The first issue of SUMAÚMA, published on September 13, revealed the consequences of deliberate government negligence of the Yanomami Indigenous Land. The biggest demarcated territory in Brazil should be protected by the state, but it has been invaded by about twenty thousand illegal miners with dire impacts: devastation of nature and culture, the rape of indigenous girls, the luring of youth into crime, and the closure of healthcare centers, resulting in the death of nine children in less than three months.

The situation continues to deteriorate due to a lack of effective action by the authorities. Last year, Jair Bolsonaro’s government carried out three operations against illegal mining in the territory, but only after it was ordered to do so by the Supreme Court. In one of those raids last August, federal authorities confiscated 22,000 liters of fuel, three helicopters, three trucks, one quad-bike, around 50 mining tools and a ton of food, according to the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA). This year has seen two more operations, which led to the destruction of mining equipment and structures. However, in all of these cases the miners returned and rebuilt their facilities as soon as the federal police had departed. In the following interview, the government’s lack of results is explained by Hugo Ferreira Netto Loss, IBAMA’s environmental analyst and director of the National Association of Environmental Public Servants (ASCEMA).

Question: The federal government operations were carried out only to comply with judicial rulings. Why did they fail to end mining activities?

Answer: They were not effective in ending mining activities because they did not have any continuity and they lasted for a very short time, 15 days at most. We had a huge success in apprehending a good quantity of equipment, aircraft, vessels and thousands of liters of fuel. But as the authorities stay only for a short time and take too long to go back, the miners can restructure themselves very quickly.

Q: How can this be solved?

A: We would have to have a permanent action of at least six months and only then would it be possible to dismantle mining activities. There are huge logistic difficulties. Access is by three rivers: the Uraricoera, Mucajaí and Catrimani. For part of the year they do not have good navigation because of rapids, so miners choose to go by air. We discovered they have installed more than 200 airstrips outside the Indigenous land, between Boa Vista and Yanomami territory. These airstrips are where they switch transport modes. They take fuel and supplies by truck to these airstrips. And from there they load everything on planes and fly it all on.

These airstrips are concentrated at strategic points. They cannot be too far from cities, such as Boa Vista or Mucajaí, or it would defeat the point of land transport. And they cannot be too far from the Indigenous Land or air transport would be too expensive. As a result, they end up occupying a very limited area, where they can make the connection between the two modes of transportation in an economically efficient way. That is why there is a concentration in one area only. It is a strategic point. And there are the ports too. They use these ports a lot, going as far upriver as they can by car and then switching to river vessels. .

Q: Are the points mapped? Is it known where they are, exactly?

A: They are. That is why whenever an operation takes place, a lot is found.

Q: And if the National Force is deployed there, blocking the roads, would that not be a solution?

A: It is simple. If the Uraricoera river is closed, if a strong base is placed there, in a way that no one goes through, then it is over. In one week the miners within the Indigenous Land would begin to be without food and fuel. In one month the situation would already be unsustainable for them. Closing the rivers alone would have a very big impact because they would have to focus all their effort on aerial logistics. The mining region is a border area [with Venezuela]. It is home to a base of the Special Border Platoon, from the Army, 42 km away from the main mining centers. If an aircraft has to fly around that everyday, all day long, to reach the mining areas, then the miners cannot stand it. And the mining activities are finished.

Q: Have you already informed the government that what is being done is not effective?

A: Yes. The operational plan is not executed. But these small actions are carried out. So, if we did not do even those, imagine how the situation would be? As short as these operations are, they still get results. If we did not have them, it would be much worse.

Q: Does the government give any justification for not executing the plan?

A: No, there is no justification that I know of. My job is to point out the technical and operational solution for the problem and to forward it to my superior. We need means to execute the plan: this many aircraft and public servants, for this much time, with this many support points, in this many places etc.

Q: When you arrive there at the Indigenous Land and see all the structures of the miners, what are your thoughts?

A: I feel revolted. Mining activity is not over because things do not happen. It seems all we need is someone to come and say: ‘let’s do it’. Instead, the mining alerts are just increasing.

Q: What do you see when you get there?

R: There are shops, where they sell everything: fuel, food, internet. There is the mining area, where they use machines. They do not use large-scale hydraulic excavators, like in the Munduruku and Kayapó territories. There are lots of airstrips. It is a mining activity basically fed by helicopters and airplanes. At the same time, we have miners in conditions of misery and total exploitation. It is a very strong contradiction. The owners of the mines and logistics have tens of helicopters, which cost at least three million reais each. And the miners have nothing, only their labour. When someone enters mining activity, normally there is no charge. But in order to leave, one must pay in gold. The miner has to work there until he gathers enough money to leave. And everything he eats there he has to buy it with his own gold. He has to use the gold he digs up to buy food, drinks, fuel, everything. Most of what he gets in the mines he spends on the spot. He is trapped there in a slave-like situation. Whoever defends mining today is also defending this subservience.

Q: Have you seen this happening in the Yanomami Land?

A: I have found many riverine people in the Uraricoera river [close to the Yanomami territory]. One said: ‘I used to work here with fishing tourism. With the folks who came here to fish. I used to take them to the river fishing spots and earned some money with that. Today I cannot do it anymore because mining has destroyed the river’. Today, what this riverine man does for a living is to work in the mines. His island became an island to store miners’ boats. The only work left to him was mining because mining itself destroyed all other income sources.

Q. Bolsonaro has stated that he is opposed to the destruction of the equipment used in illegal mines. There is also legislation in Roraima that says they cannot be destroyed anymore in the operations. What do you think about that?

A. On one hand, these comments have a role in intimidating and denying the authority of those who are carrying out surveillance. On the other hand, they empower and legitimize those who commit crimes. It is a delegitimization of state actions. And they have as a consequence the curbing of surveillance activities.

Q. Would it be feasible to remove the equipment used in the illegal activity without destroying it?

A. There is no way. Picture it: You arrive there and find a helicopter. Who is going to pilot that helicopter elsewhere? When was the last maintenance check of that helicopter? Who checked it? Where did the fuel that is inside that helicopter come from? Is it proper fuel? Is it there because it is hidden or because it is broken? Who will operate a mining machine? We need fuel to take it away. The supply route belongs to the miners. We need to know the road we will pass through. Where do we go in, where do we go out? Is there a bridge? Maybe they destroyed the bridge or blocked the road? Then you take days, expose the surveillance team to all sorts of totally unnecessary risks. And if we leave it there without destroying it, they will use it again.

Translation by Thiago Leal

Civil society and rival candidates: Sumaúma exposé shows “genocidal” Bolsonaro policy in Yanomami Territory

Civil society groups have expressed outrage at the rape of Yanomami women and land that was revealed in the launch edition of Sumaúma, while presidential candidates said the report highlighted systematic abuse.

“The publication reflects very clearly what the mining situation inside Yanomami Territory means, in terms of physical violence, grooming, sexual violence against women, environmental devastation of rivers and soil. In other words, the destruction of a way of living and being in the world”, said Luís Ventura, assistant secretary of the Indigenous Missionary Council. He said this was only possible due to a “gaping omission” by the Brazilian state: “All of it shows an ongoing and striking process of genocide.”

Ana Claudia Cifali, legal coordinator of Instituto Alana, an entity that works in the field of child rights, said the report from Yanomami land showed a violation of the most basic rights: to life, healthy food and physical integrity. “Article 227 of the Federal Constitution regards children and teenagers as absolute priorities. We chose, in 1988, as a society, to put children and teenagers in first place. This has not been fulfilled, especially in indigenous territories.”

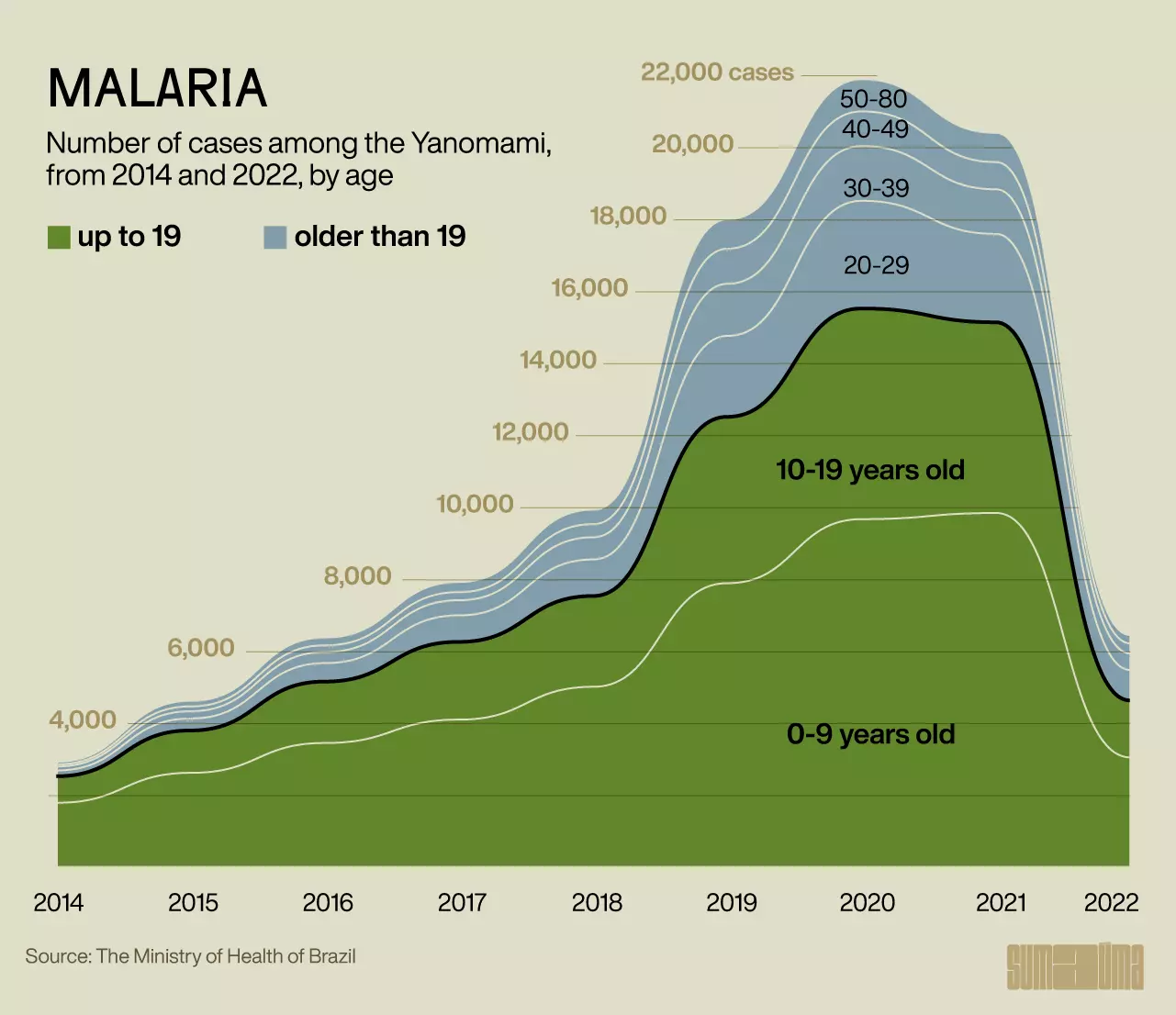

Data obtained by the Information Access Act and published in Sumaúma’s report indicates indigenous healthcare centers inside Yanomami territory have been closed at least 13 times since 2020 due to criminal activity. Today, five of the 37 healthcare centers in the territory are shut down, without any health professionals. As many as 3,485 indigenous people have been abandoned without any assistance during seasons when diseases like malaria break out. Children have died due to a lack of medicine for worms or pneumonia.

“The right to health is established in the Constitution and [Yanomami] children are dying because they lack treatment for trivial diseases, like worm infections. Healthcare centers are closed and workers are afraid of fulfilling their tasks. Tons of hydroxychloroquine were wasted by the president (who wrongly claimed they could treat covid) so today we lack this medicine for malaria treatment in indigenous areas”, said Rosana Onocko-Campos, president of the Brazilian Association of Collective Health (Abrasco). “The facts and figures in the report reveal it is no exaggeration to describe the current president as genocidal. We hope the international courts help us to end this injustice. We need to defend cultural re-establishment. And to hurry to save lives, which is the first step for the fight to go on.”

Through the press office of his campaign, the Workers Party candidate Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva said, “the situation described by the report about the illegal mining in the Yanomami Indigenous Land can only be conveyed with one word: horror”. “The warmongering and aggressive rhetoric of the current president and his aides against Indigenous peoples, Quilombolas and the environment has become a sort of blank check for groups who feel comfortable to go against the law in the territories of vulnerable populations.” Lula’s office said that, if elected, he would reinforce the protection and promotion of Indigenous Lands, as well as other Protected Areas, by strengthening agencies responsible for management and surveillance. It will be a priority to end deforestation and mining in Indigenous Lands and Conservation Units.”

The office of another presidential candidate Simone Tebet, from the Brazil For All Coalition, characterized the reported violence as “absurd”. “It is unacceptable for children to die from a lack of basic medicines like anthelmintics and for indigenous women of all ages to be raped by miners. Unfortunately, this is not only happening with the Yanomami, but in many villages”, the office remarked. “We must rebuild the institutions that deal with the issue, like Funai, which is today in a terrible situation, with low credibility. With well-structured government agencies, it is possible to enforce the law”. Two other candidates Ciro Gomes (PDT) and Jair Bolsonaro (PL) were contacted, but they had not responded by the time of publication.

Translation by Thiago Leal