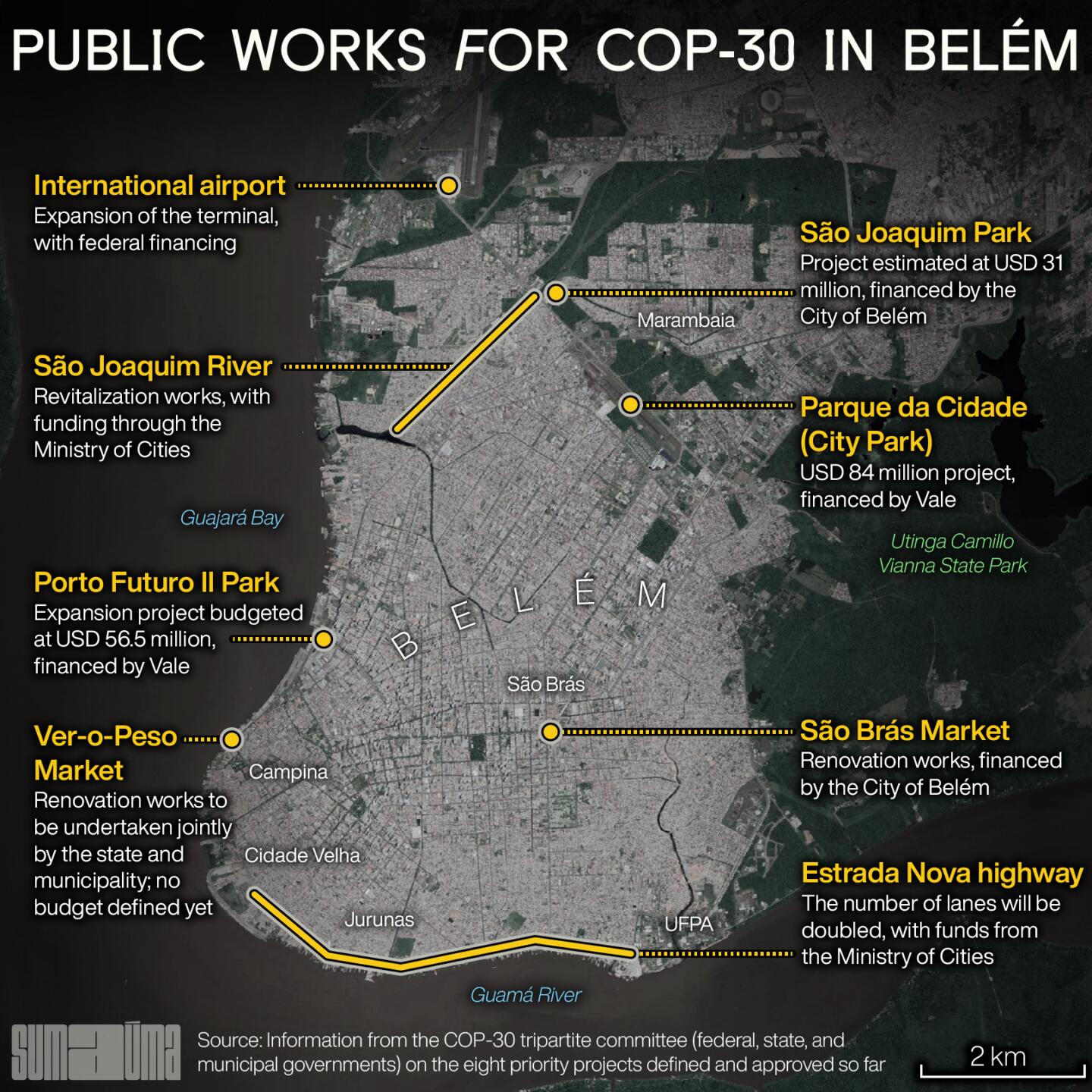

In two and a half years, the 30th United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP-30) will be held in Belém, the oldest capital of northern Brazil. Time is not on the side of the urban developments that are needed in the areas of large-scale infrastructure, tourism, mobility, and logistics to remediate the socio-environmental shortcomings of Pará’s capital city in advance of the climate summit. In November 2025, Belém means to introduce itself to the world as a postcard of sustainability. Yet several problems and inconsistencies could jeopardize the image that Governor Helder Barbalho (Brazilian Democratic Movement), Lula’s closest government ally in the Amazon region, wants to sell the world. Among these inconsistencies is the fact that two of the main works announced by the Pará government—a new Parque da Cidade and Porto Futuro II, an expansion of a park near the docks—will be funded by the transnational mining company Vale. Tied to two of the worst environmental disasters in Brazilian history—the collapses of the Mariana and Brumadinho dams, both in Minas Gerais—Vale has also been accused by Indigenous communities, such as the Awá Guajá people, of assaulting the forest and violating the rights of its inhabitants. The company represents everything the planet has to overcome to curb global heating, a topic that will be discussed at the largest climate conference in the world, scheduled to be held in the capital of the Brazilian Amazon for the first time in its history.

