Only 15 years elapsed between the moment a smiling President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, his hands smeared with oil, posed for a photo celebrating the start of production at Brazil’s first pre-salt field and the video released for Petrobras’s 70th anniversary, on October 3, 2023, when Lula declared that the state-owned oil giant should “participate much more in the energy transition” in Brazil. Fifteen years isn’t much in historical time. But this period not only witnessed Lula’s reversal of fortune and return to power; it also brought the stark realization that the only way to ward off the climate catastrophe now threatening present and future generations is to end the world’s century-long reliance on oil, which has spawned astonishing material wealth, apocalyptic environmental destruction, and multiple wars.

For many ecological thinkers, “energy transition” falls far short of what the world needs. Not that these theorists don’t think it is essential to stop burning oil, gas, and coal—the fossil fuels that have filled the atmosphere with greenhouse gases, raising temperatures and shifting the Earth’s equilibrium. What they are saying is that simply substituting these fuels with other energy sources—some of which exact their own high tolls on nature and the communities who live in symbiosis with it—is not enough to address an emergency that calls into question the model labeled “progress” and its attendant hyperconsumerism, intense exploitation of nature, and extraordinarily unequal distribution of material gains.

In any case, there is no clear path to energy transition in Brazil. Despite many warnings and the overwhelming succession of extreme weather events in 2023, both the Lula administration and oil companies, Petrobras among them, are planning to produce more oil. Not because Brazil will need it but for export.

Lula’s own message delivered on Petrobras’s anniversary came to nothing less than two months later. According to the state-owned company’s first strategic plan approved under his administration, on November 23, over the next five years investments in new energies will be around 7%, lower than expected.

Emergency in Manaus: woman and child cross the bed of the Negro River, which dried up in 2023 due to both El Niño and the climate crisis, caused largely by the burning of fossil fuels. Photo: Michael Dantas/AFP

Winning ticket, blessing, or curse?

One year after the September 2008 photo op where Lula celebrated the discovery of oil reserves beneath layers of salt and rock, some lying as much as 23,000 feet below sea level, the president made a speech that proved prophetic. Announcing regulations that, among other measures, provided for the allocation of pre-salt funds to education and health, the president said this “winning ticket” could turn from “a blessing” to “a curse”; to prevent this from happening, most profits should stay in the country and be used to fight poverty. Additionally, Brazil should not become a crude oil exporter, like other countries that had “given into the temptation of easy money.”

The bulk of the measures announced by Lula that day were scrubbed after the 2016 impeachment of his successor, Dilma Rousseff (Workers’ Party), who was replaced by coup-backing vice president Michel Temer (Brazilian Democratic Movement). Under far-right president Jair Bolsonaro (2019-2022), monies from the Pre-Salt Social Fund went toward paying off the government’s debt. In late 2022, these resources totaled BRL 19.8 billion ($3.8 billion), equivalent to 0.3% of Norway’s sovereign wealth fund, likewise drawn from oil revenue and the model for the Brazilian fund.

The irony is that today the prospects are good for Brazil to clean up its energy grid (i.e., the energy sources used to keep the lights on, cook food, run machinery and industry, and transport people and goods). Nevertheless, official plans call for Brazil to pump out more oil. This isn’t so much about ensuring the country’s “energy security,” as Petrobras argued when it asked environmental authority Ibama to reconsider its denial of a permit to drill in the Foz do Amazonas basin, an extremely sensitive environmental area off the Amazon shore. Instead, this increased output is intended for sale abroad.

The price tag for exporting pollution will be the destruction of nature. Even if the country manages to fulfill its goals for reducing greenhouse gas emissions and become the “green power” Lula has touted in his speeches around the world, this is a flagrant contradiction.

It is highly likely that the two goals are mutually exclusive, says Suely Araújo, former Ibama president and a public policy expert at the Climate Observatory, an association of 95 socioenvironmental organizations in Brazil. Suely draws attention to another fallacious argument often advanced by government spokespersons: Brazil needs the revenue from new oil exploration frontiers to finance its energy transition. “We don’t have time for this. A block drilled today will generate oil and royalties a decade from now. We don’t have a decade to wait for the energy transition. This would put the climate crisis at an unbearable level,” says Suely.

