“When we dream, what do we see in our dreams?” asks Davi Kopenawa, shaman and spokesperson of the Yanomami people, in Mãri hi: The Tree of Dream. In this new short film by Morzaniel Ɨramari, the first Yanomami filmmaker, Kopenawa tells how the forest uses dreams to communicate with shamans—“spirit people”—and warn them of impending dangers.

Born in 1980 in the village of Watorikɨ, in the region of Demini, where Kopenawa lives, Morzaniel experienced the first invasion of his people’s territory by illegal miners when he was a child. He witnessed Kopenawa and the photographer Claudia Andujar’s fight to denounce the genocide of his people prior to the demarcation of the Yanomami Indigenous Territory, in 1992. He grew up during the period when the territory was recovering: he studied in the village school, had access to adequate health care, became an Indigenous healthcare agent, learned to make films with the support of government projects, and saw his people grow stronger, something he explores in his first movie, the short Casa dos espíritos [House of spirits; 2010], winner of the People’s Choice award for best film at the Mostra Aldeia SP film screening, in 2014.

Filming his “relatives”—as the Yanomami refer to other members of their people—and, “unlike the non-Indigenous,” not staging any scenes, Morzaniel produces a pure ethnography of how his people live, devoid of the foreign eye that had previously been the only narrator of this story. Morzaniel’s respect for shamanic rituals is evident in his first feature-length film, Urihi Haromatimapë: Curadores da terra-floresta (Healers of the forest-land; 2014), which won Best Picture in the competitive screening at the Forumdoc.BH festival.

