1

‘Marina was burned up and turned to smoke’

“Bullets, beatings and bombings,” Evair Vieira de Melo responds to two agribusiness journalists who greet him with a prosaic “good morning.” An agricultural technician affiliated with the Progressive party, he is serving his third term as a federal deputy for the state of Espírito Santo. He is a typical Bolsonaro-supporting politician. He speaks loudly, shooting out disjointed phrases rapid-fire in a defiant tone, and dresses in an unkempt manner. The topic of the conversation is the forest fires devastating the Amazon and the Pantanal, the effects of which had reached São Paulo, putting 48 cities in a state of alert, closing airports and choking Brazil’s wealthiest state with smoke.

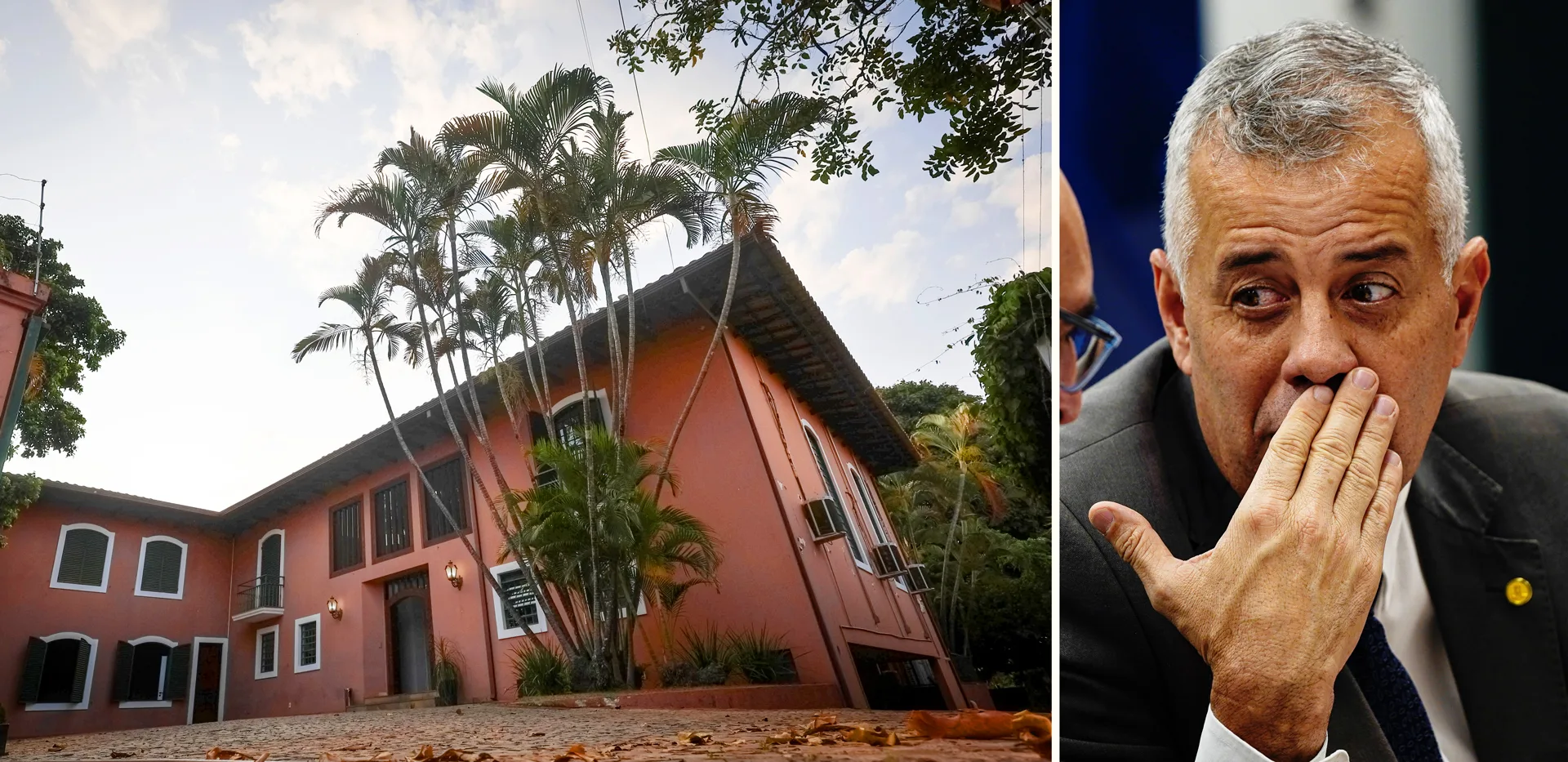

It is late in the morning on Tuesday, August 27, at a colonial-style mansion in Lago Sul, Brasília’s priciest neighborhood. The average income for its residents exceeds R$ 20,000 per month. If it were a municipality, Lago Sul would by far be the richest of the 5,570 in Brazil, according to a study by Fundação Getulio Vargas. The mansion with terracotta walls and large windows behind wooden shutters painted green and surrounded by white trim, is the headquarters of the Agriculture Parliamentary Front and the Pensar Agropecuária Institute. The Agriculture Parliamentary Front, better known as the “ruralist lobby,” is the most numerous and well-organized multi-party front in Brazil’s Congress. This is mostly thanks to the Pensar Agropecuária Institute, a command center bankrolled by 57 business associations that formulates bills and strategies for politicians.

The Pensar Agropecuária Institute’s mansion office, in the extravagant Lago Sul neighborhood, in Brasília, and verbosefederal deputy Evair Vieira de Melo. Photos: SUMAÚMA and Julia Dolce

“The impression is that [Environment and Climate Change Minister] Marina [Silva] was burned up and turned to smoke,” jokes Melo, one of the Agriculture Parliamentary Front’s vice presidents in the Chamber of Deputies, Brazil’s lower house of Congress. The evening before, firefighter Uellinton Lopes dos Santos, 39, had died while fighting a forest fire in the Capoto/Jarina Indigenous Territory, in Mato Grosso. Uellinton was working for Brazil’s environmental agency, Ibama, which is connected to Marina’s ministry. A note of condolence issued by the two agencies explains that his “body was found on Monday morning (August 26), around 1 km from the line of defense against the fire.”

