Half of the indigenous lands illegally exploited by gold miners in Brazil are territories where uncontacted peoples live. This is one of the findings of the study Uncontacted Peoples hanging on by a thread: Risks Imposed on Uncontacted Peoples, published in January of this year by the Coordination of Indigenous Organizations of the Brazilian Amazon (Coiab) and the Environmental Research Institute of the Amazon (Ipam).

The researchers’ analysis also identifies the five greatest threats these groups face, most of the time in an overlapping way – more than one or all of them at the same time: the first is legal and institutional instability, because many lands have not been certified and this increases their vulnerability to territorial disputes and violence; next comes illegal deforestation, followed by burning, land grabbing and mining.

These populations can be exterminated if the violations to the environment, their way of life and their health are not curbed. In order to achieve this, institutions need to be strengthened and act quickly. How? By demarcating land. By expelling invaders and by guaranteeing fundamental rights.

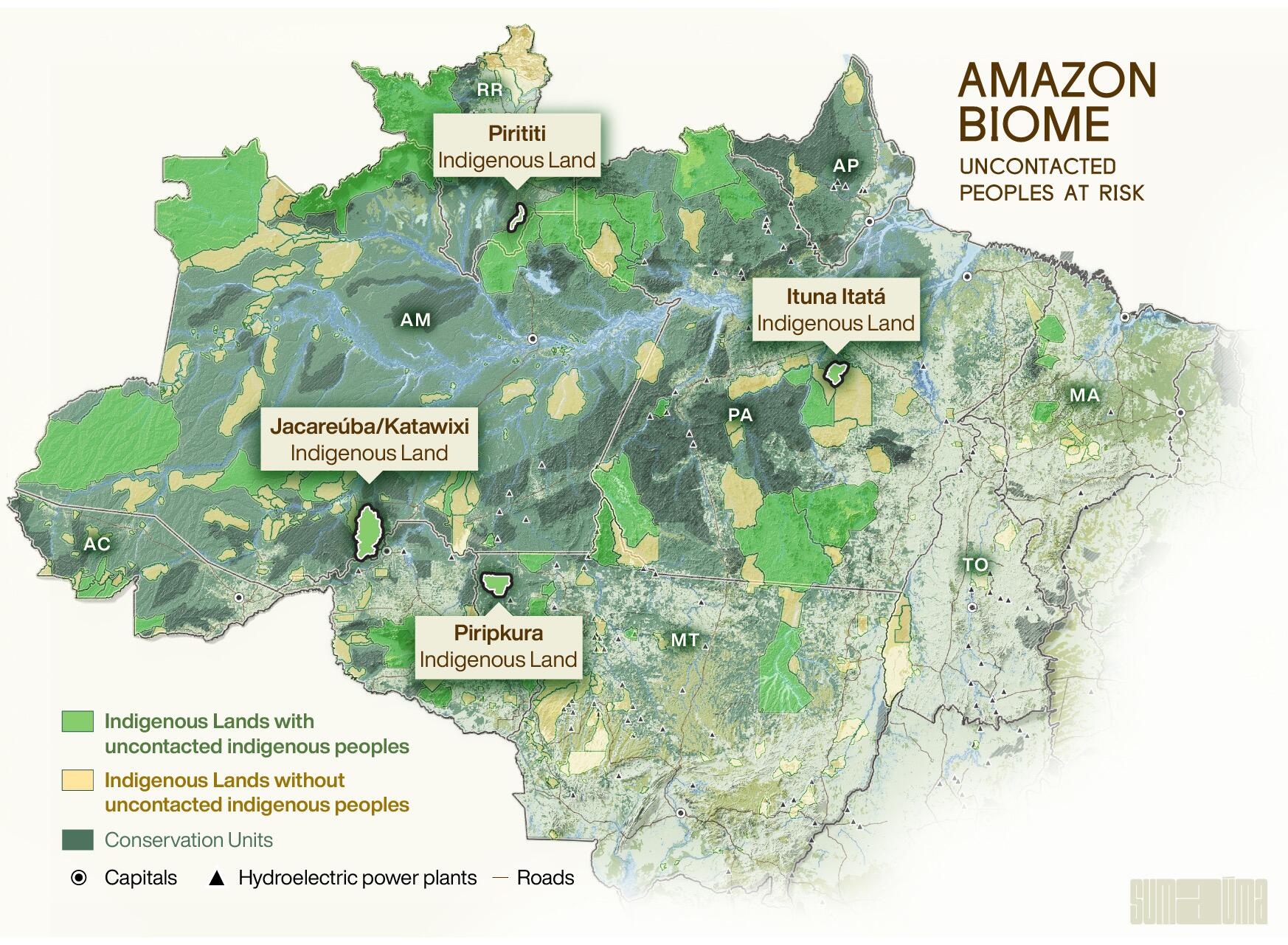

The territories that are currently in the most serious situation are the Ituna-Itatá indigenous land (in the State of Pará, close to the Belo Monte hydroelectric power plant), the Jacareúba-Katawixi indigenous land (close to the agricultural expansion between the states of Amazonas, Acre and Rondônia), the Piripkura indigenous land (considered to be exclusively for the use of uncontacted peoples and which is suffering from deforestation and land grabbing in the State of Mato Grosso) and the Pirititi indigenous land (which is being affected by infrastructure construction work on the BR-174 highway in the State of Roraima).

SOURCE: IPAM AND FUNAI (2022). INFOGRAPHY: RODOLFO ALMEIDA/SUMAÚMA

Data from the Observatory for the Human Rights of Uncontacted and Recently Contacted Peoples (OPI) sent to Lula’s government’s transition group alerted the new administration that these indigenous lands that were in an emergency situation were the very same ones that had their use restriction ordinances under constant threat during Bolsonaro’s administration, which repeatedly refused to renew them and only gave in after a legal ruling. The purpose of the ordinances is to safeguard uncontacted peoples and protect their territories so Brazil’s main indigenous entity, the National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples (Funai), can do the work of identifying and monitoring the area until the process of finalizing this territory’s demarcation is completed.

No other country in South America has more uncontacted peoples than Brazil. Maybe no other country in the world. Funai registers the existence of 114 groups. Twenty-eight of these groups have confirmed presences and territories that have been defined by Funai, and are just waiting to be officially recognized as indigenous territories. A further 26 are under study and 60 are reasonably well documented. But the actual number may be even higher, because there are cases where Funai has not yet made a statement regarding locations found by Ethno-Environmental Protection Fronts (FPE), which are field units under the System for the Protection of Uncontacted and Recently Contacted Peoples (SPIIRC).

The uncontacted people have resisted constant violence and numerous attempts at forced contact. Bolsonaro cut Funai’s resources, particularly those earmarked for the program for the Protection and Promotion of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which included the protection of their territories. Moreover, during his term in office, the former president put in charge of the indigenous body the police chief Marcelo Xavier, an anti-indigenous who persecuted countless leaders and organizations, such as the National Coordination of Brazil’s Indigenous Peoples (Apib), the current minister Sonia Guajajara and the indigenous leader Almir Suruí who were accused of “spreading lies” about the Bolsonaro government.

The uncontacted and only recent contacted indigenous peoples have distinct characteristics, languages, traditions, and their own social structure, which are guaranteed in the Federal Constitution by Articles 231 and 232, and are entitled to have their territories recognized and demarcated. Nelly Marubo, who works for Coiab and is an expert in projects related to the management of uncontacted and recently contacted peoples, explains that invaders, such as gold miners, loggers, and illegal fishermen, are important threats. “They [the invaders] leave the indigenous territories in a critical situation. They contaminate the water in such a way that, in addition to causing fish and other types of game to become scarce, these indigenous people end up catching skin diseases and other types of illnesses, which can lead to death, because they [uncontacted indigenous people] have had no contact with the diseases from here, from this society, and this is worrying,” states Nelly.

Yanomami Genocide

Malnutrition, contamination by mercury, violence, rape, deaths and social impacts are the problems identified by leaders of Brazil’s largest indigenous land, that of the Yanomami. In this territory, the presence of isolated peoples has been confirmed, and the violence described in this report puts the lives of these indigenous peoples at risk of genocide. In recent years, the people who should have helped protect these spaces did nothing effective, as shown in SUMAÚMA’s special coverage of the case, when it revealed in February that at least 570 children died of preventable diseases.

According to the president of the Urihi Yanomami Association, Júnior Hekurari Yanomami, during Bolsonaro’s administration Funai took very little action and this had an impact on the lives of the recently contacted and uncontacted peoples. “Funai did not operate in any comprehensive way within Yanomami territory. Sometimes it made donations, or took part in operations, but in a very distant way”, he says. “We got no support whatsoever when we really needed it, and no meaningful response as to what they would do in terms of finding ways to remove the invaders.”

The indigenous leader says that the uncontacted peoples even avoid contact with the Yanomami. “They are afraid and whenever they are discovered they change their location, which is why it is necessary to protect the territory, because we are the ones who can protect them,” explains Júnior.

Never again?

A tragedy. That is how the Funai employee, Rodrigo Ayres, who is an indigenous expert with the Madeirinha-Juruena Ethno-Environmental Protection Front, views the actions of the Bolsonaro government in relation to the uncontacted peoples. “Bolsonaro was a tragedy, a disaster. We can’t even say that it was neglect, because we had a public policy that was deliberately created for the purpose of handing their territories over to environmental criminals, including the harassment of civil servants who put up stronger opposition to these attacks. An apocalyptic scenario that needs to be investigated. Bruno Pereira’s murder, which I actually talked about with him at length before it actually happened, his actual death represents the apex of this policy that was planned and executed against the uncontacted peoples. Bruno gave his life for the cause, and his leaving shook the world,” stressed Ayres.

With a lot of emotion, Ayres, who for the last five years has experienced the resistance of these peoples, highlights the importance of society understanding this struggle is not just one for indigenous people and indigenous experts, but one for all of humanity. “It is heart-warming to see the strength and resistance of these peoples, who prove to us every day that there is another way of organizing socially,” he says. And he gives some examples: “The way in which Tanaru [the last survivor of the genocide of his people and known as the Indian of the hole] lived, resisted and who remained alone in the forest for more than twenty years, refusing contact with non-Indians. The Piripkura, of whom only three survivors of massacres remain, still manage to smile and sing”.

For Ayres, this resilience is even more remarkable given the extreme vulnerability of these groups who live under pressure in places that are much desired by economic actors. “As uncontacted indigenous people who depend solely on the forest for their survival, and who have no immunity whatsoever to non-indigenous diseases, the growing pressure on their lands increases the risk of genocide. The net is closing, because the expansion and colonization fronts are getting closer and closer, and the areas of forest are shrinking. It is an extremely worrying situation, which deserves the proper attention both on the part of the State as well as on the part of society,” says the indigenous expert.

The danger is permanent, society is being warned about a genocide. There are miners, businessmen, politicians and evangelical missions that threaten the lives of these people. Immediate action is urgently needed to protect these people and their territories.

Will Funai write a new story?

A lawyer and the first indigenous member of the Brazilian congress, Joenia Wapichana is the new president of Funai. For the very first time, Brazil’s main indigenous body, which was founded in 1967, has an indigenous president. In relation to the uncontacted peoples, Joenia confirms she will fulfill Funai’s mission as an institution, but she knows she faces many challenges, largely because of the degree to which the foundation was dismembered in recent years.

“I have to fulfill the institutional mission, Funai wasn’t observing it and thatlet a lot of invaders in, there was no permanent protection policy,” says Joenia. “What happened in relation to the murder of Bruno Pereira and Dom Phillips is an example of how things were working inside Funai. We have already had a few meetings with some of the leaders of the Javari Valley, with employees who work with the uncontacted and recently contacted indigenous peoples, and we know how important it is to have a more serious and responsible policy, so it is precisely with this line of thinking that we are going to operate,” she states.

Joenia recalls that the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples, which is headed by Sonia Guajajara, has set up a department for the sole purpose of strengthening this area [the anthropologist Beatriz Matos, who is the widow of the indigenous expert Bruno Pereira is heading up the Department of Territorial Protection and of Uncontacted and Recently Contacted Peoples]. And she adds: “Funai also has to operate along these lines, because today the priority is a clear, efficient and effective policy in keeping with more on-site reinforced monitoring, so this is how it has to act, fulfilling its institutional duty”.

Regarding the budget, the agency’s president says that there was an increase of a little more than 100 million reais from 2022 to 2023, but that this is not enough. “It has to look for alternatives for a budget that will enable it to fulfill, among other things President Lula’s own campaign promises.” Funai’s budget that was signed into law in January 2023 is one of just over 514 million reais. However, the value of the program Protection and Promotion of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples is roughly 80.5 million reais and, out of this amount, 40.4 million reais is earmarked for Regularization, Demarcation and Monitoring of Indigenous Lands and the Protection of Uncontacted Indigenous Peoples.

Spell check (Portuguese): Elvira Gago

Translation into Spanish: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Mark Murray

Photography editing: Marcelo Aguilar, Mariana Greif and Pablo Albarenga