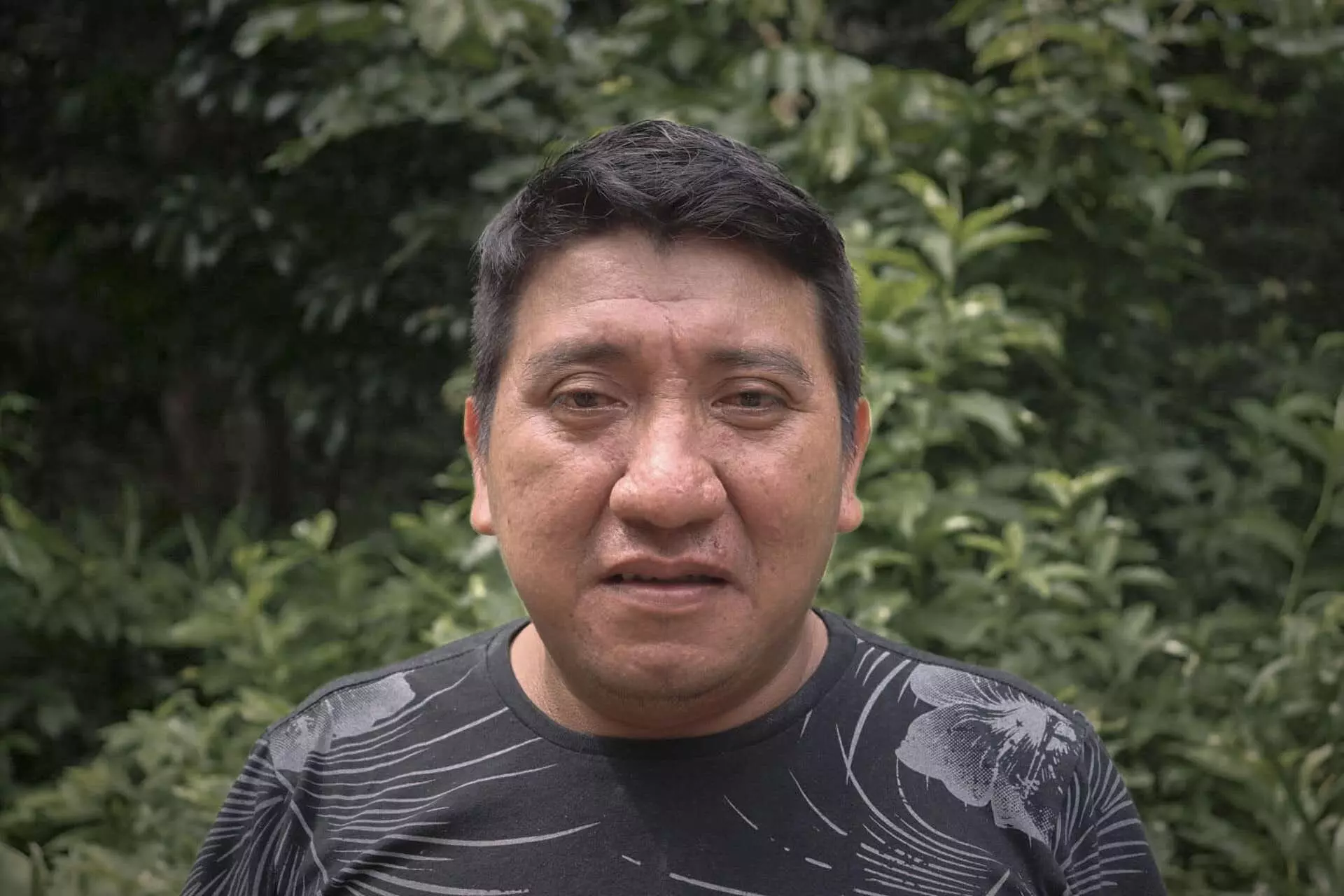

Portrait of director Morzaniel Iramari. Photo: Marília Senlle

Through the eyes of Morzaniel, we see the degradation of the Yanomami Territory over the past ten years. While he enjoyed access to formal education in 2010, his children didn’t, because the school is gone now. The mortality rate skyrocketed when miners brought diseases into a region whose healthcare system had been dismantled. Today, shamans hear the rainforest crying because it has been destroyed, as the filmmaker tells SUMAÚMA in this interview.

“The shamans say the earth has been destroyed. Even the sky has been destroyed.” Morzaniel learned this for himself when he was serving as an interpreter for the teams from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) who have traveled Yanomami territory last year and this. He visited distant villages, where mining has left deep scars. He saw his people suffering from illnesses, getting drunk on the invaders’ cachaça, and asking for help from a healthcare system that has abandoned them. This situation differs greatly from what happens in Demini, where the soil holds little gold and therefore doesn’t attract miners. The film Mãri hi is both an indictment and a plea for the non-Indigenous world to let the Yanomami “live in peace and joy, able to hold their festivals.”

Premiering this month at the film festival É Tudo Verdade (It’s all true), Mãri hi won Best Documentary Short in the Brazilian Competition, meaning it is automatically eligible to run for Best Documentary at the Oscars. In the parallel awards, it earned the Mistika prize in the same category. The film can be streamed on Itáu Cultural Play through April 25. Mãri hi is part of the project “The Falling Sky,” inspired by the book of the same name, by Davi Kopenawa and French anthropologist Bruce Albert. Led by Eryk Rocha and Gabriela Carneiro da Cunha, with production by Aruac Filmes, the project lends support to audiovisual work by members of the Yanomami people and has resulted in two other films: Yuri u xëatima thë – A Pesca com Timbó [Fishing with timbó, a toxic plant] and Thuë pihi kuuwi – Uma Mulher Pensando [A woman thinking], both directed by Aida Harika, Roseane Yariana, and Edmar Tokorino, the first women filmmakers of this ethnic group. All three shorts were featured at The Yanomami Struggle, an exhibit that pays tribute to the partnership between Claudia Andujar and the Yanomami people and that ran at The Shed Museum in New York through April 16, 2023.

SUMAÚMA: What role do dreams play for the Yanomami?

Morzaniel: Shamans dream about many things: the spirit of the river, of the mountains, of the rain, moon, sky, forest, and animals like the jaguar. The spirits send messages. The river warns, “I’m sick now; I don’t feel good. Careful when you drink the water, you’ll get sick.” The forest tells us everything: “Watch out—the forest will vanish. The forest is sick; the climate is terrible; very bad diseases are coming.” They send messages like that.

Publicity release for the film ‘Mãri hi: The Tree of Dreams’

What has the forest said in recent years?

The shamans say the forest used to be joyful. It produced a lot of fruit; there was lots of game. When mining arrived, the forest fell ill. They say the forest is crying because it has been destroyed. Now they say the earth has been destroyed; even the sky has.

The Yanomami people used to have happy, lively festivals, because there was lots of fruit, no diseases, no malaria. Now they say the forest is sad.

When you helped the IBGE census teams, as a Yanomami interpreter, you traveled to many areas within Yanomami Territory. What did you see?

Last August, I started helping staff from the IBGE. They invited me and I went to the Palimiu region, where [miners] had shot at the Yanomami [in 2021]. The land was covered in craters. All the children were sick. There were no more fields because mining operations had come so close. Our relatives were suffering.

At the time, there was no medicine because of the mining. There were many cases of malaria every week. It made me so sad to see how young people had become involved with mining in that region. I had no way of hiding because the miners were so close, right next door. So I started going around the mining area. I found young people working there. Girls fifteen, twenty years old, washing the miners’ clothes, going around the mining area. It was so sad. I nearly cried in Waicás. All the women were over by the craters the miners have opened up.

Working for the miners?

Working for the miners, asking for food, drinking cachaça. In Araçá, the miners gave them lots of cachaça. They took their women. Everybody got drunk, falling over, their wives, their fathers.

Reports say health care has improved for the Yanomami [after the Lula administration set up a taskforce this year]. But it hasn’t. This past March, I was with the IBGE again, this time in the Xitei region. I got there and found all the fathers, mothers, and children crying, asking for health care and medicine. All the children had worms. “Where’s the healthcare team?” they wanted to know.

Later, on March 13, I went to the region of Amazonas with the IBGE census team too. I found the same situation there. My relatives were sick, wanting medicine, but no healthcare teams were coming. I counted two elderly people in the Yawarapi community who were very sick. I got there and the elderly were asking for medicine, asking for help. They were screaming from the pain in their urine, in their bellies.

Then, on March 15, I went to the regions of Kata Kata and Marari. I found the same situation there. Ten children died of malaria in Kata Kata.

Did you still see miners there last month?

I did. They’re still mining there. Staff from the National Force [a program within Brazil’s Unified Health System] has seen it. Other Yanomami interpreters who were with me and the IBGE teams also saw it. They’re still mining there. Miners are still landing their planes in the Alto Catrimani region. When our helicopter flew over, we saw lots of craters.

Do you think you’ll ever be rid of the miners?

I don’t think they’re going to abandon our territory. I lived in the Alto Mucajaí region. Even the Indigenous are secretly bringing the miners in there.

I saw a video recorded by the Yanomami, where the miners are working at night. They hide the machinery during the day.

.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }

You said young people are involved in mining now. Your films depict the traditional way of life of the Yanomami people. Are young people today interested in shamanism? Or in the use of yãkoana [a substance inhaled by the shamans to reach the spirits]?

I don’t think many are interested in it in Palimiu, in Serra Alta. There are no young shamans to continue the tradition; there are no great shamans, like there are in Demini. There are other traditions: dances, songs, painting. But they don’t use yãkoana; they don’t practice shamanism.

In Demini, they want to continue being shamans. They don’t want to do away with shamanism because they say it is very important in helping with disease; it has an important role in curing diseases.

Publicity release for the film ‘Mãri hi: The Tree of Dreams’

What role can shamans play in rebuilding the Yanomami Territory?

They say that when the miners leave, they want to make the forest much better. They say they’ll clear away the smoke, because the miners raised a lot of smoke with their machinery. The spirits [who help the shamans] want to clean the earth again. So the forest will be alive again. The forest is dead today.

Except they can’t, because the miners work with smoke all the time. The miners are still there; they bring in malaria, different diseases. There’s no way they can do this unless the miners leave.

Your 2010 film shows the village school, which had a computer. It talks about the healthcare post, where there was a laboratory that did blood tests. Today, Demini doesn’t have either a school or a lab. Your new film portrays a different forest. Has your situation changed so radically in such a short time?

First, there was a school. It was there because of a project; Davi got the school. There was a laboratory; health care functioned well. Children went to school; even I went. The Indigenous did the teaching. We had everything. It all worked. We weren’t dying because there wasn’t much sickness, much malaria.

Now it’s changed so much. There’s no more school; there’s no quality health care. Things are really bad. There are no more laboratory technicians in Yanomami Territory; they took everything back to the city. So things have changed a great deal. There’s a lot of disease.

.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }

You just returned from New York, along with other Yanomami artists, where your film was featured at the Claudia Andujar exhibit. Claudia played a key role in the demarcation of the Yanomami Indigenous Territory in the early 1990s. Yanomami art has moved onto the world stage. What does this mean for your people’s struggle?

Yanomami lands are being destroyed today. The miners, people from Roraima, don’t respect the Yanomami. I was interested in having my film play outside Brazil because we want to show our struggle.

It was very important to take part in the Claudia Andujar exhibit so we could get support from other non-Indigenous people. She helped demarcate Yanomami lands, and now we’re there with her, showing our image of the Yanomami—how we’re living, how our culture is living, so they can learn about the life experiences of the Yanomami people.

Davi explains it this way: when the Yanomami die, when the shamans die, everyone will die. That’s why non-Indigenous people outside Brazil must get to know our reality. Before I was even born, Claudia had already done a lot. Now we’re arriving where she managed to, in defending the Yanomami people. And today it’s the Yanomami ourselves who are doing it. We’re making art; we’re showing our films.

You were the first Yanomami filmmaker. Is it different when the Yanomami tell the story themselves?

When a Yanomami makes a film, they’re close to where the person is. They see what they’re doing at home. Non-Indigenous [filmmakers] ask the Yanomami to do certain things. I didn’t. I just showed what the people were doing. I filmed what the Yanomami were doing inside their malocas [communal houses], how they live. What we eat, how we live; how we do our work, gather our fruit, things like that. You have to be there with them; get up early, go at night. You can’t stage things. That’s how I started making films. That’s why it’s different.

Do you think audiovisual media might offer a way to revive young people’s interest in the Yanomami culture?

There are a lot of young people interested in doing audiovisual work so they can tell the story to the Yanomami being born now, growing up now. In Demini, when you’re filming, everybody wants to take part, hold the camera. Six young people have already made videos. In other regions of our territory, they’re also interested. That’s why I’m looking for a project to teach young people, so they can learn with me. I’m really interested in teaching.

Spell check (Portuguese): Elvira Gago

Translation into Spanish: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Diane Whitty

Photography editing: Marcelo Aguilar, Mariana Greif and Pablo Albarenga