After sixty-two hours resisting the confusing stream of waters drowning his neighborhood, painter Moisés de Carvalho, 43, finally understood that the course of the river that had bathed his childhood was no longer the same. He spent two nights and three days along, stranded on the roof of his house – the only place in his home the water had not reached – waiting for the nearly thirty-meter-high Taquari River to retreat. The same river that, as he recalled, used to welcome the region’s residents. “I remember well. That’s where we swam and fished. But not now. Firstly, because there are no more fish. Secondly, because we are no longer familiar with today’s river. I’ve lived here for four decades since I was born. I’ve never seen anything like it,” he says.

Moisés lives in Lajeado, one of the cities in the Taquari Valley, in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, in southern Brazil, that were slammed by intense storms in early September, followed by historical flooding. The river that gives its name to the valley rose so much that it reached the second highest mark on record 29 meters and 62 centimeters – in the municipality of Estrela, located on the bank opposite Lajeado.

The Taquari swelled in the wake of other extreme climate events in southern Brazil, happening in sync with one of the most severe droughts ever in the country’s north – a dramatic situation that has gone on for weeks in the Amazon region.

In June, in Rio Grande do Sul, an extratropical cyclone clipped the coast, leaving sixteen dead. While in the second half of July, another cyclone dragged at least three people to their deaths in the same region (along with one in São Paulo and another in Santa Catarina). In early September, dozens of cities in Rio Grande do Sul were immersed by floods. Thousands of residents lost homes and at least fifty people died when they were swept away by the current.

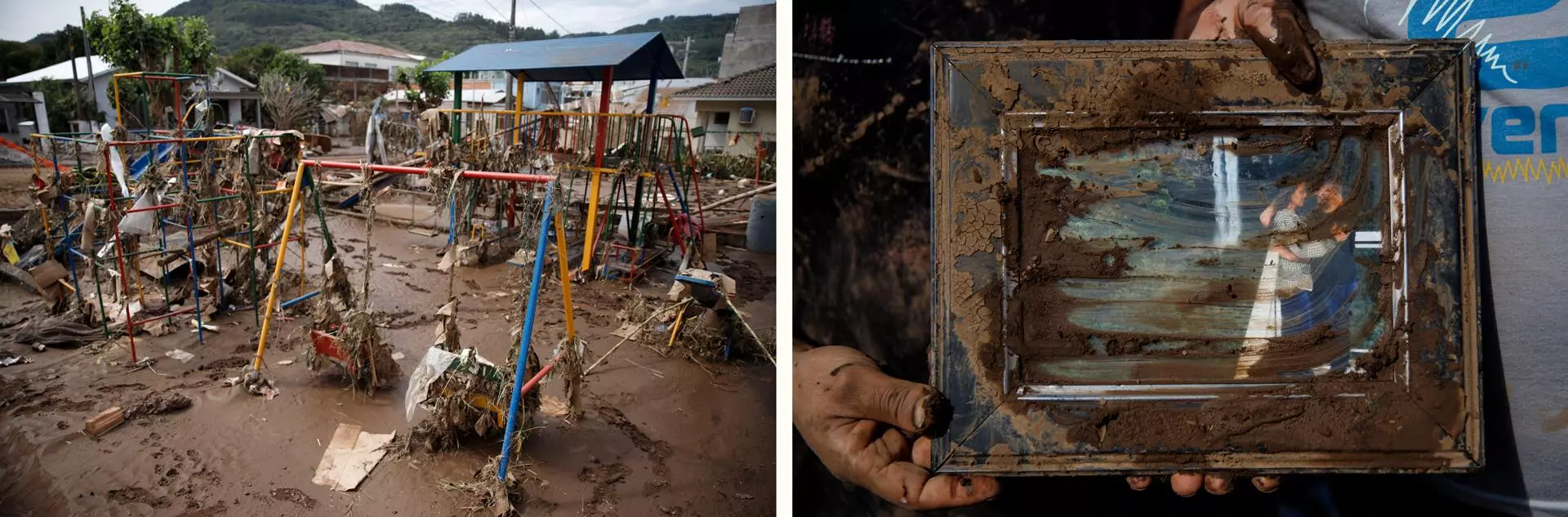

The destruction in Muçum, a municipality in Rio Grande do Sul, one of the hardest hit by the cyclone and heavy rains in the region. Photo: Jeff Botega

Some of their calls for help still echo in Moisés’s mind: “Nights were very confusing. All you heard was the torrent of the river and screams and cries for help. Then suddenly, it all calmed down and there were hours of silence.”

