For a foreigner, it might be hard to understand how Yanomami leaders who are facing a genocide that has killed more than 700 children under the age of five in the last five years due to preventable causes such as worms, pneumonia, and malaria can at the same time bring themselves to ride as celebrities on a float in the Rio de Janeiro Carnival parade. To grasp this, one needs to understand the deeply transgressive roots of Carnival. Transformed into a business, financed largely by the city’s illegal gambling sector, reduced to a spectacle—the parade of a first-division samba school in Rio de Janeiro is all this. But there is something else that always escapes capture—and that something is the insubordination of Brazil’s most popular festival, grounded in resistance to every form of destruction of subjugated bodies. Although this life energy is often nearly devoured by a machine that chews up culture and spits out entertainment, there are times when it is renewed and grows stronger. And everything indicates that the Salgueiro samba school’s Carnival parade this year might be one of those moments, when the two bodies on which Brazil was built—Black and Indigenous peoples—will meet in a movement of catharsis.

It’s no coincidence that Davi Kopenawa—the foremost political leader, shaman, and diplomat of the Yanomami people—demanded only one thing of those responsible for Salgueiro’s parade: that the Yanomami not be portrayed as victims but as agents of resistance. This is what we learn from special reporter Claudia Antunes in her in-depth exploration of the journey and relationships that made it possible for the hillside community of Salgueiro and the forest of the Yanomamis to intersect during this Carnival.

SUMAÚMA analyzes this meeting from the lens of the values defended in our founding manifesto: the urgent imperative to alter our conceptualization of what is center and what is periphery, so we are capable of addressing the climate collapse produced by the dominant minority, composed of billionaires and super-millionaires—who Davi Kopenawa calls “planet eaters” and “commodities people.” This means a city’s geopolitical and cultural center does not correspond to the areas where the wealthiest live but rather to its so-called peripheries, where the majority of the population resists, creating technologies of existence and resistance.

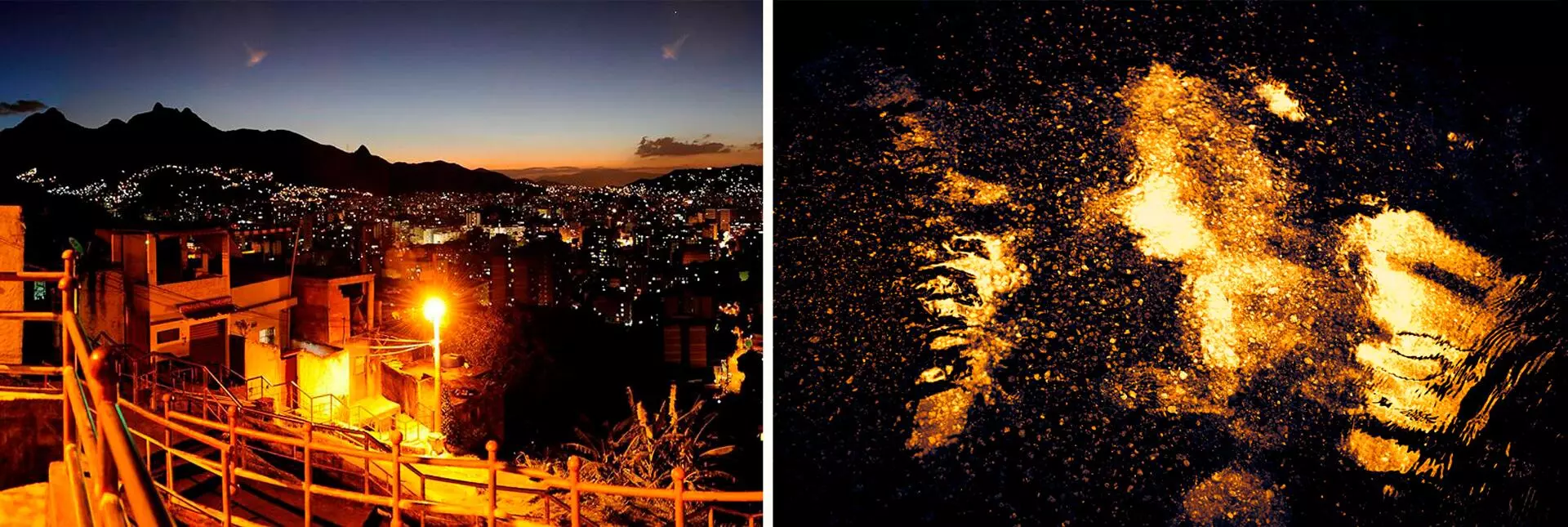

In the favela of Morro do Salgueiro (left), the community resists. In Yanomami Indigenous Territory, the rivers, victims of mining, reflect the sky. Photos: Maurício Hora and Pablo Albarenga/SUMAÚMA

In the case of Rio de Janeiro, for example, the center is not its privileged beachside neighborhoods, with their enduring penchant for slave relations, but the communities and favelas that resist despite all the massacres, currently by militias, drug trafficking, and the State. Similarly, the geopolitical and cultural centers of a planet in climate collapse are enclaves of nature and their peoples—not financial markets and the seats of power that are triggering the overheating of the planet.

From this perspective, the meeting of Afro-Brazilian orixás from the poor communities of Rio de Janeiro with the xapiri spirits of the Amazon rainforest can be seen as a center-to-center connection. Obviously, this meeting is not devoid of contradictions, as we show in a report in this issue. For example, at one point, Davi Kopenawa meets the Salgueiro team for the first time, and comes face-to-face with a man covered in gold jewelry—the gold that is killing the Yanomami through the hands of the miners now destroying the land-forest.

For readers to understand what will happen during the Carnival parade, both as life and as spectacle, Ana Maria Machado, anthropologist and translator of the Yanomam language, and the reporter Claudia Antunes compiled a glossary of Yanomami cosmology. SUMAÚMA also translated Salgueiro’s beautiful samba theme song to the two other languages on our platform, Spanish and English. Our goal is to allow readers of our three languages to grasp the meaning of the relationship between people who are confronting the genocide of Black youth in Brazilian cities and people who are dying from the destruction wrought not only by mining operations, dominated by organized crime, but also by poor healthcare management and the disobedience of the Armed Forces.

There are many points of connection between the extermination of urban Black youth and of the Yanomami population. Today, Yanomami women fear losing their children to narco-mining, a daily torture long engraved in the souls of Black women in favelas—many of whom will be at the Carnival parade, raising their voices against the genocide of their Indigenous sisters’ children.

In the Sambadrome arena, the gold rush that is destroying the future of young Yanomamis connects with the extermination of the urban Black population. Photo: Ewerton Pereira

This connection, even amid pain, is for life. The reahu is the Yanomami funeral rite in which the bodies of the dead, turned into ashes and kept in gourds for months or years, are ingested or buried. Planned over a long period of time, this festival is the moment when everyone grieves the departed so they will settle into the world of the dead and can be forgotten by the living. But the reahu is also pure catharsis, the central celebration in Yanomami life. It is at the reahu that visitors are received from other villages and that dancing and singing are shared—joy, play, and abundance must always be present. New couples are formed, alliances strengthened, exchanges consummated. The funeral festival can only be completed by affirming life.

When the reahu is over, everyone is left with a feeling of nostalgia for the festivities, like the nostalgia left in the bodies who go back inside their houses, apartments, and businesses when it all ends on the Wednesday of ashes. In a way, this Carnival between exterminations is like a reahu.

For someone from Europe or the United States, it may be very difficult to comprehend how joy and genocide can coexist, or how a funeral rite and dancing can coexist. But invoking life, the body, and the senses is perhaps the only way to rexist: to resist in order to exist. This is also why the Bolsonaro far right and market Evangelical fundamentalism have grown so upset over Carnival in recent years. When Carnival takes over the streets, which people usually avoid, and when it pulls bodies from in front of screens so they can incorporate pleasure for a few days and nights, the festival still manages to circumvent all appropriations and persistent attempts to wield control. During Salgueiro’s parade, despite the many contradictions, an alliance will be celebrated among peoples who understand joy as a powerful instrument of resistance—joy as the power to act.

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Spanish translation: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Diane Whitty

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Layout and finishing: Érica Saboya

Editors: Malu Delgado (news and content), Viviane Zandonadi (editorial workflow and copy editing), and Talita Bedinelli (editor-in-chief)

Director: Eliane Brum

The Yanomami asked to be portrayed in a dignified way, as a people who resist. Photo: Ewerton Pereira