I ask Melo if he can give me an example of any bills against forest fires being backed by the “ruralist lobby.” Seemingly caught off guard, he stutters at first. “And who said… the… the…. Anyone who sets fire to a forest is a criminal, it’s a police matter. This already exists, brother. You have to be nuts to say there’s someone from ag connected to this,” he shoots back, even though I have made no accusations against the powerful economic sector he represents. “The press, Marina Silva, under the Bolsonaro government, [they said] it was all Bolsonaro[‘s fault], [it was] Bolsonaro who set the fire. And now? Are they going to say it’s Bolsonaro again?” he continues, while repeatedly ramming his pointer finger into my chest. “And the fire in California? And the fire in Spain? Have you seen the news out of Australia? New Zealand? They’ve got to stop badmouthing Brazil. We need to make a public policy to pay for a one-way ticket [out of the country] for people who badmouth Brazil.”

Melo and his lobby peers are annoyed because of something Marina Silva had said on Sunday, August 25. While discussing events in São Paulo, Silva said the simultaneous fires were “atypical” and were reminiscent of “fire day.” She is referring to an episode that took place in August 2019, when land-grabbers and ranchers operating along the BR-163 highway, in southeastern Pará, were suspected of starting a series of fires to “grandstand” for then-President Jair Bolsonaro, of the Liberal Party. Despite reiterating that most of the fires began on private property, Marina did not blame agribusiness for the fires in São Paulo, the Pantanal, and the Amazon. Yet the ruralist lobby insists on taking it personally.

Marina Silva (at right) speaks while Lula visits the situation room of environmental agency Ibama’s PrevFogo firefighting program, in Brasília. Photo: Ricardo Stuckert/Press photo

Forming a lobby (or rather, an attempt to influence decisions made by political agents,) is neither illegal nor incompatible with democracy. At Congress, it’s normal to run into lobbyists of all kinds. Public servants using pressure to pass bills beneficial to them; uniformed military police, highway police and civil guards asking for help on issues in their interest; men in ties discretely waiting for a private chat in a congressional office. The ruralist lobby’s difference is its strength, its size, and its structure. For starters, the organizations that make up the Pensar Agropecuária Institute need not even go to the seat of federal government at Praça dos Três Poderes. It is the federal deputies and senators who go to Lago Sul.

The members of the business associations bankrolling the Pensar Agropecuária Institute include major brands like Danone, Kellogg’s and Heineken, large banks like Bradesco, Itaú and Santander, insurers like Porto Seguro and Tokio Marine, and phone company Vivo. Thousands of rural associations, sugar and ethanol plants, industries of all kinds, law firms, and finance sector companies make up the 57 organizations supporting the Pensar Agropecuária Institute. Some companies, like agrochemicals manufacturers Bayer, Basf and Syngenta, US-based food multinationals Bunge and Cargill, Brazilian multinationals BRF and JBS, and Swiss-based Nestlé, are members not of one, but of various industry trade groups. Each organization (see a full list in the infographic below) contributes a monthly fee to defray the costs of renting the mansion and paying the Institute’s employees – 30, according to its official website. The amount contributed is confidential, but sources put it somewhere around R$ 14,000 to R$ 20,000 per month. A conservative estimate, using the low-end figure, gives the organization a monthly budget of some R$ 800,000.

Many of the brands whose trade associations form the Pensar Agropecuária Institute assure their consumers they are committed to conserving the environment. Yet in the Lago Sul mansion office, their industry trade groups are working to craft bills that do exactly the opposite. A law easing restrictions on agrochemicals, one imposing a historic cut-off point for demarcation of Indigenous Territories, proposals to slash the size of legally-mandated reserve areas on Amazonian farms, efforts to choke funding for Ibama (the Environment Protection agency), relaxing environmental licensing rules, or hindering the creation of new environmental conservation units are just a few examples. As Marcio Astrini, the executive secretary at the Climate Observatory, said, the mansion serves as “the center of legislative production for environmental regression.” And its operators prefer to work far from public scrutiny.

Tuesdays are the busiest day at the Pensar Agropecuária Institute. It’s the day when its president, Nilson Leitão, a former federal deputy for Mato Grosso who is affiliated with the Social Democratic Party, welcomes congressional ruralist lobby leaders to set priorities and strategies for the week. Lunch is served to the lobbyists and members of Congress (the day’s menu features grilled chicken breast, steak, rice, cassava pirão, and salad), who gather around a rectangular table in the Homero Pereira Room, thus named in honor of the politician from Mato Grosso who was part of the institute’s foundation and who wrote the bill for the historic cut-off point for demarcation of Indigenous Territories. Homero Pereira died in 2013, at 58 years old, the victim of cancer.

Everything happens behind closed doors. Journalists are confined to a press room decorated with two leather couches and two coffee tables pushed against a wall. On top of them, publications lauding the sector are offered to pass the time – one is dedicated to “social and environmental responsibility” in the tobacco industry. Next to the entrance is a banner with the Parliamentary Agricultural Front logo – identical to the Pensar Agropecuária Institute logo. In front of it, on a platform, are three microphones. They are from the Canal Rural network, (which belongs to J&F, a company owned by the brothers Joesley and Wesley Batista who founded the JBS meat conglomerate); from the Canal Agro+ network, (the result of a partnership between the Band Group, the Pensar Agropecuária Institute, and the Confederation of Agriculture and Livestock); and from the Canal do Boi network, (founded by a rancher from Campo Grande in the 1990s to broadcast animal auctions and which claims to be the “world’s first agribusiness broadcaster”). Except today the only speech to the press will be a brief and muddled statement from Evair de Melo. SUMAÚMA’s questions for the deputy had been quick to reach the Pensar Agropecuária Institute’s Communications department, which decided to cancel the press conference normally given by the Agriculture Parliamentary Front’s president, Pedro Lupion, a federal deputy representing Pará for the Progressive Party.

