There was an almost gangster-ish menace in the response of retired Army colonel Gelio Augusto Barbosa Fregapani when a journalist asked him about an attack on nine indigenous people in the State of Roraima. The military man fiercely rebutted accusations that he organized the resistance of local farmers to what would become the Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous Territory, but then boasted he would have gone further if he were truly in charge.

“If I had taught guerrilla tactics, there wouldn’t have been a single federal cop there. And whoever said this would be dead,” the colonel told a reporter in an interview with Folha de S.Paulo in 2008 after Federal Police had said there were signs that he had helped to draw up a strategy to keep the large landowners from being expelled from the territory. Fregapani, then aged 72, then went even further with a threat: “Once the region declares its independence, then indeed I will assemble guerrillas.”

Retired Colonel Gelio Fregapani (center) sees Raposa Serra do Sol’s demarcation as an attack on national sovereignty. Photo: Reproduction/Cigs Website

In the colonel’s view, the continued demarcation of the Raposa Serra do Sol territory – which had just been done – meant making the “region independent” because it is on the border with Venezuela. Raposa Serra do Sol is the traditional territory of the Ingarikó, Macuxi, Patamona, Taurepang, and Wapichana peoples. Over 26,000 Indigenous people live there according to their cultural traditions, on 1,75 million hectares, an area around 11 times the size of the city of São Paulo. The pristine nature in the Indigenous Territory helps the Amazon Rainforest stabilize the planet’s climate.

Most members of Brazil’s military, however, see Raposa Serra do Sol as an attack on national sovereignty. “Everything indicates that environmental and Indigenist problems are just pretexts. That the main NGOs are actually pieces of the big game where hegemonic countries strive to maintain and expand their domination.” This isn’t a quote from Aldo Rebelo or some other conspiracy theorist on social media. It comes from a 2005 intelligence report issued by the Brazilian Intelligence Agency, Abin. Signed by Fregapani himself, it was published in the pages of another major Brazilian newspaper, Estado de S. Paulo, which in 2005 reported that demarcation of the Indigenous Territory could “create conflict with the Armed Forces.”

The Abin of 2024 denies this. Using the Access to Information Act, SUMAÚMA asked the agency for all of its intelligence reports on Raposa Serra do Sol produced in 2005. Fregapani’s report was not included in the batch sent. “The supposed report is not contained among the intelligence documents produced by Abin in 2005 regarding the topic of the Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous Territory’s demarcation,” Abin responded, this time via its press representative. “The Agency notes that the simple mention of the fact that it was allegedly signed is itself proof that such a document, if it exists, is not an Abin-produced document. That is because this is not (and was not, at the time) the standard for Intelligence Agency products.”

Attacks against the Indigenous people in Raposa Serra do Sol have wounded many people, like Izabel Macuxi’s brother. Photo: Sérgio Lima/Folhapress

Nevertheless, one of Abin’s own press releases, from 2005, contains more information: “The aforementioned document was produced by the Amazon Working Group, an informal panel comprised of members of the Abin and of Armed Forces and Federal Police Department intelligence agencies, which work toward systematizing Intelligence activities in the region and equalizing knowledge.” The release, archived on the Instituto Socioambiental website, also says the report is the “result of a consensus among members of the Amazon Working Group, discussing among other matters the Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous Territory and signed by its coordinator and Abin representative, Gelio Fregapani.”

Not only was he a career Army official, but Fregapani was part of the “information community,” as its members call themselves. Abin refused to share, via the Access to Information Act or its press representative, whether the colonel was on staff. Yet Fregapani himself says on his social media that he worked at Abin from 1996 to 2007 – in other words, up to one year before he was suspected of having armed anti-Indigenous guerrillas. He even served as the agency’s regional superintendent in Roraima.

The case of Gelio Fregapani is extreme, yet it exemplifies how a profoundly ideological view of the Amazon took root in Brazil’s Armed Forces – particularly in the Army, its largest and most politically influential branch. This view is at the root of initiatives like the National Integration Program, run by the business-military dictatorship from 1964 to 1985, which massacred Indigenous people to open roadways and bring “men without land to lands without men.” It also created a destructive and impoverishing occupation of the region, as seen in the state of Pará in cities like Altamira, Medicilândia, Itaituba, and Novo Progresso. It is moreover part of a framework of events that led the military to conspire to impeach Dilma Rousseff in 2016. This ideology is also characteristic of the generals who were influential in the far-right Jair Bolsonaro (Liberal Party) administration. And finally, it shows up in the visible ill will from the Armed Forces about engaging in the fight against the Yanomami genocide.

The illegal mining defended by influential members of the military has brought genocide to the Yanomami Indigenous Territory, with children in particular dying. Photo: Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

To understand how this ideology emerged and infiltrated military thinking, you have to go back to the 1950s.

In the heart of General Villas Bôas

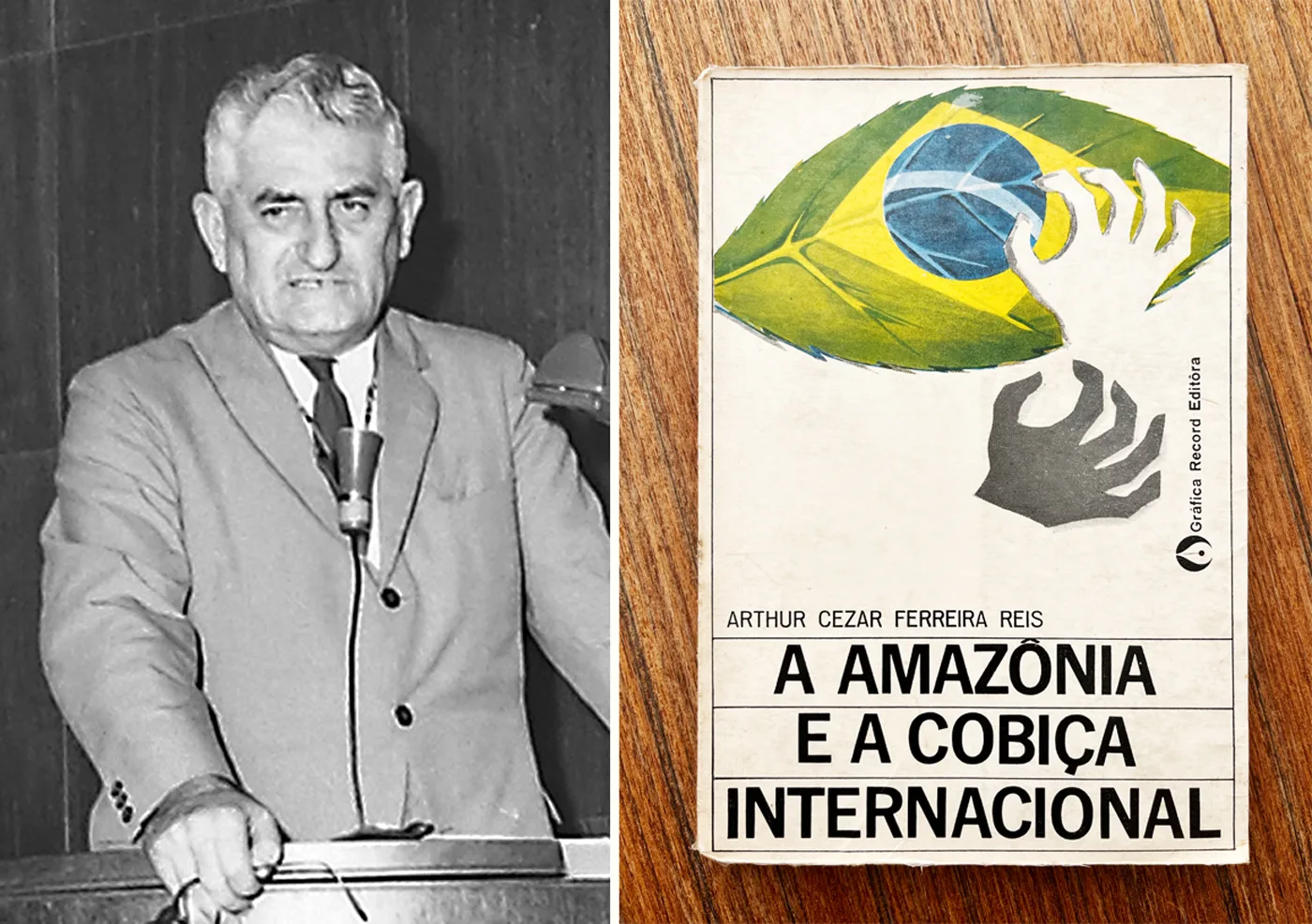

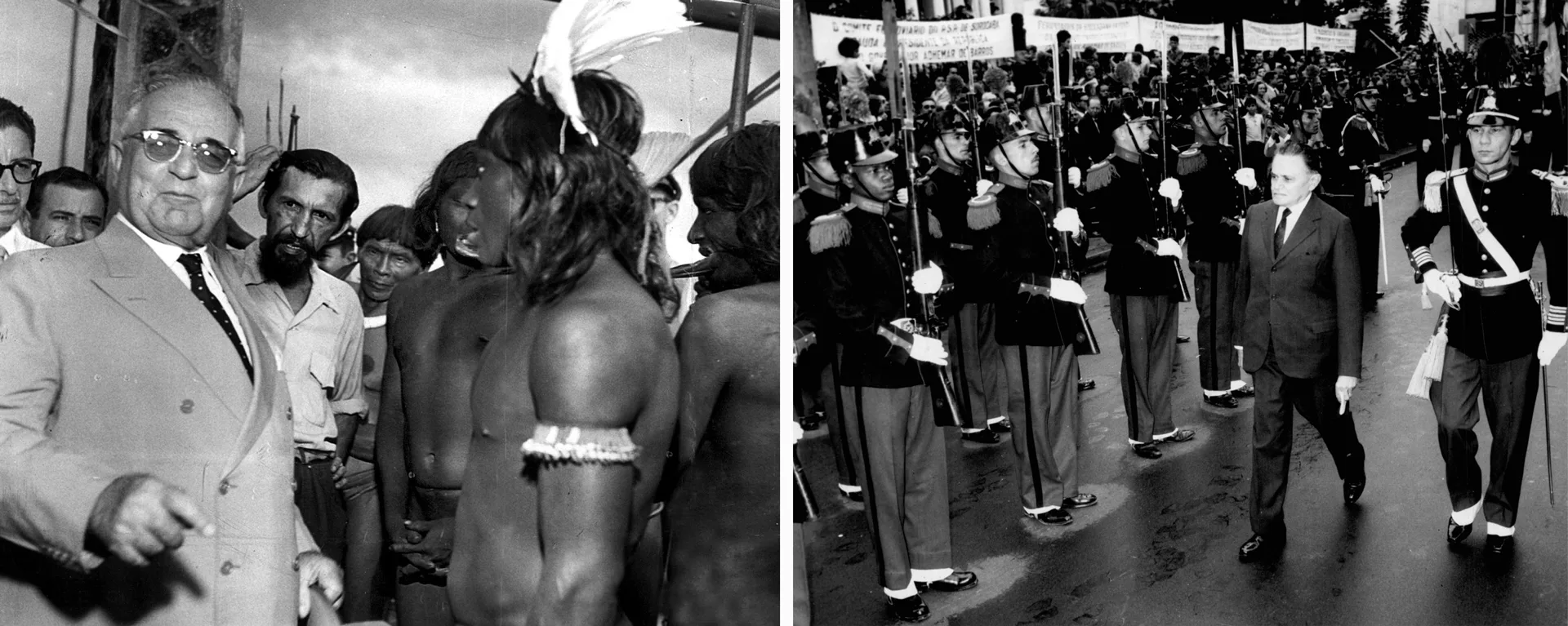

Amazonian Arthur Cézar Ferreira Reis was already a political veteran – he had participated in the Revolution of 1930 and in the conservative administrations of President Eurico Gaspar Dutra (1946 to 1947) and São Paulo governor Ademar de Barros (1948) – when Getúlio Vargas called him in 1951 to join the group that would create the Office of the Superintendent of the Economic Valorization Plan of the Amazon. He ran the agency from 1953 to 1955, when he left to head the National Amazon Research Institute, another government-owned enterprise.

What really obsessed Reis, however, was calling attention to what he said was an “attempt to internationalize the Amazon Forest.” This was the subject of a book he wrote, titled A Amazônia e a Cobiça Internacional (loosely translated, The Amazon and International Greed). His decision to start writing it likely came from an event that happened 13 years earlier, in 1947: an attempt to create a multinational body that was to be called the International Institute of the Hylean Amazon. Supported by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, or Unesco, it was supposed to be a center headquartered in Manaus for research in areas like botany and zoology, with the countries and territories that held the Amazon participating – Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela, France (French Guiana), the United Kingdom (Guyana), and the Netherlands (Suriname). An agreement, the Iquitos Convention, was even signed by some of these countries in 1948. Yet the Institute never reached fruition because of nationalist opposition in several of these nations – including Brazil.

Arthur Reis’s book on alleged international interests in the Amazon has already had six print runs. Photos: National Archives of Brazil and SUMAÚMA

“In Europe, the Convention had been welcomed as an opportunity to expand capital and populations. This is the information we have,” Artur Reis writes in his book. “The Amazon is being considered as the ideal open space for receiving populational surpluses (…), producing the food needed by those masses punished by pitiless and deadly hunger, and producing the plant, animal, and mineral raw materials that the world’s large industrial parks lack,” the text predicts. Ironically, the production of raw materials is now an activity largely explored by cattle ranchers, soybean farmers, and large transnational mining companies, who arrived in the region with the dictatorship’s encouragement.

