Schools abandoned or closed, no classes for months on end, a chronic teacher shortage, rain-soaked tables and chairs, and school lunches incompatible with the local people’s way of life. No books, no notebooks, no blackboard, no pencils. There is plenty of nothing, and everything is makeshift in schools on the Rio Xingu Extractive Reserve, in Pará state. Of the few schools that exist, most are in terrible condition. Some don’t even have bathrooms; students say they have to slip into the woods to relieve themselves. During heavy rains, there’s a risk of the structures collapsing.

For five months, MYCELIUM-SUMAÚMA spoke with students, family members, and teachers on the Rio Xingu Extractive Reserve, as well as with education experts, about the government’s failure to ensure differentiated, quality education in traditional communities. At meetings of the Deliberative Councils of Extractive Reserves in the Amazon, it became clear that the situation in Rio Xingu finds echo in Riozinho do Anfrísio and Rio Iriri, two other reserves in Terra do Meio, a region lying between the Xingu and Iriri rivers. In these meetings between local residents and public agency representatives, communities always voice the same complaints and demands about education.

“Together, these three extractive reserves probably total around 1.2 million hectares of forest [4,633 square miles, or two hundred times the area of Manhattan]. Despite this vastness, few families live in the region: 70 in Xingu, 130 in Iriri, and 110 in Riozinho. In total, there are roughly 1,500 people, including children and adults,” says Naldo Lima, technical advisor to the Association of Residents of Extractive Reserves, who is responsible for coordinating social projects.