Microphones waiting for an interview at the Pensar Agropecuária Institute’s mansion, but only for people who won’t ask tough questions. Photo: Julia Dolce

From the press room, the only view to the inside of the mansion is blocked by a door, guarded by an employee from the Pensar Agropecuária Institute’s Communications area. As soon as the deputies and besuited people come to the door, it is quickly opened and closed. The doorknob invariably falls off and needs to be put back in place. Out on the mansion patio, I see a woman walking around wearing a CropLife Brasil badge – an association of agrochemical manufacturers. I introduce myself and ask for an interview. She apologizes and says she can’t talk, but she’s sure the Pensar Agropecuária Institute will be glad to answer my questions. In the meantime, journalist Julia Dolce, who is also at the mansion, took some pictures of the nameplates of some of the entities whose representatives had taken part in that Tuesday’s luncheon. An institute employee immediately approaches her and asks that she delete the photos. As an executive at one of the organizations that makes up the Pensar Agropecuária Institute would tell me days later, none of this is casual.

I go to the gate and ask to speak with the head of the Pensar Agropecuária Institute and Agriculture Parliamentary Front Communications department, Danielle Arouche. While I wait, a short fellow wearing slacks and a white dress shirt walks by me and says: “Journalists really are scum.” When I am finally allowed to go in and speak with Arouche, the man is sitting next to her at a meeting table. His name is Ibiapaba Netto and he made his career as a journalist with outlets like O Estado de S.Paulo and Istoé Dinheiro Rural before moving on to work as a communications adviser for large economic groups. Since 2013, he has been the executive director at CitrusBR, an organization representing citrus juice exporters. He also coordinated the Communications and International Relations commissions at the Pensar Agropecuária Institute – according to his LinkedIn profile, he currently heads the Labor Commission.

Contrary to the CropLife Brasil representative’s prediction, the communications boss informs me that none of the questions sent to the Pensar Agropecuária Institute will be answered. “The institute only dialogs with the sector. It’s the Agriculture Parliamentary Front that talks to society,” she says by way of justification. Yet Pedro Lupion would also not agree to speak with me. That was why I had sent him some questions by e-mail on August 23 – one month later, I still hadn’t received a response. My questions, say Danielle Arouche and Ibiapaba Netto, are “biased.”

SUMAÚMA’s interest in profiling the Pensar Agropecuária Institute seems to have triggered a gag response. Someone with access to the Institute’s goings-on said the communications staff had tried to find out who was giving me information. None of the politicians with the front answered SUMAÚMA’s requests for interviews. Not even the other Agriculture Parliamentary Front vice president in Congress’s lower house, Arnaldo Jardim, representing São Paulo for the Cidadania party, would grant an interview. A politician seen as moderate and polite, he is connected to the country’s vice president, Geraldo Alckmin. Questions were also sent to Zequinha Marinho (Podemos party, representing Pará, and the senate vice president) and federal deputies Marussa Boldrin (Brazilian Democratic Movement, representing Goiás, and the Central-West region vice president), José Rocha (Union party, representing Bahia, and the Northeast region vice president), Domingos Sávio (Liberal Party, representing Minas Gerais, and the Southeast region vice president), and Luiz Nishimori (Social Democratic Party, representing Paraná, and the South region vice president). Vicentinho Júnior (Progressives Party, representing Tocantins) is listed on the Agriculture Parliamentary Front website as the North region vice president, but he took a leave from his position as a federal deputy to take over a cabinet position in his state.

By the end of that Tuesday, the Agriculture Parliamentary Front had issued a press release. Because the fires that have for years destroyed the native vegetation of the Amazon, the Pantanal, and the Cerrado are now causing São Paulo’s agribusinesses to incur losses, the text announces “coordinated action to approve bills to stiffen punishments for crimes of arson.”

Nilson Leitão, the Pensar Agropecuária Institute president. At right, Brasília is covered by smoke from forest fires in mid-September. Photos: Luis Macedo/Chamber of Deputies and Evaristo Sa/AP

2

‘Don’t embarrass my lobby’

After ten tries, in September 2009 the ruralist lobby managed to form a special commission to debate a new Forest Code. The law in effect at the time dated back to 1965. Or rather, back to the business-military dictatorship that oppressed Brazil from 1964 to 1985, encouraging the Cerrado’s destruction for pasturelands and soybean monocultures and executing a series of colonization projects that sparked the Amazon’s devastation. With the country’s re-democratization, starting in the late 1980s the law was strengthened by successive elected governments, which were pressed to pay some attention to the environment. When the environment minister at the time, Carlos Minc, established a fine, starting in December 2009, for farm-owners who failed to comply with the legal reserve area (whereby protected forest area should cover 20% to 80% of a property, depending on the biome), the ruralists raised a fuss and were able to control the issue.

Moacir Micheletto, a federal deputy representing Paraná for the Brazilian Democratic Movement, was appointed to chair the commission. He died in 2012 in a car accident and was one of the ruralist lobby’s most radical politicians. Micheletto and two equally intransigent colleagues – Homero Pereira and Luis Carlos Heinze, the latter currently a senator representing Rio Grande do Sul for the Progressive Party – had been demanding support from organizations representing the agribusiness economy. It may seem strange now, but at the time “industry trade agents did not have a reasonable number of demands, narratives to defend them, and strategies to implement them,” notes anthropologist Caio Pompeia in his book on agribusiness policy, Formação Política do Agronegócio (Editora Elefante, 2021).