Reis reaches an apocalyptic conclusion: “The Amazon is in the crosshairs of international bodies, who see it as a space available for the future. This is an incontestable truth. I don’t want to hear any reference to other regions in the world that have also yet to be occupied. They are much smaller and belong to countries where it is impossible to proceed with the audacity intended in relation to Brazil.” The book made an impact – it had five print runs from 1960 to 1982.

It may be that Reis’s vision of the Amazon was what influenced Marshall Castello Branco, the first military dictator after the coup of 1964, to choose him as the governor of Amazonas. The dictatorship had impeached Reis’s predecessor, a politician affiliated with deposed president João Goulart’s Brazilian Labor Party. It is true that Reis’s work remains popular among very influential members of the military. General Eduardo Villas Bôas, the Army’s commander from 2015 to 2019 and a decisive actor in recent episodes in Brazilian public life, created an eponymous institute after he had to become a reservist. One of the projects he promises to execute “soon” is a reissue of A Amazônia e a Cobiça Internacional, as part of a book collection entitled “Thinkers of Brazil.”

Ferreira Reis worked for several administrations, including Getúlio Vargas (left), and his ideology permeated the military dictatorship starting with its first leader, Castelo Branco (right). Photos: UH/Folhapress Collection

It is worth stopping for a second to look at Villas Bôas. Appointed the Army’s general-commander by Dilma Rousseff (Workers’ Party), he and his right-hand man, General Sérgio Etchegoyen, the Army’s Chief of Staff, conspired to impeach the president. That is according to Michel Temer (Brazilian Democratic Movement), the vice president who became president. He says this in a memoir written by his friend, the philosopher Denis Rosenfield. Temer reports “various conversations” with the heads of the Army, where they both asked him for opinions on “scenarios with which to work.” Their ties grew from the wear on the relationship between the Workers’ Party and the military that began with the demarcation of Raposa Serra do Sol, deepening after the election of Dilma (seen as a “terrorist” by the dictatorship’s disciples) and her decision to create the National Truth Commission. This “was a knife in the back,” Villas Bôas would say in a long interview with anthropologist Celso Castro that became a memoir. Set up to investigate the crimes during the dictatorship, the Truth Commission’s final report mentioned Etchegoyen’s father and uncle. The sons of Army officials, Etchegoyen and Villas Bôas run in the same circles and have been friends since their were young boys in Cruz Alta, Rio Grande do Sul. After Temer (Brazilian Democratic Movement) was sworn in, Villas Bôas continued to run the Army, while Etchegoyen went to the Palácio do Planalto to lead the re-created Institutional Security Bureau.

Villas Bôas also worked to open the way for Jair Bolsonaro’s election. On social media, he made a clear threat to the Federal Supreme Court on the eve of a habeas corpus ruling that would have given Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva a chance to dispute the 2018 election. “In this situation Brazil is experiencing, all that’s left is to ask the institutions and the people who is really thinking about the good of the country and the future generations and who is just worried about personal interests?” he shot off on Twitter, on the night of April 3 of that year. “I assure the Nation that the Brazilian Army feels it is sharing the wishes that all good citizens have to repudiate impunity and to respect the Constitution, social peace, and Democracy, while also remaining aware of their institutional missions,” he wrote. Two days later, the Supreme Court denied Lula the ruling that could have kept him out of prison and in the campaign. In his memoir, Villas Bôas admitted the posts were dialed down – but approved – by the Army’s entire High Command (the group of active four-star generals, at the top of the chain).

With Bolsonaro elected, the now-retired general was given a government position. He was not alone: Augusto Heleno became a minister. What they both have in common is that they were military commanders in the Amazon, or rather, they ran all of the Army’s units located in the rainforest. This was the position Heleno held when he took a shot at the Lula administration’s policy on Indigenous people, in 2008: “It is completely separate from the historical process of our country’s colonization. It’s regrettable, not to say chaotic.” The phrase had a target: Raposa Serra do Sol’s demarcation.

General Eduardo Villas Bôas, one of Bolsonaro’s advisers, organized seminars to discuss Brazil and the Amazon. Foto: Gabriela Biló/Folhapress

Going back to 2021, the Villas Bôas Institute organized seminars discussing Brazil where the Amazon was a constant topic. These meetings gathered recognized representatives of Brazilian climate denialism, including Aldo Rebelo, who served as Dilma Rousseff’s defense minister from 2015 to 2016, a time when he was affiliated with the Communist Party of Brazil; he is currently with the Brazilian Democratic Movement and tried to run as the deputy mayor candidate as part of a Bolsonaroist slate in São Paulo. They also included meteorologist Luiz Carlos Molion and the then-head of Embrapa Territorial, Evaristo Miranda, who became two of the favorite scientists of the far right and Brazil’s large landowners, owing to their denial of all evidence that we are experiencing a climate emergency. Other participants were Ricardo Salles, at the time Bolsonaro’s former environment minister, and General Augusto Heleno. They spoke at symposiums mediated by journalist Alexandre Garcia, formerly a TV Globo commentator, a former aide to João Figueiredo (the last military dictator), and currently a columnist on extreme-right websites publishing news and disinformation.

At the end of one of these events, Villas Bôas published a closing message: “Friends who with us have suffered the indignation of seeing our country being appropriated – the big advantage that environmentalism and Indigenism enjoy, and the disinformation dishonestly amplified by the spreading of falsehoods and distortions. Our purpose is to restrain this world of disinformation. Our speakers, free of ideologies, use scientific grounds or knowledge of reality as bases, factors to which public opinion has no access.”

The Trans-Amazonian Highway’s construction (left) marks the start of the forest’s destruction, which years later is facing historic droughts like the one on the Solimões River (right). Photos: Folhapress and Michael Dantas/SUMAÚMA

SUMAÚMA asked Villas Bôas for comment, sending e-mail messages to the institute bearing his name and to his cell phone, which is currently being answered by his wife and daughters. We received no response. Calls to the mobile phone and landline listed on the institute’s website were not answered.

We also contacted Augusto Heleno. One of his former aides at the Institutional Security Bureau said the general “is not granting interviews.” We asked him to forward some questions to Heleno, to which he said he “would try.” A mobile phone number we called and an old e-mail address we sent a message to are no longer active.

The dictatorship’s ideologies

“In the 1960s, General Golbery reformulated the major geopolitical maneuver of national integration. He recommended that, starting from the shared base of our continental projection (the region around the Rio-São Paulo-Belo Horizonte triangle), we would accelerate integration of same [sic] into the ‘central platform’ and, hence, we would inundate the Hylean Amazon. This is the strategic maneuver of the Central Plateau front, moving full steam ahead.” Golbery do Couto e Silva, also known by “Corcunda” or “Corca” by his adversaries in the barracks, worked in the Army’s information community at the same time he was conspiring with the 1964 coup mongers. With the dictatorship implemented, he became a cornerstone of three of its five administrations – including the first, the Castello Branco administration. Those who study the Armed Forces see him as one of the great formulators of the Army’s geopolitics.

General Golbery do Couto e Silva was responsible for reformulating the national integration policy in the 1960s. Photo: Moreira Mariz/Folhapress

Another is General Carlos de Meira Mattos. The quote about Golbery in the paragraph above was taken from Uma Geopolítica Pan-Amazônica (A Pan-Amazonian Geopolitics), a book Meira Mattos published through the Army Library in 1979. It is a tribute to the book Artur Reis wrote nearly 20 years earlier. Meira Mattos proposes an “Amazonian Cooperation Treaty” among the biome’s countries where “to achieve full development […] it is necessary to maintain the balance between economic growth and environmental preservation.” Yet it celebrates the building of roads as “the bones of our Amazon conquest strategy,” the crown of which is “the great crossing, cutting across ridgelines from east to west, and connecting the longitudinal arteries that followed these dividing lines between them – the Trans-Amazonian Highway.” Today, these highways are recognized as vectors of deforestation and social inequality in the region, in addition to having caused the extermination of Indigenous people.

Meira Mattos remained convinced that he was right. In 2006, he wrote a paper for the Army’s Revista da Escola Superior de Guerra journal where he attacked “the propaganda and the international pressures favoring this thesis of internationalization dressed in pseudo-scientific fallacies” whose “main propagandists are the international non-governmental organizations of the rich countries in Europe and the United States, present and active in the Brazilian Amazon through their agencies and religious missions, with ample money available and involving participation by Brazilians.” He took the opportunity to defend the North Channel project, the military’s most recent name for occupying the region, launched in 1985, after the dictatorship fell.

Meira Mattos died one year after his paper was published, in 2007. His reputation nevertheless remains intact among his peers: his name graces one of the main departments in the Army Command and General Staff School. Going through the school is a must for officials who want to reach the top of their career: it prepares them “to exercise the roles of General Staff, Command, Leadership, Direction, and Advising at the highest echelons”. The Meira Mattos Institute is aimed at “connecting the [Army School] with the academic environment and strategic study centers inside and outside the country and at the conduction of studies, events, and strategic study trips.”

General Carlos Meira Mattos saw the roads opened by the dictatorship as ‘the bones of Amazon conquest.’ Photo: Folhapress

A complete failure

João Roberto Martins Filho, a senior associate professor at the Federal University of São Carlos, is among Brazil’s longest-running academic researchers of the Armed Forces. He was also the first president of the Brazilian Association of Defense Studies, created in 2005, and is a researcher at several foreign universities. He told SUMAÚMA this view of the Amazon is a point where members of the Brazilian military converge.

“The idea of protecting the Amazon [from foreign greed] is one of the big unifying factors in Army ideology. This comes from the 1950s, it grew stronger in the 1960s and 1970s, during the dictatorship,” says Martins Filho. He cites one example as evidence of this – military leaders jointly defending General Augusto Heleno in 2019, after he said critics of Jair Bolsonaro’s environmental policy should “find their own crowd.” This phrase was uttered the night before a meeting of the world’s 20 richest countries and after criticizing the German chancellor at the time, Angela Merkel, and France’s president, Emmanuel Macron.

Weeks later, a debate in Brasília brought the Bolsonaro-aligned Eduardo Villas Bôas and Army Reserve General Alberto Cardoso together to discuss this topic. Both were unified in seeing an unfair attack against Brazil. While Villas Bôas’s position came as no surprise, Cardoso’s was very much a surprise. “He was the head of the [institution that later became the Institutional Security Bureau] during the Fernando Henrique Cardoso (PSDB) administration and he was regarded as an intellectual. But it was at that debate I noticed they were all united [on the topic],” recalls Professor Martins Filho. The Correio Braziliense reported at the time that General Cardoso had commented that criticism about “invasion of Indigenous Territories, agribusiness, mining, environment” were “instruments of fixation, of attacks on the Brazilian State. There is a strong, external maneuver in this here, and internal too.”

The military’s view that the Amazon needs to be productive has persisted since the dictatorship. General Augusto Heleno, a member of the Bolsonaro administration, has emphatically opposed the Raposa Serra do Sol territory. Photos: Lela Beltrão/SUMAÚMA and Carolina Antunes/PR

While still a university student, in the mid-1970s, Martins Filho traveled to the Amazon by bus and boat to see what Meira Mattos called “the bones of the Amazon conquest strategy.” He says “the [dictatorship’s] colonization project was a complete failure. […] People were getting on and off the bus the entire time, and everyone was telling the same story: ‘I came here, I had no support whatsoever, I caught malaria, it was a disaster, it didn’t work out.’”

Nevertheless, the roads the dictatorship ripped open became a pathway to deforestation. Cities sprang up and grew along their edges. Some became hubs of wealth, thanks to large landholdings that killed the forest to make way for soybeans or for immense herds of beef cattle. Yet what abounds in most of them is social inequality and violence. Organized crime from the big cities in Brazil’s southeast invaded the region and took over several areas being illegally mined – operations to which the military usually turns a blind eye.

None of this has caused the military to reassess its view of the Amazon, says Martins Filho. “Modernization would be understanding the environmental problem is real and can turn against Brazil. Yet the view remains the same: we’re the ones who discovered the Amazon, most of the capital cities started as forts, and nobody knows it like we do. The Amazon holds no secrets for us,” he explains.

Indigenous Territories as ‘Balkans’

“The military’s worldview of Indigenous peoples and the Amazon hasn’t changed since the dictatorship. And there is a turning point in it, which is the demarcation of the Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous Territory,” says Adriana Marques, a professor with the International Relations and Defense Institute at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. “It’s when General Augusto Heleno takes an emphatic stance in opposition [to demarcation] and a sharper critique of governmental policies [for the region] emerges.”

Adriana’s thesis upon completion of her doctorate at the University of São Paulo in 2007 was entitled “Amazônia: Pensamento e Presença Militar” (loosely translated, Amazonia: Military Thinking and Presence). It is a magnificent read for anyone who wants to understand how the strategic priority the military set for the region goes beyond a defensive strategy and touches on what she classifies as a tangled relationship between interests and symbolic elements.

“The military discourse sees its action in the Amazon as a continuation of the role played by Portuguese colonizers in the region. This shows that members of Brazil’s military do not identify the Portuguese colonizer as being diametrically opposed to them, (…) rather this colonizer is reverenced as their predecessor,” she writes. In another passage, the UFRJ professor writes “the region is not seen as demographically empty merely because it is not populated in the strict sense of the word, but because it is mainly populated by Indigenous communities.” In this sense, she continues, it is about being “empty of a population committed to preserving Brazilian sovereignty regarding the region. The perception that the Indigenous peoples living in the Amazon can be coopted by foreigners is a constant in military discourse.”

The professor also examines papers written by officials preparing to reach the top of their careers through classes at the Army Command and General Staff School. “Terms like Balkanization and even Mexicanization of the Amazon are recurrent in dissertations,” she says. There is a comparison between Europe’s Balkans – the scene of wars and geopolitical instability – and Indigenous Territories. To the military, they “represented a threat to Brazil’s territorial integrity, not just because they could be converted into ‘ethnic enclaves,’ but mostly because the process of creating reserves would be orchestrated by foreigners who would, at a later stage, use them as a pretext for military intervention in the Amazon.” Put another way, the professor continues, “the Army’s members did not recognize demarcation as a result of the Indigenous peoples’ fight to recover their lands. In the Castronian view, the Indigenous people would be instruments of malicious foreigners, and not subjects of their own claims.”

Brazil’s Indigenous people continue to fight to assert their rights 36 years after the Constitution’s enactment. Photo: Carl de Souza/AFP

Anthropologist Piero Leirner, an associate professor at the Federal University of São Carlos, has been researching the military for nearly 30 years. He sees the end of the Cold War between the USA and the former Soviet Union in the early 1990s – with the threat of communism being thus theoretically extinguished – as the moment when the military took a heightened interest in the Amazon. “That was when they did indeed adhere to the thesis of international greed, when the Earth Summit was held [the United Nations’ second summit on the climate and environment in 1992 in Rio de Janeiro]. And they began to formulate the North Channel as not just border protection, but as a military enclave, a militarized administration zone [in the Amazon]. They [the military] are the main hub of governability in the region.”

Another researcher, social scientist Guilherme Lemos, says: “Research indicates the Amazon became central to the military. Agendas like demarcating Indigenous Territories or fighting deforestation are seen as strategies for hiding international interest in this region’s wealth, both mineral and natural. This is the backbone [of military thinking on the Amazon]. And it is much more than the view of a general here, a colonel there: it is the Force’s institutional view.” Lemos is writing a master’s dissertation at the Federal University of São Carlos about Raposa Serra do Sol and the military presence in the region. His adviser is Leirner.

This is the type of thing that General Maynard de Santa Rosa, another shaper of the Army’s geopolitics, usually says. The website of the Sagres Institute, a military organization, contains an article where Santa Rosa says the following: “Oddly, a custom was instituted in Brazil of creating Indigenous and Quilombola reserves, based on questionable ethnological arguments, and in general with no historical backing, creating problems, including along the border zone. The Chinese resolved the issue of sovereignty over remote areas of Tibet and Sinkiang [Xinjiang] through a policy of massive investment in transport infrastructure and mass migrations of ethnic Han people, ousting the local Tibetan and Uygur populations.” General Santa Rosa is now better remembered for his time serving under Jair Bolsonaro (2019-2022) as the president’s Strategic Affairs secretary, from January to November 2019.

The “Chinese solution to the question of sovereignty” to which the general refers was seen by the international community as having violated the rights of minority populations. The European Union, United Kingdom, U.S.A., and Canada imposed sanctions on Beijing because of the mass incarceration of Muslim Uygurs. In what China calls “reeducation camps” there are reports of torture, forced labor, and sexual abuse. Nothing that would keep Santa Rosa from using the case to justify plans for massive construction projects in the Amazon, including at official events while serving in the government, as reported at the time by the Intercept. The general is paid the Army’s highest pension, at the rank of a marshal.

The Amazon has become a focus for military men like General Maynard de Santa Rosa, who formulated the Army geopolitics. Photo: Pablo Valadares/Brazil’s Chamber of Deputies

SUMAÚMA sent a question to Santa Rosa about this. “I did not propose the Chinese solution to the Amazonian problem, I just mentioned it as an example of how the Chinese resolved related centuries-old problems,” he answered in writing. “Our problem comes from an unfamiliarity with the region, while people that are familiar with it take the opportunity to implement their own interests. The environmentalist NGOs [non-governmental organizations] were created as a strategic instrument to be able to work freely in the territories of sovereign countries to benefit the global financial oligarchy,” he says. According to the retired general, starting with the 1988 Constitution “the State lost the legal ability to interfere with NGOs [and] the National Security Council was eliminated, which had held veto power over developments in areas like the Border Zone. The result was the indiscriminate multiplication of environmental, Indigenous, and Quilombola reserves that prevent exploration of natural resources and regional development.” Santa Rosa underscores that his opinion “is not necessarily the Army’s” and that he has “personal convictions [resulting from] ten years of service in different military units in the region and studies undertaken on my own.”

‘The Indians [sic] like the miners’

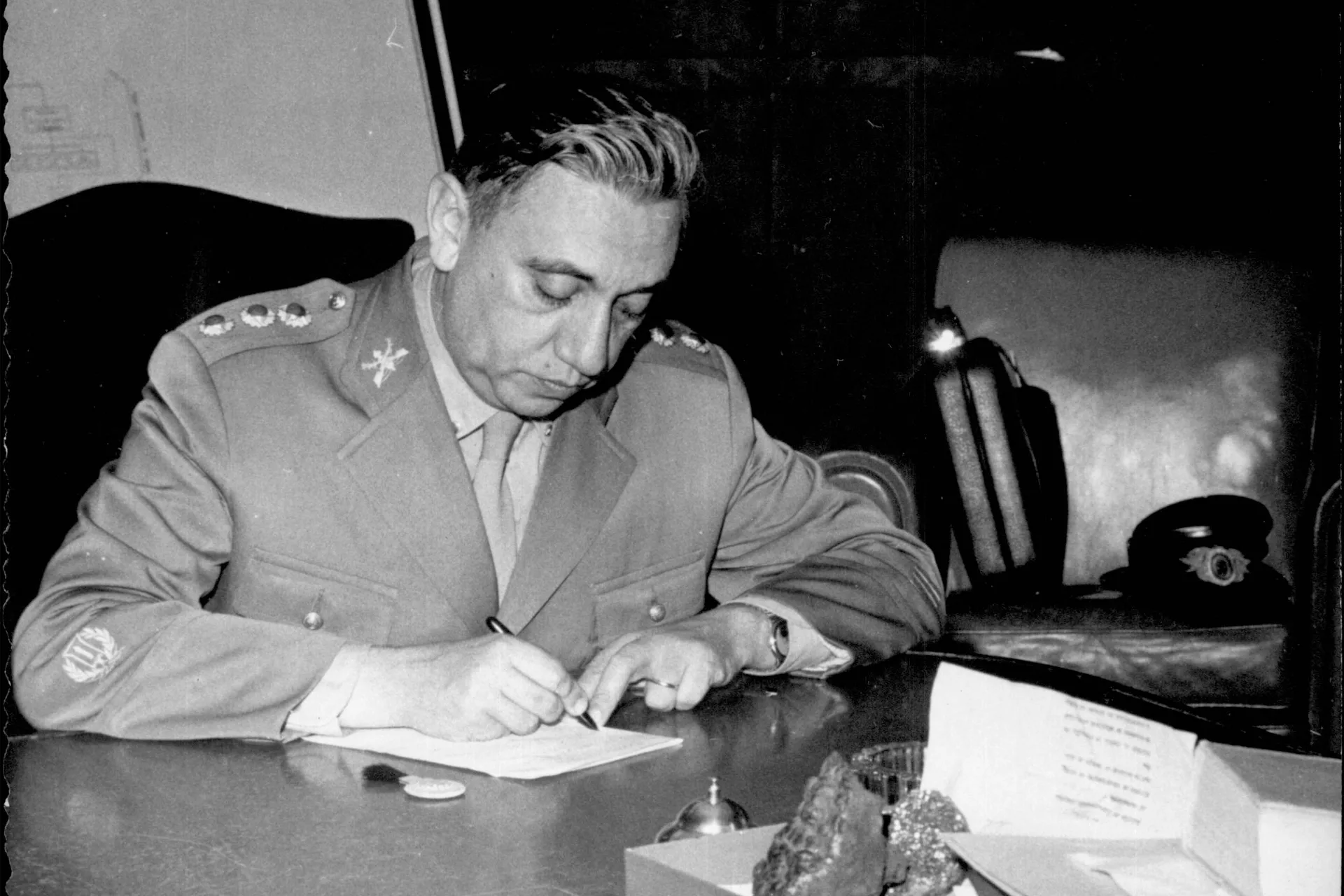

In 1995, the Army Library published A Farsa Ianomâmi (The Yanomami Farce), written by a colonel named Carlos Alberto Menna Barreto. On the cover, a white man with light hair, presumably European, removes a mask that has allowed him to pass for an Indigenous man. The book can be read through this image: prejudice against the demarcation of the Yanomami Indigenous Territory is packaged as nationalism: “If the Brazilian government’s indifference persists, soon they will have established another territory there of independent tribes, as a first step in a new Pirara [dispute] and in the definitive loss of that ‘land of wealth and delights’ that Brazilians call Roraima.” The book was published with public funds: the Army Library, better known as the Bibliex, is the ground force’s publishing house, which defines itself as “a centuries-old cultural institution of the Brazilian Army that contributes to the provision, publishing, and diffusion of bibliographic resources necessary for the development and enhancement of military-professional and general culture.”

Praise is given to General Carlos de Meira Mattos in the introduction: “There is a hidden intent behind all of this – internationalization of the Amazon. […] The author, taking offense as a Brazilian patriot, responsible for protecting our sovereignty in that border region, wrote a passionate account. He lets out his scream of protest […] against the farce that has been built around the Yanomami issue.” The book was recommended several times by Olavo de Carvalho, a self-declared philosopher and ideologue on Brazil’s extreme right who died in 2022.

‘A Farsa Ianomâmi’ was written by Colonel Menna Barreto and published with public funds by the Army Library. Photo: Brazilian Army PMPV

Another person who turned against the Yanomami was Colonel Gelio Fregapani, in an article for far-right websites that discuss military matters. In 2014, in an interview with Revista Verde-Oliva, the Army’s official magazine, he spoke about the “dangerous Indigenous situation” and was didactic: “The Army has to think and implement actions to achieve allies among the Indians [sic] and, especially, miners. The latter, in the current situation, would be the key to success or failure.”

Fregapani, who is currently 88 years old, granted an interview to SUMAÚMA. Courteous and obliging, the answers he gave over a 15 minute phone call are a sort of compilation of how most of the military thinks about the Amazon. “I love the forest, but the forest has no real interest [for anyone]. The real interest is the ore that is found in it,” he said.

The colonel’s words contradict the evidence gathered by scientists, researchers, and public agencies on the region’s problems.

“The miners leave no trace that they were there. The ill they cause to the environment is an illusion, a fallacy. They deforest an area no larger than a city block. Actually, the Indians [Indigenous people] like them, because they give them food. What is the Indians’ problem? It’s hunger. The forest can sustain a small group. But as the group grows larger, it doesn’t sustain them.”

Illegal mining opens gaping wounds in the forest, like this one in the Munduruku Indigenous Territory, contrary to what the military maintains. Photo: Marizilda Cruppe/Amazônia Real

If this were true, the Portuguese would not have found anyone when they invaded what is now Brazil in the 16th century, at which time an estimated 2.4 million Indigenous people lived there, according to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics. As archeology has proven, the Amazon once had between eight and 10 million inhabitants hundreds of years before it was invaded by the Europeans. The military, which opened roads in the Amazon during the dictatorship, also would not have run into resistance from the Indigenous people who defended the territories where they had lived for hundreds of years and, as proven in some areas of the Amazon, for 8,000 years.

One thing in particular that Fregapani says shows the usefulness with which the military regards the presence of illegal miners and land-grabbers in the forest. “If Brazil stopped hounding the miners, it would end unemployment. Because 2 million [people] would go there [to the Amazon]. If there were war, we would totally dominate the forest, without any problem. Imagine what 2 million in the rearguard would look like to a possible invader. No [enemy] army could handle it.”

This statement helps to understand why the ongoing genocide in the Yanomami Indigenous Territory has yet to stop. Reported by SUMAÚMA in January 2023, its main cause is the territory’s invasion by illegal miners. For decades the Army has had two border platoons in the Indigenous Territory and a total of 25,000 soldiers across the Amazon, yet it was not capable of handling a far smaller number of illegal miners and organized criminals. The Armed Forces hesitated to close the airspace over the region, a fundamental measure to choke the infrastructure used by illegal miners, fed by small aircraft operating on clandestine airstrips in the forest. They closed a support post that was used to refuel helicopters used by Brazil’s environmental regulator, Ibama, in operations in the region. When demands were made to deliver basic food items to the Yanomami, they provided this service to such an irregular and costly extent that the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples preferred to hire a private air taxi instead.

A 2023 aid operation to Yanomami Territory relied on little help from the Army. Photo: Michael Dantas/AFP

For researcher Adriana Marques, with the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, the military’s beliefs about the Amazon remain unchanged among younger officers. “This is conveyed more through their process of sociability than through what is taught at Aman [the Agulhas Negras Military Academy, where all Army officers are trained]. There is a period, when new officers are formed, when they go to the Amazon for training on forest warfare. And there they here these narratives about international greed for the Amazon, their role in protecting the region,” she explains.

Even if it doesn’t play a central role in the career of every member of the military, the ideology on the forest is what Adriana calls the “central element of opposition” to progressive policies, non-governmental organizations, a progressive Catholic church, and foreign leaders. “Quotes like the one from [French president Emmanuel] Macron or from Cacique Raoni trigger something in the [military] imagination,” she says, recalling how both criticized the Ferrogrão, the railway coveted by large soybean farmers in the state of Mato Grosso to carry their product to one of the Amazon’s river ports.

“This conspiratorial view coexists, let’s say, with a more rational view. The military cooperates, for instance, with lots of non-governmental organizations, not all are seen as conspiratorial. There is openness to conversations with civilian specialists, including anthropologists, sociologists, among the younger generations, the care taken not to have an inappropriate posture in contact with the Indigenous peoples, even because of a legal concern. Yet what has not changed and is orienting all of this is the view that they are there as civilizing agents. This guardianship view is very clearly expressed in the Amazon, even though it shifts with the political winds. In the Bolsonaro administration, the conspiratorial view [of international greed] returned. Today, in the Lula administration, the focus of action in the Amazon is on humanitarian aid,” says the researcher.

SUMAÚMA sent the Army a series of questions about the Amazon, military doctrine on the forest, critiques made by researchers, and historical errors made in the region by the dictatorship. Instead of responding, a statement was sent: “The Army acts in its constitutional mission to defend the homeland and, through subsidiary actions, cooperating for decades with the government and with agencies in protecting the Amazon, including its assets, in areas of Original peoples, in fighting fires and cross-border crimes, and others. It has contributed to national development, following the criteria established by law and in current norms related to the environment.”

‘Eternal commander’

March 17, 2023 was a day to celebrate at the Forest Warfare Instruction Center in Manaus. The facility that prepares the Army’s soldiers to fight in the forest welcomed Gelio Fregapani as its illustrious guest. The sixth official to command the unit, the reservist colonel is lauded as a hero by the soldiers serving in the Amazon, as reported by various researchers to SUMAÚMA. He is also the author of the Army’s “Laws of War in the Forest,” a brief list of instructions such as “think and act as a hunter, not as the hunted” and “always fight with intelligence and be the most cunning.”

Fregapani was welcomed with honors by the unit’s current commander, Colonel Glauco Corbari Corrêa. “At the occasion, Colonel Corbari thanked the Eternal Commander [Fregapani] for the lessons conveyed, for the guidance received, and for the entire legacy he left, particularly in matters of doctrinarian experimentation in the Forest Operations Courses and the Forest Warfare Instruction Center itself, with many lasting to this day, with extremely positive impacts for the Army,” reads the text reporting on the visit, which is published on the unit’s website.

SUMAÚMA asked why the Army welcomed with honors a retired official who has been investigated for cooperating with a guerrilla faction and who has a history of statements about Indigenous peoples that are seen as prejudiced and scientifically incorrect. A response was provided. The Federal Police said it shelved the investigation targeting Fregapani in 2012. This was why he was never indicted.

Now 88 years old, Gelio Fregapani has been receiving the same amount of pension payments given to a brigadier general. He occasionally gives interviews and writes articles for far-right media channels, where he is introduced as “a legend.” Exactly how he continues to be seen by his military colleagues in the Amazon.

Even with two platoons near Yanomami Territory, the Army did not detain the miners who brought death to the territory. Photo: Fernando Frazão/Agência Brasil

Report and text: Rafael Moro Martins

Editing: Eliane Brum

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Fact-checker: Douglas Maia and Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Spanish translation: Julieta Sueldo Boedo

English translation:Sarah J. Johnson

Copyediting and finishing: Natália Chagas

Editorial workflow coordination: Viviane Zandonadi

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum