas. In September 2023, the region was hit by severe drought and suffered from smoke from illegal deforestation. Photo: Michael Dantas/SUMAÚMA

Climate impacts are accelerating, even as weather systems slow down. A worrying recent phenomenon is that cold and hot fronts are getting stuck, which means more rain or more heat is focussed on one place for a longer time. This increases its destructive power. In the case of Porto Alegre, Marengo said a cold front from the south had combined with strong moisture from the Amazon and then got stuck above the city because a drought in central Brazil “operated like a wall that blocked” the rain system from moving on.

Many of these problems were correctly predicted. At the end of last year, Francisco Eliseu Aquino, a professor of climatology and oceanography at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul said the burning of fossil fuels had created “frightening” dynamics between the poles and the tropics. Cold wet fronts from the Antarctic had interacted with record heat and drought in the Amazon to create unprecedented storms in between.

Last year’s floods in southern Brazil, which killed 54 people in early September and then returned with similarly devastating force in mid-November, were, Aquino warned, a taste of what was to come as the world entered dangerous levels of warming. “From this year onwards, we will understand concretely what it means to flirt with 1.5C [of heating] in the global average temperature and new records for disasters,” he warned presciently.

Yet our industries and politicians continue to make matters worse. While they greenwash their activities with vague promises and weak policies to cut emissions and protect ecosystems, the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is accelerating. March recorded the biggest ever jump in this greenhouse gas, which is warming the planet.

Not surprisingly, global temperatures are also setting unwelcome records. Last month was the hottest April in history. This was the world’s 11th consecutive monthly record – a blistering hot streak driven primarily by human activities, along with the natural El Niño effect. A recent poll of hundreds of climate scientists found most expect global heating to blast past the internationally agreed goal of 1.5C and rise beyond 2.5C, or even 3C. Imagine how much worse floods and droughts will get at this level.

Deforestation makes everything worse. Numerous studies have shown the Amazon rainforest regulates precipitation across a wide area of South America. When trees are cut down or burned, its makes the surrounding area drier and hotter. Science has effectively proved what indigenous people have been saying for centuries: they are part of a forest that holds up the sky.

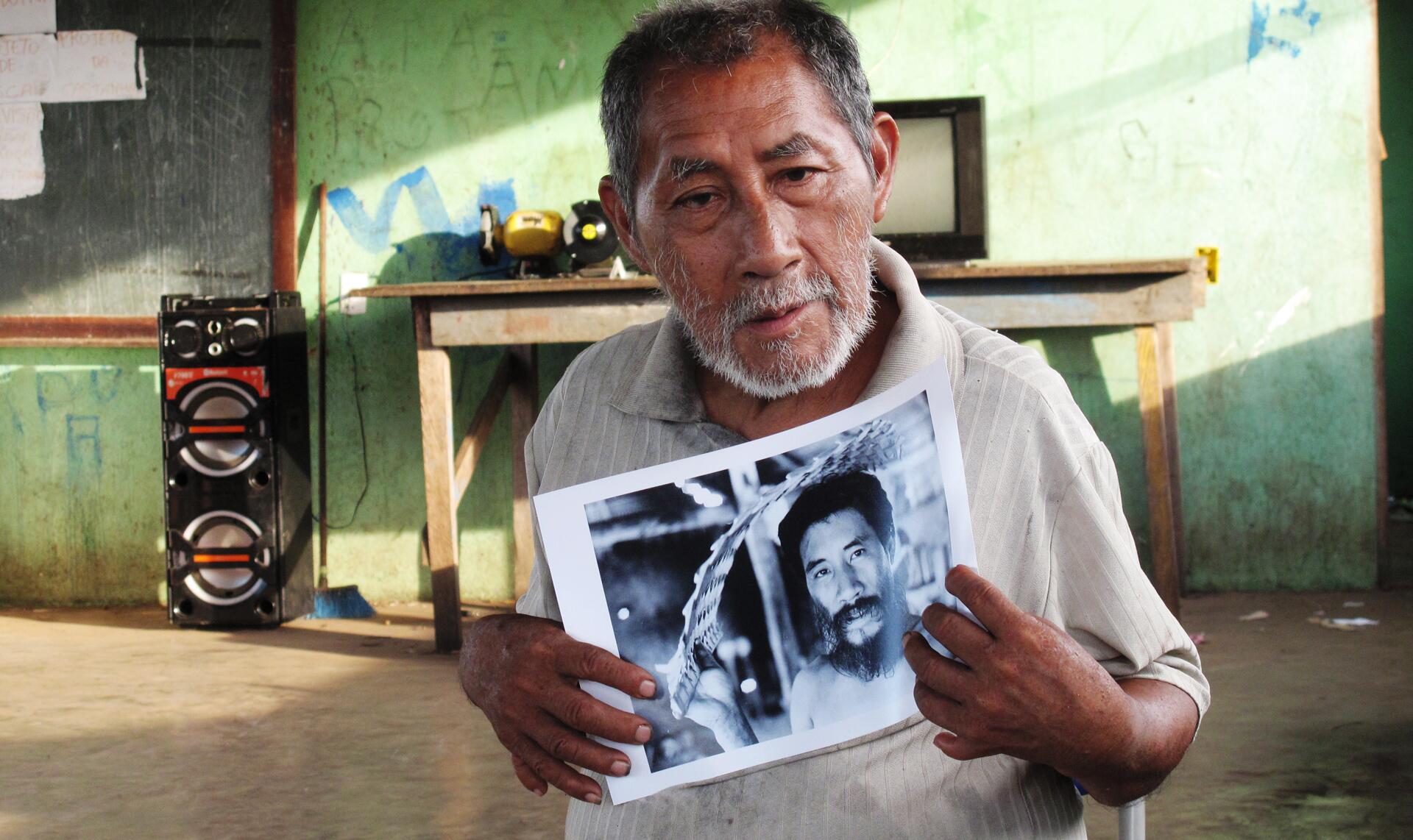

Yet those who forestall climate catastrophe by protecting the forest are constantly under threat. In this issue, SUMAÚMA is releasing unpublished historical records by photographer and anthropologist Milton Guran, who captured the first images of the Arara of Cachoeira Seca, a then isolated Indigenous people living in Pará. In 2018, he returned to their home in the rainforest, where he encountered “an advanced process of ethnocide.”

Tibie Arara, in 2018, holds a photo of himself from 1987 in the Cachoeira Seca Indigenous Land. Photo: Milton Guran

Award-winning reporter Catarina Barbosa contributes a shocking story – with photographer Soll – about the fears of children in the Dorothy Stang Resettlement, in Anapu, where landgrabbers have twice burned down the community school to try to scare residents away.

This is monstrous in and of itself. It is also insane that the government is not looking after those who look after the forest at a time when such pillars of climate stability are needed more than ever. Not enough people are making the connection.

Architects in Porto Alegre are rightly recognising that cities need to be redesigned. The concrete and asphalt laid over practically every inch of soil in urban areas has created death traps because it allows the torrents to flow faster, which makes floods harder to escape, particularly for vulnerable groups like the elderly. City planners are now calling for more open green spaces, more trees and marshes that can absorb the rains. That makes good sense, but why stop there. The same logic that applies to the city applies to the world. The entire planet needs more climate shock absorbers. Forests, oceans, wetlands and other biomes have always soaked up excess. They keep the Earth’s mutability manageable. For that natural technology to function, we must look after the forest and its care takers.

Text: Jonathan Watts

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Portuguese translation: Denise Bobadilha

Spanish translation: Meritxell Almarza

Photo editor: Lela Beltrão

Editorial workflow, copy editing and finishing: Viviane Zandonadi

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum

Six-year-old Ana Clara in the Dorothy Stang resettlement in Anapu. Her school has already been burned down twice. Photo: Soll/SUMAÚMA