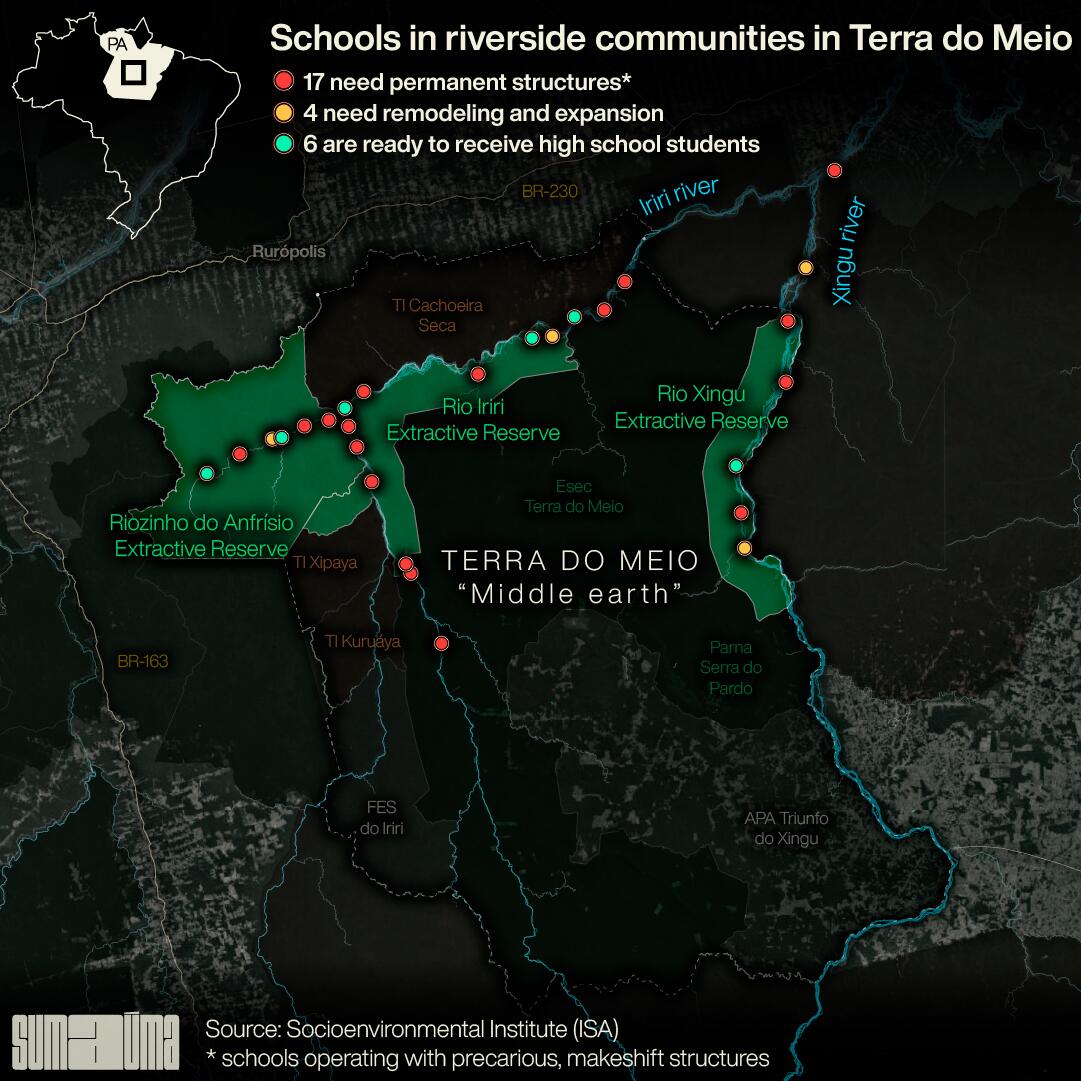

The local residents’ struggle to have schools built on the Terra do Meio Extractive Reserve, or Resex, gained greater traction in 2000. There are currently 22 schools on the three reserves, while another five schools in the vicinity also serve Resex residents. Of this total, 17 schools operate in makeshift facilities with no stable physical structures, often straw huts built by the locals themselves. Mapping conducted by the Socioenvironmental Institute in early 2024 shows that these 17 improvised schools need to be replaced with permanent structures. Another four are in need of renovation and expansion.

Residents of the Rio Xingu, Rio Iriri, and Riozinho do Anfrísio extractive reserves have been fighting for better education since the early 2000s. Infographic: Rodolfo Almeida

According to the Altamira Municipal Department of Education, 375 students are currently enrolled across the three Resexes: 80 in Rio Xingu, 153 in Rio Iriri, and 142 in Riozinho do Anfrísio.

This precarious situation means children, adolescents, and young adults do not have the right to a decent education. Resex residents report that schools are closed or deactivated without any direct dialogue with the community and without considering the immense obstacles of river transportation in the region. Every day, students in these three reserves suffer because the government neglects the educational system in traditional communities.

According to Naldo Lima, technical advisor to the residents’ association, “public authorities lack the political will to understand that—regardless of the number of residents or any other factor—anyone, wherever they are, has the right to a quality education.” Politicians, he argues, only pay attention to “areas where [they] have a bigger number of voters.”

In other words, where there are no votes, there are no schools. “That’s always the case, isn’t it? They’ll always pay more attention to the nearest rural regions, like Assurini [a rural area of Altamira] and other regions where there are more voters,” Naldo Lima says.

“Nothing but juice and crackers”

Maria Beatriz de Jesus Santos, an 11-year-old student at Cristo Redentor Municipal Elementary School in the community of Piranhaquara, near the Rio Xingu Resex, says students leave for school very early and don’t have time to eat at home. Even at such a young age, Bia—as her classmates call her—knows the food at school isn’t good. “Every day, it’s nothing but juice and crackers, or coffee and cookies.” This type of food, served at all the schools on the extractive reserves, ignores the habits and way of life of the children of beiradeiros—as members of traditional forest communities are called. Bia thinks it would be better if the schools served students what they usually eat at home: “Bread, cassava, homemade things, from right here.”

Residents are still hoping to see some change in 2024, with the resumption of the government’s Food Purchase Program, which prioritizes buying food produced on small family farms and extractive communities. But when classes ended in December 2023, the cookies and crackers were still on their plates.

Bia loves school, even with all the difficulties. But she doesn’t like mixed classrooms, where children and adolescents from different grades study in the same space. About to enter 7th grade, Bia thinks everything should be different: “Divided rooms, one for each class. I’d like there to be one room for 6th grade, one for 7th, and one for 9th.” The young beiradeira is already thinking about the challenge of finishing her studies, since the only school in her community doesn’t offer secondary education. “I wish there was a high school here, because at least we’d be closer to our family.”

