At the Free Land Camp (ATL) in Brasilia, President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva made a promise that he is unlikely to be able to keep: not to leave any Indigenous land without demarcation. To keep his pledge, he will have to go beyond what he did in his first two terms in office (2003-2010)—and under much more adverse conditions than he faced back then. At the nineteenth ATL, Lula ratified the demarcation of six Indigenous territories, less than half of what had been expected by Indigenous leaders. To compensate for the deficit in actual demarcations, he made a promise more in keeping with a politician on the campaign trail rather than a president confronting enormous difficulties posed by a distinctly anti-Indigenous Congress. Lula did not make his pledge to an empty audience: it was heard by the thousands of Indigenous people who were present at the ATL, posted on the social media of leaders and influencers, and will not be easily forgotten.

Lula’s promise reveals the dilemma faced by his government. Brazil is thirty years behind schedule in its plans to demarcate the totality of Indigenous lands, a delay that is responsible for conflicts, massacres, and the murder of Indigenous people. Moreover, it has been proven that the Amazon rainforest and other biomes that are still standing are largely those where Indigenous peoples live in demarcated territories. In times of climate crisis, demarcation is therefore not only a question of justice but also one of survival—and of concern to the entire planet. Protection of the Amazon is what ensures Brazil’s relevance right now, guarantees international investment in the country, and provides prestige for Lula.

Joenia Wapichana, FUNAI president, gives Maria Leusa Munduruku an emotional hug after signing the official letter recommending issuance of a declaratory decree for the Sawré Muybu Indigenous Territory. Joenia announced that the process of recognizing Munduruku land would move forward, and she received members of the Munduruku people at FUNAI during the Free Land Camp, in April 2023. Photo: Fernando Martinho/SUMAÚMA

The problem is that Lula is governing a country dominated by a predatory, negationist, and backward economic elite, represented by the Ruralist Bloc in Congress. On the one hand, Lula is under pressure from Indigenous people and international governments worried about the intensification of global heating. On the other hand, he is up against a hostile Congress dominated by a highly organized, well-financed ruralist group. This may well be the biggest challenge Lula has encountered in his entire political life—and never before has the future of new generations depended so heavily on the moves he will make.

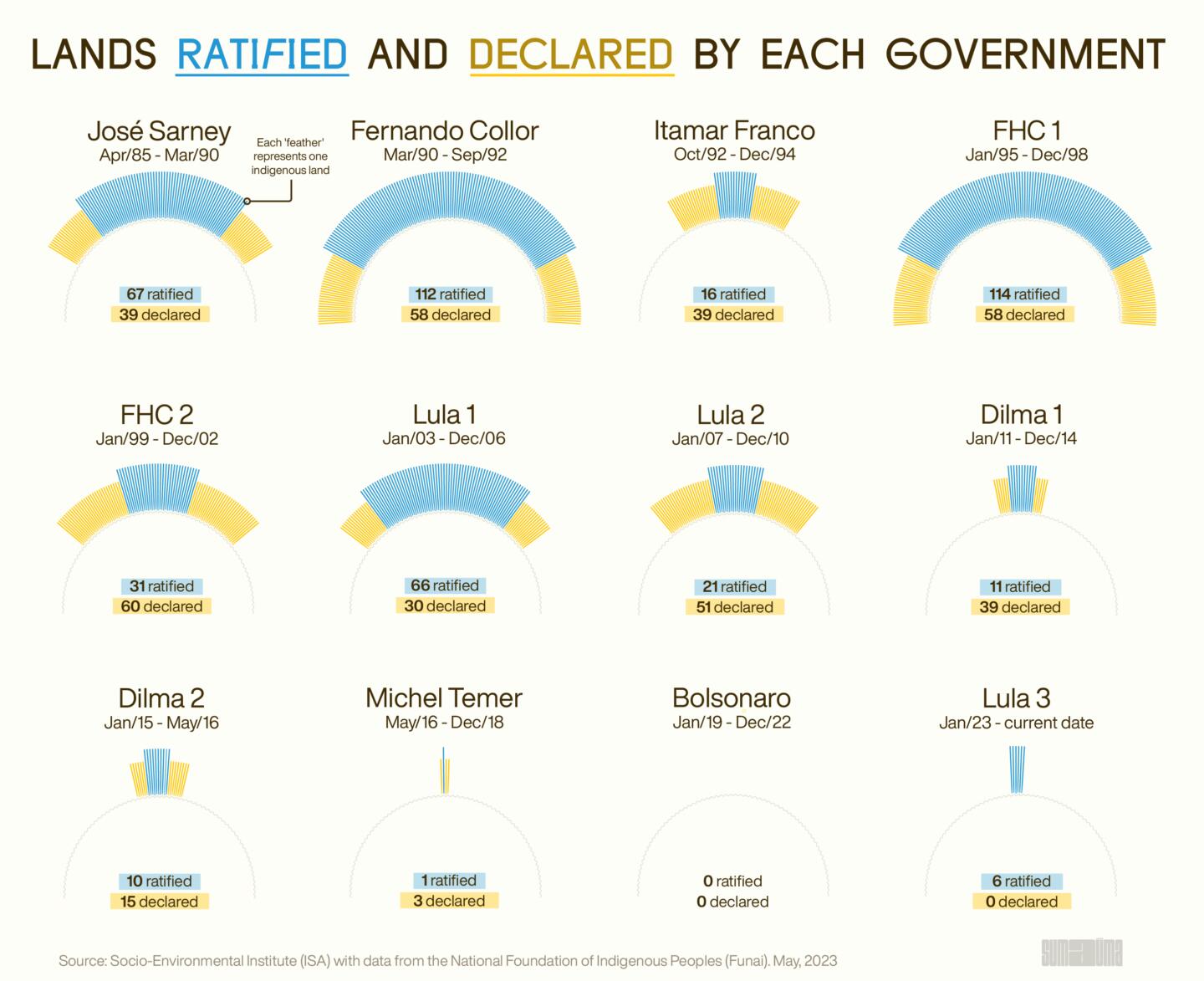

During his first eight years as president (2003-2010), under much more favorable conditions, Lula finalized the establishment of a mere eighty-seven Indigenous territories. There are currently 251 demarcation processes tied up in federal red tape, according to official figures from Brazil’s agency of Indigenous affairs, FUNAI. The Socioenvironmental Institute (ISA) has tallied 237 processes as under study, defined, or already declared as Indigenous lands to be demarcated. The ISA survey uses FUNAI’s own data, but there are slight differences in their calculations of the number of lands whose processes are in the initial phase, which is when a study group is set up to define the territory. According to the ISA, there are 124 processes with the latter status, while FUNAI puts the number at 140. The difference lies in the sixteen working groups announced since the start of the year by FUNAI president Joenia Wapichana. The ISA assessment is that many of these processes had already been underway, but they were then suspended or their deadlines expired, and so the institution did not count them as new.

“Since the ISA began to do the work of tallying Indigenous lands, in the 1980s, we have amassed roughly 7,000 documents. It is an enormous challenge to organize these records, because the process of demarcating Indigenous land is not linear; there are back-and-forths, judicial decisions that suspend them, and government decrees that restart them,” explained the anthropologist Tiago Moreira, from the ISA.

According to the ISA survey, available on the site Terras Indígenas no Brasil [Indigenous lands in Brazil], 496 Indigenous territories have already been ratified and regularized, along with another 237 processes that are ongoing. The whole procedure usually takes years, sometimes decades. Demarcation of the Avá-Canoeiro Indigenous Territory, in the state of Goiás—one of the six ratified by Lula at the ATL—had been dragging on since the 1990s. The signature of the president of the Republic is the final bureaucratic step in the demarcation of Indigenous lands.

“[Demarcation] processes do not move forward by themselves, they need people who do the work,” FUNAI president Joenia Wapichana told SUMAÚMA in an interview. Joenia estimates that the agency is 1,200 employees short. A document from FUNAI itself, dated June 2022, reveals that the real picture is even worse: only 1,420 of the 3,732 positions are filled, or 38% of the total.

Among the more than two hundred lands where processes are now underway, sixty-eight have been declared locations of traditional Indigenous occupation but their boundaries have still not been physically demarcated. This is the last step before they can be ratified by the country’s president. Another forty-five Indigenous territories have been identified but are awaiting the signature of declaratory decrees by the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples, so that physical demarcation can be carried out. The declaratory decree is the phase in the demarcation process in which the government recognizes the area as being earmarked for one or more Indigenous groups. In this document, which is one of the final stages in the process, the minister declares the geographical boundaries of the Indigenous territory and orders the physical demarcation of the area.

Most of the 237 demarcation processes—124, according to ISA figures—are only at the initial stage, in which working groups undertake studies to identify and define the Indigenous area. Joenia states that the conclusion of the initial phase of the demarcation process “is a job that under normal conditions takes about 180 days.” The president of FUNAI has already authorized the establishment of fourteen of these working groups. Coordinated by anthropologists who are career employees at the agency, the groups draw up a report presenting the conclusions of ethnic, historical, sociological, legal, cartographic, and environmental studies, in addition to the land survey that will establish the size and boundaries of the Indigenous territory.

“There are requests [to create study groups] that were made ten, twenty years ago. There are more than hundreds of processes that still have to be put in motion,” said Joenia. To a large extent, this backlog is due to staff shortages at FUNAI. In an attempt to remedy at least part of the problem, in early May the Minister of Management and Innovation in Public Services, Esther Dweck, authorized a civil service examination to fill 502 vacancies in the federal agency. The majority of these vacancies—304—were for the positions of Indigenist Expert and Indigenist Agent. This will be the federal government’s first selection process for FUNAI since April 2016.

“Seven years had gone by without FUNAI receiving any attention, or any investments,” Joenia says. “My first action was to gather the employees and assess the situation. I realized they are very discouraged, after a number of years of persecution and even murders, as was the case with Bruno [Pereira, an Indigenous expert who was murdered in June 2022 in Javari Valley along with British journalist Dom Phillips], a lot of the staff working at the agency are suffering from depression.”

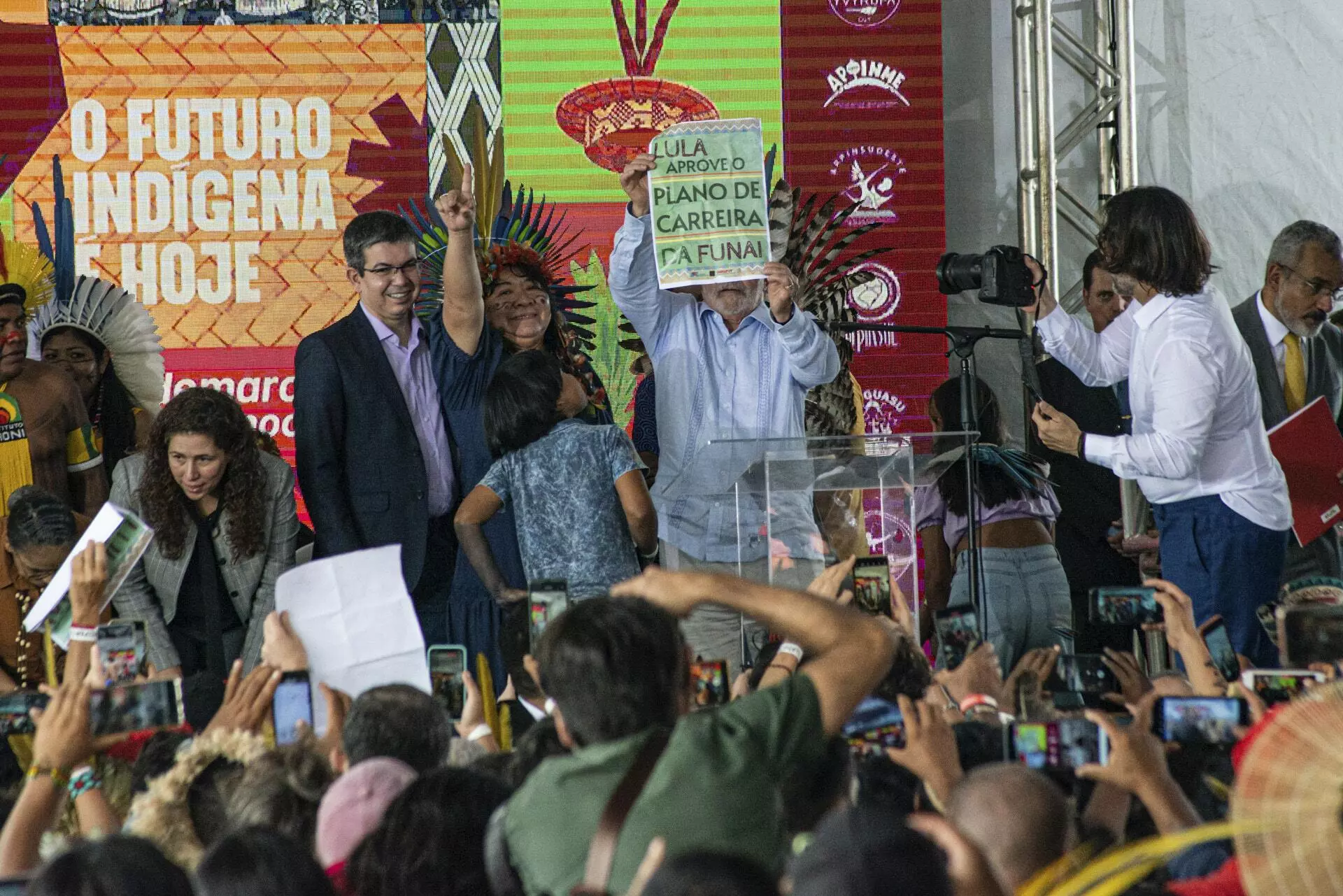

However, the salaries for the new positions are not very attractive: 6,420.87 Brazilian reals a month for Indigenist Expert and 5,349.07 Brazilian reals a month for Indigenist Agent. “They are totally out-of-date,” admitted Joenia. Because of this, FUNAI staff are demanding the creation of a plan for positions and salaries, which Lula also committed to at the ATL. “We don’t want FUNAI staff to be treated as if they were second-class employees. For this reason, we will take great care in seeing to your career plan,” he promised. However, no deadline has been set for a solution.

In 2015, a report by the Federal Audit Court warned that “the quantitative and qualitative shortage of personnel is a chronic problem at FUNAI” and the “aging of the staff without timely replacement results not only in a loss of operational capacity but also [in] a loss of technical knowledge that is exacerbated by the aforementioned absence of any internal policy for staff training and continuing education.”

President Lula, who was at the Free Land Camp on the last day of the event, holds up a poster from Indigenous leaders calling on him to approve a career plan for FUNAI staff. A staff shortage and low salaries are obstacles to strengthening the workforce at FUNAI, which was dismantled by the Bolsonaro government. Photo: Matheus Alves/SUMAÚMA

In 2003, Lula succeeded Fernando Henrique Cardoso (Brazilian Social Democratic Party, or PSDB), who signed the demarcation of 145 Indigenous territories during his two terms and established effective conditions for FUNAI to carry out its work. In 2023, when the Workers’ Party president entered office, he found that the agencies responsible for Indigenous policy had been completely dismantled by the far-right politician Jair Bolsonaro.

The National Constituent Assembly (1987-1988) set a five-year deadline for the complete demarcation of all Indigenous lands in Brazil, counted from enactment of the country’s new Magna Carta. In October of this year, it will be thirty years since this deadline expired. This means the State is three decades behind in its compliance with a constitutional ruling.

It cannot be said that the 237 lands listed by the ISA are the last ones claimed by Indigenous peoples in Brazil. The report “Violence Against Indigenous Peoples in Brazil,” published in 2022 by the Indigenist Missionary Council (CIMI), tallied 1,393 Indigenous lands in the country in 2021. No official steps had been taken toward recognizing 598 of them. In other words, they had not even entered the initial phase of the demarcation process. FUNAI works with similar data to the ISA. Neither of these two institutions takes into account lands claimed but not yet included in the official demarcation processes, contrary to CIMI.

Demarcated and protected Indigenous lands play a fundamental role in the attempt to halt the advance of the climate catastrophe. In 2020, the scientific journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences published research that confirms the essential role of Indigenous peoples and traditional populations in climate stabilization. Indigenous peoples are the most effective in terms of maintaining carbon stocks; in their demarcated lands, they help regulate the climate and prevent even greater heating of the planet. This was something that President Lula acknowledged on April 28 at the ATL: “We are going to have to work hard so that we can demarcate as many Indigenous lands as possible. Not just because it is a right, but because, if we want to reach 2030 with zero deforestation in the Amazon, we will need you.”

The delay in demarcation aggravates conflicts such as the one recorded at the Morro dos Cavalos Indigenous Territory, in Palhoça, on the coast of the state of Santa Catarina. There, six hundred Guarani Mbya and Guarani Ñandeva Indigenous people have been the victims of attacks from speculators who are interested in their land, which is located between federal highway BR-101 and the seashore. The demarcation process has been at a standstill since 2008. In the southern part of the state of Bahia, where Pataxó Indians have been waiting for the demarcation of the Aldeia Velha Indigenous Territory since 1998, a teenager was murdered by gunmen in September 2022. The Indigenous movement had hoped that Lula would sign the ratification of the Morro dos Cavalos and Aldeia Velha Indigenous Territories in April—but he was thwarted.

With their Indigenous dances, a group of Guarani signals their arrival at the opening of the nineteenth Free Land Camp, whose theme this year was “The Indigenous future begins today. Without demarcation, there is no democracy!” Photos: Fernando Martinho/SUMAÚMA

The lengthy demarcation process

Once ready, the report containing the studies and conclusions of the working group that examines the demarcation of an Indigenous territory is submitted to the president of FUNAI, who is responsible for approving it. Since early 2023, only two of these processes have been stamped by Joenia, recognizing the Sawre Ba’pim Indigenous Territory, of the Munduruku people, in Itaituba, state of Pará, and the Krenak de Sete Salões Indigenous Territory, of the Krenak people, in Resplendor, state of Minas Gerais.

Once the report has been approved, a summary has to be published in the federal Official Gazette and in the Official Gazette of the state where the future Indigenous territory is located. Once this is done, a ninety-day period for filing objections begins. Individuals, companies, municipalities, and governments can question the report and ask for compensation. Once these objections have been received, FUNAI has sixty days to prepare answers to each one of them and then, up until 2022, forward everything to the Ministry of Justice and now, since 2023, to the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples.

This is the point at which the thirty-day period begins for the ministry to decide whether the process is eligible to go forward. In this case, a directive must be issued declaring territory boundaries and defining its physical demarcation. On the other hand, if the ministry deems that there are problems in the process, it can return it to FUNAI and ask the agency to take additional steps. This possibility provides a loophole for governments that want to block demarcation: in 2019, the then-Minister of Justice, Sergio Moro, returned a number of processes that were on his desk to FUNAI for “adjustments” in order to ensure that Bolsonaro would fulfill his pledge to “not demarcate one more centimeter of Indigenous land.”

There are at least forty-five demarcation processes waiting to be signed by Indigenous Peoples Minister Sonia Guajajara. The report of the transition government’s technical group recommended that declaratory decrees be issued in the case of twelve of them. This is the batch of processes that then-Minister of Justice Sergio Moro ordered to be returned to FUNAI in 2019. At the time, they were ready for the declaratory decrees to be issued. With the measure, Moro prevented these processes from moving forward. Although further processing depends only on the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples, it has not yet occurred, due to inadequate structure and the shortage of personnel.

Suffering a shortage of resources and targeted by the ruralist caucus

Created in January, the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples has a blatantly precarious structure. The ministry doesn’t even have its own staff, and in the little more than four months of its existence, it has already become the favorite target of the so-called ruralist caucus, which wants to wipe it off the map. A lawsuit filed by the Progressive Party has asked the Federal Supreme Court to withdraw ministry authority to demarcate new Indigenous territories. Federal deputy Sergio Souza (Brazilian Democratic Movement party, or MDB, state of Paraná), who presided over the Agricultural Parliamentary Front from 2021 to 2022, wants to go even further. The politician presented an amendment to Provisional Measure Number 1,154, proposing that the ministry be abolished. The measure, signed by Lula on his first day in office, established the federal government’s current structure, which includes the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples, but it must be approved by Congress.

Once the declaratory decree for an Indigenous territory has been published, the process returns to FUNAI, so that the area can be physically demarcated. This is the most expensive part of the process because it requires the contracting of specialized companies that will go into the field to locate territory boundaries. According to the ISA, sixty-eight of the demarcation processes are at this stage.

“Due to the limited number of current technical staff , georeferencing work is done by contracting through a bidding process open to topography and geodesy companies,” explained FUNAI, in a written response to SUMAÚMA’s questions. “There are about fifty Indigenous territories that still have to be georeferenced, and a bidding process has been initiated for contracting in some areas, which have not yet been stipulated due to budget.” In plain language: there are no funds available.

This is also the phase during which any non-Indigenous people who, for whatsoever reason, are occupying the Indigenous territory, are removed. According to legislation, there is no need to indemnify squatters, farmers, or ranchers who live or produce on territory that has been declared as traditionally occupied by Indians. On the other hand, compensation is payable for any improvements made by them in the area, provided they have been made in good faith. There are complicated cases in which non-Indigenous occupants were brought to Indigenous lands under government programs in the past, which is a radically different situation to the usual one of invasions by land-grabbers.

“To get an idea, the amount of compensation payments for improvements made in good faith on the fourteen Indigenous territories identified as eligible for approval [following Lula’s election], totals something over one billion Brazilian reals,” Kleber Karipuna, one of the executive coordinators of the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB), as well as the coordinator of the technical group of Indigenous peoples in the transition government, told SUMAÚMA. The high cost of compensation represents yet another obstacle to the promise made by Lula at the ATL.

Kleber Karipuna, like some Indigenous leaders, heard the president’s promise but chose to focus on reality: “We are very aware that the little more than three years and eight months since the Lula administration [has left in office] will not be enough to remedy the demarcation deficit.” This cautious approach may not sit well with the thousands of Indigenous people who suffer daily violence from invaders because their lands have not been demarcated—and who have great respect for the word of a president.

Spell check (Portuguese): Elvira Gago

Translation into Spanish: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Mark Murray. Edition: Diane Whitty

Photography editing: Marcelo Aguilar, Mariana Greif and Pablo Albarenga

Page setup: Érica Saboya

The grave of Clodiodi Aquileu, a Guarani-Kaiowá health agent who was murdered at the age of 26 during the attack known as the Caarapó Massacre. For decades, the Guarani-Kaiowá people have been awaiting the demarcation of their territories in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul. Conflicts with farmers and ranchers along with the murder of Indigenous people have been a constant reality since the early 2000s. Photo: Pablo Albarenga/2017