Micheletto had introduced a bill to change the Forest Code back in 1999, but it failed. For this new opportunity not to be wasted, something had to change. With the encouragement of this trio of politicians, two regional ag sector organizations – the Mato Grosso Association of Cotton Producers and the Association of Soybean and Corn Producers of Mato Grosso – agreed to take money from their pockets and fund an office to support the ruralist lobby. “It was the embryo of the Pensar Agropecuária Institute, which would revolutionize the field,” writes Pompeia, who has spent over 10 years researching the political influence of the rural sector.

A fundamental figure emerges at this point: João Henrique Hummel Vieira. One of today’s best-known lobbyists in Brasília, he had been providing consulting services to the Association of Soybean and Corn Producers of Mato Grosso since 2005. In 2008, he had helped to overhaul the Agriculture Parliamentary Front. Now, he had the chance to deliver a forest act to his clients’ liking. He knew it would not be easy. Different from now, there were none of the “secret budget” pork barrel projects or parliamentary amendments with mandatory payments. The majority of congressional members therefore tended to vote with the government so they could, in return, ask for funds and projects for their voting bases.

João Henrique Hummel, the man responsible for assembling and consolidating the powerful agribusiness lobby. Photo: Pablo Valadares/Chamber of Deputies

To win the tug-of-war with the environment minister serving under Lula, who was extremely popular at the time, Hummel knew he would need a bold strategy. The first task was to win over the rapporteur, that is, the politician on the commission who would draft the new law’s text. That was Aldo Rebelo, at the time a federal deputy representing São Paulo for the Communist Party of Brazil (he has now switched to the rightwing Brazilian Democratic Movement party and has served as a secretary under São Paulo’s former mayor Ricardo Nunes, his party colleague and a Bolsonaro backer. “When Aldo was chosen, the parties on the left thought he might even be a middle ground guy,” recalls Suely Araújo, a public policy coordinator at the Climate Observatory and formerly the head of Brazil’s environmental agency, Ibama, during the Michel Temer administration (2016-2019). At the time, she was a legislative consultant in the Chamber of Deputies and was keeping close tabs on everything.

The Pensar Agropecuária Institute would only be formally founded in 2011, but Hummel began to gather his assault force of congressional members and advisers at a traditional bakery café in the Lago Sul neighborhood. They realized that winning the war of narratives was crucial – not just outside of Congress, but inside as well. Because federal deputies seldom have a thorough understanding of the issues they will vote on, they created an embryonic advisory structure capable of arming parliamentarians with ample, direct, and easily-understandable arguments. Not much help is found from office advisers, the party, or Chamber consultants. Yet the Agricultural Parliamentary Front would be prepared to deliver content and political strategies to whoever wanted to show up to the debate.

The report Rebelo submitted in June 2010 already contained the following epigraph: “Dedicated to Brazilian farmers.” The word “farmers,” associated with people who put food on Brazilian tables, covers up the fact that the change to the law mostly benefited those with large landholdings, rural beef company owners, and large-scale producers of soybeans used to feed pigs and chickens on other continents. It exempted farmers from restoring legal reserve areas that had been destroyed and properties measuring up to “four rural modules” – a measure equal to 100 hectares in some of the Amazon – from having to keep a single tree standing. The discovery that an attorney providing legal advice to the Agriculture Parliamentary Front had written at least part of the text did not change the law’s trajectory. The battle was lost.

Soybean monoculture in Santarém, Pará, near the edges of the Planalto Santareno Indigenous Territory, of the Apiaká and Munduruku peoples. Photo: Michael Dantas/SUMAÚMA

The text was put to a vote in 2011 – when Dilma Rousseff (Workers’ Party) was now president and Michel Temer (Brazilian Democratic Movement) was vice president. It was up to Henrique Eduardo Alves, a federal deputy from Rio Grande do Norte, to make it clear that the Forest Code had profoundly shifted the relationship between the Executive and Legislative branches. Alves was the Brazilian Democratic Movement leader in the lower house, but from the floor of congress, and before a full session, he sent a message to the ministers affiliated with his party: “Don’t embarrass my lobby, because it will be of absolutely no use. Now is the time for this house to affirm itself. This here is a branch of government,” he cried, celebrating “the victory of Brazilian agriculture and production.”

In the Senate, the government would be able to soften some of the blows it took in the Chamber of Deputies. “But the legislation became more flexible. Today’s Forest Code is less strict, in certain provisions, than the last one,” says Suely Araújo. Politically, it would all be different from there on out. The Agriculture Parliamentary Front had become the strongest lobby in Congress. The Pensar Agropecuária Institute would attract successive industry trade organizations, delighted by the strength shown by the new model of lobbying. To observers, Hummel was able to anticipate the current political moment, where a Congress with hypertrophied power is able to impose a series of government defeats. Sought for comment, the lobbyist declined to be interviewed for this story. He had initially agreed and proposed scheduling a time. Later, he stopped answering calls and responding to messages sent to his cell phone.

Today, it is almost impossible to walk through the rooms where congressional commissions meet to debate topics in the interest of agribusiness without running into advisers carrying cardboard files emblazoned with the Agriculture Parliamentary Front and Pensar Agropecuária Institute logos. Inside of them is the position – opposed or in favor – and arguments formulated at the Lago Sul mansion for the issues of the day. Each politician in the front receives theirs before the meetings start. Congress members who get bills tossed and the narratives along the lines of “anyone who’s anti-agriculture is anti-Brazil” are broadcast across social media and cable and internet networks connected to agribusiness. This work is done by a team of 11 people (more than one-third of the entire Pensar Agropecuária Institute staff) who focus solely on communications tasks, like producing videos, notes and social media content, feeding the in-house news site (Agência FPA), and even publishing a magazine every two years.