Climate villains funding climate summits has been a hallmark of these conferences. Everything points to COP-30 following the same trend. “Large corporations have gradually and visibly appropriated the global climate agenda,” affirms Marcela Vecchione Gonçalves, professor at the Nucleus of Advanced Amazonian Studies at the Universidade Federal do Pará. A research specialist in climate funding, the regulation of mitigation banking, and adaptations to climate change, Marcela recounts her shock when she saw the list of sponsors for the 2015 climate conference in France, when the Paris Agreement was signed. “And who were these sponsors? Energy companies, oil companies, agribusiness companies. They were all there, out in the open.”

Govenor Helder Barbalho (Brazilian Democratic Movement) and President Lula (Workers’ Party) hold the paper making Belém the official host of COP-30. Next to Lula is Belém’s mayor, Edmilson Rodrigues (Socialism and Liberty Party). Photo: Alessandro Falco/SUMAÚMA

Professor Gonçalves points out the obvious inconsistency: “If we look at [greenhouse gas] emission sources and the industries tied to the main sponsors of COP-30, they are precisely the ones responsible for the highest global emissions.”

One of the country’s “largest mining complexes”—complete with mines, plants, and rail and port logistics services—is run by Vale in the state of Pará. The government’s justification for their partnership is that the company “will provide the expediency and resources needed for progress to be made on construction of these public works.” Under the helm of Helder Barbalho, the youngest member of the controversial Barbalho clan, the government also sustains that Vale has a debt with the state that needs to be settled.

The world’s largest open-pit iron mine, located in Carajás in the state of Pará, is owned by Vale. Photo: Daniel Beltrá / Greenpeace

In the course of its 80-year history, Vale has left several environmental, social, and labor violations in its wake. The International Alliance of Men and Women Impacted by Vale, founded in 2009 with the support of academics, environmentalists, NGOs, and community associations, issued a report in 2021 that highlights the violence that occurred in the mining giant’s area of exploitation, a debt that has yet to be paid.

Through its press agency, Vale announced that the estimated cost of Parque da Cidade is USD 84 million and USD 56.5 million for Porto Futuro park. “The company has adhered to the state program, Estrutura Pará. This initiative aims to strengthen our public-private partnership as well as the state policies for developing and expanding public services,” the company stated in a note to SUMAÚMA. “The projects began in May and are currently in the definition and planning phase. The next step is to hire suppliers and execute the public works.”

Professor Gonçalves believes it will be important to pay close attention to how the partnership between companies and climate funding will unfold in the Amazon, “especially in terms of appropriating the bioeconomy and biodiversity agenda. It’ll be interesting to see who the major sponsors of COP-30 in Belém are going to be,” she notes. Based on information released by the municipal and state governments, Vale is the most controversial private-sector financial backer to date.

A comprehensive array of environmental problems

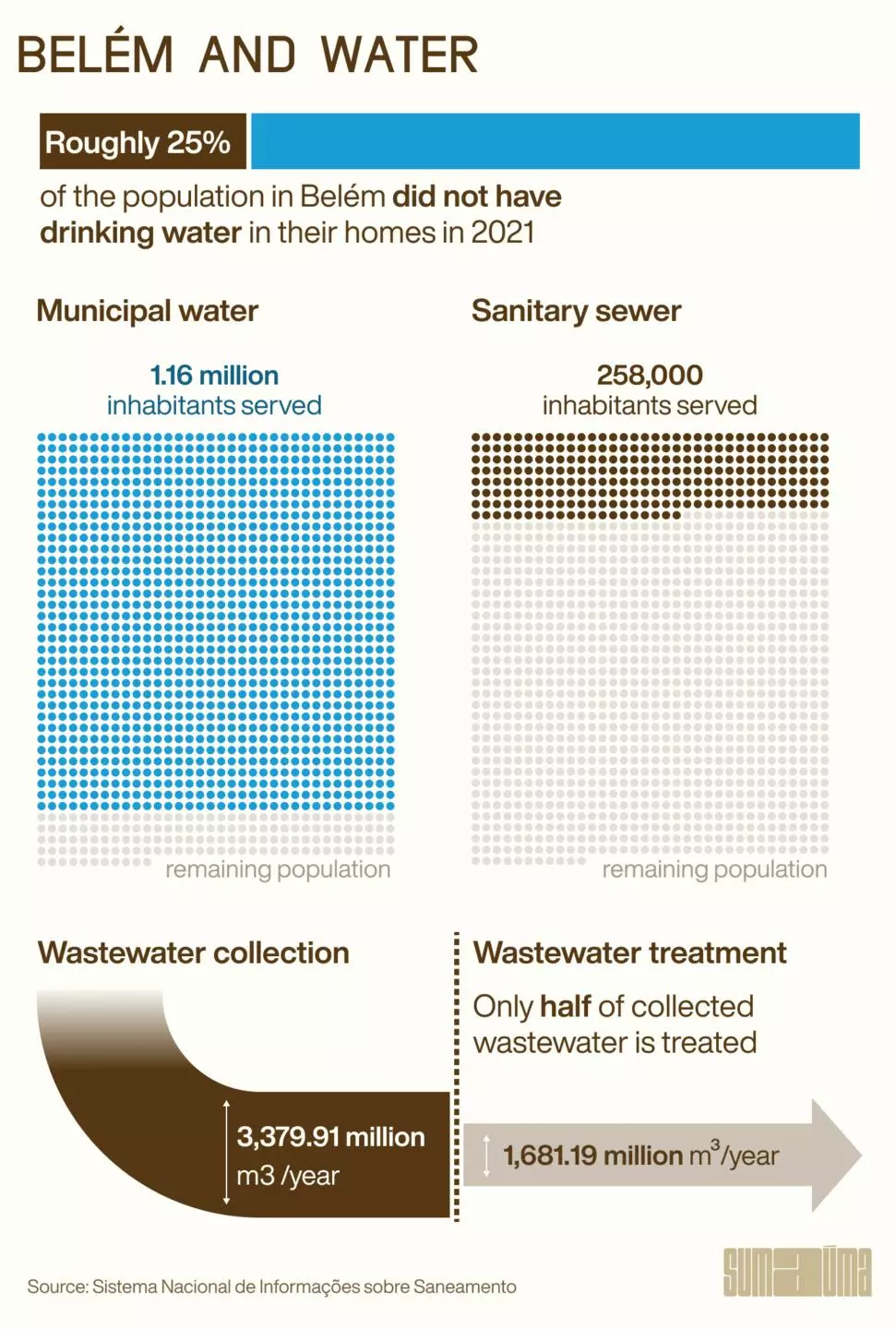

“COP-30 Polygon” is the name given to an area of approximately 11.5 square miles that extends from the historic Cidade Velha all the way to the Marco neighborhood by way of the historic Ver-o-Peso waterfront market, the neighborhoods of São Brás, Sacramenta, and Guamá, and the Val de Cans International Airport. It spans the neighborhoods with the most expensive real estate in Belém. COP-30 Polygon sections off a portion of the city that would never be considered the gold standard for good environmental practices: as of 2021, the last year for which data is available, close to 25% of the capital’s residents did not have drinking water in their homes. According to the National Water and Sanitation Data System (SNIS), 83% of residents across the city do not have basic sanitation. And only 3,400 cubic meters of the sewage and wastewater collected annually have been treated, according to the same source. The Mayor’s Office itself has noted that 15% of residents do not even have basic waste collection services.

Vila da Barca: in the COP-30 Polygon, the ribeirinho community on the banks of Guajurá Bay is an enclave of resistance. Photo: João Paulo Guimarães

The United Nations’ decision to hold the most important environmental event of the planet in Belém in 2025 creates a window of political opportunity for Governor Helder Barbalho, Mayor Edmilson Rodrigues (Socialism and Liberty Party), and most of all President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (Workers’ Party), whose international credibility hinges in large part on his “sustainability” platform.

The three politicians have pledged to make the most of this short period to “modernize” the city by resurfacing the busiest roads with a more resistant, less oil-based asphalt, installing metal poles with solar panels, running electrical wiring underground, and adding more buses (there are 1,300 in circulation today), both electric and gas-powered. The more than 2.3 million people currently living in the metropolitan area of Belém, however, struggle to envision the positive impact COP-30 preparations may have on their daily lives.

In this article, SUMAÚMA looks at sectors of Belém that have been totally sidelined from any debates about the urban and social interventions made with the climate summit in mind. Yet these same sectors are the ones who are now and will continue to be hardest hit by the climate crisis—the poorest among the population. If the only thing those most affected by heating in the fast-deteriorating Amazon region can hope for is a seat at the construction site, COP-30 may just fail before it even begins.

In the middle of the road there was a garbage dump—and then another, and maybe another

Former trash-picker Lika has always lived in the Aurá Dump Site, one of the most blatant symbols of the inequality and socioenvironmental issues in Belém. Photo: João Paulo Guimarães

Far away from the COP-30 Polygon, both in terms of geography and the social pyramid, Eliane Gomes do Nascimento, also known as “Lika,” still doesn’t know what the 2025 climate summit means, nor its purpose. Lika once made her living scavenging recyclables. She spent 30 years, including her childhood, living in what is popularly called the Aurá Dump Site. Now 42 years old, Lika has been in and around the dump from the day it opened to the day it closed. She now lives in the Jerusalém community of the Águas Lindas neighborhood, just minutes from Aurá. The dump is located in Ananindeua—the second largest city in Pará and in the Belém metropolitan area—where current Governor Helder Barbalho began his career and served as mayor for two terms.

The Aurá Sanitary Landfill, as it is officially called, is one of the most blatant symbols of the inequality and socioenvironmental issues that have yet to be dealt with in the Belém metropolitan area. The dump site was installed in the end of 1989 toward the BR-316 highway that connects Belém to the rest of the country and around which the city began to grow in the second half of the 20th century. Aurá was closed 25 years later for failing to comply with federal regulations for solid waste, and currently serves as a dumping ground for debris within the Belém Environmental Protection Area.

Even though the dump was closed in 2015, hundreds of families continue to make a living from sorting and selling debris to buyers in the vicinity. Lika sometimes returns there to scavenge for sheets of plywood and textile that she then uses to create crude walls for the rooms in her new house, built in a neighboring community.

“My mom and dad moved here. We were the first residents. Back then, we had a charcoal oven because Dad used to make charcoal for us to use and him to sell,” she said. “We picked fruit too because there are areas in our community with lots of fruit. After a while, they opened this garbage dump.” The house Lika moved into with her parents and five other children was built out of pieces of wood covered in cardboard and black tarp. While living inside the dump, Lika would go out night and day to scavenge food for her family, as well as the clothes, furniture, and utensils they used at home.

Lika lived on top of the dump’s tons of trash alongside other grownups, children, and elderly people who were exposed to pollution and disease while scavenging for food scraps and basic sustenance. Families sorted through PET bottles, glass, and objects made from iron, plastic, rubber, and wood found in trash bags dumped there by garbage trucks. The work was grueling, and many died under the wheels of trucks whose drivers unknowingly rolled over bodies covered by makeshift cardboard blankets that shielded them from the cold yet also exposed them to death.

The closure of the Aurá Sanitary Landfill did not end the cycle of indignity. Another site was opened in Marituba, a city around 14 miles from Belém. It is scheduled to close this coming August. Guamá Resíduos Sólidos, the same company behind the Marituba Landfill, may open a third one in the municipality of Bujaru. The company announced its plans to install a new industrial complex that would include a landfill, recycling facility, composting yard, thermoelectric plant, and center for environmental education.

In August of last year, residents of Bujaru and Acará, two cities near the Belém metropolitan area, protested the project, which they claim could affect 17 quilombola communities [communities of descendants of fugitive enslaved Africans], as well as areas with freshwater springs and other resources essential to the region. Now that Belém has been selected to host COP-30, the state and municipal governments are promising to finally provide selective waste collection service across the city. To date, there have only been a handful of private, one-off initiatives as well as some offered by cooperatives. The city has opened a public procurement process to implement an organized system for selective waste collection in the capital before the earth summit.

Belém’s stilt houses massacred by luxury condominiums

Vila da Barca: an urban development and housing project was initiated in 2003 for this long row of stilt houses overshadowed by luxury condominiums, never to be completed. Photo: Alessandro Falco/SUMAÚMA

How can Belém get the infrastructure it needs to host close to 60,000 visitors, which is the number of people authorities estimate will be attending COP-30? The question hovers over the capital of Pará. One project anticipates dredging Guajará Bay to make room for ocean liners that would serve as hotels for conference participants. This is one way to sidestep the inability of Belém’s hospitality sector to accommodate an event of this size. According to a survey conducted by the Brazilian Hospitality Association, Belém has approximately 12,000 beds, which means an additional 48,000 would have to be generated to cater to the summit.

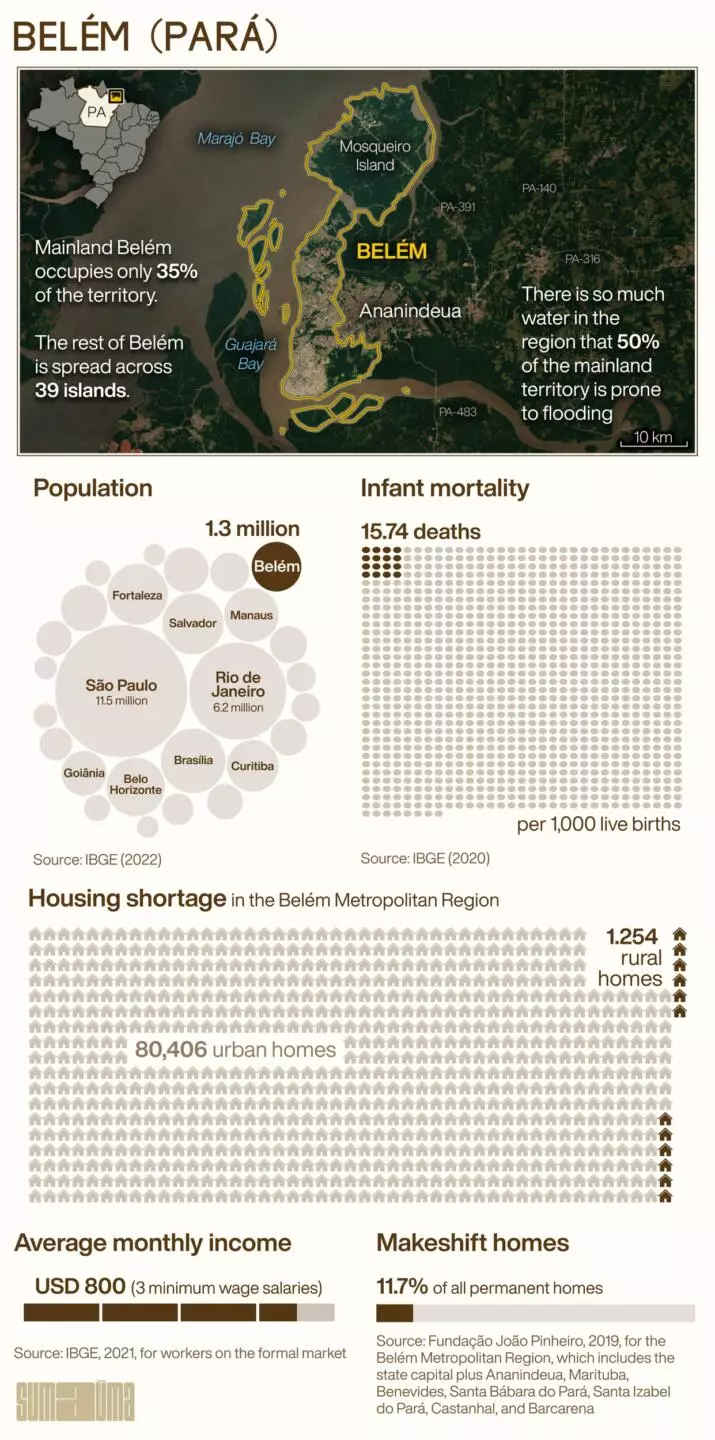

The most important issue, however, is to stop COP-30 being used as an excuse to evict ribeirinhos, members of traditional forest communities who continue to resist in a city that is growing ever more vertical in an unending war against nature. Belém is cut through and surrounded with rivers and tributaries, dividing the city into a mainland area that corresponds to about 35% of the territory and an area scattered across 39 islands, the majority of them containing vast swathes of jungle. There is so much water in the mainland area that about 50% of the land is prone to flooding. Urban development projects with high backfill and drainage costs continue to ignore the natural presence in the city of rivers, tributaries, and streams.

Located inside the COP-30 Polygon zone and near the new Parque Urbano Igarapé São Joaquim, Vila da Barca has stood its ground for almost a century as a ribeirinho community embedded on the banks of Guajará Bay. This enclave of resistance, which today spans close to 20 acres, is being increasingly overshadowed by dozens of luxury condos raised on Avenida Pedro Álvares Cabral and on another bastion of memory, the small alleyways that snake between the 19th-century, working-class houses in the Telégrafo neighborhood.

In 2003, the city of Belém initiated a project in the area, known for its long rows of stilt houses. The project remains unfinished and was taken up again in 2021 when Edmilson Rodrigues was reelected as mayor. The Mayor’s Office press department says the city has pledged to deliver “198 houses to the families who have been awaiting the project for years,” by January 2025.

In the mid-20th century, as the city began to grow skyward and sprawl toward the newly built highways, its retreat from the rivers became more and more clear. From the 1990s onward, a wall of buildings was raised along the riverbanks in mainland Belém. This kind of construction runs counter to the way life is organized across the dozens of islands where ribeirinho houses overlook the bay or nearby canals or tributaries and where small towns or communities form around the riverbanks. Much like Vila da Barca, the first outer areas were “pushed” to the lowlands, which tend to be humid and susceptible to flooding, a typical feature of floodplains, and where local authorities rarely provide any basic sanitation.

“We know Vila da Barca is in the most expensive area of Belém per square meter, so the fact that the project stalled is also connected to the power of real estate,” said artist Maurileno Sanches, former president of the Vila da Barca Neighborhood Association. He has no doubt that delays in the housing program are related to the high levels of real estate speculation in the area. “Our community is a sign of resistance in Belém, so we have to overcome various obstacles in order to stay in this place.”

Maurileno is a santeiro, a craftsman of saint and angel effigies. He learned the profession from his uncle and father, who were masters in the restoration of saints, churches, and other baroque and neoclassical buildings, such as the Our Lady of Grace Cathedral and Theatro da Paz. The painting and masonry work done by Maurileno’s family was also inculcated into Indigenous people who were molded into artisans in Jesuit workshops at Colégio Santo Alexandre in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Artist Maurileno Sanches, in Vila da Barca, has no doubts the housing project stalled due to real-estate speculation. Photo: Alessandro Falco/SUMAÚMA

Despite its stigma as an area of poverty and violence, Vila da Barca is home to young artists as well as college students, domestic workers, shopkeepers, fishers, and farmers’ market vendors. With the goal of teaching younger generations the skills he learned from his parents, along with sculpture techniques of his own creation, Maurileno offers workshops at facilities like Núcleo Curro Velho, not far from Vila da Barca. According to Maurileno, teaching children and young people art and culture has the power to transform a neighborhood and the lives of its residents. The urban projects developed for the climate summit, he argues, should invest in attracting tourists to places like Vila da Barca, with its wealth of traditions.

Belém’s historic market, Ver-O-Peso, features clogged sewer lines and rat infestations

Built 396 years ago, Ver-o-Peso will be completely renovated, according to the Mayor’s Office. Photos: Alessandro Falco/SUMAÚMA

Most of the remedial COP-30 projects announced to date will be financed by the federal government. In addition to plans to dredge the river and expand the international airport, public administrators have mentioned six other projects that will renovate historic sites and introduce new parks. On a visit to the capital of Pará on June 17, President Lula signed a document to launch work on São Joaquim Urban Park, budgeted at roughly USD 31 million. Funds will be provided by the Ministry of Cities, headed by Jader Barbalho Filho, brother to the governor and another member of the clan that has dominated Pará politics in recent years. Lula also signed a letter of intent regarding the proposed updates to Ver-o-Peso although, according to the Municipal Department of Urban Planning, the budget has yet to be defined.

“Ver-o-Peso is an iconic site here in Belém but looking at it, you’d think it was a favela,” said Osvaldina Ferreira, a cook in the market’s food sector, complaining about government disregard for Belém’s historic market. Osvaldina, 75, has worked at Ver-o-Peso for 35 years, supporting her household by selling fried fish, which she now does with the help of her daughters and granddaughters.

“Looking at it, you’d think Ver-o-Peso was a favela,” said Osvaldina Ferreira, a cook in the market’s food sector, complaining about government disregard for Belém’s historic market. Photo: Alessandro Falco/SUMAÚMA

Built 396 years ago, Ver-o-Peso will be completely renovated, according to the Mayor’s Office. In stark contrast to the images published when President Lula signed the protocol of intent, the market is currently in precarious shape. Ver-o-Peso begins at the Estação das Docas, where dock warehouses have been converted into a space for leisure, cultural activities, and restaurants, and extends to the pier district of Pedra do Peixe. Right after entering the facility, visitors have to dodge a steady stream of street vendors who crowd passageways in their struggle to eke out a living. Politicians, journalists, celebrities, and the city’s residents all proudly proclaim this diverse market as Latin America’s largest.

The entire Ver-O-Peso complex encompasses four fruit, vegetable, and fish markets, a group of refurbished warehouses, and an area of shops. Here, local residents, restaurants, and supermarkets can buy myriad forest products and a wide selection of fresh fish wholesale, shipped into the city through Guajará Bay. Ver-O-Peso also feeds a broader network of farmers’ markets and grocery stores in Belém and neighboring municipalities. Every day, dozens of bus lines bring in thousands of passengers from all over Greater Belém.

Rodents and insects, poor security and lighting, are now commonplace at Ver-o-Peso. In numerous areas, like the food sector—a popular spot with tourists who want a quick snack or some fried fish with açaí—vendors have taken it upon themselves to tackle such challenges as water leaks and clogged sewer lines.

“Generally speaking, people are outraged about the city government’s neglect in recent years. But we hope the renovations they’ve announced will involve dialogue, closer contact, and genuine interest,” said vendor Dalci Cardoso, 73, who for the last 30 years has sold leather sandals with rubber soles made from recycled tires.

“People are outraged […] but we hope the renovations they’ve announced will involve dialogue and genuine interest”, said 73-year-old vendor Dalci Cardoso. Photo: Alessandro Falco/SUMAÚMA

Mansions of various styles have been built over the centuries in the historic neighborhoods of Campina and Cidade Velha, bordering Ver-o-Peso. Many of the buildings are dilapidated, some have burned down, and still others have come to serve as warehouses of imported goods. Stripped of architectural memory, bigger pieces of land are turned into parking lots, as the city of Belém becomes more disfigured day by day.

A few minutes’ drive from these two neighborhoods sits Porto Futuro Urban Park, which the state government plans to expand in the direction of the waterfront. Once again, the city is adding new infrastructure that will benefit the neighborhoods of Umarizal and Telégrafo, known for their overvalued real estate and large residential towers, among the city’s most luxurious.

The hopes of those who defend culture, sometimes armed only with love

In historic downtown Belém, between the neighborhoods of Campina and Cidade Velha, stands Kamara Kó gallery, one of several cultural spaces in the region. Kamara Kó is run by cultural producer Makiko Akao and photographer and educator Miguel Chikaoka. Drawing inspiration from the Waiãpi people, the name means “true friends” or “brothers” in the Tupi language. Like Cidade Velha—Old Town—Belém’s historic city center is the site of private homes, churches, and other buildings, some dating to the 17th century. Certain areas are more residential while the less-affluent Bairro do Comércio—Commercial Neighborhood—holds a greater concentration of business establishments.

Miguel, a native of São Paulo, and Makiko, who was born in Japan, were active in the movement that earned Belém photography a position on the national cultural scene in the 1980s. Makiko was a co-creator of the project Circular Campina Cidade Velha, which seeks to bring visitors from Belém and beyond to dozens of cultural spaces located in the two historic neighborhoods. Makiko argues that if the creative economy received more incentives, the event, held every two months, could become part of the city’s permanent cultural and tourist map. Both would like to see summit preparations encourage this type of urban intervention to promote history and culture. “Better sidewalks, regular garbage collection, and good policing would be a big help in getting more visitors involved in the city’s creative economy,” Makiko said.

Down through history, scientists, intellectuals, and writers have celebrated this central part of Belém. “I want Belém the way people want a love. Belém has awakened in me an unimaginable love,” confided modernist author Mário de Andrade in a letter to poet Manuel Bandeira in May 1927, after passing through the city on a trip he took from Rio de Janeiro along the Brazilian coast. Bandeira found delight in the simple act of “savoring some cupuaçu or açaí ice cream” on the Parisian-styled terrace of the Grande Hotel, inaugurated in 1913 and then demolished under the orders of Coronel Alacid Nunes, appointed governor of Pará by the business-military dictatorship in the 1970s.

News about COP-30 has yet to reach environmental refugees

The island of Caratateua, seat of the district of Outeiro, lies outside the COP-30 Polygon, about 20 miles from Belém’s historic center. Jhonny Rivas and Mariluz Nunez, an Indigenous couple of the Warao people, say their view of the river reminds them of their homeland, where they lived in stilt houses. Today they reside in a community along Avenida Beira-Mar, in the neighborhood of São João do Outeiro. People from the ethnic group Warao, which means “people of the waters,” began migrating to Brazil from Venezuela in 2014; today, around 600 live in Belém, with another 200 residing elsewhere in the metropolitan region.

Indigenous Jhonny Rivas and his family (photo) of the Warao people are environmental refugees. They live in a dirt-road community without access to sewers. Photo: Alessandro Falco/SUMAÚMA

The island can be reached by water or by the Augusto Montenegro highway. In 1975, the city began expanding inland along this road, first with government-financed housing projects and land occupations known as “invasions” and later with the construction of private condominiums and other types of buildings. Today, shopping centers, churches, government offices, and the Mangueirão soccer stadium line Augusto Montenegro highway.

The unpermitted wooden houses built in the dirt-road community occupied by Jhonny’s paternal family have no direct access to water or sewer. In his native country, Jhonny, who is from a family of fishers, tried to make it as a professional soccer player. Mariluz, her father a nurse and mother a midwife for the community of Jotajana, used to work as a cleaner in a doctor’s office. Of the many people comprising the twenty-five nucleuses of this extended family, few speak Portuguese or Spanish, which hinders their access to information about what is happening in the city—like the fact that Belém will host COP-30.

Anthropologist Rosa Acevedo-Marin is one of the coordinators of the project New Social Mapping of the Amazon. Her research indicates that Indigenous peoples in the Venezuelan state of Delta Amacuro have been driven off their land—much like the couple and their family—due to disputes with corporations and projects intent on exploiting oil, gas, and minerals. The economic policies of the Venezuelan government have incentivized these activities since the 1960s.

Caratateua Island lies outside the COP-30 Polygon, in the Outeiro district, about 20 miles from Belém’s oldest center. Photo: Alessandro Falco/SUMAÚMA

Before moving to the capital of Pará, Jhonny and Mariluz tried life in the cities of Boa Vista and Pacaraima, in Roraima state, which shares a border with Venezuela. They later traveled by boat from Manaus to Belém, arriving penniless and hungry, with their two small children. Two weeks later, they headed to Fortaleza, capital of the Northeastern state of Ceará, where Mariluz gave birth to her third child, a girl. The family left Fortaleza to return to Belém, and then moved again, this time to the municipality of Redenção, in southeastern Pará. There, Jhonny suffered threats from xenophobes, who in one instance even pointed a gun at him. This episode prompted the couple’s return to Belém.

Back in Belém in 2020, they enrolled their kids in school. But the family’s children, like many others, have trouble in class because they aren’t fluent in Portuguese or Spanish. Without any teachers who speak Warao or any interpreters of the language, children find it challenging to adapt and learn.

After living through a period of homelessness—“very bad,” says Jhonny—Mariluz feels protected in her house, which she, like others in the community, rarely leaves. Mariluz says that in Brazil, Warao women are often sexually harassed by men, who commit obscene acts like exposing themselves to these women in public. “Thank heavens, we feel relaxed in our homes now,” says Mariluz, who occasionally goes to Ver-o-Peso to buy the materials Warao families use to make necklaces, bracelets, and other colorful adornments in shapes such as butterflies and caimans.

Caratateua Island: there’s nowhere to raise produce like potatoes and cassava; life here is more expensive and more grueling. Photo: Alessandro Falco/SUMAÚMA

Mariluz, who has a bachelor’s degree in science, is one of the few in the group who can read and write. In addition to fighting for the children’s access to public schools, she also takes part in efforts to secure rights for Indigenous refugees. While these Warao families don’t talk about topics like the climate and environment in the community where they live, they know full well how important land and water are to food and health. Their experiences as a vulnerable population compel them to speak about the exoduses caused by mega-agricultural and mining projects across Pan-Amazonia.

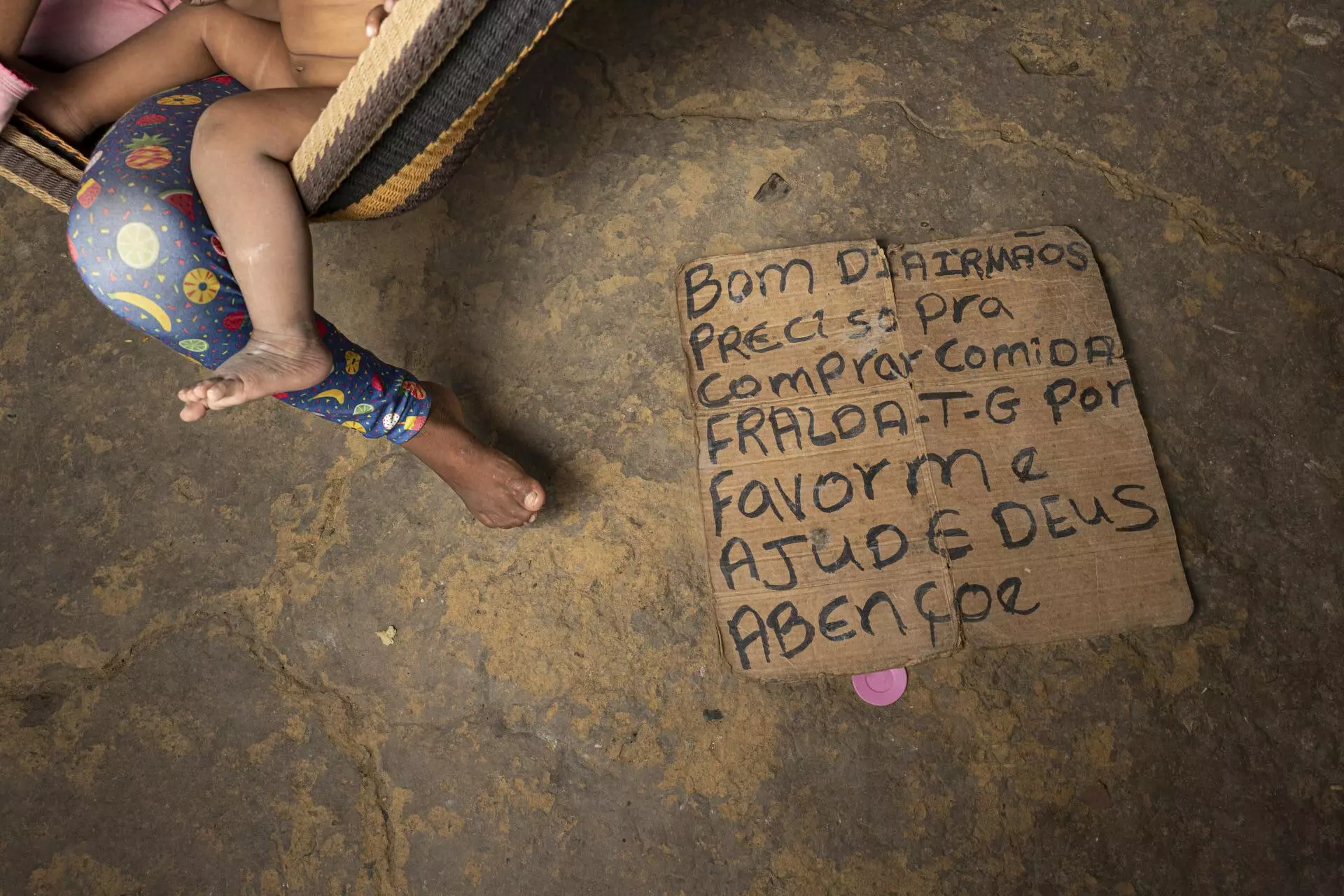

Life is also more expensive and their diet more limited because they have nowhere to raise produce like potatoes and cassava. “As Indigenous people, we’re all suffering. How are we going to eat without any money? How are we going to support our children without work?” asks Mariluz. For those whose fates rest most heavily on the contracts that will be signed in the comfort of air-conditioned spaces, “COP-30” is yet another term in a language they don’t understand.

President Lula at the event that officialized Belém as the host of COP-30 in 2025. Photo: Alessandro Falco/SUMAÚMA

Unless preparations for COP-30 foster a broad debate, the event may be all style, no substance

The politicians involved in the planning stages of the climate summit guarantee that the proposed renovation works will leave a legacy—much as Brazil was promised in the runup to the World Cup in 2014 and the Olympics in 2016. Yet both events left a trail of corruption, with many families evicted from their homes to make way for new stadiums and other infrastructure works. When SUMAÚMA asked the Belém Mayor’s Office about the funds and jobs these new projects are expected to generate, officials said “the figures haven’t been defined as yet and, for now, the federal, state, and municipal governments are selecting and designing the works that will be needed to get the city ready to hold the event.”

According to the city, the price tag for just the four projects announced shortly after the United Nations selected Belém to host COP-30 is nearly USD 166 million, a sum that will be funded by different sources, including the mining titan Vale. “This set of new works will have an immediate effect on the generation of jobs in the construction sector, for example, and indirectly among those providing services to the companies leading the works,” said Luiz Araújo, municipal secretary of Control, Integrity, and Transparency.

For the past 25 years, Saint-Clair Cordeiro da Trindade Júnior, full professor at the Universidade Federal do Pará and a specialist in human geography and urban policy, has studied Belém’s transformation into a metropolis, a process that began in the 1990s with major urban interventions to the downtown area. He insists that COP-30 projects will have to be based on an integrated vision and have a positive impact on other policies, such as housing and mobility.

Urban interventions driven by major events tend to overlook land use by the general public and instead are “designed as tourist attractions and enticements for economic investments” that fail to take into account “the daily relationships of life and its territories.” Without social investments, Saint-Clair warns, the tourism sector cannot grow. Local residents need to enjoy the city, he points out. “You have to consider the spaces people use in their daily lives, so those living here don’t need to pay for access to everything [in these spaces].”

Lika, who formerly worked at the Aurá garbage dump, now has a job decorating birthday and graduation parties. She is also taking courses with other women on how to run a thrift shop in cooperation with her colleagues. She was already an adult when she went on an excursion organized by the NGO Pará Solidário and ate in a restaurant, visited a shopping center, and saw the sites of Belém for the very first time. Neither Lika nor any of the other women who are fighting for a life with less garbage—where people aren’t treated like trash—are allowed into discussions about the environment or the Right to the City concept. But they should—if not, all a climate summit in the urban Amazon will do is greenwash the image of local politicians and transnational corporations.

Fact check: Plínio Lopes

Spell check (Portuguese): Elvira Gago

Translation into Spanish: Julieta Sueldo Boedo

English translation: Julia Sanches and Diane Whitty

Photography editing: Marcelo Aguilar, Mariana Greif and Pablo Albarenga

Page setup: Érica Saboya

At low tide, boats from all over the country crowd the back of Ver-o-Peso market, in Belém do Pará. Photo: Alessandro Falco / SUMAÚMA