While the south was fighting to stay above water, a lack of it in the north began to turn dire. In late September, the governor of Amazonas declared a state of emergency in fifty-five municipalities because of the worsening drought and increased outbreaks of fire in the state, which had the worse rate of blazes for the year. In addition to Amazonas, Acre, Rondônia, and Roraima have been facing a critical situation because of the prolonged drought and low river levels. The Amazon River, one of the world’s longest watercourses, had already dropped to an astonishing 7.35 meters at the end of September (the outflow for the last twenty years during drought times is 4.38 meters). This has led some of its tributaries, like the Tefé River, to practically dry up. Others are at such high temperatures that animals are suffering and dying.

Transport of food and people is hindered, and the traditional forest peoples living along the river, known as ribeirinhos, are suffering from food insecurity. On the Solimões River, wide swaths of land are emerging from what used to be the river’s flow, stopping the lives of those born and guided by the waters’ movement. “In my father’s day, he said this river would change. Now I see he was right,” says Ruth Martins, 50, a ribeirinha.

A resident of the Mamirauá Reserve, in the municipality of Uarini, in the interior of the state of Amazonas, she says that for a few decades you could dock your boat along the edge of her community. Now, during the drought, you have to travel at least forty minutes on foot, on scorching earth. “The reserve, created along the river’s banks, is now very far from the water. It’s so hot here. I’ve never seen it so dry, such a different climate. We’re trying to buy water to drink, because the river water is stagnant and the rain can be bad for our health, from all the smoke in the air,” she says.

The forest burns in the municipality of Canutama, Amazonas, in August: destruction and deforestation are moving forward at an intense clip. Photo: Marizilda Cruppe/Greenpeace

The situation is so serious that the drought is moving toward a tragic record and, according to the federal government’s National Center for Natural Disaster Monitoring and Alerts (Cemaden), it’s expected to last until at least December. Over the coming months, the situation in thirty-eight of the Amazon’s most important rivers should remain critical, with levels below historical averages. While intense rains in the country’s south should continue causing damage through the end of 2023. “I don’t know if what is happening is because of man or nature. All I know is that the way things are, it’ll get worse, right?” asked Moisés.

We are nature, but many of us forget this. And maybe that is why it is so hard to answer Moisés’s question. “What happened is a natural thing, Moisés, and it was led by one of nature’s most destructive creatures: man,” I explain.

Indeed, today science has proven that it is because of man that the world is hotter and hotter – more precisely, 1.1 degrees Celsius hotter than the average pre-industrial temperature. And these downpours accumulating a month’s worth of precipitation in just one day, like the droughts extending longer than many lives can bear, have everything to do with this.

With the planet’s temperature rising, various weather processes are affected, including the cycle of water evaporation and heat absorbed by the ground. Intensified evaporation, for example, drives the formation and strength of rains in certain regions, making them more prone to storms. In other areas, droughts are drawn out.

While steering his boat, a man looks at the desolate scenario of dead fish in Lake Piranha, in Manacapuru, Amazonas, a region affected by the drought of the Solimões River. Photo: Bruno Kelly/Reuters

The most recent report published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has already shown that the frequency and intensity of these events are greater in a hotter world. Yet as with any phenomenon of nature, flooding in the south as well as the droughts in the north are the result of a combination of factors that, insofar as they are interwoven, give previously common events a catastrophic scale. “These extreme events occurring in Brazil bear the signature of climate change. The planet is hotter, the oceans are anamously hotter, and El Niño come into this year intensifying these events,” explains climatologist Francisco Eliseu Aquino, of the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul.