Henrique Eduardo Alves and Michel Temer at an event after Dilma Rousseff’s impeachment, in May 2016. Photo: Ricardo Botelho/Brazil Photo Press via AFP

3

The punk rock lobbyist

A close aide to João Hummel usually describes him as “the punk rock lobbyist.” It is because of his love of confrontation. When at the Congress building, he acts as if he were in his own home. At a special Chamber of Deputies commission that discussed the Poison Bill from 2016 to 2018, he liked to sit in the front row, among his ruralist colleagues. The bill, aimed at making it easier to register and sell agrochemicals, was passed in 2023, after over 20 years of discussions. He was once caught raising his hand to vote, as if he were a member of Congress. At the same commission, he at one point laughed at then-federal deputy Alessandro Molon (representing Rio de Janeiro for the Brazilian Socialist Party), who had criticized the bill because it allowed substances to be registered that were suspected of causing cancer in children and adults as well as fetal malformations. “What are you laughing at, sir? We’re talking about people’s lives,” the Brazilian Socialist Party politician said, reacting.

“Everything causes cancer. Dust, car exhaust. So what? Are you going to stop riding in cars?” Hummel said mockingly in an interview with Agência Pública in 2018, when asked about the bill. The lobbyist likes to tell those close to him that “every relevant thing the ruralist lobby introduced over the last 15 years” is his work – including the Poison Bill. Whatever the case, his style is inseparable from the growth and consolidation of the Pensar Agropecuária Institute – where he was the executive director from the time it was founded in 2011 up to 2021.

To handle the demands of the 57 current organizations, the Pensar Agropecuária Institute is built on thematic commissions. The communications adviser refused to say which commissions there are and who are their members. In 2019, when anthropologist Caio Pompeia was authorized to carry out research at the Institute’s headquarters, there were over ten, including “Property Rights,” “Field Security,” “Rural Indebtedness,” and “Food and Health.”

One Pensar Agropecuária Institute employee and one consultant are appointed by the various organizations to each commission. It is these “specialized technical agents [that] elaborate, in dialog with the associations, draft bills and constitutional amendments,” Pompeia says. “The commissions are rounded out with the participation of a member of Congress, the same member designated as responsible for the commission of the same name at the Agriculture Parliamentary Front’s director’s table. Although the front does not present itself like this, in most cases the Pensar Agropecuária Institute and Agriculture Parliamentary Front commissions are indeed a common space for private-congressional articulation.”

While investigating this story, lobbyist Alinne Christoffoli was one of the few people who agreed to speak openly about the Pensar Agropecuária Institute. When we talked in late 2023, she was working for the Brazilian Association of Soybean Growers in Brasília – she is currently residing in Belgium. “I’ve worked as a lobbyist for 17 years, I don’t have any problem saying that,” she told me at the time. She then provided some details on the inner workings of the Pensar Agropecuária Institute. “The [legislative] demand comes from us, the organizations. For example: the Brazilian Association of Soybean Growers is interested in improving the agricultural planting calendar. First, a consensus needs to be reached, between 30, 40 organizations, on the technical commissions,” she said.

The role of the commissions is precisely to build consensus among the industry organizations. It is there, and not under the public’s watch, that heated discussions are held, and whoever is more convincing – or stronger – wins. Once consensus is reached, it is brought to Pensar Agropecuária Institute president Nilson Leitão. And it only reaches congressional members afterward. “When everyone sits down to lunch, the [consensus on the] primary agenda has already been reached, decided on by the Pensar Agropecuária Institute and parliamentarians,” says Christoffoli. Of course, it is not a one-way street. The politicians also bring issues related to their voting bases to the Pensar Agropecuária Institute. And every now and again they happen to disagree with what the business associations want.

Meating of the Agriculture Parliamentary Front, in Brasília. Sitting at the table, from left to right, are Evair de Melo (PP-ES), Tereza Cristina (PP-MS), Pedro Lupion (PP-PR), Sergio Souza, (MDB-PR), Zequinha Marinho (Podemos-PA), and Rafael Prudente (MDB-DF). Foto: Renato Araujo/Chamber of Deputies

A skilled negotiator, João Henrique Hummel was usually crucial in stitching together consensus among the associations as well as between them and the politicians. However, he left the Pensar Agropecuária Institute in 2021, following misunderstandings with Nilson Leitão. He took part of the team with him and set up his own lobbying firm, while also working on two other parliamentary fronts: Entrepreneurship and Biodiesel. Since then, the Entrepreneurship front has also begun to hold weekly luncheons in Brasília – also on Tuesday.

Leitão, on the other hand, is regarded with some reservation by congressional members precisely because he is also a politician. The institute has, for observers, lost some of its capacity to drive the debate in Congress. The ruralist lobby turned aggressive in its opposition to Lula, while part of the organizations under the Pensar Agropecuária Institute umbrella would like to have a friendlier relationship with the government. The president of one of these associations nevertheless disagrees. “Hummel is an amazing articulator, but even for him it was tough to manage the interests of nearly 60 associations. And the decision to be reactive to the government came from the Agriculture Parliamentary Front itself. Not even Hummel would be able to change this,” he said, asking for anonymity.

The far-right’s rise has made some positions explicit. Two directors of the Association of Soybean and Corn Producers of Mato Grosso in Brasília, the entity that began the movement that resulted in the Pensar Agropecuária Institute’s creation, were investigated by the Mixed Parliamentary Inquiry Commission for the attempted overthrow of the government on January 8, 2023: Antonio Galvan, its president from 2018 to 2020, and Lucas Costa Beber, vice president from 2021 to 2023. The Commission’s final report asked that both be indicted. Beber was nevertheless elected president of the organization for the 2024-2026 period.