Expectations: Chief of Staff Dilma Rousseff, Senate President José Sarney, First Lady Marisa, Lula, House Speaker Michel Temer, and Mines and Energy Minister Edison Lobão at the official announcement of pre-salt regulations, in 2009. Photo: Alan Marques/Folhapress

Recipe for disaster: Brazil plans to export pollution while sacrificing local nature

In 2022, Brazil stood ninth among the world’s oil producers, a list headed by the United States, Saudi Arabia, and Russia. It extracted an average of 3.1 million barrels per day, a volume that will rise this year. More than one-third of this output was for export.

In February 2023, Brazil’s Energy Research Office, an agency within the mines and energy ministry, released the Energy Transition Program. According to the document, oil currently accounts for 35% of the nation’s energy grid, a figure predicted to drop to 5%-15% by 2050, the year Brazil has pledged to achieve net zero greenhouse gas emissions, meaning it will not emit more than nature can absorb. Yet the program does not suggest cutting back production. Brazil, according to the document, would expand its crude output at least until 2040, to around 4.5 million bpd, “aimed at meeting foreign demand.”

Brazil’s National Energy Plan 2050, launched by the Energy Research Office under the Bolsonaro administration in 2020, goes even further. It states that Brazil should consolidate its position as a “major oil producer and exporter” by 2050. The plan forecasts output of 5.5 million bpd by 2030 and up to 6.1 million bpd by 2050. In a less favorable international scenario, production would still be at least 3.6 million bpd 27 years from now.

These projections underlie statements like the one Petrobras CEO Jean Paul Prates made October 9 in a conversation with journalists: “We are going to produce increasingly more of the oil that humanity will consume.” Or that of Cristiano Pinto da Costa, CEO of British Shell Brazil, who in February told the news daily O Estado de S. Paulo that Brazil’s oil fields will be among the last his company shuts down. Or that of Mines and Energy Minister Alexandre Silveira, who in late September told the Financial Times that Brazil has the “moral authority” to talk to the world about a “just energy transition” while at the same time boosting its oil output, including its search for oil in the Foz do Amazonas basin.

Silveira argues that Brazil is in this favorable position because more than 80% of the country’s electrical grid is based on non-fossil fuels, a much fatter share than the world average of less than 30%. But over 50% of Brazil’s entire energy grid—including transportation and industrial and household fuel—is fed by fossil fuels. Although this percentage is still below the world average of 85%, the energy sector is responsible for 18% of greenhouse gas emissions in Brazil, which is the world’s seventh-largest emitter. If it is a given that deforestation must be stopped, since it is the culprit behind most of Brazil’s emissions, it is equally true that unless the country reshapes its energy grid, it cannot reach net zero by 2050.

Likewise at the end of September, the International Energy Agency (IEA) released its second report in two years, outlining what needs to be done for the world to reach net zero by 2050. According to the document, there is still time to limit the planet’s average temperature rise to 1.5°C over pre-Industrial levels by the end of this century, the pledge countries made when they signed the Paris Climate Accord in 2015. But it will be a race: world oil demand must fall by 75%, from 97 million bpd in 2022 to 77 million bpd in 2030 and 24 million bpd in 2050.

At the launch of the report, the executive director of the IEA, Turkish economist Fatih Birol, predicted that oil demand will peak before 2030. He said he was encouraged by increased reliance on wind and solar power and growing electric car sales and reiterated the position of the previous report, released in 2021, that there is no need to open any new fossil fuel exploration frontiers. According to Birol, oil and gas companies must think carefully, because large-scale investments in fossil fuels pose not only a risk to our climate but also, given demand trends, an economic and business risk.

In early September, the United Nations Convention on Climate Change published the first technical evaluation of the measures adopted by signatories of the Paris agreement. The document shows that in 2019 and 2020, more was invested in fossil fuels than in actions aimed at tackling the climate crisis, including the production of renewables that use sources such as water, sun, wind, and biomass (i.e., organic matter sourced from crops or their residues, like sugarcane, eucalyptus, plant oils, bagasse, and garbage). In early November, the UN calculated that by 2030 world oil production would be double that amount that would be consistent with the goal of holding global heating to 1.5°C.

Petrostate: Dubai, an emirate that built its skyscrapers with oil money, will host COP28, whose main challenge will be to end fossil fuel use. Photo: Karim Sahib/AFP

Fossil fuel producers: “architects of collective devastation”

At this year’s UN Climate Change Conference, COP28, the central demand of movements fighting to save the planet will be phase-out, that is, a gradual reduction in dependence on fossil fuels. The meeting is slated to begin on November 30 in Dubai, in the United Arab Emirates, an OPEC member, under the leadership of Sultan al-Jaber, head of the local national oil company. So far, conference negotiations have failed to advance beyond the 2021 commitment to “phase down,” and then only in the case of coal.

In an interview with the Global Gas & Oil Network, made up of socioenvironmental organizations that monitor fossil fuel production, Catherine Abreu, a Canadian at the helm of the NGO Destination Zero, said that “2023 is a make-or-break year for the credibility of UN climate talks.” She stated that “history will condemn” big fossil fuel producers who insist on the “limitless expansion” of their projects: “We can now plainly see the architects of our collective devastation.”

For these architects of devastation, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was a relief. Dependent on Russian gas, which was responsible for 35% of their consumption, European countries rushed to sign new supply contracts with Arab and African countries and also delayed replacing coal. The Conservative government in Britain gave the go-ahead for exploration of a mega-field in the North Sea. In the United States, the Democratic Biden administration authorized the opening of a new exploration frontier in Alaska. Vladimir Putin’s Russia skirted oil sanctions by upping exports to countries like India and China.

Race to devastation: when Ukraine was invaded by Russia, a major gas and oil producer, prices rose, and countries sought out new fossil fuel reserves and suppliers. Photo: Anatoly Stepanov/AFP

The energy transition has ceded its place on center stage to so-called energy security. This is why Birol, from the IEA, said “Governments need to separate climate from geopolitics, given the scale of the challenge at hand.”

In addition to its two reports on the road map to climate neutrality, the agency publishes an annual World Energy Outlook, based on the policies actually adopted by countries. In the 2022 document, Brazil is on the list of those expected to expand oil production at least until 2040, along with the United States, Canada, Guyana, Venezuela, and all Arab nations—Iraq, Iran, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and the Arab Emirates. The 2023 World Energy Outlook states that in Latin America, Brazil and Guyana are the countries planning the largest hikes in oil output for export through 2035. The document warns that this will make these two nations “highly sensitive to the pace of global transitions,” that is, if the world does indeed reduce its demand for fossil fuels, there may be no one to buy the oil.

In the October 9 press interview, SUMAÚMA asked Petrobras CEO Jean Paul Prates about the IEA report. He said he finds it “very difficult to believe” that the world energy transition will happen within 30 years.

Prates argued that Petrobras’s production chain is one of the least carbon-intensive in the world. He cited the company’s technologies for reinjecting into the ground carbon dioxide released during extraction. Although environmentalists recognize that Brazil’s state-owned oil major has cut production emissions by 39% since 2015, they say that the most decisive factor is what is emitted in the daily use of fossil fuels. An analysis by the Climate Observatory showed that 85% of the carbon generated by Petrobras comes from the consumption—and not the production—of its oil and gas.

Investing in technologies that capture carbon and keep it from reaching the atmosphere has been a strategy deployed by polluting industries in response to pressure on them. But the latest IEA report suggests these technologies do not contribute much to fulfillment of Paris Accord commitments, since the carbon that is thus prevented from entering the atmosphere represents only 0.1% of annual emissions by the energy sector today.

Wishful thinking: Petrobras CEO Jean Paul Prates told SUMAÚMA that he finds it “very difficult to believe” the world energy transition will happen in 30 years. Photo: Mauro Pimentel/AFP

SUMAÚMA asked Prates if he thought competing oil companies would make room for Petrobras in a declining international market. The CEO replied, “That’s not the point.” “Many of them are going to transition or they’ll fail, because they’re going to transform themselves into something else faster than state-owned companies will. The role of state oil companies will be to shoulder this last need,” he said. Pontes also claimed that, for Brazilian society, it is better for Petrobras to “produce the last drop we need” than let other companies occupy this space in the country. Petrobras accounts for around 70% of the oil pumped in Brazil, but other enterprises have been operating in the sector since the state monopoly was broken during former president Fernando Henrique Cardoso’s first term of office (1995-1998).

Asked if he intended to revise the scenarios that project increased oil and gas production beyond 2030, Mines and Energy Minister Alexandre Silveira replied through his press office that these forecasts “are constantly revised.” However, he cited only two situational factors as the basis for revisions—“the discovery of new reserves” and “investments in the development of existing fields”—and made no mention of the IEA estimate that world demand will fall from 2030 onwards.

Roberto Schaeffer, professor of energy economics at COPPE, the graduate engineering school at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, is one of the authors of the Energy Transition Program released in February. Schaeffer supports the position that Brazilian oil, particularly its pre-salt, “could replace oils with higher production costs, larger carbon footprints, and higher refining costs.” The problem is that, for this replacement to correspond to the necessary reduction in fossil fuel consumption, there would have to be an international phase-out agreement. “It makes sense to abandon fields in Canada, Venezuela, and the United States and possibly stimulate oil such as Brazilian and Angolan,” he said.

Not, however, at the mouth of the Amazon. Schaeffer says that insisting on this new exploration front is “shooting ourselves in the foot.” “The mouth of the Amazon must be preserved, given the risks drilling would present. Defending exploration there negates the advantages Brazilian oil has in relation to other oils,” he said.

Schaeffer works with a 20- to 30-year horizon for the end of the oil age. “Our studies have shown that production and demand will fall, almost to zero, by 2050, 2060,” he said. “The war in Ukraine confused things a bit, but it’s the beginning of the end,” he went on. “If I were the CEO of Petrobras, seeing that in 20, 30 years this business will be a bad deal, I’d be very concerned about getting the company ready for a new moment.”

Ricardo Baitelo, project manager for the Brazilian non-profit Energy and Environment Institute, feels that Petrobras and advocates of fossil fuel exploration in Brazil are “overly optimistic” in counting on a significant share of an international oil market that is tending to shrink. He cites the case of China, presently the biggest emitter of greenhouse gases, which now expects to reach peak oil consumption before 2030. Amid tensions with the United States, China—Brazil’s top oil customer—wants to decrease its dependence on imported fuel.

The expectation that Brazil can rely on oil revenue indefinitely tends to postpone transition plans, Baitelo concluded, which is ultimately bad for the climate, for Brazil, and for Petrobras.

Oil for export: Bailique Archipelago, in Amapá state, a biodiverse region near the mouth of the Amazon, where the Lula administration wants to open a new exploration front. Phot: Victor Moriyama/Greenpeace

Dangerous path: Brazil might trade one oil dependency for another

During his first two terms of office (2003-2006 and 2007-2010), Lula was photographed at least three times with his hands covered in what was then called “black gold.” Nobody in Brazil missed the fact that he was mimicking the gesture made by nationalist president Getúlio Vargas in 1952, the year before Brazil passed the law that created Petrobras and gave the state-owned company a monopoly on oil exploration, production, and refining.

Led by nationalist students and members of the military, “the oil is ours” campaign was launched in 1948. At the time, Brazil had only discovered a marketable volume of petroleum in onshore wells in Bahia. But major finds in neighboring countries, like Venezuela and Argentina, fueled the belief that Brazil might also hold abundant deposits.

Getúlio Vargas gets booted: a poster from the “Oil is ours” campaign, launched in 1948 by students

and members of the military who feared dependence on foreign oil. Photo: Reproduction

Petroleum is formed from the remains of animals and plants deposited millions of years ago at the bottom of lakes and seas. Flammable and insoluble in water, oil has been used since ancient times to light homes and caulk buildings. In general, only the oil that managed to seep to the surface was used, until the mid-18th century, when the Industrial Revolution changed this equation. With the arrival of the steam engine, first coal and then other fossil fuels were used to power machines and means of transportation.

Petroleum and power: oil field in 1923 in the U.S., the world’s biggest oil producer until the 1970s. Photo: Jacques Boyer/AFP

In the early 20th century, the United States established itself as the world’s largest oil producer, a title it maintained until the 1970s and then recouped again in 2018, when it began fracking, that is, extracting gas and oil from shale by mixing water, sand, and chemical products to break rock open. During World War I, U.S. fuel supplies to France and the United Kingdom played a vital role in ensuring Germany’s defeat and earning the United States its place as a superpower. Helen Thompson, professor of political economics at the University of Cambridge in England, sees this as the dawn of the “oil age.” “It became clear that 20th-century military power would be based on oil as an energy source,” she told the Latin American journal Nueva Sociedad.

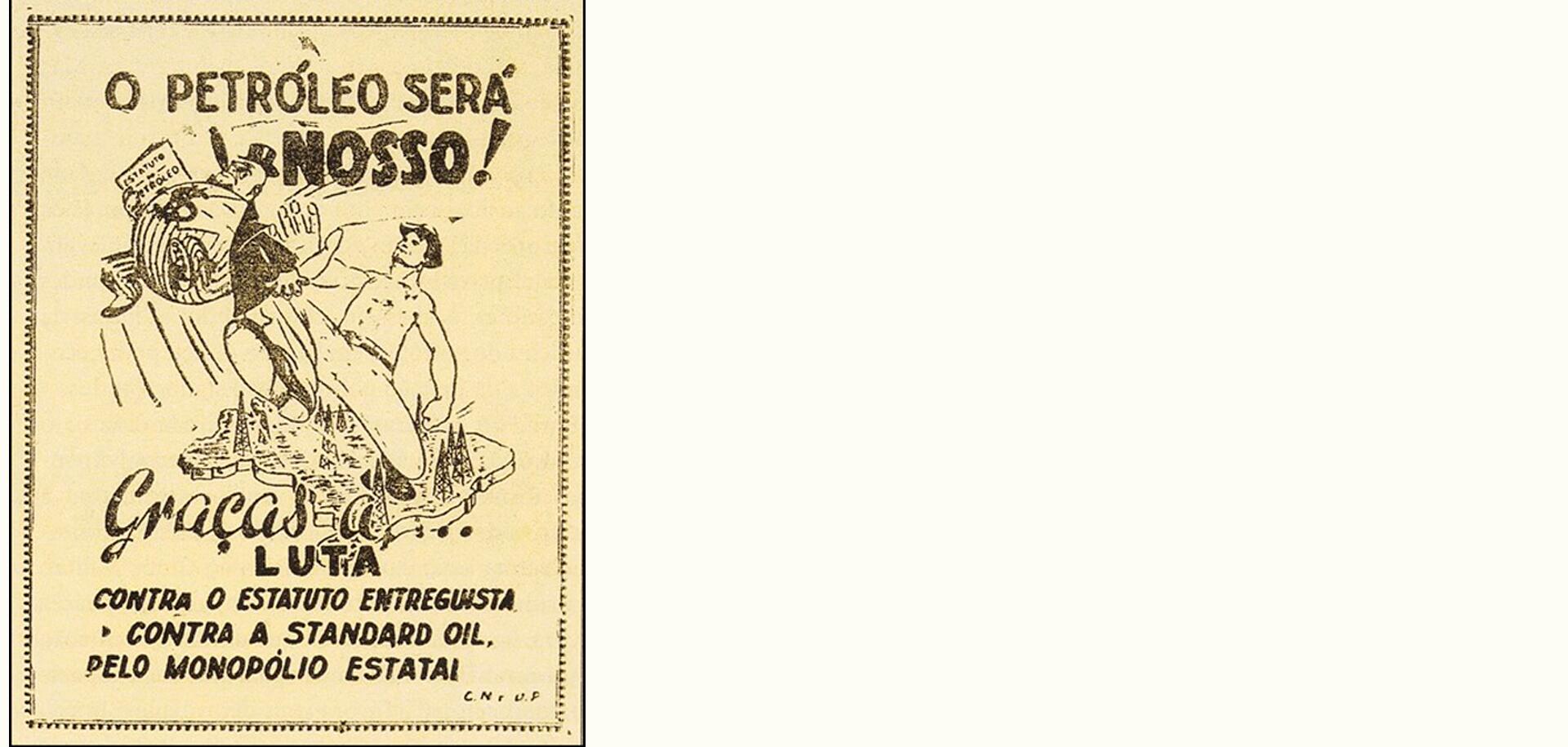

No oil, but motorized: former President Juscelino Kubitschek (1956-1961) encouraged highways and the automotive industry when Brazil was dependent on imported fuel. Photos: Folhapress

Brazil, however, waited more than 20 years after the creation of Petrobras to locate substantial reserves, found by offshore drilling along the southeast coast. During this period, the country’s dependence on imported oil did not keep it from deepening its commitment to road transportation, Brazil’s biggest fossil fuel guzzler. It was only with the discovery of its pre-salt oil that Brazilian output climbed from two million bpd in 2010 to today’s three million bpd.