According to the specialist, El Niño – a climate event happening every three to five years on average, when the waters of the Pacific Ocean near the equator, are hotter than normal – is caused by weakening of the trade winds, which are constantly blowing from the tropics to the equator and which, because of their high humidity, cause rainfall. The result is a longer drought period in Brazil’s north. Except that on the other side of the world’s largest rainforest, the northern Atlantic Ocean has also recently undergone an anomalous heating process, making it harder for humidity to reach the Amazon and reducing rainfall.

“In the country’s south, El Niño is causing a change in the circulation of winds from the tropical region to the polar region of the southern and northern hemispheres. This change alters the circulation of high winds, jet streams, and conditions the formation of extratropical cyclones, which end up blocking cold fronts in the region over a longer time, intensifying storms. Add to this the fact that South America is hotter – in fact, this was the hottest winter on record for the region in over 100 years – causing a backfeeding process of these severe storms,” Aquino explains.

But it does not stop there. The destruction of the Amazon, which in 2022 alone lost 10,573 square kilometers of forest because of predatory human action, according to a report from the Amazon Institute of People and the Environment (IMAZON), reduced the biome’s capacity to spread humidity to other regions, deregulating the rainy and dry seasons of the Amazon and of the rest of the continent, which affects the planet’s climate.

Residents of Muçum rescue objects after death and the destruction of homes and public spaces in the city. Photo: Jeff Botega

One study published in 2019 showed, for example, that this devastation has a direct impact on precipitation volume in South America. And because in nature everything is circular, in addition to these direct impacts, the annihilation of the biome is an important and systematic contributor to the planet’s heating.

Today Brazil ranks fourth on the shameful list of the world’s biggest greenhouse gas emitters. While the energy sector is chiefly responsible for putting other nations at the top of the list, in Brazil the climate crisis is mainly attributed to land use: fires and deforestation precede the opening of lands for pastures and mass agricultural activities, such as soybeans, the main export of this sector, corn, and sugarcane.

For some time now science has been tasked with showing this intricate, interdependent, complex and delicate network of lives that constitute and are constituted by Earth. Also showing that the Cartesian perspective, based on the foundations of an industrialized society, which continues to dominate most of Western thinking, has destabilized these vital cycles with devastating effect. It is hard for us to see it, because understanding the environmental crisis means giving up a centuries-old conceptual system based on the idea of man as its center and nature as a resource, relating development to domination and starting with the principle that evolution only occurs when man separates from nature. This means breaking the false idea that we are in control of our surroundings and renouncing the premise that everything natural exists to serve, threaten or satisfy man.

Moisés and I talked about the science behind the environmental crisis and how measures are insufficient to repair the damages being caused in the region. Yet after hanging up the phone to let him enjoy a reunion with his family – his wife and children, ages 7 months and 11, who had left their home at the beginning of the flood and found shelter in a school gym – I thought that perhaps the easiest way to reflect on this tragedy would be to open the windows of our homes. On that same day when we spoke, I saw that the horizon was difficult for us both. The sky was gray in various cities of Rio Grande do Sul: it was the first time in the year when the smoke from burns in the Amazon had traveled over 4,000 kilometers southward, reaching the state. Whether by the winds currents, by the force of the rains or the intensity of heat, for a long time science and nature itself have raised the alert about what is happening, shifting man’s view from his own bellybutton and getting him to look at the real center of the world – the one that carries the only future possible.

Jaqueline Sordi is a biologist, journalist, and environmentalist. She holds a specialist degree in Sustainability from the University of California (UCLA) and a PhD in Communications from the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul.