Nine-year-old Klayne Beatriz da Silva Lopes, who lives on the Rio Xingu Resex, realizes how rough-and-ready her school is. Like Bia, she knows what she prefers for lunch: “Toasted cassava flour with meat or fish.” For Klayne, school is a warm place, because it’s where she learns not just to read and write but also how to communicate as a young beiradeira. And she knows she wants a better school: “They have to repaint and bring in new chairs.”

Children in the Rio Xingu Extractive Reserve complain about the cookies they eat at snack time; Klayne prefers ‘beef or fish farofa’. Photos: SUMAÚMA (snack) & personal archives (Klayne)

The dream of studying and working close to home

Pedrina de Souza Silva, 24, lives and works as a community health agent on the Rio Xingu Resex. Her two children, Klayne Beatriz and Glaelson, attend Baliza School. “I went to school here. I work here with Resex residents. I find it really rewarding to work where I was born and raised.” Pedrina finished elementary school in 2020 and in late 2023 took a General Educational Development (GED) exam to try to earn her high school diploma but failed the math part. Created in 2002, the GED exam offers students who were unable to complete their studies by the expected age a chance to earn their elementary or high-school diploma.

Pedrina recognizes the opportunities afforded by a formal education and believes it is fundamental for people living on extractive reserves to take jobs there. “My children are going to school here. In the future, I want them to graduate and then come work on the Resex too, along with us.”

Andreiz Carvalho Severino, 19, who attended Baliza School on the Rio Xingu Resex, is familiar with the hardships of studying far from home. He lives in the community of Pedra Preta and used to spend at least an hour on the boat in the early morning to get to school. ‘‘If the school had been closer, it would’ve been good. I wouldn’t have to get up so early. I’d have gotten home earlier and had time to do things,” the student says. Andreiz finished elementary school in 2023 and still doesn’t know if he’ll be able to attend high school in the city or if he’ll have to abandon his studies.

The only school in Pedra Preta, where Andreiz lives, has been closed since at least 2018. Parents on this extractive reserve are leaving their homes and moving to Altamira so their children won’t miss out on school. In the opinion of these residents, moving to the city has become the best option, because they feel their children’s education is jeopardized by delays in the start of the school year and the complete closure of some schools.

In addition, students spend significant time traveling to schools in neighboring communities by boat—and then risk arriving to find no teacher or classes. Not to mention the problem with boat skippers, who stop working when they can’t afford fuel because their pay is late, and then the children have no ride to school.

When asked by SUMAÚMA, the Altamira Department of Education said that in the last three years, the current administration didn’t close a single school: “On the contrary, we opened three more schools and created three centers to better serve communities.”

Children from extractive reserves travel to school by boat, a journey that sometimes takes hours

Children aren’t the future; they’re the present

Rayna Costa do Nascimento, 25, teaches at Cristo Redentor School in the community of Piranhaquara and lives on the Rio Xingu Resex. A graduate of the Terra do Meio Extractive Reserve Teaching Program, designed by local leaders with the help of the Federal University of Pará (UFPA), Rayna says it’s important for schools to be staffed with teachers from the region, who are familiar with the reality of people living in Amazonian riverside areas. “We’re familiar with local culture. Only we know the challenges these communities face.”

Teachers who come from the city, Rayna says, often leave because they can’t adapt to the horrendous classroom conditions or cope with the hazards of life in the deep forest—including jaguars and insects, part of routine life for beiradeiros. For outsiders, the noises they hear seem like a kind of Capelobo, a hairy, people-eating creature with a loud shriek. But beiradeiros know this sound is produced by howler monkeys. The legend told by ancestors in the Xingu is that when an Indigenous person living in isolation in the forest is around 90, they turn into a Capelobo, with hair covering their whole body, except their mouths and navels.

“Sometimes teachers can’t adapt to the physical structure of the schools and so they give up and go back to teach in the city,” says Rayna. According to her, the students also have difficulty learning because school facilities are deficient and non-local teachers are not committed enough. Rayna says another problem is they don’t have adequate teaching materials, citing the subject of traditional knowledge as an example. “There is no suitable material for teaching this subject, so we have to do our own planning and that’s a bit difficult, because it isn’t part of the state curriculum. It should be, so we can increasingly value local culture and afford our students a quality, differentiated education, tailored to traditional and beiradeiro communities,” Rayna says.

Despite these many obstacles, Rayna has an encouraging message for the youth on extractive reserves: “Don’t give up. Always pursue your goal. Fight. I started school late, when I was 16. Now I’m 24, and I was able to graduate from the Extractive Reserves Teaching Program and be accepted into a federal university. […] We always have to fight for a differentiated, quality education. […] Young people are the future of Resexes, and they need to be seen. We’re stronger together.”

Valdinéia dos Santos Silva is a 35-year-old teacher from the “beiradeiro community of Maribel, on the left bank of the Xingu.” She says, “I’m also from a traditional people. I graduated from the Terra do Meio Extractive Reserve Teaching Program.” Under this project, Resex residents took a training course during high school and went on to form much of the teaching staff in Terra do Meio classrooms today. For Valdinéia, when a teacher comes from a traditional community, they are “very familiar with the reality of this population and the students” they work with. These teachers find it easier to communicate with students because they know the beiradeiro way of life, says Valdinéia. After all, that’s where they were born and raised.

“It’s discouraging”—for both teachers and students

Every school in the Middle Xingu region has serious infrastructure problems, according to Valdinéia, and this is detrimental to learning. “We don’t have adequate infrastructure, and that affects us a lot. For example, at the school where I work, everything gets wet when it rains. Sometimes students even find it hard to get to school because of this situation. It’s discouraging, you know, when someone has to study at a school in these precarious conditions.”

Even though Valdinéia thinks it’s important for these communities to have access to differentiated education and decent, more spacious facilities, the teacher feels the Department of Education “doesn’t provide the support we need to really make a difference here.” According to her, “the Department of Education should take a broader view, not just send in teachers and leave us to do the rest, right? It’s very hard for us alone, as teachers [without the department’s support], to do this work.”

According to Valdinéia, teachers are under a great deal of pressure from the Education Department because of the dropout rates. But the situation, she argues, is aggravated because schools lack structure and there is no secondary education in the region. “They keep putting pressure on us, and yet the facilities aren’t suitable for working or even studying.”

Rayna (left) and Valdinéia (right), both native to the region, teach on the Rio Xingu Extractive Reserve. They believe educators need to understand the beiradeiro’s way of life. Photos: personal archives

“Teachers pretend to teach, and we pretend to study”

The lack of quality education doesn’t harm children and adolescents alone; it also affects adults who want to study. Manoel Resende da Costa, 53, lives on the Rio Xingu Resex. As a boy, he completed 8th grade in the town of São Félix do Xingu. When he returned to his home village and wanted to resume his studies as an adult, he noticed the difference: “Going to school here is real hard, because some teachers who come from the city just pretend to teach, and we pretend to study.” Some teachers aren’t interested in understanding their students’ challenges or adapting to the local culture, and this hampers the education of children and young people in the community, Manoel says.

“You need to have qualified teachers who can respect and be respected. Differentiated education means respecting our rights,” says Manoel, who would like educators to observe beiradeiro tradition and culture as well as community calendars, with their own specific holidays. Critical of politicians, Manoel sums up the dilemma of education on extractive reserves: “The problem here is a lack of public policies and planning to improve things on the Resex, so everyone can go to school. We know we have this right, but it doesn’t happen.”

“Beiradeiros have the right to quality education. It’s the law”

Despite the sad educational reality in these traditional communities, there are still people who believe beiradeiros can change the scenario.

Fifty-year-old Augusto Postigo is a teacher who was born in São Bernardo do Campo, in São Paulo state, and has worked in the Amazon since 1998. “I’m an anthropologist. I graduated from Campinas State University.” His first stop in the Amazon was Acre state, where he worked with extractivist communities in the Upper Juruá. “They were also descendants of rubber tappers, families with the same history as people here, from the beiradão [Amazon riversides]. I came to Altamira in 2011 to do research in these communities. Since then, I’ve been working on the three extractive reserves,” the anthropologist says.

Augusto teaches Territorial Management to community residents, through the Socioenvironmental Institute. The young people and adults who attend these classes learn more about their own history, origin, and identity, of which they are proud. “Beiradeiros have every right to a good-quality education because they are traditional peoples and communities. There is a law guaranteeing this right,” he says.

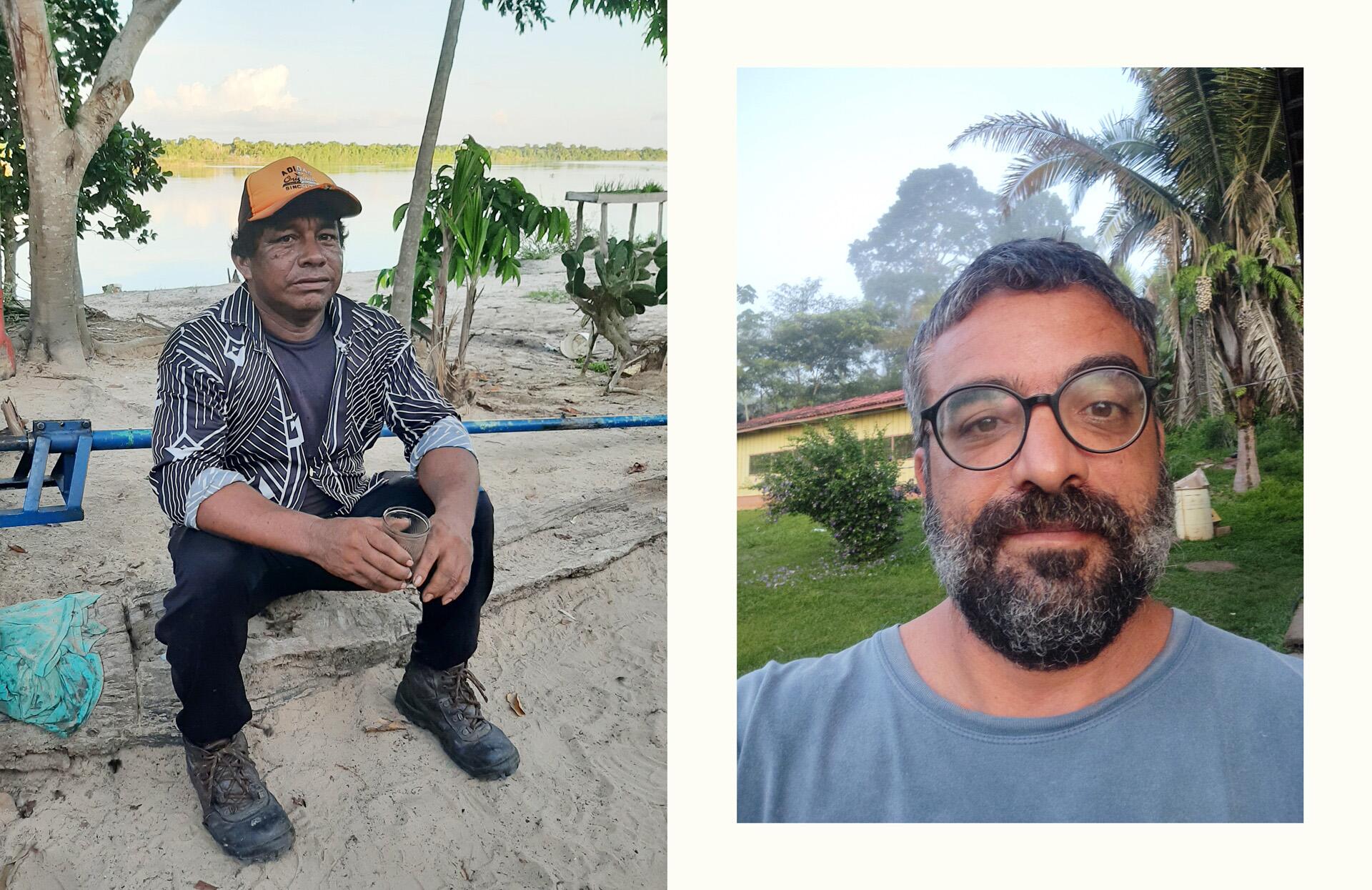

Manoel (left), resident and student on the Rio Xingu reserve, is tired of ‘pretending to learn.’ Teacher Augusto Postigo (right) says quality education is a right. Photos: SUMAÚMA (Manoel) & personal archives (Augusto Postigo)

In 2007, Brazil adopted a National Policy for the Sustainable Development of Traditional Peoples and Communities, enacted under Decree No. 6.040 during Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s second term as president (2007-2010). The policy is meant to “foster the sustainable development of Traditional Peoples and Communities, with an emphasis on recognizing, strengthening, and guaranteeing their territorial, social, environmental, economic, and cultural rights while respecting and valuing their identity, forms of organization, and institutions.”

The classes in Territorial Management taught by teachers like Augusto help beiradeiros discover their right to health and quality education, even though the government always argues there are many roadblocks to providing schools and healthcare posts on the reserves. “The State practically got here just a few years ago, and on a small scale. Few of the rights enjoyed by most Brazilians—or at least a good share of them—don’t exist here yet. People here need to know these rights, these laws, and understand what place they occupy in the country. Forest peoples are guardians of the forest and should be recognized by society as a whole,” says Augusto.

On rainy days, water is everywhere in the Baliza community school. Desks and tables are damaged, and there is no way students can study or learn. Photo: Manoel Barbosa

“It’s not a lack of money—it’s a lack of political will”