Aposta na poluição: exploração de petróleo e gás de xisto por fraturamento hidráulico em 2014, na Califórnia, nos Estados Unidos. O país voltou a ser o maior produtor mundial em 2018. Foto: David McNew/AFP

Today, oil exports figure big in the Brazilian economy. In 2022, crude exports earned $42.5 billion, topped only by $46.5 billion in soybean sales abroad. From a purely economic standpoint, the problem is price instability, as always the case with raw materials. In the net zero scenario projected by the IEA, a barrel of oil is expected to plunge from today’s price of $90 to $42 by 2030 and $25 by 2050.

The curse of dependence: Oil residue on the shores of Lake Maracaibo, in Venezuela, the only Latin American nation among founding members of OPEC. Photo: Federico Parra/AFP

The Anthropocene: how the elites have used denialism to force the poor to foot the climate bill

There is no doubt the oil age has left a massive climate debt. The Global Carbon Budget, an international scientific project, calculates that the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere climbed from 277 parts per million (ppm) in the mid-18th century to 417 ppm by 2022, a rise of 50%. From 2012 to 2021, worldwide fossil fuel use emitted an average of 35 billion metric tons of carbon each year while land-use change, like deforestation, produced five billion metric tons. The air would be even more polluted if forests and oceans did not absorb around half of what is emitted—but today this absorption rate is trending downward due to the predatory exploitation of nature.

The study released in September by the UN Convention on Climate Change shows that between 2011 and 2020, the average temperature of the planet was already 1.1°C higher than in the pre-Industrial era. The measures announced by countries so far are not enough to hold this rise to 1.5°C. Instead, these measures are predicted to lead to an increase of 2.4°C to 2.6°C by the end of the century.

Since the advent of the 21st century, scientists and philosophers have been debating whether the oil age and its inextricable connection with the expansion of capitalism and today’s predominant notion of progress has already altered the planet so much that it has generated a new geological period: the Anthropocene. With “anthropos”—Greek for “humans”—at the center, this new epoch is the result of the endless harnessing of nature in the name of a development model based on intensive consumption. During the Holocene—which means “totally new,” although the epoch began 12,000 years ago, at the end of the last Ice Age—a stable climate allowed agriculture to flourish and people to settle in towns. During the Anthropocene, these scholars argue, human activities have determined how nature functions. Several interlinked phenomena—the heating of the Earth, the pollution of rivers and seas, the loss of biodiversity—are threatening life in our shared house.

The French philosopher Bruno Latour (1947-2022) said we are living in a “new climatic regime.” To avert destruction, it is not enough to remove carbon from the atmosphere; we must “change our conditions of existence” and leave behind modernity as understood during the 1970s, Latour said in an interview with Folha de S.Paulo in 2020.

The challenge to securing a political consensus about what needs to be done stems from the scale of the changes necessary to prevent the extinction of life.

In an essay for the book The Great Regression, published in England in 2017 by Polity Press, Latour reflects on the election of Donald Trump the previous year and introduces the idea of what he calls “plausible fiction.” In the late 1990s, he argues, the “enlightened elites” realized the mounting peril of climate change and the chances of having to “pay dearly” for this. But many decided someone else should foot the bill—and denialism became their tool to this end.

“If this hypothesis is correct, it enables us to grasp what, from the 1980s, was called ‘deregulation’ and the ‘dismantling of the Welfare State,’ from the 2000s, ‘climate change denial,’ and above all, over the last forty years, a dizzying increase in inequality,” the philosopher wrote. “And we need to see that all of these things are part of the same phenomenon: the elites were so thoroughly enlightened that they decided there would be no future life for the world, so they needed to get rid of all the burdens of solidarity as fast as possible (i.e. deregulation); that they needed to construct a kind of golden fortress for the few per cent of people who would manage to get on in life (i.e. soaring inequality); and that, to hide the crass selfishness of this flight from the common world, they would need to completely deny the very existence of the threat behind this mad dash (climate change denial).”

Ideas like Latour’s have gained such traction that the expression “just transition” is now on many people’s lips, albeit with different emphases and even meanings. A discussion is emerging about taxing the carbon emitted by fossil fuels as a way of putting pressure on companies. African countries have proposed a global system of taxes on the trade of fossil fuels, maritime transportation, and aviation, with proceeds financing “large-scale” actions to address the climate crisis.

The political scientist Breno Bringel, a professor with the Institute of Social and Political Studies at Rio de Janeiro State University, is part of a network of academics and activists who are analyzing what they term the “socio-ecological transition” from the standpoint of populations in the Global South. Bringel, who is a member of the Ecosocial and Intercultural Pact of the South, is one of the formulators of the concept “decarbonization consensus.” This concept, which he and the Argentinian sociologist Maristella Svampa introduced in an article in the journal Nueva Sociedad, warns about the risks of a transition based solely on changes to the energy grid.

Dangerous decision: Brazilian oil consumption is expected to drop steadily but the country plans to sell to the global market, which needs to shrink. The image shows a floating production vessel in Guanabara Bay, Rio de Janeiro. Photo: Tânia Rêgo/Agência Brasil

Despite its green face, the “decarbonization consensus” threatens to usher in a new extractivist phase, creating “zones of sacrifice” in countries of the South and even regions of the North, according to the two scholars. “This consensus does not take into account all the dimensions of the ecological transition, which must necessarily involve the food system, the organization of cities, changes in consumption patterns,” warns Bringel. “It is an idea spun around rhetoric about innovation and technology, as if, once again, capitalism and society could control nature.”

Bringel recently met with organizations from the European Union, which is interested in securing raw materials and renewable fuel suppliers, including the much hyped “green hydrogen”—gas obtained by using non-fossil fuel sources such as wind or sun to split water molecules, or H²O, formed of two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen. “Basically, the big issue for central countries is energy security. [But] for countries of the South, it’s the possibility of new forms of financing,” the political scientist said. “Brazil is being projected as a new niche market for the sale of renewable technologies at prices that are feasible for the Global North.”

“Green” extractivism: Indigenous people protesting lithium mining encounter repression in Jujuy province, Argentina, in 2023. The mineral is used in making batteries. Photo: Edgardo A. Valera/Telam/AFP

Future: if Brazil wants to guarantee oil profits “to the last drop,” there may be no tomorrow

In the video celebrating Petrobras’s 70th anniversary, Lula said the corporation is “more than an oil and gas concern.” “This mega-opportunity that this country has, to be the world’s largest center of attraction for renewable energy production, will depend on the efforts of our prized Petrobras,” the president said. “Even when the oil runs out, Petrobras will still be the country’s great energy company.”

How this will be accomplished doesn’t seem clear for either the state-run company or the government.

Petrobras remains the largest corporation in Brazil and ranks among the ten largest oil concerns in the world. Yet even its defenders recognize that the company lost much of the symbolic capital it once had, both because of the corruption allegations made during the Operation Car Wash investigation and because of what has been called the dismantling of the company under the administrations of Bolsonaro and Temer (2016-2018). The state-owned enterprise sold off dozens of assets, including refineries, and was left to concentrate on oil exploration.

In the company’s strategic plan approved in 2022, only 6% of investments for the subsequent four years—the equivalent of $4.4 billion—would be earmarked for “low-carbon initiatives.” The plan has now been revised, and the new one, for 2024-2028, reserves 11% for “low-carbon” projects. The figure is lower than the maximum of 15% mentioned earlier by Prates—and than the average for Europe’s main oil companies today.

Under the strategic plan released on November 23, total investments stand at $102 billion, 31% more than in the previous plan. More money will be slated for refineries, but the bulk—72%—will still go to oil and gas exploration and production. Of the $11.5 billion that Petrobras plans to allocate to “low carbon,” $7 billion will in practice go to non-fossil energies such as wind, solar, and biofuels—in other words, less than 7% of the company’s total projected investments, and even then, this will be in “maturing” projects. The rest of the money will be for research and, above all, the “decarbonization” of oil operations.

In the days leading up to approval of the new plan by the Petrobras Board of Directors, much pressure was felt from Mines and Energy Minister Alexandre da Silveira and especially from the financial market, which was wary that the state company might start generating lower profits in the short term.

The controversy over the strategic plan reflected the fact that Petrobras is a company “in dispute,” in the words of Mahatma dos Santos, technical director of Ineep, the oil research institute at the Brazilian oil workers’ trade union, whom I interviewed in late September. “It’s such a strategic company from the standpoint of regional and global energy security that it’s always in dispute,” Mahatma said. “Workers are one of the actors, the market is another. The internal dynamics of governance and of national and international politics define Petrobras’s business guidelines,” he added. Private shareholders, most of them foreign, hold 49.74% of the voting shares and 81.51% of the non-voting shares in the state-owned company.

Possible alternative: Petrobras is considering the production of wind power offshore. The image shows wind turbines in Rio Grande do Norte state. Photo: Yasuyoshi Chiba/AFP

The defining question of our lives: If “the oil is ours,” do we want it?

Roberto Schaeffer, from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, and Ricardo Baitelo, from the NGO Energy and Environment Institute, maintain that Brazil needs to define some energy transition policies soon or it will be left playing catchup with decisions taken by the United States, Europe, and China. They argue that this will help Petrobras determine what new energies to invest in. “To phase out, governments and businesses must replace fossil fuel revenue with another source, and today’s renewable revenue still isn’t enough,” said Baitelo.

It is not clear, for example, whether the government will offer any incentives for electric cars or the production of green hydrogen for domestic use and not just export. In the area of transportation, Brazil’s expertise lies in biomass fuels such as ethanol. The administration has sent Congress a bill on “fuels of the future,” with a focus on biofuels. In the meantime, the European Union is keen on hydrogen as a marine and aviation fuel while the automotive industry, which is global, is putting money into electric cars. Brazil may eventually find its choices do not mesh well with its trade partners’.

Direto para a China: projeto de lítio Grota do Cirilo, da empresa canadense Sigma Lithium, em Minas Gerais, que está destinando sua produção para os chineses. Foto: Douglas Magno/AFP

If Brazil continues to fall behind in the planning and execution of its energy transition, the country may ultimately end up hostage to a new geopolitics of energy as cruel as that of the oil age. Solar energy, for example, already accounts for 5.3% of the capacity of the national electrical grid, but the vast majority of solar panels come from China. Foreign companies are now rushing to Brazil to source so-called critical minerals like lithium, cobalt, nickel, iridium, and platinum, used in batteries and electrolyzers, the equipment that splits water molecules to obtain green hydrogen.

This whole debate about what can be done to replace oil revenue and open new fronts for the development of the industry takes place mainly in the sphere of the market. In the context, in fact, of what Breno Bringel and Maristella Svampa call the “decarbonization consensus.”

The Ecosocial and Intercultural Pact of the South drafted an ecological transition plan for Colombia, but Bringel said it cannot be applied to other countries because everything depends on each local reality, including material conditions and community experiences and struggles, such as the referendum in Ecuador this past August that banned oil production in Yasuní Park, in the Amazon. For Bringel, an alternative agenda has to rethink the 20th-century principles of the left. “The left got stuck on the idea of equality, justice, and social redistribution as the three great principles that are fundamental,” he said. “But we have to add the principles of care, interdependence between humans and nature, reparations for the climate debt, and ethics among species.”

It’s ours but we don’t want it: people’s march at the Amazon Summit in August 2023 calls for an end to oil drilling in the planet’s largest rainforest. Photo: João Paulo Guimarães/Greenpeace

In the climate emergency, no one is an island—islands, in fact, are the first to vanish as sea levels rise. Most people will have to face a dilemma: change or perish. If history has left any clues, there is a considerable risk that this will all culminate in war and massacre.

Avoiding this dystopian end will require a political struggle as great as our fear that life may be extinguished. The fight will necessarily entail the mobilization of Indigenous and traditional populations to guarantee their permanence in the forests and biomes that they conserve and of which they are a part, the organization of people living in poor, outlying urban areas, who spend hours on packed buses to get to work, the struggle of those who defend the social function of land, and the ability of activists to shake the structures of the world built by oil money. This is everyone’s battle—and it is time to declare: if the oil is ours, we have the right to say we don’t want it.

Report and text: Claudia Antunes

Fact check: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquiria Della Pozza

Spanish translation: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Diane Whitty

Visual editing: Lela Beltrão

Editorial workflow, copy editing, and layout: Viviane Zandonadi

Direction: Eliane Brum