Fact check: Plínio Lopes

Spell check (Portuguese): Elvira Gago

Translation into Spanish: Julieta Sueldo Boedo

English translation: Sarah J. Johnson

Photography editing: Lela Beltrão

Page setup: Érica Saboya

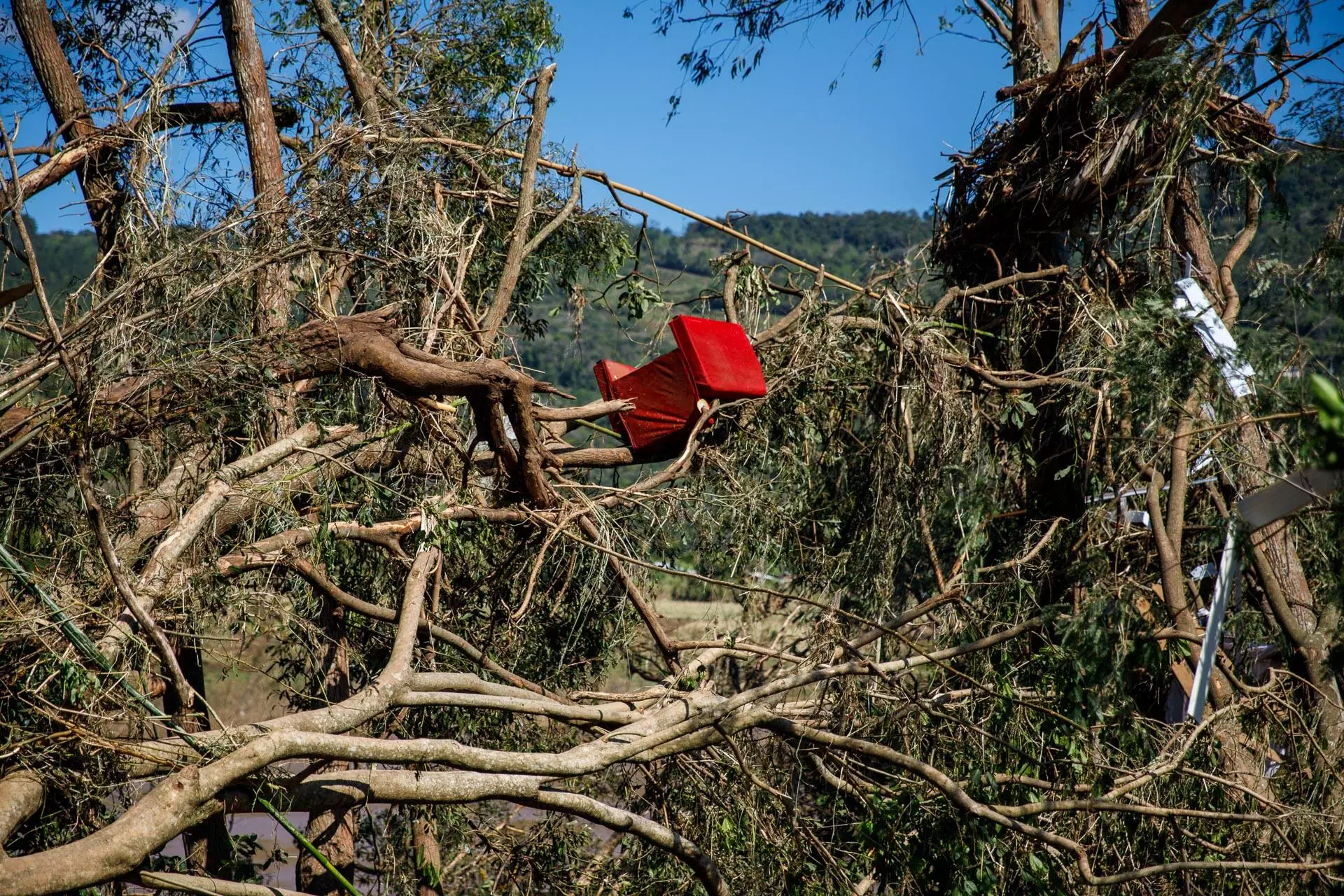

Out of order: after a cyclone devastated the municipality of Muçum, in early September, a couch lies amidst downed trees, showing the scale of the wind’s strength. Photo: Jeff Botega