“Many of these organizations became highly politicized. Talking about the environment turned into a Communist thing, something imposed from outside to block Brazil’s development. This is very prevalent, especially in border regions, which see agriculture as the only chance they’ll have,” says an executive at one of the few associations that is part of the Pensar Agropecuária Institute and has tried – out of commercial interest, but unsuccessfully – to modernize the industry’s view of issues like the climate and environmental conservation.

The Agriculture Parliamentary Front’s current president, Pedro Lupion, defends Jair Bolsonaro and says he will work to give him amnesty so he can run for president in 2026. Among the front’s members are some of the loudest names serving in Congress on the extreme-right – like Evair de Melo. Whether this actually bothers the Pensar Agropecuária Institute’s member organizations is, however, unclear. After all, the Agriculture Parliamentary Front continues to deliver results for its members: it guaranteed discounted taxes on agrochemical purchases, it kept ultraprocessed foods off the list of products that will have to pay the Selective Tax (referred to as the “sin tax”) under the latest tax reform, and it ensured meat was included as a tax-exempt basic staple. The last two items are awaiting ratification by the Senate.

Cattle on pastureland in the Amazon; at right, a lonely Chestnut Tree on devastated land. Photos: Lela Beltrão/SUMAÚMA and Pablo Albarenga/SUMAÚMA

4

‘Nobody wants Indians invading land’

After its Forest Code victory, the Pensar Agropecuária Institute turned its attention back to Indigenous Territories. The continued demarcation of Raposa Serra do Sol, in Roraima (home to the Ingarikó, Macuxi, Patamona, Taurepang and Wapichana peoples), following a lengthy trial in the Federal Supreme Court, put large landowners and corporations on a state of alert.

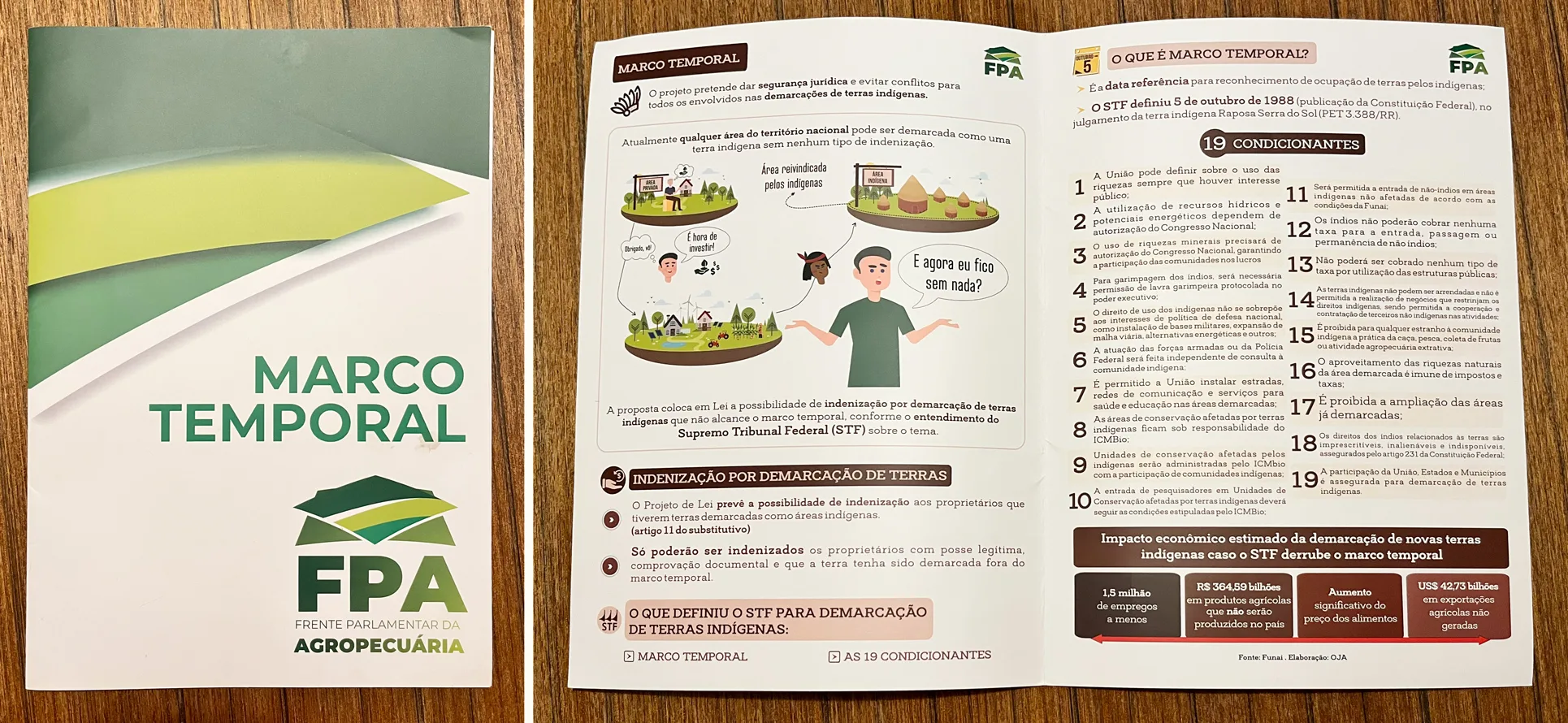

The Pensar Agropecuária Institute’s member association made the issue one of their primary agendas. In documents given to the presidential candidates in 2014, the Brazilian Association of Agribusiness asked for “a new regulatory framework for demarcations of Indigenous Territories, through constitutional amendment.” The Confederation of Agriculture and Livestock in turn said that it was “urgent and definitive to cease demarcation actions and the government should adopt mechanisms to acquire land in compliance with any demand for new areas for the communities.”