What is needed to improve education in traditional communities? How can government administrations be sensitized to these people’s lack of access to what is a right, to an education with dignity? Residents of extractive reserves ask these questions constantly. “It’s not a lack of money. It’s a lack of political will to invest the money where it should be invested. It’s a lack of vision, a lack of courage,” says Raquel Lopes, professor at the Federal University of Pará (UFPA), who holds an undergraduate degree in linguistics and doctorate in anthropology.

Currently a professor with the rural teaching-license program at the Federal University of Pará, Raquel was one of those responsible for designing the Terra do Meio Extractive Reserve Teaching Program in 2016, which trained about 70 students who live on the region’s reserves. The professor had her first contact with the traditional communities of the Middle Xingu in 2011, when she was invited to work with the Territorial Management course. At the time, residents were reporting problems in the schools involving interactions between teachers and the community. Raquel says many of these stories entailed “sexual abuse and alcohol consumption by the teachers,” which put students in situations of risk and vulnerability.

Raquel saw first-hand the hardships faced by these families because schools weren’t offering quality education. As part of a team, she listened to the children and parents talk about their complaints and about what kind of school they would like to see on reserves in the future. “We asked how a school could contribute to their future plans,” Raquel says. “What school do you want? What school would be good for you?” Most residents wanted schools to be run “by local people,” according to Raquel. This is the main reason the Extractive Reserve Teaching Program restricted its enrollment to students living on reserves.

Only one group of students graduated from the course, which ran from 2016 to 2023. Raquel thinks the government isn’t interested in opening a new teacher training program and will only do so if the community exerts pressure. “Education, like love, is kind of a leap of faith. You don’t look after a child because they’re going to look after you in the future. You look after them because you love them, you want them to be well. We educate not because these children are going to give back, become leaders. We educate them because they have the right to an education; they have the right to a better life. Whether they take a certain job or not, that depends on how their training goes and how communities get involved in this process of making political demands,” the professor says.

In Raquel’s opinion, change only happens when a community organizes collectively. “When people ask me if there’s going to be another teaching course, I tell them to sit down and mobilize the community because, to a large extent, the course only happened because people effectively demanded it. It arose from these complaints, from this anguish, from pain,” she says.

Based on her own experience, Raquel says an educational project will only be successful if it has ties to traditional communities and territories. “The hurdle is the view taken by the Brazilian State, which is still very much stuck in the school model of the last century. This has to do with local disputes over minor power. There are various issues, but I think the teaching course showed it can be done.”

School calendar, electoral calendar

On December 4, 2023, leaders of the Rio Xingu Resex met with representatives of the Altamira Municipal Department of Education to demand the city meet deadlines for the start of construction of a new school in Baliza, scheduled to begin that month. The meeting was held at the office of Education Secretary Maria das Neves. Residents made it clear to the city that it would be impossible to hold classes in the current facility, badly damaged and never intended to be a permanent structure.

Talks with the education secretary have been dragging on for months. Resex residents said that in July of last year, the municipal education department made a commitment to deliver the school by December 2023. At another meeting held in December in an attempt to resolve the issue, the education secretary and community representatives signed a document in which the municipal administration pledged to begin building the school by January 6, 2024, so students could attend the new facility when the school year commenced in March.

Everyone returned to their communities in the hope Baliza School would get off the drawing board and on to firm ground, but so far this hasn’t happened. According to local residents, the education secretary claims the drought in the Amazon delayed construction, because it affected transportation of materials down the Xingu River. But for the community, this is no excuse, because the Xingu remained navigable even in the drought. In a note to SUMAÚMA, the education department said it is waiting for suppliers to deliver building materials before sending them to the community. “Regarding the start of the school year, we are finalizing the process of teacher staffing and training and will begin classes on March 16,” the Altamira Mayor’s Office and Municipal Department of Education promised.

Students say the bathroom at Baliza school on the Rio Xingu Extractive Reserve is in such bad shape they prefer to slip into the woods to relieve themselves

The case of Baliza School is yet another example of the community’s relentless struggle. As the 2023 school year drew to a close, the Altamira Mayor’s Office issued a decree aimed at reformulating the educational system in both urban and rural areas. The municipality claims that more than 25,000 students are enrolled in 52 urban and 103 rural schools and that this reorganization is needed for financial, budgetary, and fiscal reasons, since revenue fell in 2023. The decree defines the minimum number of students required for a school to operate.

When asked by SUMAÚMA, the Mayor’s Office replied in a note that schools will not be closed on the extractive reserves: “The goal is to meet needs in a responsible fashion and foster quality education, consistent with current legislation and in line with community demands. It is important to underscore that schools will not be closed. What is happening is a reorganization and restructuring of the educational system.” With election year disputes looming at the local level, the Mayor’s Office said it “reaffirms its commitment to education and the ongoing quest for excellence on behalf of citizens.”

The Ministry of Education and Culture informed SUMAÚMA that the federal government “has continuously made efforts to ensure that states, municipalities, and the Federal District effectively implement the National Education Policy for Rural Areas. But the ministry also disclaims responsibility for oversight of what actually happens at schools on the reserves. “It does not fall to [the ministry] to demand or define the implementation of actions or measures by federated bodies” to guarantee the quality of education offered in remote locations, such as extractive reserves, according to the ministry’s note.

In a lengthy email replete with citations of laws and articles, the clearest, most direct message was this: “Management of Extractive Reserves falls outside the responsibility of MEC [Ministry of Education and Culture].” According to the ministry, monitoring the availability, operation, and quality of education falls to the National Institute for Educational Studies and Research. SUMAÚMA contacted the institute’s press office but had received no response at the time this report was concluded.

In its replies to SUMAÚMA, the ministry stressed education is a fundamental right of citizens and a duty of the State: “It is not enough to merely ensure the provision of education and access to schools as a right of the population anywhere within Brazilian territory; this right must also be guaranteed, while observing the social and cultural features and socioenvironmental and economic contexts where each population lives.”

In April 2023, the federal government reopened the National Council on Traditional Peoples and Communities, which is supposed to listen to what the residents of these areas have to say about public educational policy. While recognizing the absence of data and information on schools on these reserves and underscoring state and municipal responsibilities in the functioning of schools, the Ministry of Education says it “fully believes in and works resolutely toward the implementation of differentiated education as a right of peoples living in rural, riverine, and forest areas.”

SUMAÚMA asked the Pará State Department of Education about residents’ demand for the provision of secondary education in communities on extractive reserves. In response, the department’s Coordination Board for Education in Rural, Riverine, and Forest Areas said it had launched a survey in January 2024. “We are going to evaluate the situation so we can then organize supply,” board coordinator Joana Machado said. Resident associations representing the reserves lodged this demand at a meeting held in December 2023.

In February 2024, children and students across Brazil were preparing for a new school year. Construction of the Baliza community school hasn’t even started yet. Nobody knows for sure when classes will begin on the reserves—it might be March; it might be April. Some years, classes didn’t even begin until September, according to local residents. For traditional communities, the school calendar is uncertain. What’s certain is the electoral calendar. Politicians never forget that one.

At Baliza School, on the Rio Xingu Extractive Reserve, where the author of this report attends classes, students organize to demand a new school building

Patricia Lima, 28, lives in the community of Baliza, on the Rio Xingu Extractive Reserve. She wasn’t born a beiradeira but that’s how she defines herself today—and “with great pride”—because she feels the forest completes her, and it’s in the Xingu that her soul resides. This forest journalist was born in Marabá, Pará, where she lived until she was 17. She married at 13 and had her first child at 15. Her first marriage left her with marks of suffering. She moved from Marabá to São Félix do Xingu with her mother and child. Three months later, she fell in love with Ivanildo, with whom she had four more children. Ivanildo was born on the banks of the Xingu, and Patrícia has always been fascinated by the stories he tells about his childhood and family.

For Patrícia, living in a place that has a river and a forest is truly life in paradise. Her favorite place is the riverbank. Ivanildo used to be a fisher, and Patrícia learned this trade from him. For a while they lived as nomads, “from island to island,” working for fish vendors. But her dream was always to settle down in a home in the forest, plant cassava, and work the land. This happened when she and her family moved to an extractive reserve eight years ago. She immediately identified with the beiradeiro way of life. Patrícia finished 9th grade in 2023 and is now fighting to be able to attend high school in her community. All her children go to school, except the youngest, who is still a baby. As a communicator from an extractive reserve and a scholarship holder in the Mycelium program, Patrícia carries within her a piece of the river, of hunting and fishing, and of biodiversity. She is happy because the forest always welcomes beiradeiros, its true guardians, with open arms—and because she lives as part of a community. That’s why she will continue to fight for beiradeiros’ right to quality education.

***

The Mycelium-SUMAÚMA Forest-Journalist Co-Training Program began in May 2023. Fourteen young people from the Middle Xingu—four Indigenous youth, three youth from traditional forest communities, one from a quilombola community, one small-hold farmer, a fisherwoman, an Indigenous health nurse, and young people from urban communities in the city of Altamira—participate in gatherings in the forest and the city. The youth are guided by senior journalists at SUMAÚMA, known as “seed-mentors,” who are in turn guided by the youth, since co-training is an exchange. In this report, the seed-mentor of the forest-journalist Patricia Lima was the journalist Malu Delgado.

Coordinated by Raquel Rosenberg, co-founder of Engajamundo, the teaching method used by Mycelium-SUMAÚMA, deliberately eschews any type of orthodoxy. Conceived by Eliane Brum (likewise responsible for supervision and content) and Jonathan Watts, the program maintains the rigor, responsibility, and accuracy of traditional journalism.

Micélio-SUMAÚMA also includes psychoanalyst Ilana Katz, providing care consulting, and producer Thiago de Sousa Leal. Mônica Abdalla is responsible for managing the Program’s finances, with administrative and financial assistant Marina Borges and financial consulting from Mariana Zahar. Micélio-SUMAÚMA receives funding from the Moore Foundation and the Google News Initiative.

Editing: Malu Delgado and Eliane Brum

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Célia Arruda

Spanish translation: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Diane Whitty

Infographics: Rodolfo Almeida

Copyediting and finishing: Érica Saboya

Editorial workflow: Viviane Zandonadi

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum