On 18 August, Maial Paiakan Kaiapó – a young indigenous woman running for a seat in Congress in the upcoming Brazilian elections – is on her way to the town of Ourilândia do Norte in the south of the Brazilian state of Pará, where many of the just over 33,000 residents earn a living from various forms of agriculture – not all of them legal. A stop in Xinguara, 147 kilometres from Ourilândia, reveals the hostility towards indigenous candidates in Brazil, where voracious growth in agribusiness is a priority of the country’s far-right President Jair Bolsonaro.

When Maial’s sister Tania, who is accompanying the congressional hopeful on the trip to some of the Kayapo villages in the state, goes into a simple pharmacy for a drink of water, a tall white man in boots and belt glares

aggressively at her. Shortly afterwards, a blonde woman – also white – enters the shop and does the same. Is a typical reaction in the region, explains Tania, who like many of Brazil’s indigenous peoples is of average height, with dark eyes and hair. “People are very hostile in Xinguara. In fact, this is how the Kayapo are treated in many parts of southern Pará,” she says. Over half the population of Xinguara voted for Bolsonaro in the last elections.

Maial’s campaign as a candidate for the Sustainability Party officially began on 16 September, in Belém, the Pará state capital. I met her for the first time the next day, 905 kilometres away in the city of Redenção. For the next few weeks, I followed her on the campaign trail, observing what life was like for an indigenous candidate in the Amazon, the most under threat territory in the environmental battle raging in Brazil. For Maial, the situation is critical. “We’ve reached the stage where we need to put the right people in power, and fast. And by the right people, I mean those who understand the reality of life in our villages, who respect every life in the forest,” explains the 34-year-old Kayapo.

Another sister, Cacica O-É Paiakan, was the original choice to be the Kayapo candidate in these elections. When she became pregnant, however, the community unanimously agreed that Maial should take on the challenge.

Born in Belém, Maial was brought up in the village of Aukre, immersed in the indigenous way of life. She experienced life in a non-indigenous environment while attending college in Redenção, 280 kilometres from the state capital, and a city that owes much of its growth to land grabs and the invasion of indigenous territories. There, the local economy is heavily geared towards cattle farming, evidenced by the slaughterhouses on the margins of the PA-287 highway which slices through the region. In addition to cattle, soya farming is also practiced in the area.

For an indigenous candidate, campaigning in cities where the local economy is dominated by land grabbers, loggers and ranchers presents greater dangers than just hostile stares in a pharmacy. But given the threat to her people, Maial had no choice but to take on the challenge. More land is deforested in Pará than in any of the other eight states that make up the Amazon region, according to data from the Deforestation Warning System of the Amazon Institute of People and the Amazon. A total of 3,858 square kilometres of forest were cut down in the state between August 2021 and July 2022, 36% of the total area deforested in the Amazon.

Although the campaign represents Maial’s debut as a candidate, her introduction to politics came early: her father was Paulinho Paiakan, a Kayapo leader who fought for the inclusion of indigenous rights when Brazil’s new constitution was drawn up in 1988. “He always encouraged us to go to the city to study,” she recalls. “He told us that in the future we wouldn’t just help the Kayapo, but all indigenous peoples.” In 2020, Paulinho died from Covid-19 – abandoned, like many indigenous people, by the Bolsonaro government, which was slow to roll out the vaccine, and even distributed chloroquine in villages.

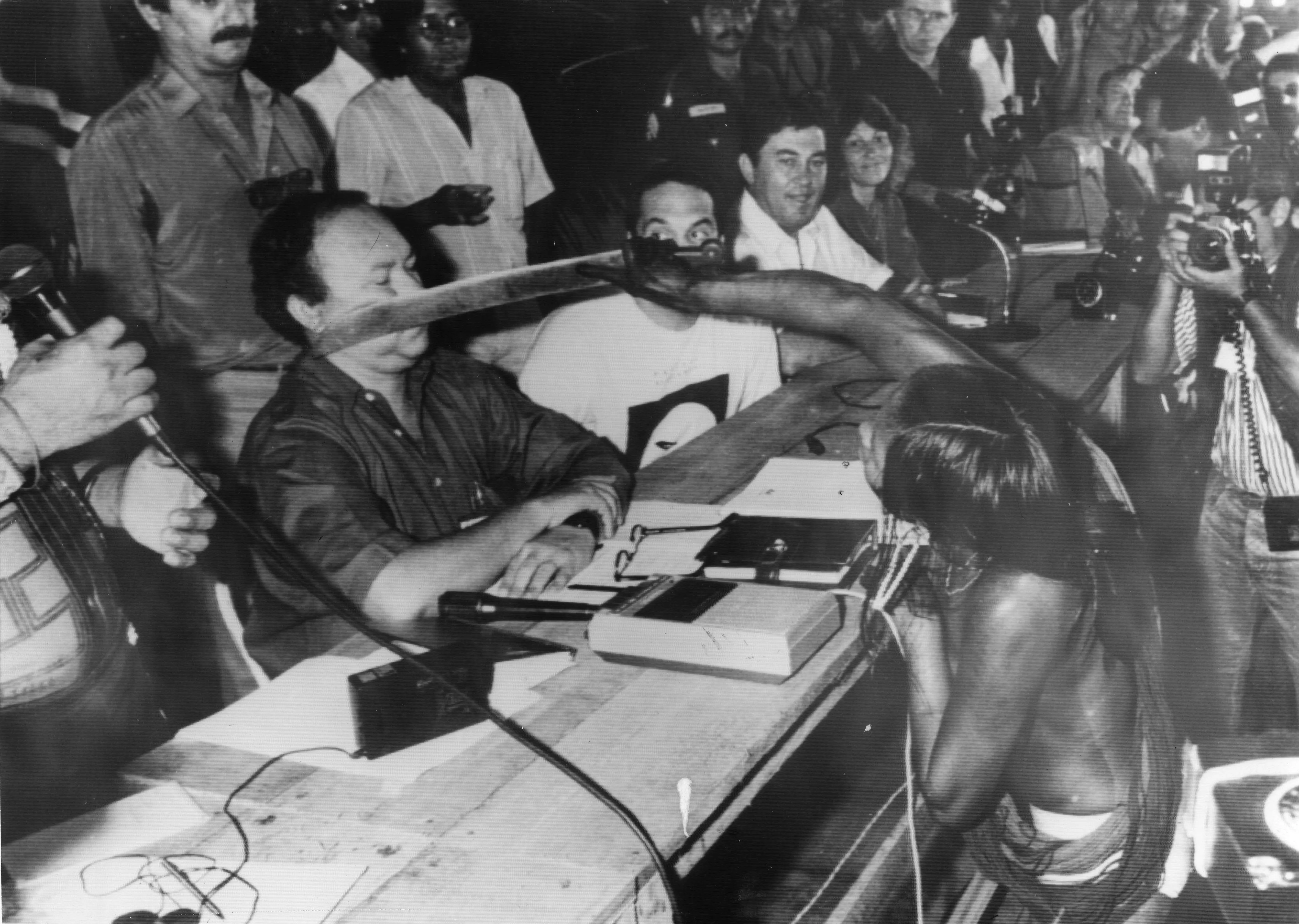

Maial is also great-niece of Kayapo chief Raoni Metuktire, a global figurehead of the indigenous struggle, and niece of Tuire, a symbol of female resistance to the threat faced by Brazil’s native peoples: a photo showing her putting a machete to the face of a director from the Eletronorte electricity company in Altamira in 1989 was seen around the world, and helped to slow the construction of the disastrous Kararaô dam, on the Xingu River – later renamed Belo Monte.

Tuire Kayapó draws a machete across the face of Eletronorte’s director, José Antonio Muniz Lopes, in a demonstration against the construction of Kararaô dam, renamed later as Belo Monte. Image: Protásio Nene (21/02/89)

Militancy runs in Maial’s blood. Alongside her sisters, Tania and Cacica O-É Paiakan, she grew up listening to her father talk of the importance of the fight for indigenous rights. They were encouraged to learn everything they could about the subject and to keep a watchful eye on the passing of laws in the Brazilian capital of Brasilia that might represent a threat to their people.

To prepare herself for the struggle ahead, Maial obtained a law degree, the first of the Kayapo to do so. In 2016, she worked as an advisor to the president of FUNAI, Brazil’s indigenous protection association, where she helped to analyse and monitor legal actions relating to the demarcation and protection of indigenous lands. From 2017 to 2019 she was a legal advisor at the Special Department for Indigenous Health (SESAI). After that, worked under Joênia Wapichana, who in 2018 was the first indigenous woman to win a seat in the Brazilian Congress. Wapichana opened the way for other indigenous women, such as Maial, to enter politics and to support each other in the fight for the rights of their people.

Of the 186 self-declared indigenous candidates in the 2022 elections, 84 are women, according to data from Brazil’s Supreme Electoral Court (TSE). In 2018, the number was 130, tiny in comparison with Brazil’s 28,931 non-indigenous candidates. In the short and turbulent history of Brazilian democracy, however, it represents an important step.

Of the candidates, 34% are female, in a country where women were only guaranteed the right to vote in 1932. But there is still much work to be done to ensure the equal representation of women in Brazilian politics – the first female toilet in the country’s Senate was only installed in 2016. Prior to this, female senators had to use the bathroom in a restaurant attached to the building.

The young Kayapo comes from a culture of strong women, who have an active voice in the political decisions that affect their community – emphasising the injustice of indigenous peoples having their destinies decided by white politicians, and being left with no way to express their views. It is literally a matter of life and death – according to figures from the Indigenist Missionary Council (CIMI), 176 indigenous Brazilians were murdered in 2021, and 182 in 2022. “The bullets that hit us are rubber stamped by the Planalto Palace (the seat of the Bolsonaro government) and Congress,” says Sonia Guajajara, an indigenous congressional candidate for the Socialism and Liberty Party (PSOL) in São Paulo. The numbers of indigenous murders have grown alongside the increase in illegal mining and logging activities, treated with indifference by the Bolsonaro government.

But without indigenous peoples there can be no life on the planet, warns Maial. “We are many (different tribes), but we face the same problems: mining, land grabbing, illegal logging, the need to demarcate our lands,” she says. “I believe that now more than ever we understand that things will only change when we also change those who make the laws in Brasília. It will only change when we ‘bring the village’ to politics,” she adds, by which she means taking the idea of the collective into Congress.

The Kayapó candidate distributes campaign material in Santarém. Image: Kevin Gonzalez

And at the same time, opposing the plans of Brazil’s farming caucus, a group of more than 200 members of congress that seeks immediate profit for a minority of land grabbers and ranchers, bringing destruction to the forest and indigenous lives. Pará, the second largest Brazilian state after Amazonas, is made up of 144 municipal regions, which often differ wildly from one another – the state capital Belém, for example, is a sprawling metropolis of more than 1.5 million inhabitants. But in the south of the state, several of the areas visited by Maial have one thing in common: they are towns that live off the activities of land grabbers and farmers, with people either working in agriculture itself or in related activities, such as in agricultural supplies or animal feed stores, or slaughterhouses.

Maial’s sister Tania serves as her campaign coordinator, while in Redenção, her nephew Kauã Paiakan helps distribute publicity material before the team sets out for Ourilândia – stickers bearing her face, name and candidate number: Maial Kayapó, congressional candidate, 1818. “We face many challenges and we’re tackling them in a thousand different ways. I expected an electoral campaign to be tough, but for an indigenous woman the challenge is even greater,” says Tania.

Life in general has been a challenge for Brazil’s indigenous peoples under the Bolsonaro government, which has slashed the funding they receive. The shabby state of the former FUNAI headquarters in Redencão is a visible sign. A vital support centre for the indigenous peoples of the region, and a transit hub for parents bringing their kids to study – with only primary schools available in the villages, those who want their children to go to secondary school must travel to urban areas. Yet while the centre of the town has a number of paved roads (not always common in the Amazon, where the climate makes tarmacking a challenge) and basic sewerage, the former FUNAI headquarters is surrounded by dirt roads, and cars, trucks and motorcycles kick up clouds of red dust, turning the streets and houses the colour of clay.

By three o’clock in the afternoon, when the meeting with the Kayapo is due to start, the thermometer reads 36 degrees Celsius, with a feels-like temperature of 40. Maial walks slowly and weakly into the room. “I’m pale, aren’t I?” she says, when I ask if she’s ok. Since the start of the campaign she’s complained of pains, nausea, and a general sense of being unwell, but hasn’t yet seen a doctor about her condition. She carries a bottle of water and another containing an amber-coloured concoction, a herbal remedy prepared by a family member.

The chairs at the meeting are arranged in a circle, as unlike non-indigenous politicians who campaign with microphones and sound trucks, Maial listens to everyone who comes to the centre of the circle to speak. In the weeks to come, it is this that stands out the most – that she listens more than she talks, and only speaks when others are silent.

Maial listens to Tuire Kayapó speaking inOurilândia do Norte. Image: Catarina Barbosa

The 258-kilometre journey from Redencão to Ourilândia takes four and a half hours by car, along highways with crater-sized potholes and stretches of dirt road. At times we have to pull over to the side of the road, where there’s no hard shoulder, as the dust stirred up by passing vehicles covers the rental truck and makes it impossible to see. The roads in the region are inextricably linked to the extermination of indigenous peoples, and are constantly being swallowed up by the forest. For safety reasons we drive slowly, stopping off in Pau D’arco, Agua Azul do Norte and Xinguara, where the intimidating scene in the pharmacy takes place.

Despite saying she’s fine, Maial’s state of health continues to deteriorate during the trip. Later, Tania will tell us she was sick during the night, suffering from fever, headaches, and pain all over her body. In a few days she’ll discover she has malaria, but for now, unaware, she keeps to her schedule, not wanting to disappoint her supporters. She has precious little time to make people aware of her campaign, and fewer resources.

There are only three people in the campaign team: Maial, her sister Tania and Teresa Harari, who has a master’s degree in Public Administration and Government from the Getúlio Vargas Foundation, and who also acts as campaign coordinator. To economise, Tania and Teresa take turns going on trips. “In each region she visits, we build a [local] network of people who will support her candidacy”, explains Harari. Around two thirds of Maial’s campaign funding comes from the Sustainability Party, with the rest from donations. A large part of this pays for trips across the state.

At last, we make it to Ourilândia, where Maial will also meet her family. Our first stop is at Chácara dos Padres, where a large crowd of indigenous people awaits. They are members of the Protected Forest Association, an organization that represents approximately 3,000 indigenous people from thirty-one villages located in the Kayapo, Mekragnoti and Las Casas Indigenous Territories. When Maial arrives, she is greeted by her mother, Irekran Kayapó. They hug, and Aunt Tuire, also present, breaks down in tears – often a sign of joy in indigenous culture.

Tuire, like Maial’s father Chief Paulinho Paiakan, is an iconic figure in the indigenous struggle, earning the respect of her people through her role in a number of battles, including the opposition to the construction of the Belo Monte dam. Her niece continues to hug and shake hands with relatives one by one. “When you arrive somewhere, it’s respectful to greet everyone,” says Maial. “If there are one hundred people here, I’ll greet one hundred. It is our way of life, part of our traditions, our culture.” They all have their faces and bodies painted, and some even have “1818”, Maial’s candidate number, painted between their eyebrows. Body painting, carried out by women using genipap or annatto, is part of Kayapo daily life.

Genipap paint in particular is thought to provide a kind of spiritual protection. “We paint the body when we are well and healthy, to protect our body and our spirit. Painting with annatto protects us from external threats,” explains Tania. In this first stage of the campaign, Maial went days without paint. “Painting the body now could prevent it from healing. And Maial needs to heal,” explains her sister.

The stop at Chácara dos Padres is brief, as Maial is expected at the Modjãn village, around 30 minutes’ drive away. Night is falling by the time we arrive, and a crowd is waiting at the House of the Warriors in the centre of the village, an important building in the political life and rituals of the Kayapo. Although most of those present are men, Maial’s arrival doesn’t cause a stir. Her father made sure she and her sisters were regular visitors to the centre since they were little.

Upon Maial’s arrival, the women burst into tears, and this time the candidate joins them. She greets everyone before taking a seat, the chairs again arranged in a circle. The first to speak is the chief, Beptori Kayapó. “We’ll be by your side from the beginning to the end. It’s wonderful to have you here. Everything will work out just fine,” he says in Kayapo.

Other leaders recall Paulinho Paiakan’s struggle and achievements for indigenous peoples. “Continue your father’s fight, Maial. He was an example to the Kayapo people, and now it’s in your hands”, says Panhkadjara Kayapó. “After years of waiting, this is the first time I feel I’m being represented,” says Beptori Kayapó. “I never voted for whites, and today you’re here. You are the hope for the indigenous people, speaking the voice of the Kayapo. I’ll never abandon you and we’ll be there to help you, whatever the situation,” he adds.

Those present express the desire of Brazil’s indigenous people to have a direct role in the formulation of government policies that concern them. After listening to her people, Maial cites articles 231 and 232 of the Brazilian Constitution, which recognise the rights of peoples, social organisations, customs, languages, beliefs and traditions, and the original rights of ownership over traditionally occupied lands. “I chose to begin my journey together with you, my people, my family. My father fought hard, but we still have a great deal to do,” she says. When saying farewell, the Kayapo women of the village invent a song for her – “This is our candidate, her name is Maial, and she is here with us.”

When we leave the Modjãn village, we travel the short distance to Tucumã, where we’ll spend the night. Maial is still weak, but the next day visits another village, Turedjãn. Women and relatives speak, giving advice and declaring their support and their hopes for the candidacy of their Kayapo sister. The emotion of the meeting causes Maial to forget her symptoms. But when night falls, her fever and pains return. The plan was to make an early start for the trip to the village of Kokraimoro, in São Félix do Xingu, around two hours’ drive away. Instead, heeding her body’s warnings, Maial decides to rest up before setting off. In the end, however, she is forced to admit defeat, and I receive a message from Tania, telling me the women have decided to return to Redenção to find a doctor.

Before leaving Tucumã, however, the sisters look for a shaman – viewed by the Kayapo as doctors like any other. Tall and white-haired, with genipap-painted cheeks, legs, and arms, Krwyt Kayapó is responsible for taking care of Maial. He carries herbs and roots in a bag, with which he tends to the young woman. “I think a lot about you and your father,” he says. “I’ve never forgotten how he helped build our village”. Despite beginning treatment with the shaman, however, Maial goes back to Redenção the next day, to find a non-indigenous doctor. Once there, they pay for a private consultation so that Maial can get seen quickly. Recognising the seriousness of her condition, the doctor requests a series of tests, including for malaria and leishmaniasis. “She’s anaemic and her spleen is enlarged,” her sister reports. When the results come back, Maial has tested positive for malaria.

Malaria is transmitted through the bite of female Anopheles mosquitoes infected by the protozoan plasmodium, but it is also directly related to the destruction of the rainforest. Maial believes she was contaminated during a pre-campaign visit to the villages of Novo Progresso, a town at the heart of the so-called “Day of Fire”, when on 10 August 2019, land grabbers and loggers set a series of fires that caused up to 2,366 outbreaks in the forest. “A number of my relatives caught the disease,” she says. Her campaign will be put on hold for seven days, the length of time required for the anti-malarial medication to take effect.

A full recovery is essential given the intense schedule that lies ahead: the highlight of which is a meeting with the man intending to defeat Bolsonaro in this year’s presidential election, former Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, in Belém on 12 September.

Fully recovered, she arrives in Belém after a six-hour bus ride from Redenção to Marabá, where she caught a plane to the state capital. At the hotel where several candidates have gathered for a campaign photo with Workers’ Party candidate Lula, Maial appears in red pants, a green blouse, red beaded bracelets and a long red necklace, her face and arms painted with genipap.

After waiting hours for the photo, she makes her way to the rally in Belem’s Parque dos Igarapés. On the journey, she is recognized by students and university professors, who tell her they’re supporting her. At the rally itself, there are indigenous peoples, quilombolas (people who live in communities founded by escaped slaves), residents of riverside settlements, and activists from social movements involved in initiatives to preserve both the biodiversity of the forest and the people who live there.

Lula promises to put an indigenous person in charge of FUNAI. “The cattle herd isn’t going anywhere,” he says – a reference to a term used by former Environment Minister Ricardo Salles who, at a ministerial meeting in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, suggested it was time the “cattle herd” went through the Amazon.

Maial Kaiapó in Belém. Image: Nailana Thiely

Once again in a circle, the Kayapo decide that Tuire, Maial’s aunt, will represent them on the stage with Lula. “My aunt has a story and a history of struggle, and collectively we decided that she should go on stage while I stay with our people”, explains Maial. Witnessing Tuire holding hands with the Worker’s Party candidate symbolizes how the Kayapo and the other peoples of the forest understand the importance of uniting around a single objective: even though Belo Monte, the emblematic hydroelectric plant despised by the Kayapo, was built when the Workers’ Party were in power, it is imperative that fascism is defeated. “As president Bolsonaro said he wouldn’t demarcate indigenous lands, and he didn’t. After he took office, conflicts on our lands increased, health care worsened, and the miners and illegal loggers advanced,” says Maial. But the fight will continue, no matter who wins. “We will demand government policies that respect our communities and our people,” she adds.

I see how awareness of Maial’s campaign has spread beyond the Kayapo a few days later, in Oriximiná in the west of Pará, where after a six-hour plane and speedboat trip she meets chief Juventino Pesiana, of the Kaxuyana people. He is excited by her candidacy. “The current policies don’t work for us, our rights are being violated and our people massacred,” he says. “Joênia Wapichana has achieved a great deal on her own, but with more support, we can do much more”.

With time short, Maial is unable to visit the region’s quilombola villages and communities. Even so, their leader Wirika Wai promises to campaign for her. “We’ll spread your name amongst our relatives. We’ll talk about the importance of voting for an indigenous woman. Rest assured, we’re with you, but don’t forget about us,” he says. Maial promises that she won’t.

Her intense schedule continues, and the following day, she takes part in the 28th March of the Excluded, a counterpoint to Brazil’s official Independence Day celebrations on 7 September. The event is held at the Praça da Matriz, in the city of Santarém, organized by the social ministries working in the region. Around 100 people take part in the act, spreading themselves around the square, and beforehand, Maial speaks to supporters and journalists. On a street alongside the square, a motorcade of flag-waving Bolsonaro supporters, clad in the yellow and green of the Brazilian football shirt, makes a din and provokes the marchers. Maial doesn’t react. Despite the small turnout, the event is arranged in such a way that it fills the entire square. A symbolic example of how when involved in an eternal fight, you have to multiply. The next day, ready for yet another stop on a campaign that won’t end until 30 September, the Kayapo candidate spots a bright blue and black butterfly. “It’s a symbol of good luck,” she smiles. I go back to Belém. And she continues her campaign to bring the village to Brazilian politics. A campaign that won’t end with this election.

Edition: Carla Jimenez

Translation: James Young

The Joênia effect

The words and actions of indigenous congresswoman Joênia Wapichana, of the Sustainability Party of Roraima, echo far beyond the state that elected her. Since taking office in 2018, she has become a source of hope for the nearly 900,000 indigenous people of different ethnicities Brazil, representing them in the Brazilian Congress when their rights are compromised and their lives threatened. Of the 74 petitions she’s raised during her mandate, almost all refer directly or indirectly to the country’s native populations, and her experience has been instrumental in inspiring more indigenous women to run this year. Joênia, who is now running for re-election, has always been on the frontlines.

Noted for combining indigenous touches with a suit jacket during congressional sessions, she has played a key role in the fight for indigenous rights under the Bolsonaro government. At the Covid-19 Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry, for example, as coordinator of the Cross-Party Parliamentary Group for the Defence of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, she presented a dossier arguing that the Bolsonaro government committed the crime of genocide against such peoples during the pandemic.

The document, presented in October 2020, described a series of Government actions that exposed native populations to risks of contagion by the coronavirus, and also examples of deliberate omissions in dealing with the pandemic. The late vaccine rollout, the shutting of health centres, and the failure to recognise indigenous people from non-rural areas as a priority for vaccination were just some of the actions that harmed these populations.

In June this year, after the killing of the indigenous expert Bruno Pereira and the British journalist Dom Phillips in Vale do Javari, Wapichana was one of the most influential voices in demanding public hearings to seek explanations for the crime.

In Congress, Joênia forms alliances with other opposition groups, and uses the fight for women’s rights as common ground with her peers among the parties in power. Her goal is to ensure government policies that consider indigenous peoples and enforce the rights guaranteed by the Constitution. “The role of women and, above all, indigenous women is important, because they’re historically excluded from these spaces of power,” argues Teresa Harari, who has a master’s degree in Public Administration and Government from the Getúlio Vargas Foundation, and whose dissertation, “Policies to Postpone the End of the World”, contains a qualitative analysis of the congresswoman’s time in office. For Harari, there are other legacies to Wapichana’s work. “There are broader effects than the mandate itself, such as encouraging new indigenous candidacies, and raising awareness of indigenous rights among other politicians,” she argues.

The need to strengthen the “headdress caucus” is a consensus among indigenous peoples. Chief Juventino Pesiana Kaxuyana, who lives in Oriximiná, in the west of the state of Pará, recognizes that Joênia Wapichana has done a great deal on her own. “But with more support, we can do much more,” he says at a meeting with Maial Kaiapó, a congressional candidate for the state of Pará. “The current policies don’t work for us, our rights are being violated and our people massacred. We have to fight these challenges and having an indigenous politician in Congress is important,” he adds.

The first indigenous member of Congress was Xavante Mário Juruna, of the Democratic Labour Party, who was elected in 1982. But before Joênia Wapichana, indigenous peoples had waited 30 years to see one of their own in such a role. Wapichana opened the door again in 2018. If it depends on the indigenous women of Brazil, it won’t be closed again.