Lobbyist Alinne Christoffoli, who worked for the Association of Soybean and Corn Producers at the Pensar Agropecuária Institute, said that “all the organizations wanted” the historic cut-off point to only allow for demarcation of territories that the Indigenous people were occupying on October 5, 1988, the date when the current Constitution was enacted. “We made demands of them [the members of Congress]. Demarcation of Indigenous Territory is a priority issue for the entire [agribusiness] chain. It’s not just for rural producers, no. Or else the pulp and paper companies, the forest guys, wouldn’t be there. Because they don’t want to be invaded either. Nobody wants a land invasion, not even by the Landless Workers’ Movement, not by Indians, not by Quilombolas. Legal insecurity, right? In Brazil, there’s already too much.”

In mid-2023, the Federal Supreme Court was about to resume hearings on the constitutionality of the historic cut-off point. It was a matter of weeks before the Agricultural Parliamentary Front mowed it all down. One of its members, federal deputy Arthur Oliveira Maia, representing Bahia for the União Brasil party, brought back a bill introduced by Homero Pereira in 2007 and produced what the Indigenous Movement would call the “Apocalypse Bill.” With the blessing of lower house president Arthur Lira, representing Alagoas for the Progressives Party, the bill was passed under an emergency regime. Days after the Supreme Court had already ruled the historic cut-off point unconstitutional, it was also passed by the Senate.

In those weeks, the front’s advisers scurried about with files produced just for that vote, showing how important the issue was for the lobbyists at the Lago Sul mansion. Inside the files was a cartoon of a small family farmer, expropriated by an Indigenous person from the land he inherited from his grandfather. “And now I get nothing?” the young man asks. A sheet with arguments to be used in any debates lists debating points such as “the need to ensure peace and tranquility in relation to the country’s lands” and it says that “Brazil’s Indigenous Territories represent the total area of France, Spain, Switzerland, Portugal and Austria.” It fails to mention that all of the country’s territory belonged to the Indigenous people prior to its invasion by Europeans in 1500.

The folder with content advocating for the historic cut-off point was produced by the Institute and distributed to the Front’s politicians in Congress. Photos: Rafael Moro Martins/SUMAÚMA

Indigenous Territories currently occupy less than 14% of Brazilian territory – a total of 117 million hectares. For the sake of comparison, soybean monocultures covered nearly 46 million hectares in the 2023-24 harvest – one and a half times the size of Italy. Indigenous Territories play a crucial role in preserving Nature: according to MapBiomas, they lost just 1% of primary vegetation from 1985 to 2023. In that same period, private land – like large soybean landholdings – lost 20% of their forest cover.

The ruralists continue to apply pressure on this issue. So much so that the Supreme Court declined to confirm what had already been decided regarding the historic cut-off point: by order of Justice Gilmar Mendes, a “reconciliation” commission was formed on the topic. At the second meeting, the Alliance of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil walked away from the table. Mendes, who has ties to ruralism, ordered the “reconciliation” to proceed regardless.

Arthur Maia (União-BA) and Arthur Lira (PP-AL): using the Front to mow down Indigenous rights. Photos: Vinicius Loures/Chamber of Deputies, YouTube screenshot, and Pablo Valadares/Chamber of Deputies

5

Fire! Fire!

Wednesday, September 4. For another morning Brasília is waking up under a blanket of smoke from the fires destroying the Amazon, the Pantanal, and the Cerrado, Environment Minister Marina Silva is sitting at the head table during a meeting of the Senate Environment Commission. She was invited to talk about the fires. “Since I was a senator, I have been saying this would happen,” the minister says, kicking off her speech. She then goes through the horrifying data: although 27% of the areas burned in the Amazon are used for agricultural activities, 32% were covered by primary vegetation. “It means we are in a severe climate change process, with the forest in the process of losing moisture,” she instructively explains. Nobody seems to hear her.

The first senator to speak, Rosana Martinelli, representing Mato Grosso for the Liberal Party, wants to know if the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples “is raising awareness among our Indians (sic) to not set fire to their areas.” Because “it’s a cultural issue.” She is with the ruralist lobby, for whom the Indigenous people will always be a convenient scapegoat. She is also being investigated in an inquiry opened by the Federal Supreme Court into the January 8 attacks to overthrow the government. Senator Martinelli was formerly the mayor of Sinop, a city in the state’s north that was also previously led by the Pensar Agropecuária Institute’s Nilson Leitão.

“[The Ministry of Indigenous Peoples] is doing a lot,” Marina responds. “Firstly, because it’s the ministry of a people who have never deforested – an unimaginably large contribution. The best firefighters are the Indigenous people. They know how to work during the night, they are able to withstand the high temperatures and low humidity. We can [create] a program to educate non-Indigenous people, to not use fire the way they are using it. They [the Indigenous people] need to educate us.”

Jaime Bagattoli, a senator from Rondônia for the Liberal Party, raises a peculiar solution: reward the invaders, deforest, and then set fire to public land, opening up new pasturelands. “We’re going to solve the deforestation problem when we give [land] titles to the producers,” he argues Bagattoli was born in the interior of Santa Catarina and, in 1974, he “came to Rondônia to explore the country’s North region.” He took part in what British documentary maker Adrian Cowell, who spent ten years in the region, called “The Decade of Destruction.” Rondônia is the most deforested state in the Amazon – 40% of its forest cover has already been turned to timber or gone up in smoke. “The people behind this [the fires] have an interest,” Marina reacts. “They start fires, then they spread seeds for pasture, and later [the Senate] comes asking to regularize land that was criminally destroyed. It is theft of public property,” she says, exasperated.

Rosana Martinelli (PL-MT) and Jaime Bagattoli (PL-RO), the voices of landholders at a Senate hearing with Marina Silva. Photos: Bruno Spada and Will Shutter/Chamber of Deputies

The session drags on with repeated attempts to exempt agribusiness from any guilt for the fires and to embarrass the environment minister and few expressions of an understanding of the complexity and severity of the problem. At the end, the commission president, Leila Barros (Democratic Labor Party), a former volleyball player who medaled at the Olympics and Pan-American games and was elected to the Senate to represent the Federal District, is overcome with emotion. Before a plenary session already abandoned by the ruralists, she speaks to the Minister, a catch in her voice. “For years you’ve been saying we would reach this point, and we have. It makes me think about the ignorance we’ve seen [at the session]. What hurts me the most is not understanding how serious what we are experiencing is. We don’t have a Plan B, man. What a failure to commit to the future.” Marina, visibly moved, stood and hugged her.

That night, the Agriculture Parliamentary Front’s Communications office sent out a press release with quotes from Bagattoli and Martinelli. None of what Marina Silva said was included.

Wednesday, September 11. Thanks to the smoke produced by forest fires, for a third day running São Paulo is starting the day as the city with the worst air quality in the world. No problem, if you are at the Rosewood São Paulo, a six-star hotel that extols itself as “a metropolitan oasis […] that occupies one of the area’s few remaining historical landmark buildings and [has] a striking new vertical garden tower by Pritzker Prize-winning architect Jean Nouvel with interiors by the visionary designer Philippe Starck.” Invitations to the Bradesco BBI Agro Summit were only extended to the bigwigs of agribusiness and the city’s Faria Lima financial district.

The audience is almost entirely men, nearly all of them white and dressed in suits, most with no tie. Fernando Honorato, Bradesco’s chief economist, takes the stage. Beaming, he wears a microphone headset, in typical Madonna fashion, to announce the luncheon’s main event: a chat with federal deputy Pedro Lupion, the president of the Agricultural Parliamentary Front, and Mauro Mendes (Brazil Union party), the governor of Mato Grosso.

Fernando Honorato, Mauro Mendes, and Pedro Lupion during a talk at a lavish six-star hotel on September 11, a day when São Paulo had the worst air of any metropolis in the world. Photo: Bradesco Archives

“I think I’m going to have fun with these two public figures, who play a super representative role in the Brazilian economy,” Honorato teases, while waiters begin to move around the room with bottles of what seems to be water and trays filled with cans of soft drinks. “Mato Grosso is the most important state for agricultural production today. Pedro Lupion, one of the country’s most respected parliamentarians, leads the Agriculture Parliamentary Front, which works to defend ag, defend our farmers.”

But even there the smoke had arrived. “I have to talk a little about the fires,” Honorato opens the conversation, speaking to Mendes. Although he recognizes that this is “one of the impacts of climate change,” and that it happens “because of human action,” the governor targets a known scapegoat. “In my state, we have just a few records of criminal things, and also a large number of occurrences that start inside of Indigenous reserves. Because it’s a bit cultural for the Indians to have burns, a mishandling of fire. That takes on proportions, once it leaves the reservation area, in a gigantic radius.” This is a lie. According to data from the Environment and Climate Change Ministry presented one week earlier, 85% of the fires in Mato Grosso started in private areas. Only 10% of the fires are in Indigenous Territories.

When he takes the mic, Lupion swears “we are supporting the most punitive legislation for these arsonists.” However, Bill 1497/2024, one of the most recent he has introduced, mandates that the federal government offer any invader of public lands the opportunity to legalize their ownership of that land. “If there is someone in an area that, after analysis, is found to be federal property, an opportunity to regularize this occupation must be urgently provided prior to any other act,” reads the text’s justification. Two legislative consultants interviewed by SUMAÚMA have no doubt: it is a flagrant incentive for more land-grabbing and fires in the Amazon.

“The fight we are in isn’t [about the] environmental issue,” Lupion says. “This is a lie, it’s what sells newspapers, [it makes] the NGOs money. Our fight has to do with competition,” he says, repeating the lie that the Amazon is defended by people interested in harming Brazilian agribusiness.

Entertained, the bank’s guests lunch and sip wine.

_

Tuesday, September 17 A fire has been consuming Brasília National Park since Sunday. It hasn’t rained for 147 days. The air the people are breathing in the city is considered hazardous for the elderly, children and people with respiratory issues. At Palácio do Planalto, the seat of executive power in Brasília, Lula has gathered the heads of the three branches of government to discuss measures to counter the fires’ advance. On the way out, Arthur Lira, the president of the Chamber of Deputies, tries pumping the brakes on the possibility of harsher penalties for those causing forest fires. After all, the federal deputy says, Brazil’s environmental laws are “the strictest, toughest, and strongest in the world,” and “we’ve tried to vote on matters that strengthen this environmental issue, including with great emphasis in recent years.” Under Lira, the Chamber of Deputies passed the historic cut-off limit for Indigenous demarcation and made it easier to use agrochemicals, among other attacks on future generations’ quality of life.

Three weeks earlier, the Agricultural Parliamentary Front had announced a “coordinated action” to increase penalties on arsonists. Yet none of its leaders appeared to publicly take exception to Lira’s words. Days later, when the federal government announced a decree raising the penalties for environmental crimes, federal deputy Pedro Lupion reacted in a video. “The decree is extremely worrisome, it’s very nefarious.” The Agriculture Parliamentary Front released a statement where it first talked glowingly of the measure before spending considerable space reiterating the need to “prevent farmers from being unfairly punished.” The Brazilian Association of Soybean Growers was more direct: it disavowed the decree and asked Congress for “urgent measures to reverse these absurdities.” In other words: expect a harsh reaction as soon as the first farmer is fined for arson.

“Ag” is on fire. And it is burning out of control in Brazil.

A sun blood-red from fires, as seen from Alto de Pinheiros, a wealthy São Paulo neighborhood. Photo: Paulo Pinto/Agência Brasil

Report and text: Rafael Moro Martins

Editing: Eliane Brum

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

English translation: Sarah J. Johnson

Spanish translation: Meritxell Almarza

Infographics: Ariel Tonglet

Copyediting and finishing: Natália Chagas

Editorial workflow coordination: Viviane Zandonadi

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum